Vincentiana Vol. 48, No. 1 [Full Issue]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kirche Und Schule in Äthiopien

Kirche und Schule in Äthiopien Mitteilungen der Tabor Society e.V. Heidelberg ISSN 1615-3197 Heft 64 / November 2011 Kirche und Schule in Äthiopien, Heft 64 / November 2011 IMPRESSUM KIRCHE UND SCHULE IN ÄTHIOPIEN (KuS) - Mitteilungen der TABOR SOCIETY - Deutsche Gesellschaft zur Förderung orthodoxer Kirchenschulen in Äthiopien e.V. Heidelberg Dieses Mitteilungsblatt ist als Manuskript gedruckt Vorstandsmitglieder der Tabor Society: und für die Freunde und Förderer der Tabor Society bestimmt. 1. Vorsitzender: Pfr. em. Jan-Gerd Beinke Die Tabor Society wurde am 22. März 1976 beim Furtwängler-Str. 15 Amtsgericht Heidelberg unter der Nr. 929 ins 79104 Heidelberg Vereinsregister eingetragen. Das Finanzamt Heidel- Tel.: 0761 - 29281440 berg hat am 21. 07. 2011 unter dem Aktenzeichen 32489/38078 der Tabor Society e.V. Heidelberg den Stellvertr. Vorsitzende und Schriftführerin: Freistellungsbescheid zur Körperschaftssteuer und Dr. Verena Böll Gewerbesteuer für die Kalenderjahre 2005, 2006, Alaunstr. Str. 53 2007 zugestellt. 01099 Dresden Tel.: 0351- 8014606 Darin wird festgestellt, dass die Körperschaft Tabor Society e.V. nach § 5 Abs.1 Nr.9 KStG von der Kör- Schatzmeisterin: perschaftssteuer und nach § 3 Nr. 6 GewStG von der Dorothea Georgieff Gewerbesteuer befreit ist, weil sie ausschließlich und Im Steuergewann 2 unmittelbar steuerbegünstigten gemeinnützigen Zwek- 68723 Oftersheim ken im Sinne der §§ 51 ff. AO dient. Die Körperschaft Tel.: + Fax: 06202 - 55052 fördert, als allgemein besonders förderungswürdig an- weitere Vorstandsmitglieder erkannten gemeinnützigen Zweck, die Jugendhilfe. Dr. Kai Beermann Die Körperschaft ist berechtigt, für Spenden und Mit- Steeler Str. 402 gliedsbeiträge, die ihr zur Verwendung für diese 45138 Essen Zwecke zugewendet werden, Zuwendungs- bestäti- Tel.: 0201 - 265746 gungen nach amtlich vorgeschriebenem Vordruck (§ 50 Abs. -

The Dialogue Between Religion and Science in Today's World from The

International Journal of Orthodox Theology 8:3 (2017) 203 urn:nbn:de:0276-2017-3075 Gavril Trifa The Dialogue between Religion and Science in Today’s World from the View of Orthodox Spirituality Abstract One of the core issues of today’s world, the dialogue between science and religion has recently come to the attention of new fields of knowledge, which points to a change in some of the “classical” elements. Having a different history in the East and the West, in Catholic and Orthodox Christianity, the relation between faith and science has lived through some problematic centuries, marked by the attempt of some scientific domains to prove the universe’s materialist ontology and thus the uselessness of religion. This paper aims to present an overview of the Rev. Assist. Prof. Ph.D. stages that marked the often radical Gavril Trifa, Faculty of separation of science from religion, by Orthodox Theology of the highlighting the mutations recorded West University of Timi- during the past few decades not only şoara, Romania 204 Gavril Trifa in society but also in the lives of the young, as a result of the unprecedented development of technology. With technology failing to raise both communication and interpersonal communication to the anticipated level, recent research does not hesitate in emphasizing the unfavourable consequences bring about by the development of the means of communication, regarding the human being’s relation to oneself and one’s neighbours. The solutions we have identified enable an update of the patristic model concerning the relation between religion and science, in the spirit of humility, the one that can bring the Light of life. -

Mary in the Doctrine of Berulle on the Mysteries of Christ Vincent R

Marian Studies Volume 36 Proceedings of the Thirty-Sixth National Convention of The Mariological Society of America Article 11 held in Dayton, Ohio 1985 Mary in the Doctrine of Berulle on the Mysteries of Christ Vincent R. Vasey Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Vasey, Vincent R. (1985) "Mary in the Doctrine of Berulle on the Mysteries of Christ," Marian Studies: Vol. 36, Article 11. Available at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies/vol36/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Publications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Studies by an authorized editor of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Vasey: Mary in the Doctrine of Berulle MARY IN THE DOCTRINE OF BERULLE ON THE MYSTERIES OF CHRIST Two monuments Berulle left the Church, aere perennina: more enduring than bronze, are his writings and his Congrega tion of the Oratory. He took part in the great controversies of his time, religious and political, but his figure takes its greatest lus ter with the passing of years because of his spiritual work and the influence he exerts in the Church by those endued with his teaching. From his integrated life originated both his works and his institution; that is why both his writings and the Oratory are intimately connected. His writings in their final synthesis-and we are concerned above all with the culmination of his contem plation and study-center about Christ, and his restoration of the priesthood centers about Christ. -

St Justin De Jacobis: Founder of the New Catholic Generation and Formator of Its Native Clergy in the Catholic Church of Eritrea and Ethiopia

Vincentiana Volume 44 Number 6 Vol. 44, No. 6 Article 6 11-2000 St Justin de Jacobis: Founder of the New Catholic Generation and Formator of its Native Clergy in the Catholic Church of Eritrea and Ethiopia Abba lyob Ghebresellasie C.M. Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Ghebresellasie, Abba lyob C.M. (2000) "St Justin de Jacobis: Founder of the New Catholic Generation and Formator of its Native Clergy in the Catholic Church of Eritrea and Ethiopia," Vincentiana: Vol. 44 : No. 6 , Article 6. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana/vol44/iss6/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. St Justin de Jacobis: Founder of the New Catholic Generation and Formator of its Native Clergy in the Catholic Church of Eritrea and Ethiopia by Abba lyob Ghebresellasie, C.M. Province of Eritrea Introduction Biblical References to the Introduction of Christianity in the Two Countries While historians and archeologists still search for hard evidence of early Christian settlements near the western shore of the Red Sea, it is not difficult to find biblical references to the arrival of Christianity in our area. And behold an Ethiopian, eunuch, a minister of Candace, queen of Ethiopia, who was in charge of all her treasurers, had come to Jerusalem to worship... -

General Curia

VINCENTIANA 6-2005 - FRANCESE November 23, 2005 − 1ª BOZZA .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ENERAL..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................URIA.............................................. ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Mémoire HDR H. Pennec2019

Historiographie, productions de savoirs missionnaires, terrains, archéologie. Éthiopie XVIe-XXIe siècle Mémoire de recherche inédit présenté en vue de l’habilitation à diriger des recherches par Hervé PENNEC Chargé de recherches au CNRS – section 33 (Institut des mondes aFricains – IMAF/UMR 8171 – CNRS & 243 IRD) Composition du jury : Pierre-Antoine Fabre, Directeur d’Etudes – EHESS (garant) Marie-Laure Derat, Directrice de recherches – CNRS (rapporteure) Henri Médard, Professeur d’histoire à l’Aix-Marseille Université (rapporteur) Antonella Romano, Directrice d’Etudes – EHESS Angelo Torre, Professeur d’histoire à l’Università degli Studi del Piemonte Orientale Date de soutenance : le 8 juin 2019 à l’Ecole des Hautes Etudes en sciences sociales Hervé Pennec Historiographie, productions de savoirs missionnaires, terrains, archéologie. Éthiopie XVIe-XXIe siècle Vol. 2 : Mémoire de recherche inédit présenté en vue de l’habilitation à diriger des recherches EHESS, 2018 2 3 Introduction En février 1541, le roi éthiopien Gälawdéwos (1540-1559), identifié au « prêtre Jean », reçut des renforts militaires, destinés à son prédécesseur, Lebnä Dengel mort en septembre 1540, du roi João III (1521-1557) de Portugal. À la tête de cette armée (environ 400 soldats), se trouvait Christovão da Gama (un des fils du déjà célèbre navigateur1). Cet événement fut le point d’orgue des relations entre le Portugal et l'Éthiopie, dont les origines politiques remontaient à un demi-siècle. Sur un plan théologique, fantasmatique, elles étaient multiséculaires. La légende du prêtre Jean remonte en effet au milieu du XIIe siècle. Elle prend source dans une lettre apocryphe soi-disant adressée à l'empereur de Byzance Manuel Ier Comnène (1143-1180) et à l'empereur du Saint Empire germanique, Frédéric Ier Barberousse (1152-1190). -

Models for Our Vincentian Vocation: Causes in Process

Vincentiana Volume 48 Number 4 Vol. 48, No. 4-5 Article 17 7-2004 Models for Our Vincentian Vocation: Causes in Process Roberto D'Amico Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation D'Amico, Roberto (2004) "Models for Our Vincentian Vocation: Causes in Process," Vincentiana: Vol. 48 : No. 4 , Article 17. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana/vol48/iss4/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VINCENTIANA 4/5-2004 - INGLESE July 14, 2003 − 2a BOZZA Vincentiana, July-October 2004 Models for Our Vincentian Vocation: Causes in Process by Roberto D’Amico Postulator General 9.VII.2004 Introduction A great 20th-century philosopher, Henry Bergson, has noted that “the greatest persons in history are not the conquerors but rather the saints.” In more recent times, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger has rightly stated that “it is not the occasional majorities that are formed here and there within the Church who give direction to the Church and to our lives. The saints are the real, determined majority who give direction to our lives. We stick to them! They translate the divine into human form, the eternal into concrete time.” In a changing world, not only do the saints not remain outside it historically or culturally but they are becoming ever more credible subjects of it. -

Reading Records of Literary Authors: a Comoatisom.Of Some Publishedfaotebocks

DOCUMENT INSURE j ED41.820. CS 204 003 0 AUTHOR Murray, Robin Mark '. TITLE. Reading Records of Literary Authors: A ComOatisom.of Some Publishedfaotebocks. PUB DATE Dec 77 NOTE 118p.; N.A. thesis, The Ilniversity.of Chicago . I EDRS PRICE f'"' NF-S0.83 HC-$6.01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Authors; Bibliographies;_ Rooks; ,ocompcsiticia (Literary); *Creative Writing; *Diariei; Literature* Masters Theses; *Poets; Reading Habits; Reading Materials; *Recrtational Reading; Study Habits IDENTIFIERS Notebooks;.*Note Taking - ABSTRACT The significance ofauthore reading notes may lie not only in their mechanical function as inforna'tion storage devices providing raw materials for writing, but also in their ability to 'concentrate and to mobilize the latent ,emotional and. creative 1 resources of their keepers. This docmlent examines records of 'reading found in the published notebcols'of eight najcr_British.and United States writers of the sixteenth through twentieth. centuries. Through eonparison of their note-taking practices, the following topics are explored: how each author came to make reading notes, the,form.in which notes were' made, and the vriteiso habits of consulting; and using their notes (with special reference to distinctly literary uses). The eight writers whose notebooks ares-exaninea in dtpth are Francis Badonc John Milton, Samuel Coleridge,.Ralph V. Emerson, Henry D. Thoreau, Mark Twain, Thomas 8ardy, and Thomas Violfe.:The trends that emerge from these eight case studiesare discussed, and an extensive bibliograity of published -

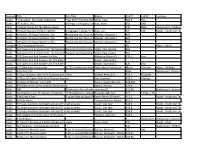

Resource Typeitle Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Location Books

Resource TitleType Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Location Books "Impossible" Marriages Redeemed They Didn't End the StoryMiller, in the MiddleLeila 265.5 MIL Books "R" Father, The 14 Ways To Respond To TheHart, Lord's Mark Prayer 242 HAR DVDs 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family JUV Bible Audiovisual - Children's Books 10 Good Reasons To Be A Catholic A Teenager's Guide To TheAuer, Church Jim. Y/T 239 Books - Youth and Teen Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Compact Discs100 Inspirational Hymns CD Music - Adult Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome 265 Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome 265 Books 101 Questions And Answers On Paul Witherup, Ronald D. 235.2 Paul Compact Discs101 Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. Books 101 Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. 220 BRO Compact Discs120 Bible Sing-Along songs & 120 Activities for Kids! Twin Sisters Productions Music Children Music - Children DVDs 13th Day, The DVD Audiovisual - Movies Books 15 days of prayer with Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton McNeil, Betty Ann 235.2 Elizabeth Books 15 Days Of Prayer With Saint Thomas Aquinas Vrai, Suzanne. -

The Cathars of Languedoc As Heretics

PROJECT DEMONSTRATING EXCELLENCE The Cathars of Languedoc as Heretics: From the Perspectives of Five Contemporary Scholars by Anne Bradford Townsend Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a concentration in Arts And Sciences and a specialization in Medieval Religious Studies July 9, 2007 Core Faculty Advisor: Robert McAndrews, Ph.D. Union Institute & University Cincinnati, Ohio UMI Number: 3311971 Copyright 2008 by Townsend, Anne Bradford All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3311971 Copyright 2008 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 E. Eisenhower Parkway PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT The purpose of this dissertation is to demonstrate that the Cathar community of Languedoc, far from being heretics as is generally thought, practiced an early form of Christianity. A few scholars have suggested this interpretation of the Cathar beliefs, but none have pursued it critically. In this paper I use two approaches. First, this study will examine the arguments of five contemporary English language scholars who have dominated the field of Cathar research in both Britain and the United States over the last thirty years, and their views have greatly influenced the study of the Cathars. -

ABSTRACT Evelyn Waugh and La Nouvelle Théologie Dan Reid

ABSTRACT Evelyn Waugh and La Nouvelle Théologie Dan Reid Makowsky, Ph.D. Mentor: Ralph C. Wood, Ph.D. This dissertation seeks to provide a more profound study of Evelyn Waugh’s relation to twentieth-century Catholic theology than has yet been attempted. In doing so, it offers a radical revision of our understanding of Waugh’s relation to the Second Vatican Coucil. Waugh’s famous contempt for the liturgical reforms of the early 1960s, his self-described “intellectual” conversion, and his identification with the Council of Trent, have all contributed to a commonplace perception of Waugh as a reactionary Catholic stridently opposed to reform. However, careful attention to Waugh’s dynamic artistic concerns and the deeply sacramental theology implicit in his later fiction reveals a striking resemblance to the most important Catholic theological reform movement of the mid-twentieth century: la nouvelle théologie. By comparing Waugh’s artistic project to the theology of the Nouvelle theologians, who advocated the recovery of a fundamentally sacramental theology, this dissertation demonstrates that the two mirror one another in many of their basic concerns. This mirroring was no mere coincidence. Waugh’s long-time mentor Father Martin D’Arcy was steeped in many of the same sacramentally-minded thinkers as the Nouvelle theologians. Through D’Arcy’s theological influence as well as the deepening of Waugh’s own faith, he, too, developed a sacramental cast of mind. In reading some of the key works of Waugh’s later years, I will show how Waugh realized this sacramental outlook in his art. Ultimately, this dissertation argues that Waugh’s main contribution to the renewal of sacramental thought within Catholicism lies in his portrayal of personal vocation as the remedy for acedia, or sloth, which he considered the “besetting sin” of the age. -

Aethiopica 15 (2012) International Journal of Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies

Aethiopica 15 (2012) International Journal of Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies ________________________________________________________________ TEDROS ABRAHA, Pontifical Oriental Institute, Rome Article The GƼ’Ƽz Version of Philo of Carpasia’s Commentary on Canticle of Can- ticles 1:2–14a: Introductory Notes Aethiopica 15 (2012), 22–52 ISSN: 2194–4024 ________________________________________________________________ Edited in the Asien-Afrika-Institut Hiob Ludolf Zentrum für Äthiopistik der Universität Hamburg Abteilung für Afrikanistik und Äthiopistik by Alessandro Bausi in cooperation with Bairu Tafla, Ulrich Braukämper, Ludwig Gerhardt, Hilke Meyer-Bahlburg and Siegbert Uhlig The GƼʞƼz Version of Philo of Carpasia߈s Commentary on Canticle of Canticles 1:2߃14a: Introductory Notes TEDROS ABRAHA, Pontifical Oriental Institute, Rome Premise The fragment with Philo of Carpasia߈s explanation of Canticle of Canticles 2߃14a bears the title ҧџՅю֓ ѢрѐӇ TƼrgwame SÃlomon ߋInterpretation :1 of Salomonߌ. In his shelf list of the Ethiopian manuscripts kept at the Ethi- opian archbishopric in Jerusalem,1 Ephraim Isaac makes the following re- marks in relation to the manuscript JE300E (MS 119 at the Ethiopian arch- bishopric in Jerusalem): This is the title given to the work which contains, beside other compo- site monastic works, a commentary to Song of Songs 1: 2߃14a (fols. 3a߃ 20a). This commentary is the work of Philo of Carpasia (Philon Philgos) (c. 400). I thank Prof. Sebastian Brock who helped to identify this work with the help of Rev. Roger Cowley.2 The commentary in- corporated into the catena of Procopius is published in PG KL. (In Lat- in, see Epiphanius of Salamis). As far as I know this is the only known Ms of this work in Geʞez.