The Dialogue Between Religion and Science in Today's World from The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mary in the Doctrine of Berulle on the Mysteries of Christ Vincent R

Marian Studies Volume 36 Proceedings of the Thirty-Sixth National Convention of The Mariological Society of America Article 11 held in Dayton, Ohio 1985 Mary in the Doctrine of Berulle on the Mysteries of Christ Vincent R. Vasey Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Vasey, Vincent R. (1985) "Mary in the Doctrine of Berulle on the Mysteries of Christ," Marian Studies: Vol. 36, Article 11. Available at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies/vol36/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Publications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Studies by an authorized editor of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Vasey: Mary in the Doctrine of Berulle MARY IN THE DOCTRINE OF BERULLE ON THE MYSTERIES OF CHRIST Two monuments Berulle left the Church, aere perennina: more enduring than bronze, are his writings and his Congrega tion of the Oratory. He took part in the great controversies of his time, religious and political, but his figure takes its greatest lus ter with the passing of years because of his spiritual work and the influence he exerts in the Church by those endued with his teaching. From his integrated life originated both his works and his institution; that is why both his writings and the Oratory are intimately connected. His writings in their final synthesis-and we are concerned above all with the culmination of his contem plation and study-center about Christ, and his restoration of the priesthood centers about Christ. -

Reading Records of Literary Authors: a Comoatisom.Of Some Publishedfaotebocks

DOCUMENT INSURE j ED41.820. CS 204 003 0 AUTHOR Murray, Robin Mark '. TITLE. Reading Records of Literary Authors: A ComOatisom.of Some Publishedfaotebocks. PUB DATE Dec 77 NOTE 118p.; N.A. thesis, The Ilniversity.of Chicago . I EDRS PRICE f'"' NF-S0.83 HC-$6.01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Authors; Bibliographies;_ Rooks; ,ocompcsiticia (Literary); *Creative Writing; *Diariei; Literature* Masters Theses; *Poets; Reading Habits; Reading Materials; *Recrtational Reading; Study Habits IDENTIFIERS Notebooks;.*Note Taking - ABSTRACT The significance ofauthore reading notes may lie not only in their mechanical function as inforna'tion storage devices providing raw materials for writing, but also in their ability to 'concentrate and to mobilize the latent ,emotional and. creative 1 resources of their keepers. This docmlent examines records of 'reading found in the published notebcols'of eight najcr_British.and United States writers of the sixteenth through twentieth. centuries. Through eonparison of their note-taking practices, the following topics are explored: how each author came to make reading notes, the,form.in which notes were' made, and the vriteiso habits of consulting; and using their notes (with special reference to distinctly literary uses). The eight writers whose notebooks ares-exaninea in dtpth are Francis Badonc John Milton, Samuel Coleridge,.Ralph V. Emerson, Henry D. Thoreau, Mark Twain, Thomas 8ardy, and Thomas Violfe.:The trends that emerge from these eight case studiesare discussed, and an extensive bibliograity of published -

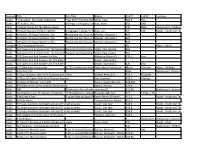

Resource Typeitle Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Location Books

Resource TitleType Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Location Books "Impossible" Marriages Redeemed They Didn't End the StoryMiller, in the MiddleLeila 265.5 MIL Books "R" Father, The 14 Ways To Respond To TheHart, Lord's Mark Prayer 242 HAR DVDs 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family JUV Bible Audiovisual - Children's Books 10 Good Reasons To Be A Catholic A Teenager's Guide To TheAuer, Church Jim. Y/T 239 Books - Youth and Teen Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Compact Discs100 Inspirational Hymns CD Music - Adult Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome 265 Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome 265 Books 101 Questions And Answers On Paul Witherup, Ronald D. 235.2 Paul Compact Discs101 Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. Books 101 Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. 220 BRO Compact Discs120 Bible Sing-Along songs & 120 Activities for Kids! Twin Sisters Productions Music Children Music - Children DVDs 13th Day, The DVD Audiovisual - Movies Books 15 days of prayer with Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton McNeil, Betty Ann 235.2 Elizabeth Books 15 Days Of Prayer With Saint Thomas Aquinas Vrai, Suzanne. -

The Cathars of Languedoc As Heretics

PROJECT DEMONSTRATING EXCELLENCE The Cathars of Languedoc as Heretics: From the Perspectives of Five Contemporary Scholars by Anne Bradford Townsend Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a concentration in Arts And Sciences and a specialization in Medieval Religious Studies July 9, 2007 Core Faculty Advisor: Robert McAndrews, Ph.D. Union Institute & University Cincinnati, Ohio UMI Number: 3311971 Copyright 2008 by Townsend, Anne Bradford All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3311971 Copyright 2008 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 E. Eisenhower Parkway PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT The purpose of this dissertation is to demonstrate that the Cathar community of Languedoc, far from being heretics as is generally thought, practiced an early form of Christianity. A few scholars have suggested this interpretation of the Cathar beliefs, but none have pursued it critically. In this paper I use two approaches. First, this study will examine the arguments of five contemporary English language scholars who have dominated the field of Cathar research in both Britain and the United States over the last thirty years, and their views have greatly influenced the study of the Cathars. -

ABSTRACT Evelyn Waugh and La Nouvelle Théologie Dan Reid

ABSTRACT Evelyn Waugh and La Nouvelle Théologie Dan Reid Makowsky, Ph.D. Mentor: Ralph C. Wood, Ph.D. This dissertation seeks to provide a more profound study of Evelyn Waugh’s relation to twentieth-century Catholic theology than has yet been attempted. In doing so, it offers a radical revision of our understanding of Waugh’s relation to the Second Vatican Coucil. Waugh’s famous contempt for the liturgical reforms of the early 1960s, his self-described “intellectual” conversion, and his identification with the Council of Trent, have all contributed to a commonplace perception of Waugh as a reactionary Catholic stridently opposed to reform. However, careful attention to Waugh’s dynamic artistic concerns and the deeply sacramental theology implicit in his later fiction reveals a striking resemblance to the most important Catholic theological reform movement of the mid-twentieth century: la nouvelle théologie. By comparing Waugh’s artistic project to the theology of the Nouvelle theologians, who advocated the recovery of a fundamentally sacramental theology, this dissertation demonstrates that the two mirror one another in many of their basic concerns. This mirroring was no mere coincidence. Waugh’s long-time mentor Father Martin D’Arcy was steeped in many of the same sacramentally-minded thinkers as the Nouvelle theologians. Through D’Arcy’s theological influence as well as the deepening of Waugh’s own faith, he, too, developed a sacramental cast of mind. In reading some of the key works of Waugh’s later years, I will show how Waugh realized this sacramental outlook in his art. Ultimately, this dissertation argues that Waugh’s main contribution to the renewal of sacramental thought within Catholicism lies in his portrayal of personal vocation as the remedy for acedia, or sloth, which he considered the “besetting sin” of the age. -

Twentieth-Century French Philosophy Twentieth-Century French Philosophy

Twentieth-Century French Philosophy Twentieth-Century French Philosophy Key Themes and Thinkers Alan D. Schrift ß 2006 by Alan D. Schrift blackwell publishing 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Alan D. Schrift to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2006 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1 2006 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schrift, Alan D., 1955– Twentieth-Century French philosophy: key themes and thinkers / Alan D. Schrift. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-4051-3217-6 (hardcover: alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-4051-3217-5 (hardcover: alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-1-4051-3218-3 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-4051-3218-3 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Philosophy, French–20th century. I. Title. B2421.S365 2005 194–dc22 2005004141 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Set in 11/13pt Ehrhardt by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed and bound in India by Gopsons Papers Ltd The publisher’s policy is to use permanent paper from mills that operate a sustainable forestry policy, and which has been manufactured from pulp processed using acid-free and elementary chlorine-free practices. -

An Analysis of Alfred Loisy's Un Mythe Apologetique

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1980 Misunderstood Mystic: An Analysis of Alfred Loisy's Un Mythe Apologetique Patricia Prendergast Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Prendergast, Patricia, "Misunderstood Mystic: An Analysis of Alfred Loisy's Un Mythe Apologetique" (1980). Master's Theses. 3116. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/3116 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1980 Patricia Prendergast MISUNDERSTOOD MYSTIC: AN ANALYSIS OF ALFRED LOISY'S UN MYTHE APOLOGETIQUE by Patricia Prendergast A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts May 1980 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I should like to take this opportunity to thank Dr. Jon Nilson for his support and encouragement during the writing of this thesis. It was in one of his classes that I first encountered Loisy and through our conversations that the possibility of doing this thesis was manifested. In addition to his helpful suggestions I am exceedingly grateful for his academic integrity which, while concerned to resolve our differences through discussion, never al lowed him to displace my approach with his. -

The Bergsonian Moment: Science and Spirit in France, 1874-1907

THE BERGSONIAN MOMENT: SCIENCE AND SPIRIT IN FRANCE, 1874-1907 by Larry Sommer McGrath A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland June, 2014 © 2014 Larry Sommer McGrath All Rights Reserved Intended to be blank ii Abstract My dissertation is an intellectual and cultural history of a distinct movement in modern Europe that I call “scientific spiritualism.” I argue that the philosopher Henri Bergson emerged from this movement as its most celebrated spokesman. From the 1874 publication of Émile Boutroux’s The Contingency of the Laws of Nature to Bergson’s 1907 Creative Evolution, a wave of heterodox thinkers, including Maurice Blondel, Alfred Fouillée, Jean-Marie Guyau, Pierre Janet, and Édouard Le Roy, gave shape to scientific spiritualism. These thinkers staged a rapprochement between two disparate formations: on the one hand, the rich heritage of French spiritualism, extending from the sixteenth- and seventeeth-century polymaths Michel de Montaigne and René Descartes to the nineteenth-century philosophes Maine de Biran and Victor Cousin; and on the other hand, transnational developments in the emergent natural and human sciences, especially in the nascent experimental psychology and evolutionary biology. I trace the influx of these developments into Paris, where scientific spiritualists collaboratively rejuvenated the philosophical and religious study of consciousness on the basis of the very sciences that threatened the authority of philosophy and religion. Using original materials gathered in French and Belgian archives, I argue that new reading communities formed around scientific journals, the explosion of research institutes, and the secularization of the French education system, brought about this significant, though heretofore neglected wave of thought. -

Doctrine and Discernment: an Approach on the Changeable and Unchangeble Aspsects of Christian Doctrine

Doctrine and discernment: an approach on the changeable and unchangeble aspsects of Christian doctrine Author: Miguel Pedro Lopes de Almeida Teixeira e Melo Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:108456 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2019 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Doctrine and Discernment An approach on the changeable and unchangeable aspects of Christian Doctrine A Study for ‘Paul Preaching in Athens’, by: Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino in Study for ‘Paul Preaching A octrine and iscernment D D An approach on the changeable and unchangeable aspects of Christian Doctrine A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Of Licentiate in Sacred Theology At Boston College — School of Theology and Ministry By Miguel Pedro Lopes de Almeida Teixeira e Melo, S.J. Mentored by Professors Richard Lennan & André Brouillette, S.J. 2019 To my grandmother Bia and Fr. Adolfo Nicolás, SJ 1 Contents Contents 2 Acknowledgements 4 Introduction 5 ON THE CHANGEABLE AND UNCHANGEABLE ASPECTS OF DOCTRINE 10 I — The history of the distinction between changeable and unchangeable 10 1.1. On the changeable and unchangeable and the reception process of Vatican II 11 1.2. Historicity as background for the debate of the Changeable and Unchangeable 12 1.1.1. The Tubingen School 14 1.1.2. The Oxford Movement 15 1.1.3. The Roman School, Modernism and the hypothesis of Maurice Blondel 18 1.1.4. From Vatican I to Vatican II 20 1.1.5. -

Mary, Dogma, and Psychoanalysis

Journal of Religion and Health, Vol. 24, No. 2, Summer 1985 Elizabeth II Todd psychoanalysis be viewed as contributions that enrich and enhance the special Mary, Dogma, and understanding of the human condition and should be respected assuch. Fur ther, the insights of psychology should not be feared asdefamers of theology. Rather, they should support, reinforce, and complement, even clarify, the Psychoanalysis theological constructs that result in dogma. For example, ifpsychology can demonstrate effectively that dogma arises outofthepsychic needs ofpeople, it should notbeseen asthecompetitor orsubstitute oftheology todevelop, in ELIZABETH H. TODD terpret, and re-interpret dogma. Psychology may be thought to have ABSTRACT: Why does Mary hold her prominent place in Catholic theology to the extent that something very relevant to say about human need and dogma. However, it five specific dogmas have developed around her? Psychoanalytic theory suggests dogma arises should not be feared as precluding theological significance and accuracy and out of the psychic needs of people and psychic needs of people are expressed in dogma. The early the proper place of theology in relation to dogma. Psychological insights views of Erich Fromm, a disciple of Freud, are presented to demonstrate that Marian dogma should not be viewed as a threat to theology. At the same time, and in our arose from the psychic needs of the people. The views of both Catholic and Protestant thinkers are presented, as well as theological and psychiatric views. psychology-oriented culture, psychology should not receive a"carte blanche acceptance into the realm of theology. Both these extremes have their dangers on or publication of and pitfalls. -

Montado 1-Vol

NECROLÓGICAS Julien Green (1900-1998) in memoriam El 13 de agosto de 1998, en la antevíspera de la fiesta de la Asunción de María, mu- rió en París el novelista franco-americano Julien Green, a la edad de noventa y ocho años. De padres norteamericanos, Green había nacido en la capital de Francia el 6 de septiembre de 1900. Último hijo de una familia numerosa, creció como un francés rodeado de cinco hermanas y de una madre que le enseñó la lengua inglesa y le transmitió la fe protestante. En la Navidad de 1914 murió la madre de los Green y nueve meses después, con quince años recién cumplidos, Julien Green se convierte al catolicismo, religión que no abandonó jamás. Instruido convenientemente, recibe el bautismo en la primavera de 1916. El sacerdote que le atiende suscita en él la posibilidad de ingresar en la Orden Benedictina. Apenas terminado el bachillerato, se alistó como voluntario en los servicios auxiliares del ejército americano y pasó un invierno sirviendo como conductor de ambulancia en el frente de Italia. Después de la guerra estudió tres años en la Universidad de Virginia. A su vuelta a París, en 1922, cons- ciente de su homosexualidad, decide no entrar en religión y dedicarse al arte, primero a la pintura, que pronto abandona, y más tarde a la novela. Sus cuatro primeras obras, Mont-Cinère (1926), Adrienne Mesurat (1927), Le Voya- geur sur la terre (1927) y Léviathan (1929) obtuvieron un éxito rotundo: se difundieron con amplitud entre un público francés que se quedó perplejo y unos lectores anglosajones que recuperaron de golpe su mejor tradición narrativa, recibieron premios y fueron saludadas con entusiasmo por una intelectualidad que, con André Gide a la cabeza, subrayaron preci- samente la extraterritorialidad del joven novelista. -

Catholic Working Group After Its Meeting in Kyiv (Ukraine) in November 2009—On Interpreting Vatican I1

Appendix Communique of Saint Irenaeus Joint Orthodox- Catholic Working Group after Its Meeting in Kyiv (Ukraine) in November 2009—on Interpreting Vatican I1 The Saint Irenaeus Joint Orthodox-Catholic Working Group met from 4th to 8th November 2009 for its sixth session in Kiev at the invitation of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate). During a meeting with His Beatitude Metropolitan Volodymyr of Kiev and all Ukraine the members of the group expressed their deep gratitude for the hospitality and the possibility to meet in the Monastery of the Caves. The Saint Irenaeus Joint Orthodox-Catholic Working Group consists of 26 theologians, 13 Orthodox and 13 Catholic from different European countries and the USA. It was founded in Paderborn (Germany) in 2004 and has held meetings in Athens (Greece), Chevetogne (Belgium), Belgrade (Serbia) and Vienna (Austria). The theme of the Working Group’s sixth session was “The First Vatican Council—its historical context and the meaning of its definitions”. It continued the series of discussions examining the doctrine of primacy in the context of the concrete exercise of primacy. The results of the common studies were formulated in the following theses: 1. The definitions of the first Vatican Council can only be understood rightly if one takes into account their historical context, which had a strong influence on the formulation of the dogmas of the universal jurisdiction and the infallibility of the pope. The Catholic Church in Western Europe in the second half of the 19th century found itself confronted by three challenges: an ecclesiological challenge expressed primarily in Gallicanism, a political challenge from the 166 APPENDIX increasing state control of the Church, and an intellectual challenge from developments in modern science.