Mary in the Doctrine of Berulle on the Mysteries of Christ Vincent R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. Augustine and the Doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ Stanislaus J

ST. AUGUSTINE AND THE DOCTRINE OF THE MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST STANISLAUS J. GRABOWSKI, S.T.D., S.T.M. Catholic University of America N THE present article a study will be made of Saint Augustine's doc I trine of the Mystical Body of Christ. This subject is, as it will be later pointed out, timely and fruitful. It is of unutterable importance for the proper and full conception of the Church. This study may be conveniently divided into four parts: (I) A fuller consideration of the doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ, as it is found in the works of the great Bishop of Hippo; (II) a brief study of that same doctrine, as it is found in the sources which the Saint utilized; (III) a scrutiny of the place that this doctrine holds in the whole system of his religious thought and of some of its peculiarities; (IV) some consideration of the influence that Saint Augustine exercised on the development of this particular doctrine in theologians and doctrinal systems. THE DOCTRINE St. Augustine gives utterance in many passages, as the occasion de mands, to words, expressions, and sentences from which we are able to infer that the Church of his time was a Church of sacramental rites and a hierarchical order. Further, writing especially against Donatism, he is led Xo portray the Church concretely in its historical, geographical, visible form, characterized by manifest traits through which she may be recognized and discerned from false chuiches. The aspect, however, of the concept of the Church which he cherished most fondly and which he never seems tired of teaching, repeating, emphasizing, and expound ing to his listeners is the Church considered as the Body of Christ.1 1 On St. -

The Dialogue Between Religion and Science in Today's World from The

International Journal of Orthodox Theology 8:3 (2017) 203 urn:nbn:de:0276-2017-3075 Gavril Trifa The Dialogue between Religion and Science in Today’s World from the View of Orthodox Spirituality Abstract One of the core issues of today’s world, the dialogue between science and religion has recently come to the attention of new fields of knowledge, which points to a change in some of the “classical” elements. Having a different history in the East and the West, in Catholic and Orthodox Christianity, the relation between faith and science has lived through some problematic centuries, marked by the attempt of some scientific domains to prove the universe’s materialist ontology and thus the uselessness of religion. This paper aims to present an overview of the Rev. Assist. Prof. Ph.D. stages that marked the often radical Gavril Trifa, Faculty of separation of science from religion, by Orthodox Theology of the highlighting the mutations recorded West University of Timi- during the past few decades not only şoara, Romania 204 Gavril Trifa in society but also in the lives of the young, as a result of the unprecedented development of technology. With technology failing to raise both communication and interpersonal communication to the anticipated level, recent research does not hesitate in emphasizing the unfavourable consequences bring about by the development of the means of communication, regarding the human being’s relation to oneself and one’s neighbours. The solutions we have identified enable an update of the patristic model concerning the relation between religion and science, in the spirit of humility, the one that can bring the Light of life. -

![Amb-CF] Ambrose of Milan, on the Christian Faith](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8058/amb-cf-ambrose-of-milan-on-the-christian-faith-888058.webp)

Amb-CF] Ambrose of Milan, on the Christian Faith

Bibliography Ancient Sources/Dogmatic Works [Ale-LAT] Alexander of Alexandria, Letter to Alexander of Thessalonica [Amb-CF] Ambrose of Milan, On the Christian Faith [ANPF] Ante-Nicene Fathers, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers (38 vols.), Roberts, Alexander, Donaldson, James (eds.), 1885, Hendrickson Publishers [Aqu-SCG] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Contra Gentes [Ar-LAA] Arius, Letter to Alexander of Alexandria [Ar-LC] Arius, Letter to the Emperor Constantine [Ar-LEN] Arius, Letter to Eusebius of Nicomedia [Ar-TH] Arius, Thalia [Ari-BW] Aristotle, The Basic Works of Aristotle (Ed. Richard McKeon), The Modern Library, 2001 (1941) [Aris-APOL] Aristides, The Apology of Aristides [Ath-AS] Athanasius, Letters to Serapion Concerning the Holy Spirit [Ath-CG] Athanasius of Alexandria, Contra Gentes [Ath-DI] Athanasius of Alexandria, De Incarnatione Verbi Dei [Ath-DS] Athanasius of Alexandria, De Synodis [Ath-OCA] Athanasius of Alexandria, Orationes contra Arianos [Athen-PC] Athenagoras of Athens, A Plea for the Christians [Athen-RD] Athenagoras of Athens, The Resurrection of the Dead [Aug-DFC] Augustine of Hippo, On the Faith and the Creed [Aug-DT] Augustine of Hippo, De Trinitate 1 [BAR] The Epistle of Barnabas [Bas-DSS] Basil of Caesarea, De Spiritu Sancto [Bas-EP] Basil of Caesarea, Select Epistles [Bon-DQT] Bonaventure, Disputed Questions on the Mystery of the Trinity [Bon-SJG] Bonaventure, The Soul’s Journey into God [CCC] Catechism of the Catholic Church, Image, 1997 [CleRom-COR] Clement of Rome, First Epistle to the Corinthians [CF] The Christian Faith in the Doctrinal Documents of the Catholic Church, J. Neuner, S.J., J. Dupuis, S.J., Jacques Dupuis (ed.), Alba House, 2001 (seventh revised and enlarged edition) [Cyr-CL] Cyril of Jerusalem, Catechetical Lectures [DID] The Didache [DIOG] The Epistle to Diognetus [ECW] Early Christian Writings, Staniforth, Maxwell (tr.), Louth, Andrew (ed.), Penguin, 1987 [GPTA] Greek Philosophy: Thales to Aristotle, Allen, R. -

Reading Records of Literary Authors: a Comoatisom.Of Some Publishedfaotebocks

DOCUMENT INSURE j ED41.820. CS 204 003 0 AUTHOR Murray, Robin Mark '. TITLE. Reading Records of Literary Authors: A ComOatisom.of Some Publishedfaotebocks. PUB DATE Dec 77 NOTE 118p.; N.A. thesis, The Ilniversity.of Chicago . I EDRS PRICE f'"' NF-S0.83 HC-$6.01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Authors; Bibliographies;_ Rooks; ,ocompcsiticia (Literary); *Creative Writing; *Diariei; Literature* Masters Theses; *Poets; Reading Habits; Reading Materials; *Recrtational Reading; Study Habits IDENTIFIERS Notebooks;.*Note Taking - ABSTRACT The significance ofauthore reading notes may lie not only in their mechanical function as inforna'tion storage devices providing raw materials for writing, but also in their ability to 'concentrate and to mobilize the latent ,emotional and. creative 1 resources of their keepers. This docmlent examines records of 'reading found in the published notebcols'of eight najcr_British.and United States writers of the sixteenth through twentieth. centuries. Through eonparison of their note-taking practices, the following topics are explored: how each author came to make reading notes, the,form.in which notes were' made, and the vriteiso habits of consulting; and using their notes (with special reference to distinctly literary uses). The eight writers whose notebooks ares-exaninea in dtpth are Francis Badonc John Milton, Samuel Coleridge,.Ralph V. Emerson, Henry D. Thoreau, Mark Twain, Thomas 8ardy, and Thomas Violfe.:The trends that emerge from these eight case studiesare discussed, and an extensive bibliograity of published -

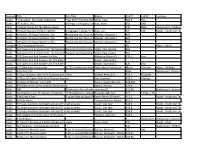

Resource Typeitle Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Location Books

Resource TitleType Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Location Books "Impossible" Marriages Redeemed They Didn't End the StoryMiller, in the MiddleLeila 265.5 MIL Books "R" Father, The 14 Ways To Respond To TheHart, Lord's Mark Prayer 242 HAR DVDs 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family JUV Bible Audiovisual - Children's Books 10 Good Reasons To Be A Catholic A Teenager's Guide To TheAuer, Church Jim. Y/T 239 Books - Youth and Teen Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Compact Discs100 Inspirational Hymns CD Music - Adult Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome 265 Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome 265 Books 101 Questions And Answers On Paul Witherup, Ronald D. 235.2 Paul Compact Discs101 Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. Books 101 Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. 220 BRO Compact Discs120 Bible Sing-Along songs & 120 Activities for Kids! Twin Sisters Productions Music Children Music - Children DVDs 13th Day, The DVD Audiovisual - Movies Books 15 days of prayer with Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton McNeil, Betty Ann 235.2 Elizabeth Books 15 Days Of Prayer With Saint Thomas Aquinas Vrai, Suzanne. -

And Post-Vatican Ii (1943-1986 American Mariology)

FACULTAS THEOLOGICA "MARIANUM" MARIAN LffiRARY INSTITUTE (UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON) TITLE: THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF BIBLICAL MARIOLOGY PRE- AND POST-VATICAN II (1943-1986 AMERICAN MARIOLOGY) A thesis submitted to The Theological Faculty "Marianwn" In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Licentiate of Sacred Theology By: James J. Tibbetts, SFO Director: Reverend Bertrand A. Buby, SM Thesis at: Marian Library Institute Dayton, Ohio, USA 1995 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 The Question of Development I. Introduction - Status Questionis 1 II. The Question of Historical Development 2 III. The Question of Biblical Theological Development 7 Footnotes 12 Chapter 2 Historical Development of Mariology I. Historical Perspective Pre- to Post Vatican Emphasis A. Mariological Movement - Vatican I to Vatican II 14 B. Pre-Vatican Emphasis on Scripture Scholarship 16 II. Development and Decline in Mariology 19 III. Development and Controversy: Mary as Church vs. Mediatrix A. The Mary-Church Relationship at Vatican II 31 B. Mary as Mediatrix at Vatican II 37 c. Interpretations of an Undeveloped Christology 41 Footnotes 44 Chapter 3 Development of a Biblical Mariology I. Biblical Mariology A. Development towards a Biblical Theology of Mary 57 B. Developmental Shift in Mariology 63 c. Problems of a Biblical Mariology 67 D. The Place of Mariology in the Bible 75 II. Symbolism, Scripture and Marian Theology A. The Meaning of Symbol 82 B. Marian Symbolism 86 c. Structuralism and Semeiotics 94 D. The Development of Two Schools of Thought 109 Footnotes 113 Chapter 4 Comparative Development in Mariology I. Comparative Studies - Scriptural Theology 127 A. Richard Kugelman's Commentary on the Annunciation 133 B. -

The Cathars of Languedoc As Heretics

PROJECT DEMONSTRATING EXCELLENCE The Cathars of Languedoc as Heretics: From the Perspectives of Five Contemporary Scholars by Anne Bradford Townsend Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a concentration in Arts And Sciences and a specialization in Medieval Religious Studies July 9, 2007 Core Faculty Advisor: Robert McAndrews, Ph.D. Union Institute & University Cincinnati, Ohio UMI Number: 3311971 Copyright 2008 by Townsend, Anne Bradford All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3311971 Copyright 2008 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 E. Eisenhower Parkway PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT The purpose of this dissertation is to demonstrate that the Cathar community of Languedoc, far from being heretics as is generally thought, practiced an early form of Christianity. A few scholars have suggested this interpretation of the Cathar beliefs, but none have pursued it critically. In this paper I use two approaches. First, this study will examine the arguments of five contemporary English language scholars who have dominated the field of Cathar research in both Britain and the United States over the last thirty years, and their views have greatly influenced the study of the Cathars. -

Why Resurrection?

Why Resurrection? Why Resurrection? An Introduction to the Belief in the Afterlife in Judaism and Christianity Carlos Blanco WHY RESURRECTION? An Introduction to the Belief in the Afterlife in Judaism and Christianity Copyright © 2011 Carlos Blanco. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical publications or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any man- ner without prior written permission from the publisher. Write: Permissions, Wipf and Stock Publishers, 199 W. 8th Ave., Suite 3, Eugene, OR 97401. Scripture taken from the New King James Version®. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Pickwick Publications An Imprint of Wipf and Stock Publishers 199 W. 8th Ave., Suite 3 Eugene, OR 97401 www.wipfandstock.com isbn 13: 978-1-60899-772-5 Cataloging-in-Publication data: Blanco, Carlos. Why resurrection? : an introduction to the belief in the afterlife in Judaism and Christianity / Carlos Blanco. xvi + 226 p. ; 23 cm. Including bibliographical references and index. isbn 13: 978-1-60899-772-5 1. Resurrection (Jewish Theology). 2. Resurrection—History of Doctrines—Early Church, ca. 30–600. I. Title. bt872 .b66 2011 Manufactured in the U.S.A. Contents Acknowledgments • vii List of Abbreviations • viii Introduction • ix 1 Theodicy: Philosophy of Religion and the Problem of Evil • 1 2 History and Meaning • 45 3 The Apocalyptic Conception of History, Evil, and Eschatology • 76 4 Death • 137 5 The Kingdom of God • 182 Bibliography • 217 Acknowledgments his book would not have been possible without the help of Tmany people from whose teaching and direct advice I have greatly profited. -

ABSTRACT Evelyn Waugh and La Nouvelle Théologie Dan Reid

ABSTRACT Evelyn Waugh and La Nouvelle Théologie Dan Reid Makowsky, Ph.D. Mentor: Ralph C. Wood, Ph.D. This dissertation seeks to provide a more profound study of Evelyn Waugh’s relation to twentieth-century Catholic theology than has yet been attempted. In doing so, it offers a radical revision of our understanding of Waugh’s relation to the Second Vatican Coucil. Waugh’s famous contempt for the liturgical reforms of the early 1960s, his self-described “intellectual” conversion, and his identification with the Council of Trent, have all contributed to a commonplace perception of Waugh as a reactionary Catholic stridently opposed to reform. However, careful attention to Waugh’s dynamic artistic concerns and the deeply sacramental theology implicit in his later fiction reveals a striking resemblance to the most important Catholic theological reform movement of the mid-twentieth century: la nouvelle théologie. By comparing Waugh’s artistic project to the theology of the Nouvelle theologians, who advocated the recovery of a fundamentally sacramental theology, this dissertation demonstrates that the two mirror one another in many of their basic concerns. This mirroring was no mere coincidence. Waugh’s long-time mentor Father Martin D’Arcy was steeped in many of the same sacramentally-minded thinkers as the Nouvelle theologians. Through D’Arcy’s theological influence as well as the deepening of Waugh’s own faith, he, too, developed a sacramental cast of mind. In reading some of the key works of Waugh’s later years, I will show how Waugh realized this sacramental outlook in his art. Ultimately, this dissertation argues that Waugh’s main contribution to the renewal of sacramental thought within Catholicism lies in his portrayal of personal vocation as the remedy for acedia, or sloth, which he considered the “besetting sin” of the age. -

August 31, 1965 Iii

D.S. I THE INFLUENCE OF THE FRENCH SCWOL OF SPIRITUALITY ON THE WRITINGS OF SUNT LOUIS MARIE DE }KJNTFURT by Sister ?1all'Y IAwrence Corv'1, D.W., M.A. A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University in Partial FultUlment of the Re quirements tor the Degree of Master of Arts Milwaukee. Wisconsin August 31, 1965 iii / PRI1:FACE The problem on hand. is to ascertain the 1nfiuence of the French School ot Spil"1tuality on the mtingS ot Saint !cuts Marie de M:>nt tort. Granted that traces of the teaching ot this school, as weU as ot the French Ignatian School and various Illinor figures are present in the wrks ot Montfort, can he notwithstanding be considered an onginal writer and tounder ot a new sc1'!ool ot spiritual thinking? In this the sis, having first treated o~ , MOpttort"s major themes and then examined the extent' to which his writings were influenced b.Y his predecessors in France, especiall.y B4nille, I propose to reply to the foregoing question in the atfirmative. At this time, I Wish to acknowledge the kind and constructive criticism of Father WUliam J . Kelly, S.J., ot the Theology Department of };arquette Univel"Sit;r who guid$d the writing ot this thesis; and the coopel"ati.on ot :Father BernaJXl Cooke, S.J., Head ot the Theology Depart ment , and ot !bctor Riohard Schneido1", member ot the 'i'heology Depart ment, who With Father Kelly have constituted a committee ot three tor the reading of this thesis. -

Apocalypticism, the Year 1000, and the Medieval Roots of the Ecological Crisis

Apocalypticism, the Year 1000, and the Medieval Roots of the Ecological Crisis Mario Baghos Introduction1 … the very act, the hubristic intent, of placing man in charge of nature caused reverberations that have not yet ceased.2 When Mircea Eliade undertook his groundbreaking work in the history of religions, he was partly concerned to address the rise of the historicist mindset of modern people, who, for centuries, have anthropocentrically construed themselves apart from the natural or cosmic environment. There is much merit to Eliade’s position, which I employ and, together with insights from Alexandru Mironescu, Richard Landes, and Georges Duby, elaborate upon, in order to locate the anthropocentrically motivated disjuncture between nature and history in the early medieval period in an attempt to demonstrate that the current ecological crisis has its antecedents there. Of course, the causal link between the scientific and technological advancements in the Middle Ages and the ecological crisis of our times has already been explored by Lynn White in ‘The Historical Roots of the Ecological Crisis’. White, however, identified the problem as an anthropocentrism inherent to Christianity; an anthropocentrism only contradicted in the ministry of St Francis of Assisi in the thirteenth Mario Baghos is Lecturer in Church History at St Andrew’s Greek Orthodox Theological College in Sydney, and is an Executive Member for the Sydney branch of the Centre for Millennial Studies. 1 This article is the outcome of two conference papers. The first was delivered at the Studies in Religion Research Seminars at the University of Sydney under the title ‘Anthropocentrism and the Dissociation Between Cosmos and History: its Impact on our Study of the Past’ on 4 April 2012. -

Twentieth-Century French Philosophy Twentieth-Century French Philosophy

Twentieth-Century French Philosophy Twentieth-Century French Philosophy Key Themes and Thinkers Alan D. Schrift ß 2006 by Alan D. Schrift blackwell publishing 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Alan D. Schrift to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2006 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1 2006 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schrift, Alan D., 1955– Twentieth-Century French philosophy: key themes and thinkers / Alan D. Schrift. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-4051-3217-6 (hardcover: alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-4051-3217-5 (hardcover: alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-1-4051-3218-3 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-4051-3218-3 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Philosophy, French–20th century. I. Title. B2421.S365 2005 194–dc22 2005004141 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Set in 11/13pt Ehrhardt by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed and bound in India by Gopsons Papers Ltd The publisher’s policy is to use permanent paper from mills that operate a sustainable forestry policy, and which has been manufactured from pulp processed using acid-free and elementary chlorine-free practices.