Luigi Montuori

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kirche Und Schule in Äthiopien

Kirche und Schule in Äthiopien Mitteilungen der Tabor Society e.V. Heidelberg ISSN 1615-3197 Heft 64 / November 2011 Kirche und Schule in Äthiopien, Heft 64 / November 2011 IMPRESSUM KIRCHE UND SCHULE IN ÄTHIOPIEN (KuS) - Mitteilungen der TABOR SOCIETY - Deutsche Gesellschaft zur Förderung orthodoxer Kirchenschulen in Äthiopien e.V. Heidelberg Dieses Mitteilungsblatt ist als Manuskript gedruckt Vorstandsmitglieder der Tabor Society: und für die Freunde und Förderer der Tabor Society bestimmt. 1. Vorsitzender: Pfr. em. Jan-Gerd Beinke Die Tabor Society wurde am 22. März 1976 beim Furtwängler-Str. 15 Amtsgericht Heidelberg unter der Nr. 929 ins 79104 Heidelberg Vereinsregister eingetragen. Das Finanzamt Heidel- Tel.: 0761 - 29281440 berg hat am 21. 07. 2011 unter dem Aktenzeichen 32489/38078 der Tabor Society e.V. Heidelberg den Stellvertr. Vorsitzende und Schriftführerin: Freistellungsbescheid zur Körperschaftssteuer und Dr. Verena Böll Gewerbesteuer für die Kalenderjahre 2005, 2006, Alaunstr. Str. 53 2007 zugestellt. 01099 Dresden Tel.: 0351- 8014606 Darin wird festgestellt, dass die Körperschaft Tabor Society e.V. nach § 5 Abs.1 Nr.9 KStG von der Kör- Schatzmeisterin: perschaftssteuer und nach § 3 Nr. 6 GewStG von der Dorothea Georgieff Gewerbesteuer befreit ist, weil sie ausschließlich und Im Steuergewann 2 unmittelbar steuerbegünstigten gemeinnützigen Zwek- 68723 Oftersheim ken im Sinne der §§ 51 ff. AO dient. Die Körperschaft Tel.: + Fax: 06202 - 55052 fördert, als allgemein besonders förderungswürdig an- weitere Vorstandsmitglieder erkannten gemeinnützigen Zweck, die Jugendhilfe. Dr. Kai Beermann Die Körperschaft ist berechtigt, für Spenden und Mit- Steeler Str. 402 gliedsbeiträge, die ihr zur Verwendung für diese 45138 Essen Zwecke zugewendet werden, Zuwendungs- bestäti- Tel.: 0201 - 265746 gungen nach amtlich vorgeschriebenem Vordruck (§ 50 Abs. -

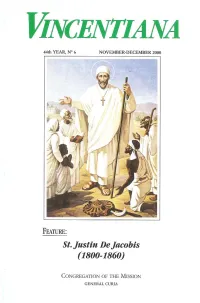

St Justin De Jacobis: Founder of the New Catholic Generation and Formator of Its Native Clergy in the Catholic Church of Eritrea and Ethiopia

Vincentiana Volume 44 Number 6 Vol. 44, No. 6 Article 6 11-2000 St Justin de Jacobis: Founder of the New Catholic Generation and Formator of its Native Clergy in the Catholic Church of Eritrea and Ethiopia Abba lyob Ghebresellasie C.M. Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Ghebresellasie, Abba lyob C.M. (2000) "St Justin de Jacobis: Founder of the New Catholic Generation and Formator of its Native Clergy in the Catholic Church of Eritrea and Ethiopia," Vincentiana: Vol. 44 : No. 6 , Article 6. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana/vol44/iss6/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. St Justin de Jacobis: Founder of the New Catholic Generation and Formator of its Native Clergy in the Catholic Church of Eritrea and Ethiopia by Abba lyob Ghebresellasie, C.M. Province of Eritrea Introduction Biblical References to the Introduction of Christianity in the Two Countries While historians and archeologists still search for hard evidence of early Christian settlements near the western shore of the Red Sea, it is not difficult to find biblical references to the arrival of Christianity in our area. And behold an Ethiopian, eunuch, a minister of Candace, queen of Ethiopia, who was in charge of all her treasurers, had come to Jerusalem to worship... -

Mémoire HDR H. Pennec2019

Historiographie, productions de savoirs missionnaires, terrains, archéologie. Éthiopie XVIe-XXIe siècle Mémoire de recherche inédit présenté en vue de l’habilitation à diriger des recherches par Hervé PENNEC Chargé de recherches au CNRS – section 33 (Institut des mondes aFricains – IMAF/UMR 8171 – CNRS & 243 IRD) Composition du jury : Pierre-Antoine Fabre, Directeur d’Etudes – EHESS (garant) Marie-Laure Derat, Directrice de recherches – CNRS (rapporteure) Henri Médard, Professeur d’histoire à l’Aix-Marseille Université (rapporteur) Antonella Romano, Directrice d’Etudes – EHESS Angelo Torre, Professeur d’histoire à l’Università degli Studi del Piemonte Orientale Date de soutenance : le 8 juin 2019 à l’Ecole des Hautes Etudes en sciences sociales Hervé Pennec Historiographie, productions de savoirs missionnaires, terrains, archéologie. Éthiopie XVIe-XXIe siècle Vol. 2 : Mémoire de recherche inédit présenté en vue de l’habilitation à diriger des recherches EHESS, 2018 2 3 Introduction En février 1541, le roi éthiopien Gälawdéwos (1540-1559), identifié au « prêtre Jean », reçut des renforts militaires, destinés à son prédécesseur, Lebnä Dengel mort en septembre 1540, du roi João III (1521-1557) de Portugal. À la tête de cette armée (environ 400 soldats), se trouvait Christovão da Gama (un des fils du déjà célèbre navigateur1). Cet événement fut le point d’orgue des relations entre le Portugal et l'Éthiopie, dont les origines politiques remontaient à un demi-siècle. Sur un plan théologique, fantasmatique, elles étaient multiséculaires. La légende du prêtre Jean remonte en effet au milieu du XIIe siècle. Elle prend source dans une lettre apocryphe soi-disant adressée à l'empereur de Byzance Manuel Ier Comnène (1143-1180) et à l'empereur du Saint Empire germanique, Frédéric Ier Barberousse (1152-1190). -

Aethiopica 15 (2012) International Journal of Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies

Aethiopica 15 (2012) International Journal of Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies ________________________________________________________________ TEDROS ABRAHA, Pontifical Oriental Institute, Rome Article The GƼ’Ƽz Version of Philo of Carpasia’s Commentary on Canticle of Can- ticles 1:2–14a: Introductory Notes Aethiopica 15 (2012), 22–52 ISSN: 2194–4024 ________________________________________________________________ Edited in the Asien-Afrika-Institut Hiob Ludolf Zentrum für Äthiopistik der Universität Hamburg Abteilung für Afrikanistik und Äthiopistik by Alessandro Bausi in cooperation with Bairu Tafla, Ulrich Braukämper, Ludwig Gerhardt, Hilke Meyer-Bahlburg and Siegbert Uhlig The GƼʞƼz Version of Philo of Carpasia߈s Commentary on Canticle of Canticles 1:2߃14a: Introductory Notes TEDROS ABRAHA, Pontifical Oriental Institute, Rome Premise The fragment with Philo of Carpasia߈s explanation of Canticle of Canticles 2߃14a bears the title ҧџՅю֓ ѢрѐӇ TƼrgwame SÃlomon ߋInterpretation :1 of Salomonߌ. In his shelf list of the Ethiopian manuscripts kept at the Ethi- opian archbishopric in Jerusalem,1 Ephraim Isaac makes the following re- marks in relation to the manuscript JE300E (MS 119 at the Ethiopian arch- bishopric in Jerusalem): This is the title given to the work which contains, beside other compo- site monastic works, a commentary to Song of Songs 1: 2߃14a (fols. 3a߃ 20a). This commentary is the work of Philo of Carpasia (Philon Philgos) (c. 400). I thank Prof. Sebastian Brock who helped to identify this work with the help of Rev. Roger Cowley.2 The commentary in- corporated into the catena of Procopius is published in PG KL. (In Lat- in, see Epiphanius of Salamis). As far as I know this is the only known Ms of this work in Geʞez. -

Local History of Ethiopia Aka - Alyume © Bernhard Lindahl (2005)

Local History of Ethiopia Aka - Alyume © Bernhard Lindahl (2005) HC... Aka (centre in 1964 of Bitta sub-district) 07/35? [Ad] HFC14 Akab Workei (Aqab Uorchei) 13°42'/36°58' 877 m 13/36 [+ Gz] akabe saat: aqabe sä'at (Geez?) "Guardian of the Hour", at least from the 15th century a churchman attached to the palace and also in the 18th century "the first religious officer at the palace"; akkabi (aqqabi) (A) guardian, custodian; (T) collector, convener HFE50 Akabe Saat (Acab Saat, Aqab Se'at, Akabie Se'at) 14/38 [+ Gu Ad Gz] (mountain & place) 14°06'/38°30' 2385 m (sub-district & its centre in 1964) 1930s Towards midday on 29 February 1936 the 'April 21st' Division, at the head of a long column, reached the heights of Acab Saat without encountering the enemy, and consolidated its position there. [Badoglio (Eng.ed.)1937 p 115] On 29 February as above, Blackshirt and voluntary soldier Francesco Battista fought during four hours at Akabe Saat before he was killed. He was posthumously honoured with a gold medal. [G Puglisi, Chi è? .., Asmara 1952] 1980s According to government reports TPLF forces deployed in the May Brazio-Aqab Se'at front around 8-9 February 1989 were estimated to be three divisions, two heavy weapon companies and one division on reserve. [12th Int. Conf. of Ethiopian Studies 1994] HED98 Akabet (Ak'abet, Aqabet) 11°44'/38°17' 3229 m 11/38 [Gz q] HDM31 Akabido 09°21'/39°30' 2952 m 09/39 [Gz] akabo: Akebo Oromo penetrated into Gojjam and were attacked by Emperor Fasiledes in 1649-50 ?? Akabo (Accabo) (mountain saddle) c1900 m ../. -

Edited and Unedited Writings of St. Justin De Jacobis

Vincentiana Volume 44 Number 6 Vol. 44, No. 6 Article 10 11-2000 Edited And Unedited Writings of St. Justin De Jacobis Giuseppe Guerra C.M. Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Guerra, Giuseppe C.M. (2000) "Edited And Unedited Writings of St. Justin De Jacobis," Vincentiana: Vol. 44 : No. 6 , Article 10. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana/vol44/iss6/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Edited And Unedited Writings of St. Justin De Jacobis by Giuseppe Guerra, CM Province of Naples St Justin wrote very much. On the one hand, during the first period of his life spent in his native country (1800-1839), we have only numerous letters from him. On the other hand, during the most difficult period of his life, the mission in Abyssinia (1839-1860), despite the absolute lack of conveniences and writing materials, he produced page after page, driven by apostolic needs. The biographies of De Jacobis, speaking of his writings, immediately state that they are all unedited,1 except for the Catechismo Amarico [Amharic Catechism], printed in Rome by Propaganda Fide in 1850. This year, on the occasion of the bicentenary of his birth, the Naples Province has undertaken the printing of his Diario, publishing it as Volume I of his Scritti, which it intends to continue publishing in their entirety. -

CRISTIANESIMO E ARTE in ETIOPIA La Cattedrale Cattolica Di Emdibir Musiè Gebreghiorghis, Dal 2003 Eparca Di Emdibir, Zona Guraghe E Wolisso in Etiopia

CRISTIANESIMO E ARTE IN ETIOPIA La cattedrale cattolica di Emdibir Musiè Gebreghiorghis, dal 2003 Eparca di Emdibir, Zona Guraghe e Wolisso in Etiopia. Al suo ingresso in dioce- si ha trovato una chiesa bella e accogliente, dedicata a Sant’Antonio di Padova, ma spoglia e costruita in stile europeo. Trattandosi di una Eparchia e volendo seguire le indicazioni del decreto sulle Chiese Orientali, il Ve- scovo dapprima ha provveduto a una triplice suddivi- sione della chiesa secondo la tradizione etiopica. Poi ha curato la decorazione dell’interno. L’invito delle sue pareti spaziose a fare qualcosa per riempire il vuoto è stato irresistibile. Così ha invitato l’artista Melake Genet con suo figlio Qesi per eseguire gli affreschi, con temi e stile etiopico. Questo lavoro è durato ben sette anni. Ora la cattedrale cattolica di Emdibir risplende in tutta la sua magnificenza. Il Vescovo Musiè Gebreghiorghis ora si augura che essa risvegli un apprezzamento sem- pre maggiore del patrimonio culturale e artistico di una chiesa apostolica di matrice orientale in piena comunio- ne con la sede di San Pietro. Musiè Ghebreghiorghis, Eparch of Emdibir, Guraghe and Wolisso Zone, Ethiopia, ever since 2003. When he took over the pastoral ministry of diocese he found a beautiful and welcoming western style architecture church with spacious walls without paintings, dedicated to St. Anthony of Padua. As the Eparchy was of Eastern tradition and in compliance with the directives of the Decree on Oriental Churches, the bishop first worked on the threefold division of the Church in line with the Ethiopian tradition; then he decorated it with paintings. -

Devotion to St. Justin De Jacobis in Eritrea and Ethiopia

Vincentiana Volume 44 Number 6 Vol. 44, No. 6 Article 9 11-2000 Devotion to St. Justin de Jacobis in Eritrea and Ethiopia Iyob Ghebresellasie C.M. Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Ghebresellasie, Iyob C.M. (2000) "Devotion to St. Justin de Jacobis in Eritrea and Ethiopia," Vincentiana: Vol. 44 : No. 6 , Article 9. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana/vol44/iss6/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Devotion to St. Justin de Jacobis in Eritrea1 and Ethiopia2 By Iyob Ghebresellasie, C.M. Province of Eritrea In speaking about devotion to St. Justin I should say in advance that this refers in a special way to the Catholics in Eritrea and in some areas of Ethiopia. As is well known, St. Justin's apostolate was mainly in the country which at one time was known as Abyssinia, but which today is two countries, Eritrea and Ethiopia. 1. Christianity before St. Justin's evangelization The first Christian seed was planted along the Eritrean coast in the first century,3 and in time, by crossing the Eritrean plateau, it spread into northern Ethiopia. From the beginning of the fourth century until the 18th, before St. -

WHERE IS YOUR BROTHER.Pages

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! “WHERE IS YOUR BROTHER?” (Gn. 4:9) ! ! ! ! ! ! Pastoral Letter of the Catholic Bishops of Eritrea ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! (Translation from the original Tigrinya text) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Asmara – Eastertide 25th. May, 2014 “Where is your brother?” (Gn. 4:9) ! Greeting 1. To our “… true child(ren) in the faith …” and to all men and women of good will, “… Grace, mercy and peace from God the Father and from Christ Jesus our Lord” (1 Tm. 1:2). In this Easter season when we celebrate Christ’s victory over sin and death, it is our sincere wish that you re-clothe yourselves in the wisdom and understanding that He has poured out upon us so abundantly (cf. Ep. 5:8-9). ! Beloved brothers and sisters in Christ, our faith is not merely “… the guarantee of the blessings we hope for, or the proof of the existence of realities that are unseen …” but through it “… we know that the ages were created by a word from God …” (Heb. 11:1-3) and in its light we understand the true meaning of the events unfolding in this world. Encouraged by this faith, we now address this present Pastoral letter to you. ! Preface 2. In these times in which so many men and women, duped by a mistaken understanding of progress, distance themselves even more from the faith, “We always thank God for you all, mentioning you in our prayers continually. We remember before our God and Father how active is the faith, how unsparing is the love, how persevering is the hope which you have from our Lord Jesus Christ” (1 Th. -

![Vincentiana Vol. 52, No. 6 [Full Issue]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0001/vincentiana-vol-52-no-6-full-issue-4030001.webp)

Vincentiana Vol. 52, No. 6 [Full Issue]

Vincentiana Volume 52 Number 6 Vol. 52, No. 6 Article 1 2008 Vincentiana Vol. 52, No. 6 [Full Issue] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation (2008) "Vincentiana Vol. 52, No. 6 [Full Issue]," Vincentiana: Vol. 52 : No. 6 , Article 1. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana/vol52/iss6/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Via Sapientiae: The Institutional Repository at DePaul University Vincentiana (English) Vincentiana 12-31-2008 Volume 52, no. 6: November-December 2008 Congregation of the Mission Recommended Citation Congregation of the Mission. Vincentiana, 52, no. 6 (November-December 2008) This Journal Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentiana at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana (English) by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INCENTIANA 52' Year - N. 6 November-December 2008 Fruits of the Mission CONGREGATION OF THE MISSION GENERAL CURIA General Curia 429 Athent 2008 433 Tempo Fork, Circular Feature: Fruits of the Mission 439 Presentation - Julio Suescun Olcoz, CM. 441 The Most Precious Fruit of the Missionary Apostolate of St Justin de Jacobis. -

VT-2000-06-ENG-ALL.Pdf

HOLY SEE Appointments The Holy Father John Paul II has raised the Apostolic Prefecture of Tierradentro to the rank of Apostolic Vicariate, with the same denomination and territorial configuration. Moreover, His Holiness has named Fr. Jorge García Isaza, C.M. as the first Apostolic Vicar of Tierradentro (Colombia), assigning him the Episcopal See of Budua. Until now, Fr. García was Apostolic Prefect of the same Ecclesiastical Circumscription. (L’Osservatore Romano, February 27, 2000, p. 1) The Holy Father John Paul II has named Fr. Cristoforo Palmieri, C.M. Apostolic Administrator of Rrëshen (Albania). Up to the present, he was Diocesan Administrator of this same diocese. (L’Osservatore Romano, March 6-7, 2000, p. 1) The Holy Father John Paul II has named Fr. Anton Stres, C.M. Auxiliary Bishop of Maribor in Slovenia, assigning to him the titular episcopal see of Ptuj. Up to the present, Fr. Stres has been dean of the Theology Faculty of Ljubljana. (L’Osservatore Romano, May 14, 2000, p. 2) Decree On 1 July 2000, in the presence of the Holy Father, was promulgated the decree regarding the heroic virtues of the Servant of God, Marco Antonio Durando, priest of the Congregation of the Mission of St. Vincent de Paul and Founder of the Institute of the Sisters of Jesus of Nazareth, born on 22 May 1801 at Mondovì (Italy) and died on 10 December 1880 at Turin (Italy). (L’Osservatore Romano, July 2, 2000, p. 1) Letter The Holy Father John Paul II wrote to His Excellency Gaston Poulain, Bishop of Périgueux and Sarlat, a letter dated September 8, on the occasion of the fourth centenary of the priestly ordination of St. -

![Vincentiana Vol. 33, No. 1 [Full Issue]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7077/vincentiana-vol-33-no-1-full-issue-4837077.webp)

Vincentiana Vol. 33, No. 1 [Full Issue]

Vincentiana Volume 33 Number 1 Vol. 33, No. 1 Article 1 1989 Vincentiana Vol. 33, No. 1 [Full Issue] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1989) "Vincentiana Vol. 33, No. 1 [Full Issue]," Vincentiana: Vol. 33 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana/vol33/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Via Sapientiae: The Institutional Repository at DePaul University Vincentiana (English) Vincentiana 2-28-1989 Volume 33, no. 1: January-February 1989 Congregation of the Mission Recommended Citation Congregation of the Mission. Vincentiana, 33, no. 1 (January-February 1989) This Journal Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentiana at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana (English) by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONGREGATIO MISS IONIS VINCENTIANA 0 1989 VSI.PER. 255.77005 V775 CURIA GENERALITIA v. 33 Via di Bravetta, 159 no.1 00164 ROMA 1989 SUMMARIUM ACTA SAN('TAE SEDIS - Letter of the Pt ii. orator General to Cong. for Divine \Nor- ship ...._....... .. .............................................................. - Decretum Congieg pro Cultu Divino (pro lingua polona) CURIA GENERALITIA I - Litterae Superioris Gerteralis - a toute la Congregation (28.1.1989) 3 to the Congregation (Lent 1989) 4 2 - Some Reflections on Evangelical Poverty in the Congre- gation - The Gen.