Green Book Chapter 17 V2 0 143 17.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Typhoid Vaccine W H a T Y O U N E E D T O K N O W

TYPHOID VACCINE W H A T Y O U N E E D T O K N O W Many Vaccine Information Statements are available in Spanish and other languages. See www.immunize.org/vis. What is typhoid? •Travelers to parts of the world where typhoid is 1 common. (NOTE: typhoid vaccine is not 100% Typhoid (typhoid fever) is a serious disease. It is effective and is not a substitute for being caused by bacteria called Salmonella Typhi. careful about what you eat or drink.) Typhoid causes a high fever, weakness, stomach •People in close contact with a typhoid carrier. pains, headache, loss of appetite, and sometimes a •Laboratory workers who work with Salmonella rash. If it is not treated, it can kill up to 30% of Typhi bacteria. people who get it. Some people who get typhoid become “carriers,” Inactivated Typhoid Vaccine (Shot) who can spread the •Should not be given to children younger than 2 disease to years of age. others. •One dose provides protection. It should be given Generally, at least 2 weeks before travel to allow the vaccine people get time to work. typhoid from contaminated •A booster dose is needed every 2 years for people food or water. Typhoid is not common in the U.S., who remain at risk. and most U.S. citizens who get the disease get it Live Typhoid Vaccine (Oral) while traveling. Typhoid strikes about 21 million people a year around the world and kills about •Should not be given to children younger than 6 200,000. years of age. -

Vaccine Adjuvants Derived from Marine Organisms

biomolecules Review Vaccine Adjuvants Derived from Marine Organisms Nina Sanina Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Biotechnology, School of Natural Sciences, Far Eastern, Federal University, Sukhanov Str., 8, Vladivostok 690091, Russia; [email protected]; Tel.: +7-423-265-2429 Received: 10 July 2019; Accepted: 1 August 2019; Published: 3 August 2019 Abstract: Vaccine adjuvants help to enhance the immunogenicity of weak antigens. The adjuvant effect of certain substances was noted long ago (the 40s of the last century), and since then a large number of adjuvants belonging to different groups of chemicals have been studied. This review presents research data on the nonspecific action of substances originated from marine organisms, their derivatives and complexes, united by the name ‘adjuvants’. There are covered the mechanisms of their action, safety, as well as the practical use of adjuvants derived from marine hydrobionts in medical immunology and veterinary medicine to create modern vaccines that should be non-toxic and efficient. The present review is intended to briefly describe some important achievements in the use of marine resources to solve this important problem. Keywords: squalene; cucumariosides; chitosan; fucoidans; carrageenans; laminarin; alginate 1. Introduction The oil-in-water-based complete Freund’s adjuvant developed by Jules Freund and Katherine McDermott in 40s of last century is the first vaccine adjuvant. The basis of immune stimulation and provide immunologists with a way to stimulate the production of antibodies and cellular immune responses to weak antigens. This elaboration allowed to establish the basis of immune stimulation and provide immunologists with an instrument to stimulate the production of antibody and cellular immune responses to weak antigens. -

2021 Medicare Vaccine Coverage Part B Vs Part D

CDPHP® Medicare Advantage Vaccine Coverage Guide Part B (Medical) vs. Part D (Pharmacy) Medicare Part B (Medical): Medicare Part D (Pharmacy): Vaccinations or inoculations Vaccinations or inoculations are included when the administration is (except influenza, pneumococcal, reasonable and necessary for the prevention of illness. and hepatitis B for members at risk) are excluded unless they are directly related to the treatment of an injury or direct exposure to a disease or condition. • Influenza Vaccine (Flu) • BCG Vaccine • Pneumococcal Vaccine • Diphtheria/Tetanus/Acellular Pertussis Vaccine (ADACEL, (Pneumovax, Prevnar 13) BOOSTRIX, DAPTACEL, INFANRIX) • Hepatitis B Vaccine • Diphtheria/Tetanus/Acellular Pertussis/Inactivated Poliovirus (Recombivax, Engerix-B) Vaccine (KINRIX, QUADRACEL) for members at moderate • Diphtheria/Tetanus Vaccine (DT, Td, TDVAX, TENIVAC) to high risk • Diphtheria/Tetanus/Acellular Pertussis/Inactivated Poliovirus Vac • Other vaccines when directly cine/ Haemophilus Influenzae Type B Conjugate Vaccine (PENTACEL) related to the treatment of an • Diphtheria/Tetanus/Acellular Pertussis/Inactivated Poliovirus injury or direct exposure to a Vaccine/Hepatitis B Vaccine (PEDIARIX) disease or condition, such as: • Haemophilus Influenzae Type B Conjugate Vaccine (ActHIB, PedvaxHIB, • Antivenom Sera Hiberix) • Diphtheria/Tetanus Vaccine • Hepatitis A Vaccine, Inactivated (VAQTA) (DT, Td, TDVAX, TENIVAC) • Hepatitis B Vaccine, Recombinant (ENGERIX-B, RECOMBIVAX HB) • Rabies Virus Vaccine for members at low risk (RabAvert, -

Routine Immunizations

Drug and Biologic Coverage Policy Effective Date ............................................... 7/1/2021 Next Review Date ......................................... 4/1/2022 Coverage Policy Number .................................. 9001 Routine Immunizations Table of Contents Related Coverage Resources Coverage Policy ................................................... 1 Preventive Care Services General Background ............................................ 2 Covid-19 Vaccine Coding/Billing Information .................................... 3 References .......................................................... 7 INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE The following Coverage Policy applies to health benefit plans administered by Cigna Companies. Certain Cigna Companies and/or lines of business only provide utilization review services to clients and do not make coverage determinations. References to standard benefit plan language and coverage determinations do not apply to those clients. Coverage Policies are intended to provide guidance in interpreting certain standard benefit plans administered by Cigna Companies. Please note, the terms of a customer’s particular benefit plan document [Group Service Agreement, Evidence of Coverage, Certificate of Coverage, Summary Plan Description (SPD) or similar plan document] may differ significantly from the standard benefit plans upon which these Coverage Policies are based. For example, a customer’s benefit plan document may contain a specific exclusion related to a topic addressed in a Coverage Policy. In the event -

Integration of Typhoid Conjugate Vaccine in National Immunization Schedules: Opportunities and Challenges

Integration of typhoid conjugate vaccine in national immunization schedules: Opportunities and Challenges. Integration of typhoid9th conjugateInternational vaccine Conferencein national immunization on Typhoid schedules: and Opportunities and invasiveChallenges. NTS Disease 30/04 – 3/05, 2015. Nusa Dua, Bali Objective Review the existing clinical data on Vi conjugate vaccines, based on literature and our experience with Typbar-TCV to ascertain data sufficiency to assist global policy formualtion. Presentation Outline • Need for typhoid vaccine – Disease burden • Typhoid conjugate vaccines – Key considerations • Available data from typhoid conjugate vaccines (TCV) • Programmatic considerations • Integration of TCV into childhood immunization programs Typhoid epidemiology Disease Burden This disease is endemic in most developing countries. Cases/100,00 persons Highly Endemic >100 Endemic 10-100 Sporadic <10 21 million cases worldwide, mortality estimates of 216,000 to 600,000. http://www.who.int/immunization/topics/en/ http://www3.chu-rouen.fr/Internet/services/sante_voyages/pathologies/typhoide/ Age stratified disease burden 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 Proportion of Cases of Proportion Age groups Crump JA, et al. Bull World Health Organ 2004;82:346-353 Typhoid fever incidence – Asia and Africa • High incidence of typhoid fever in the region. • High incidence in urban slums; rates similar • Substantial regional variation in incidence. to those from Asia. • “Modified” Passive srvlnce. • Lower burden in rural children from Ghana (and Lwak, Kenya), compared to urban Ochiai RL, et al. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:260-268. Breiman, RF et. al, PLoS One. 2012; 7(1): e29119. areas; regional differences Marks, F et. al, Emerg Infect Dis. 2010; 16(11): 1796–1797. -

Weekly Epidemiological Record Relevé Épidémiologique Hebdomadaire

2017, 92, 13-20 No 2 Weekly epidemiological record Relevé épidémiologique hebdomadaire 13 JANUARY 2017, 92th YEAR / 13 JANVIER 2017, 92e ANNÉE No 2, 2017, 92, 13–20 http://www.who.int/wer Global Advisory Committee Comité consultatif mondial Contents on Vaccine Safety, pour la sécurité des vaccins, er 13 Global Advisory Committee on 30 November – 1 December 30 novembre - 1 décembre Vaccine Safety, 30 November 2016 2016 – 1 December 2016 The Global Advisory Committee on Le Comité consultatif mondial pour la sécurité Vaccine Safety (GACVS), an independent des vaccins (GACVS) est un organe consultatif Sommaire expert clinical and scientific advisory indépendant composé d’experts cliniques et 13 Comité consultatif mondial body, provides WHO with scientifically scientifiques qui fournissent à l’OMS des pour la sécurité des vaccins, rigorous advice on vaccine safety issues of conseils d’une grande rigueur scientifique sur 30 novembre - 1er décembre potential global importance.1 GACVS held des problèmes de sécurité des vaccins suscep- 2016 its 35th meeting in Geneva, Switzerland, tibles d’avoir une portée mondiale.1 Le GACVS on 30 November and 1 December 2016.2 a tenu sa 35e réunion à Genève (Suisse) les The Committee examined 2 generic issues: 30 novembre et 1er décembre 2016.2 Il a abordé updates on its operations following a 2 questions génériques, avec une mise à jour review conducted in 2014, and progress sur ses activités suite à une analyse réalisée with developing the Vaccine Safety Net. It en 2014 et un aperçu des progrès accomplis also reviewed vaccine-specific safety issues dans la mise en place du Réseau pour la sécu- concerning typhoid vaccines, yellow fever rité des vaccins. -

Combined Hepatitis a Virus (Inactivated) and Typhoid Polysaccharide Vaccine Patient Group Direction (PGD)

PHE publications gateway number: GW-1014 Combined Hepatitis A Virus (Inactivated) and Typhoid Polysaccharide Vaccine Patient Group Direction (PGD) This PGD is for the administration of combined hepatitis A virus (inactivated) and typhoid polysaccharide vaccine (HepA/Typhoid) to individuals considered at risk of exposure to Salmonella enterica serovar typhi, (S. typhi) and hepatitis A virus in accordance with recommendations from the National Travel Health Network and Centre (NaTHNaC). This PGD is for the administration of HepA/Typhoid by registered healthcare practitioners identified in Section 3, subject to any limitations to authorisation detailed in Section 2. Reference no: HepA/Typhoid vaccine PGD Version no: V02.00 Valid from: 01 March 2020 Review date: 01 September 2021 Expiry date: 28 February 2022 Public Health England has developed this PGD to facilitate publicly-funded immunisation in line with national recommendations. Those using this PGD must ensure that it is organisationally authorised and signed in Section 2 by an appropriate authorising person, relating to the class of person by whom the product is to be supplied, in accordance with Human Medicines Regulations 2012 (HMR2012)1. The PGD is not legal or valid without signed authorisation in accordance with HMR2012 Schedule 16 Part 2. Authorising organisations must not alter, amend or add to the clinical content of this document (sections 4, 5 and 6); such action will invalidate the clinical sign-off with which it is provided. In addition authorising organisations must not alter section 3 ‘Characteristics of staff’. Only sections 2 and 7 can be amended within the designated editable fields provided. Operation of this PGD is the responsibility of commissioners and service providers. -

Key Roles of Adjuvants in Modern Vaccines

R E V I E W Key roles of adjuvants in modern vaccines Steven G Reed, Mark T Orr & Christopher B Fox Vaccines containing novel adjuvant formulations are increasingly reaching advanced development and licensing stages, providing new tools to fill previously unmet clinical needs. However, many adjuvants fail during product development owing to factors such as manufacturability, stability, lack of effectiveness, unacceptable levels of tolerability or safety concerns. This Review outlines the potential benefits of adjuvants in current and future vaccines and describes the importance of formulation and mechanisms of action of adjuvants. Moreover, we emphasize safety considerations and other crucial aspects in the clinical development of effective adjuvants that will help facilitate effective next-generation vaccines against devastating infectious diseases. Adjuvants have proven to be key components in vaccines that are Modern adjuvant development, which in spite of many hurdles is today taken for granted. Indeed, many vaccines, comprised of whole or progressing, is based on enhancing and shaping vaccine-induced killed bacteria or viruses, have inherent immune-potentiating activity. responses without compromising safety by selectively adding well- However, attempts to develop a new generation of adjuvants, which defined molecules, formulations or both. Because vaccines are often will be essential for new vaccines, have been hindered somewhat by employed prophylactically in populations of very young people, it perceived, but most often undocumented, health risks and public is important that medical risks to the subject (that is, safety) and misinformation, rather than by verified safety issues. Nonetheless, it other adverse effects (that is, tolerability) are addressed. Vaccine is essential that vaccine and adjuvant developers fully utilize infor- adjuvants designed for therapeutic uses, such as in cancer, may mation on adjuvants’ modes of action, avoid using undefined com- have a different risk-benefit profile. -

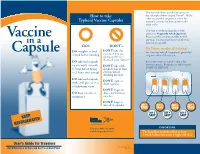

How to Take Typhoid Vaccine Capsules

Your travel medicine provider has given you How to take the oral typhoid fever vaccine, Vivotif ®. Unlike other vaccines that are given as a shot, this Typhoid Vaccine Capsules vaccine is contained in four capsules and is taken orally. This easy-to-understand guide provides answers to Frequently Asked Questions. Vaccine Please read this handout carefully. As with any drug, it is important that you follow the in a instructions carefully. DO’s DON’T’s Do I have to take all 4 doses? DO complete at least Don’T take the Capsule vaccine if you are Yes. You must take all 4 capsules to get the full 1 week before traveling taking antibiotics long term effect of the vaccine. (Consult your doctor) DO take each capsule Just as important, you need to skip a day on an empty stomach Don’T take with between capsules. Remember to take a capsule (1 hour before eating alcohol (wait at least EVERY OTHER DAY. or 2 hours after eating) 2 hours before drinking alcohol) DO take each capsule DON’T open or with a full glass of cool chew capsules or lukewarm water Don’T forget to DO keep capsules in skip a day between refrigerator capsules Don’T forget to take all 4 capsules DAY 1 DAY 3 DAY 5 DAY 7 TAKE TAKE TAKE TAKE DAY 2 DAY 4 DAY 6 KEEP SKIP SKIP SKIP REFRIGERATED Telephone 800-533-5899 IMPORtaNT www.bernaproducts.com The last dose must be taken at least 1 week before you enter a high-risk area User’s Guide for Travelers COT-V23-VIC (1/06) Quick Reference for Do’s and Don’t’s on Back Panel RV (1/07) How does the oral typhoid Do I have to take the capsule fever vaccine work? with water? Yes. -

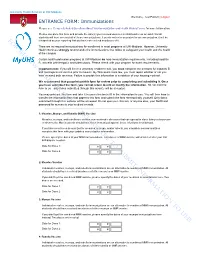

Do Not Use to Submit Information To

University Health Services at UW-Madison Welcome, Test Patient | Logout ENTRANCE FORM: Immunizations Please see Frequently Asked Questions About Your Immunization and Health History Forms for more information. Please complete this form and provide the date(s) you received vaccines in childhood or as an adult. Not all students will have received all of these immunizations. If you do not enter any dates for an immunization, it will be For interpreted as your reporting that you have not received any doses of it. There are no required immunizations for enrollment in most programs at UW-Madison. However, University review Health Services strongly recommends the immunizations that follow to safeguard your health and the health of the campus. Certain health profession programs at UW-Madison do have immunization requirements, including hepatitis B, varicella (chickenpox), and tuberculosis. Please check with your program for exact requirements. purposesImportant note: If you will live in a university residence hall, you must complete the sections for hepatitis B and meningococcal vaccine prior to move-in. By Wisconsin state law, you must report whether or not you have received both vaccines. Failure to provide this information is a violation of your housing contract. We recommend that you print out this form for review prior to completing and submitting it. Once you have submitted the form, you cannot return to add or modify the information. Do not mail the form to us—only forms submitted through this website will be accepted. You may print out onlythis form and take it to your clinician to fill in the information for you. -

TYPHOID VACCINE 20, Avenue Appia, CH-1211 Geneva 27 Switzerland S & Health Product April 2014

INFORMATION SHEET OBSERVED RATE OF VACCINE REACTIONS Global Vaccine Safety Essential Medicines & Health Products TYPHOID VACCINE 20, Avenue Appia, CH-1211 Geneva 27 Switzerland s & Health Product April 2014 20, avenue Appia, Ch-1211 Geneva 27 The Vaccines Several typhoid vaccines are currently available and these can be administered orally or parenterally and are safe and efficacious for preventing typhoid fever (Fraser et al, 2007, see Table 1). Adverse events are mild in nature. Oral vaccine Live attenuated vaccine: (Ty21a) (Vivotif TM, Berna Biotech, Crucell; Zerotyph caps, Boryung). This vaccine was developed in the early 1970s, requires at least three doses for optimal protection, and is supplied as gelatin capsules coated with phthalate or sachets containing lyophilised Ty21a, a mutant strain of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi (S. Typhi). Parenteral vaccines Monovalent typhoid vaccines: Vi polysaccharide is a well-standardized antigen that is effective in a single parenteral dose, is safer than whole-cell vaccine, and may be used in children 2 years of age or older (Plotkin and Bouveret-LeCam, 1995). The following vaccines contain the Vi antigen. Capsular polysaccharide vaccines: (ViCPS) (TypherixTM, GSK; Typhim ViTM, Sanofi Pasteur; TypBar, Bharat Biotech; Shantyph, Shanta Biotech; Typho-Vi, BioMed; Zerotyph inj, Boryung, South Korea; Typhevac-inj, Shanghai Institute of Biological Products) is a one-dose injectable solution consisting 25 µg Vi antigen prepared from the surface polysaccharide of S. Typhi strain Ty2. Conjugate vaccine: (Vi-TT), where the Vi antigen is coupled to a carrier protein. At the time of review there is only one licensed conjugate vaccine (Peda-typhTM, BioMed). It consists of Vi coupled to tetanus toxoid (TT). -

Revised Recommendations for the Administration of More Than One Live Vaccine

Revised recommendations for the administration of more than one live vaccine Introduction For many years, Immunisation against Infectious Disease (the Green Book) has contained a recommendation that when two live vaccines are required in the same individual, then the vaccines should either be given on the same day, or separated by an interval of at least four weeks. This was based on early studies with measles and smallpox vaccines,1 and supported by the theory that interferon production stimulated by the replication of first vaccine prevented replication of the second agent, thus leading to a poor response to the second vaccine. Following the recent introduction into the routine schedule of two live vaccines not given by a parenteral route (live attenuated nasal influenza vaccine and oral rotavirus vaccine) the evidence to support this general recommendation was reviewed. Based upon the available evidence and on the different immune mechanisms used by the various vaccines, in February 2014 the JCVI 2 agreed that the guidance to either administer the vaccines on the same day or at four week interval period was not generalizable to all live vaccines. They concluded therefore, that intervals between vaccines should be based only upon specific evidence for any interference of those vaccines. Therefore, to ensure protection from live vaccines is offered to individuals in a timely manner, the JCVI agreed that the current immunisation guidance should be updated to reflect this change. 1 Petralli JK, Merigan TC, Wilbur JR. Action of endogenous interferon against vaccinia infection in children. Lancet 1965;286(7409):401-405. 2 Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) 2014.