Evidence-Based Guidelines for Treating Bipolar Disorder 347

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iii. Administración Local

BOCM BOLETÍN OFICIAL DE LA COMUNIDAD DE MADRID Pág. 468 LUNES 21 DE MARZO DE 2011 B.O.C.M. Núm. 67 III. ADMINISTRACIÓN LOCAL AYUNTAMIENTO DE 17 MADRID RÉGIMEN ECONÓMICO Agencia Tributaria Madrid Subdirección General de Recaudación En los expedientes que se tramitan en esta Subdirección General de Recaudación con- forme al procedimiento de apremio, se ha intentado la notificación cuya clave se indica en la columna “TN”, sin que haya podido practicarse por causas no imputables a esta Administra- ción. Al amparo de lo dispuesto en el artículo 112 de la Ley 58/2003, de 17 de diciembre, Ge- neral Tributaria (“Boletín Oficial del Estado” número 302, de 18 de diciembre), por el presen- te anuncio se emplaza a los interesados que se consignan en el anexo adjunto, a fin de que comparezcan ante el Órgano y Oficina Municipal que se especifica en el mismo, con el obje- to de serles entregada la respectiva notificación. A tal efecto, se les señala que deberán comparecer en cualquiera de las Oficinas de Atención Integral al Contribuyente, dentro del plazo de los quince días naturales al de la pu- blicación del presente anuncio en el BOLETÍN OFICIAL DE LA COMUNIDAD DE MADRID, de lunes a jueves, entre las nueve y las diecisiete horas, y los viernes y el mes de agosto, entre las nueve y las catorce horas. Quedan advertidos de que, transcurrido dicho plazo sin que tuviere lugar su compare- cencia, se entenderá producida la notificación a todos los efectos legales desde el día si- guiente al del vencimiento del plazo señalado. -

Surname Folders.Pdf

SURNAME Where Filed Aaron Filed under "A" Misc folder Andrick Abdon Filed under "A" Misc folder Angeny Abel Anger Filed under "A" Misc folder Aberts Angst Filed under "A" Misc folder Abram Angstadt Achey Ankrum Filed under "A" Misc folder Acker Anns Ackerman Annveg Filed under “A” Misc folder Adair Ansel Adam Anspach Adams Anthony Addleman Appenzeller Ader Filed under "A" Misc folder Apple/Appel Adkins Filed under "A" Misc folder Applebach Aduddell Filed under “A” Misc folder Appleman Aeder Appler Ainsworth Apps/Upps Filed under "A" Misc folder Aitken Filed under "A" Misc folder Apt Filed under "A" Misc folder Akers Filed under "A" Misc folder Arbogast Filed under "A" Misc folder Albaugh Filed under "A" Misc folder Archer Filed under "A" Misc folder Alberson Filed under “A” Misc folder Arment Albert Armentrout Albight/Albrecht Armistead Alcorn Armitradinge Alden Filed under "A" Misc folder Armour Alderfer Armstrong Alexander Arndt Alger Arnold Allebach Arnsberger Filed under "A" Misc folder Alleman Arrel Filed under "A" Misc folder Allen Arritt/Erret Filed under “A” Misc folder Allender Filed under "A" Misc folder Aschliman/Ashelman Allgyer Ash Filed under “A” Misc folder Allison Ashenfelter Filed under "A" Misc folder Allumbaugh Filed under "A" Misc folder Ashoff Alspach Asper Filed under "A" Misc folder Alstadt Aspinwall Filed under "A" Misc folder Alt Aston Filed under "A" Misc folder Alter Atiyeh Filed under "A" Misc folder Althaus Atkins Filed under "A" Misc folder Altland Atkinson Alwine Atticks Amalong Atwell Amborn Filed under -

![Arxiv:1810.00224V2 [Q-Bio.PE] 7 Dec 2020 Humanity Is Increasingly Influencing Global Environments [195]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3556/arxiv-1810-00224v2-q-bio-pe-7-dec-2020-humanity-is-increasingly-in-uencing-global-environments-195-943556.webp)

Arxiv:1810.00224V2 [Q-Bio.PE] 7 Dec 2020 Humanity Is Increasingly Influencing Global Environments [195]

A Survey of Biodiversity Informatics: Concepts, Practices, and Challenges Luiz M. R. Gadelha Jr.1* Pedro C. de Siracusa1 Artur Ziviani1 Eduardo Couto Dalcin2 Helen Michelle Affe2 Marinez Ferreira de Siqueira2 Luís Alexandre Estevão da Silva2 Douglas A. Augusto3 Eduardo Krempser3 Marcia Chame3 Raquel Lopes Costa4 Pedro Milet Meirelles5 and Fabiano Thompson6 1National Laboratory for Scientific Computing, Petrópolis, Brazil 2Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena, Jena, Germany 2Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 3Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 4National Institute of Cancer, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 5Federal University of Bahia, Salvador, Brazil 6Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Abstract The unprecedented size of the human population, along with its associated economic activities, have an ever increasing impact on global environments. Across the world, countries are concerned about the growing resource consumption and the capacity of ecosystems to provide them. To effectively conserve biodiversity, it is essential to make indicators and knowledge openly available to decision-makers in ways that they can effectively use them. The development and deployment of mechanisms to produce these indicators depend on having access to trustworthy data from field surveys and automated sensors, biological collections, molec- ular data, and historic academic literature. The transformation of this raw data into synthesized information that is fit for use requires going through many refinement steps. The methodologies and techniques used to manage and analyze this data comprise an area often called biodiversity informatics (or e-Biodiversity). Bio- diversity data follows a life cycle consisting of planning, collection, certification, description, preservation, discovery, integration, and analysis. -

Most-Common-Surnames-Bmd-Registers-16.Pdf

Most Common Surnames Surnames occurring most often in Scotland's registers of Births, Marriages and Deaths Counting only the surname of the child for births, the surnames of BOTH PARTIES (for example both BRIDE and GROOM) for marriages, and the surname of the deceased for deaths Note: the surnames from these registers may not be representative of the surnames of the population of Scotland as a whole, as (a) they include the surnames of non-residents who were born / married / died here; (b) they exclude the surnames of residents who were born / married / died elsewhere; and (c) some age-groups have very low birth, marriage and death rates; others account for most births, marriages and deaths.ths Registration Year = 2016 Position Surname Number 1 SMITH 2056 2 BROWN 1435 3 WILSON 1354 4 CAMPBELL 1147 5 STEWART 1139 6 THOMSON 1127 7 ROBERTSON 1088 8 ANDERSON 1001 9 MACDONALD 808 10 TAYLOR 782 11 SCOTT 771 12 REID 755 13 MURRAY 754 14 CLARK 734 15 WATSON 642 16 ROSS 629 17 YOUNG 608 18 MITCHELL 601 19 WALKER 589 20= MORRISON 587 20= PATERSON 587 22 GRAHAM 569 23 HAMILTON 541 24 FRASER 529 25 MARTIN 528 26 GRAY 523 27 HENDERSON 522 28 KERR 521 29 MCDONALD 520 30 FERGUSON 513 31 MILLER 511 32 CAMERON 510 33= DAVIDSON 506 33= JOHNSTON 506 35 BELL 483 36 KELLY 478 37 DUNCAN 473 38 HUNTER 450 39 SIMPSON 438 40 MACLEOD 435 41 MACKENZIE 434 42 ALLAN 432 43 GRANT 429 44 WALLACE 401 45 BLACK 399 © Crown Copyright 2017 46 RUSSELL 394 47 JONES 392 48 MACKAY 372 49= MARSHALL 370 49= SUTHERLAND 370 51 WRIGHT 357 52 GIBSON 356 53 BURNS 353 54= KENNEDY 347 -

Boletín Oficial

Boletín Oficial de la provincia de Sevilla Publicación diaria, excepto festivos Depósito Legal SE–1–1958 Martes 29 de marzo de 2011 Número 72 T.G.S.S. 022 SUPLEMENTO NÚM. 17 Sumario DELEGACIÓN DEL GOBIERNO EN ANDALUCÍA: — Subdelegación del Gobierno en Sevilla: Notificaciones . 2 JUNTA DE ANDALUCÍA: — Consejería de Empleo: Delegación Provincial de Sevilla: Tablas salariales del Convenio Colectivo de la empresa Kraft Foods Production, S.L.U., del Centro de Trabajo de Dos Her- manas (Sevilla), para los años 2010, 2011 y 2012 (Revisión y Garantía Salariales) . 5 Convenio Colectivo de la empresa Fundación para el Desarro- llo Agroalimentario, con vigencia desde su publicación al 30 de junio de 2013. 8 TESORERÍA GENERAL DE LA SEGURIDAD SOCIAL: — Dirección Provincial de Sevilla: Subdirección Provincial de Gestión Recaudatoria: Notificaciones . 25 Subdirección Provincial de Procedimientos Especiales: Notificaciones . 55 Administraciones números 41/01, 41/02, 41/04, 41/05, 41/06, 41/08 y 41/10: Notificaciones . 55 Unidades de Recaudación Ejecutiva 41/05, 41/06, 41/07, 41/09 y 41/10: Notificaciones . 61 — Dirección Provincial de Almería: Unidades de Recaudación Ejecutiva 04/04 y 10: Notificaciones . 82 — Dirección Provincial de Cádiz: Administración de Jerez de la Frontera: Notificaciones . 85 Unidad de Impugnaciones: Notificación . 86 — Dirección Provincial de Córdoba: Unidad de Recaudación Ejecutiva 14/05: Notificaciones . 86 Unidad de Impugnaciones: Notificación . 88 — Dirección Provincial de Huelva: Unidad de Recaudación Ejecutiva 21/01: Notificaciones . 89 — Dirección Provincial de Málaga: Unidad de Recaudación Ejecutiva 29/09 de Estepona: Notificación . 90 — Dirección Provincial de Vizcaya: Notificaciones . 91 INSPECCIÓN PROVINCIAL DE TRABAJO Y SEGURIDAD SOCIAL DE SEVILLA: Notificaciones de actas de infracción . -

Exploration, Disruption, Diaspora: Movement of Nuevomexicanos to Utah, 1776-1850 Linda C

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository American Studies ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-11-2019 Exploration, Disruption, Diaspora: Movement of Nuevomexicanos to Utah, 1776-1850 Linda C. Eleshuk Roybal Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Eleshuk Roybal, Linda C.. "Exploration, Disruption, Diaspora: Movement of Nuevomexicanos to Utah, 1776-1850." (2019). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds/80 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Linda Catherine Eleshuk Roybal Candidate American Studies Department This dissertation is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: A.Gabriel Meléndez, Chair Kathleen Holscher Michelle Hall Kells Enrique Lamadrid i Exploration, Disruption, Diaspora: Movement Of Nuevomexicanos to Utah, 1776 – 1950 By Linda Catherine Eleshuk Roybal B.S. Psychology, Weber State College, 1973 B.S. Communications, Weber State University, 1982 M.S. English, Utah State University, 1997 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In American Studies The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May 2019 ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my children and grandchildren, born and yet to be — Joys of my life and ambassadors to a future I will not see, Con mucho cariño. iii Acknowledgements I am grateful to so many people who have shared their expertise and resources to bring this project to its completion. -

Momsrising HUD Book.Pdf

Assistant Secretary for Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity John Trasviña U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 451 7th Street S.W., Washington, DC 20410 Dear Assistant Secretary Trasviña, As you know all too well, there’s hardly a need more basic than shelter for our families. And when trying to rent or buy a home, everyone should get a fair shake. Unfortunately, many women and families in search of a home do not know their rights. And many lenders and landlords who figuratively – or even literally – “hold the keys” to a family’s new home are either ignorant of the laws prohibiting discrimination against mothers and families or worse, willfully disobeying them. All too often, mothers are discriminated against in our country in terms of hiring and wages, and housing dis- crimination on the basis of familial status are equally illegal and unacceptable. Your commitment to fighting this discrimination is an inspiration and MomsRising and our more than one mil- lion members (including mother, fathers, grandparents and guardians working to achieve economic security for American families) are proud to have partnered with you in that effort. In the last several months, MomsRising has heard from many credit-worthy pregnant women and mothers across the country who are being denied home loans or rentals apartments solely because they are on maternity leave or have children. You will find a selection of these heartbreaking and infuriating stories in this booklet. The members of MomsRising applaud HUD for your groundbreaking work to end housing discrimination against pregnant women and mothers. This booklet contains the names of over 14,000 mothers and their allies who have signed on to thank HUD and to urge the agency to continue to vigorously enforce fair housing laws as relates to mothers who seek to rent or buy a home. -

Bdo International Directory 2017

International Directory 2017 Latest version updated 5 July 2017 1 ABOUT BDO BDO is an international network of public accounting, tax and advisory firms, the BDO Member Firms, which perform professional services under the name of BDO. Each BDO Member Firm is a member of BDO International Limited, a UK company limited by guarantee. The BDO network is governed by the Council, the Global Board and the Executive (or Global Leadership Team) of BDO International Limited. Service provision within the BDO network is coordinated by Brussels Worldwide Services BVBA, a limited liability company incorporated in Belgium with VAT/BTW number BE 0820.820.829, RPR Brussels. BDO International Limited and Brussels Worldwide Services BVBA do not provide any professional services to clients. This is the sole preserve of the BDO Member Firms. Each of BDO International Limited, Brussels Worldwide Services BVBA and the member firms of the BDO network is a separate legal entity and has no liability for another such entity’s acts or omissions. Nothing in the arrangements or rules of BDO shall constitute or imply an agency relationship or a partnership between BDO International Limited, Brussels Worldwide Services BVBA and/or the member firms of the BDO network. BDO is the brand name for the BDO network and all BDO Member Firms. BDO is a registered trademark of Stichting BDO. © 2017 Brussels Worldwide Services BVBA 2 2016* World wide fee Income (millions) EUR 6,844 USD 7,601 Number of countries 158 Number of offices 1,401 Partners 5,736 Professional staff 52,486 Administrative staff 9,509 Total staff 67,731 Web site: www.bdointernational.com (provides links to BDO Member Firm web sites world wide) * Figures as per 30 September 2016 including exclusive alliances of BDO Member Firms. -

Commencement2019

FPO UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI COMMENCEMENT2019 MAY 9 • 3 p.m. Graduate Degree Ceremony UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI COMMENCEMENT2019 MAY 9 • 3 p.m. GRADUATE DEGREE CEREMONY Graduate School School of Architecture Business School School of Communication School of Education and Human Development Phillip and Patricia Frost School of Music CommencementCommencement MarshalsProgram Grand Marshal A. Parasuraman, D.B.A. Business School Alumni Association Banner Marshal Larry W. Ingraham, M.B.A. ’83 Faculty Senate Marshal Scotney Evans, Ph.D. School of Education and Human Development Academic Banner Marshals Graduate School Soyeon Ahn, Ph.D. School of Architecture Charles Bohl, Ph.D. Business School Andrea Heuson, Ph.D. School of Communication Diane Millette, Ed.D. School of Education and Human Development Kysha Harriell, Ph.D. Phillip and Patricia Frost School of Music John Daversa, D.M.A. Faculty Marshals School of Architecture Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, M.Arch. Allan Shulman, M.Arch. Business School Patricia Abril, J.D. Diana Falsetta, Ph.D. Doug Lehmann, Ph.D. Jeffrey Weinstock, M.B.A. Tallys Yunes, Ph.D. School of Communication Grace Barnes, M.F.A. Paul Driscoll, Ph.D. Victoria Orrego Dunleavy, Ph.D. Juliana Fernandes, Ph.D. School of Education and Human Development Batya Elbaum, Ph.D. Blaine Fowers, Ph.D. Walter Secada, Ph.D. Warren Whisenant, Ph.D. Phillip and Patricia Frost School of Music Shannon de l’Etoile, Ph.D. Serona Elton, J.D. Trudy Kane, M.M. Gary Keller, M.M. 2 Commencement Program Hooders Juan Chattah, Ph.D. Phillip and Patricia Frost School of Music Barbara Millet, Ph.D. School of Communication Alumni Marshals Harold Long Jr., A.B. -

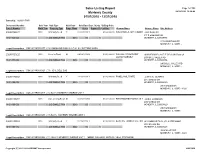

Sales Report

Sales Listing Report Page 1 of 305 McHenry County 04/23/2019 12:20:49 01/01/2018 - 12/31/2018 Township: NUNDA TWP Document Number Sale Year Sale Type Valid Sale Sale Date Dept. Study Selling Price Parcel Number Built Year Property Type Prop. Class Acres Square Ft. Lot Size Grantor Name Grantee Name Site Address 2018R0023177 2018 Warranty Deed Y 07/02/2018 Y $160,000.00 WIN DANIELS AMY HUMBRACHTJAKE FOWLER 317 S EMERALD DR 14-01-126-023 0040 RES W/BLDG0 SINGLE FAM 0040 .00 0 MCHENRY, IL 600519375 317 S EMERALD DR MCHENRY, IL 60051 - Legal Description: DOC 2018R0023177 LT 24 EMERALD PARK & LT 24 R J SUTTONS ADDN 2018R0030125 2018 Deed in Trust N 08/29/2018 N $200,000.00 WILLIAM SCHMIEGELT SHIRLEY MAE CASTLE DECLARATION OF TRUST LUZ SCHMIEGELT 2900 BULL VALLEY RD 14-01-153-008 0040 RES W/BLDG0 SINGLE FAM 0040 .00 0 MCHENRY, IL 600508356 2900 BULL VALLEY RD MCHENRY, IL 60050 - Legal Description: DOC 2018R0030125 LT 6 IDYL DELL SUB 2018R0042818 2018 Warranty Deed Y 12/17/2018 Y $270,000.00 PAMELA MILITANTE JUSTIN D. MURPHY 2913 GREGG DR 14-01-305-003 0040 RES W/BLDG0 SINGLE FAM 0040 .00 0 MCHENRY, IL 600508320 2913 GREGG DR MCHENRY, IL 60050 -8320 Legal Description: DOC 2018R0042818 LT 2 BLK 6 MCHENRY SHORES UNIT 1 2018R0023257 2018 Sale among RelativesN 06/20/2018 N $137,500.00 FIRST MIDWEST BANK AS TRUSTEEJAMES HUMBARD 2907 GREGG DR 14-01-305-006 0040 RES W/BLDG0 SINGLE FAM 0040 .00 0 MCHENRY, IL 600508320 2907 GREGG DR MCHENRY, IL 60050 Legal Description: DOC 2018R0023257 LT 5 BLK 6 MCHENRY SHORES UNIT 1 2018R0023902 2018 Warranty Deed -

2011 Public Sector Salary Disclosure

Disclosure for 2011 under the Public Sector Salary Disclosure Act, 1996 Hospitals and Boards of Public Health This category includes Ontario Hospitals and Boards of Public Health. Some Boards of Public Health can be found under a municipality in the “Municipalities and Services” category. Divulgation pour 2011 en vertu de la Loi de 1996 sur la divulgation des traitements dans le secteur public Hôpitaux et Conseils de santé Cette catégorie contient les hôpitaux de l’Ontario et les Conseils de santé. Il se peut que certains Conseils de santé soient inclus dans la divulgation d’une municipalité dans la catégorie «Municipalités et services». Taxable Surname/Nom de Given Name/ Salary Paid/ Benefits/ Employer/Employeur famille Prénom Position/Poste Traitement Avant. impos. Alexandra Hospital, Ingersoll GARDNER LISA ANNE Director, Patient Services/Chief Nursing Officer$104,352.15 $793.45 Alexandra Hospital, Ingersoll JOANNE ACKERT Registered Nurse $100,982.19 $628.30 Alexandra Marine & General Hospital BEDARD RICHARD Chief Information Officer / Director Clinical Support$107,074.62 $604.56 Alexandra Marine & General Hospital MCGILLIVRAY SUSAN Chief Financial Officer / Director Human Resources$103,691.62 $586.26 Alexandra Marine & General Hospital TAYLOR CHERYL Director of Patient Services / Chief Nursing Executive$122,401.62 $692.16 Alexandra Marine & General Hospital THIBERT WILLIAM President / Chief Executive Officer$121,939.55 $163.40 Almonte General Hospital BLACKBURN RUBY Registered Nurse $103,179.27 $0.00 Almonte General Hospital LEAFLOOR -

Banking Act Unclaimed Money As at 31 December 2007

Commonwealth of Australia Gazette No. ASIC 40A/08, Wednesday, 21 May 2008 Published by ASIC ASIC Gazette Contents Banking Act Unclaimed Money as at 31 December 2007 RIGHTS OF REVIEW Persons affected by certain decisions made by ASIC under the Corporations Act 2001 and the other legislation administered by ASIC may have rights of review. ASIC has published Regulatory Guide 57 Notification of rights of review (RG57) and Information Sheet ASIC decisions – your rights (INFO 9) to assist you to determine whether you have a right of review. You can obtain a copy of these documents from the ASIC Digest, the ASIC website at www.asic.gov.au or from the Administrative Law Co-ordinator in the ASIC office with which you have been dealing. ISSN 1445-6060 (Online version) Available from www.asic.gov.au ISSN 1445-6079 (CD-ROM version) Email [email protected] © Commonwealth of Australia, 2008 This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all rights are reserved. Requests for authorisation to reproduce, publish or communicate this work should be made to: Gazette Publisher, Australian Securities and Investment Commission, GPO Box 9827, Melbourne Vic 3001 ASIC GAZETTE Commonwealth of Australia Gazette ASIC 40A/08, Wednesday, 21 May 2008 Banking Act Unclaimed Money Page 2 of 463 Specific disclaimer for Special Gazette relating to Banking Unclaimed Monies The information in this Gazette is provided by Authorised Deposit-taking Institutions to ASIC pursuant to the Banking Act (Commonwealth) 1959. The information is published by ASIC as supplied by the relevant Authorised Deposit-taking Institution and ASIC does not add to the information.