Family Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major Trends Affecting Families in Central America and the Caribbean

Major Trends Affecting Families in Central America and the Caribbean Prepared by: Dr. Godfrey St. Bernard The University of the West Indies St. Augustine Trinidad and Tobago Phone Contacts: 1-868-776-4768 (mobile) 1-868-640-5584 (home) 1-868-662-2002 ext. 2148 (office) E-mail Contacts: [email protected] [email protected] Prepared for: United Nations Division of Social Policy and Development Department of Economic and Social Affairs Program on the Family Date: May 23, 2003 Introduction Though an elusive concept, the family is a social institution that binds two or more individuals into a primary group to the extent that the members of the group are related to one another on the basis of blood relationships, affinity or some other symbolic network of association. It is an essential pillar upon which all societies are built and with such a character, has transcended time and space. Often times, it has been mooted that the most constant thing in life is change, a phenomenon that is characteristic of the family irrespective of space and time. The dynamic character of family structures, - including members’ status, their associated roles, functions and interpersonal relationships, - has an important impact on a host of other social institutional spheres, prospective economic fortunes, political decision-making and sustainable futures. Assuming that the ultimate goal of all societies is to enhance quality of life, the family constitutes a worthy unit of inquiry. Whether from a social or economic standpoint, the family is critical in stimulating the well being of a people. The family has been and will continue to be subjected to myriad social, economic, cultural, political and environmental forces that shape it. -

How Understanding the Aboriginal Kinship System Can Inform Better

How understanding the Aboriginal Kinship system can inform better policy and practice: social work research with the Larrakia and Warumungu Peoples of the Northern Territory Submitted by KAREN CHRISTINE KING BSW A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Social Work Faculty of Arts and Science Australian Catholic University December 2011 2 STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP AND SOURCES This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No other person‟s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. All research procedures reported in the thesis received the approval of the Australian Catholic University Human Research Ethics Committee. Karen Christine King BSW 9th March 2012 3 4 ABSTRACT This qualitative inquiry explored the kinship system of both the Larrakia and Warumungu peoples of the Northern Territory with the aim of informing social work theory and practice in Australia. It also aimed to return information to the knowledge holders for the purposes of strengthening Aboriginal ways of knowing, being and doing. This study is presented as a journey, with the oral story-telling traditions of the Larrakia and Warumungu embedded and laced throughout. The kinship system is unpacked in detail, and knowledge holders explain its benefits in their lives along with their support for sharing this knowledge with social workers. -

Family: Variations and Changes Across Cultures James Georgas the University of Athens, Greece, [email protected]

Unit 6 Developmental Psychology and Culture Article 3 Subunit 3 Cultural Perspectives on Families 8-1-2003 Family: Variations and Changes Across Cultures James Georgas The University of Athens, Greece, [email protected] Recommended Citation Georgas, J. (2003). Family: Variations and Changes Across Cultures. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 6(3). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1061 This Online Readings in Psychology and Culture Article is brought to you for free and open access (provided uses are educational in nature)by IACCP and ScholarWorks@GVSU. Copyright © 2003 International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology. All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-0-9845627-0-1 Family: Variations and Changes Across Cultures Abstract In order to study psychological phenomena cross-culturally, it is necessary to understand the different types of family in cultures throughout the world and also how family types are related to cultural features of societies. This article discusses: The definitions and the structure and functions of family; the different family types and relationships with kin; the ecocultural determinants of variations of family types, e.g, ecological features, means of subsistence, political and legal system, education and religion; changes in family in different cultures; the influence of modernization and globalization on family change throughout the world. Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. This article is available in Online Readings in Psychology and Culture: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/orpc/vol6/iss3/3 Georgas: Family: Variations and Changes Across Cultures Introduction It is common knowledge that cultures seem to have different types of family systems. -

An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies

11 Close–Distant: An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies Abstract This chapter looks at the evidence for the close–distant dichotomy in the kinship systems of Australian Aboriginal societies. The close– distant dichotomy operates on two levels. It is the distinction familiar to Westerners from their own culture between close and distant relatives: those we have frequent contact with as opposed to those we know about but rarely, or never, see. In Aboriginal societies, there is a further distinction: those with whom we share our quotidian existence, and those who live at some physical distance, with whom we feel a social and cultural commonality, but also a decided sense of difference. This chapter gathers a substantial body of evidence to indicate that distance, both physical and genealogical, is a conception intrinsic to the Indigenous understanding of the function and purpose of kinship systems. Having done so, it explores the implications of the close–distant dichotomy for the understanding of pre-European Aboriginal societies in general—in other words: if the dichotomy is a key factor in how Indigenes structure their society, what does it say about the limits and integrity of the societies that employ that kinship system? 363 SKIN, KIN AND CLAN Introduction Kinship is synonymous with anthropology. Morgan’s (1871) Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family is one of the founding documents of the discipline. It also has an immediate connection to Australia: one of the first fieldworkers to assist Morgan in gathering his data was Lorimer Fison, who, later joined by A. -

Third Degree of Consanguinity

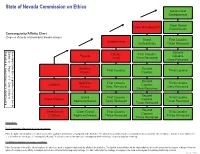

State of Nevada Commission on Ethics Great-Great Grandparents 4 Great Grand Great Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Consanguinity/Affinity Chart 3 5 (Degrees of family relationship by blood/marriage) Grand First Cousins Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Twice Removed 2 4 6 Second Uncles First Cousins Parents Cousins Aunts Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 Brothers Second First Cousins Third Cousins Sisters Cousins 2 4 6 8 Second Nephews First Cousins Third Cousins Children Cousins Nieces Once Removed Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 9 Second Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Grand Children Cousins Nephews/Nieces Twice Removed Twice Removed 1 2 4 6 Twice Removed 8 0 Second Great Grand Great Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Cousins Children Nephews/Nieces Thrice Removed Thrice Removed 1 3 5 7 Thrice Removed 9 1 Instructions: For Consanguinity (relationship by blood) calculations: Place the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by consanguinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the public officer/employee. Anyone in a box numbered 1, 2, or 3 is within the third degree of consanguinity. Nevada Ethics in Government Law addresses consanguinity within third degree by blood, adoption or marriage. For Affinity (relationship by marriage) calculations: Place the spouse of the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by affinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the spouse and the degree of distance from the public officer/employee by affinity. A husband and wife are related in the first degree by marriage. -

The Joking Relationship and Kinship: Charting a Theoretical Dependency

JASO 24/3 (1993): 251-263 THE JOKING RELATIONSHIP AND KINSHIP: CHARTING A THEORETICAL DEPENDENCY ROBERT PARKIN ALTHOUGH the anthropology of jokes and of humour generally is a relatively new phenomenon (see, for example, Apte 1985)" the anthropology of joking has a long history. It has been taken up at some point or another by most of the main theoreticians of the subject and their treatment of it often serves to characterize their general approach; moreover, there can be few anthropologists who have not enoountered it and had to deal with it in the field. What has stimulated anthropologists is the fact that societies are almost invariably internally differentiated in some way and that one does not joke with everyone. The very fact that joking has to involve at least two people ensures its social character, while the requirement not to joke is equally obviously a social injunction. The questions anthropologists have asked themselves are, why the difference, and how is it manifested in any particular society? This is a revised version of a paper first given on 26 June 1989 at the Institut fUr Ethnologie, Freie UniversiUit Berlin, in a seminar series chaired by Dr Burkhard Schnepel and entitled 'The Fool in Social Anthropological Perspective'. A German version was presented subsequently at the Deutsche Gesellschaft filr VOlkerkunde conference in Munich on 18 October 1991 and is to be published in due course in a book edited by Dr Schnepel and Dr Michael Kuper. In the present version certain aspects of the material argument have been modified, though the style of the original oral delivery has been left largely untouched. -

1 Childhood Within Anthropology

9781405125901_4_001.qxd 5/6/08 5:08 PM Page 17 1 CHILDHOOD WITHIN ANTHROPOLOGY Introduction Looking back on the ways that children and childhood have been ana- lyzed in anthropology inevitably reveals gaps, but it also shows that anthro- pologists have a long history of studying children. This chapter will give an overview of several schools of anthropological thinking that have considered children and used ideas about childhood to contribute to holistic understandings of culture. It will examine how anthropologists have studied children in the past and what insights these studies can bring to more recent analyses. Although not always explicit, ideas about children, childhood, and the processes by which a child becomes a fully socialized human being are embedded in much anthropological work and are central to understanding the nature of childhood in any given society. Work on child-rearing has also illuminated many aspects of children’s lives and is vital to understanding children themselves and their wider social relationships. Having discussed these, this chapter will then turn to newer studies of childhood, based around child-centered, or child-focused, anthropology with the assumption that children themselves are the best informants about their own lives. This has been presented as a radical break with the ways that anthropologists have studied children previously, when, as Helen Schwartzman has argued, anthropologists “used children as a population of ‘others’ to facilitate the investigation of a range of topics, from developing racial typologies to investigat[ing] acculturation, but they have rarely been perceived as a legitimate topic of research in their own right” (2001:15, emphasis in original). -

The Self: a Transpersonal Neuroanthropological Account

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 32 | Issue 1 Article 10 1-1-2013 The elS f: A Transpersonal Neuroanthropological Account Charles D. Laughlin Carleton University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Anthropology Commons, Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Laughlin, C. D. (2013). Laughlin, C. D. (2013). The es lf: A transpersonal neuroanthropological account. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 32(1), 100–116.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 32 (1). http://dx.doi.org/10.24972/ ijts.2013.32.1.100 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Special Topic Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Self: A Transpersonal Neuroanthropological Account Charles D. Laughlin Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario, Canada The anthropology of the self has gained momentum recently and has produced a significant body of research relevant to interdisciplinary transpersonal studies. The notion of self has broadened from the narrow focus on cultural and linguistic labels for self-related terms, such as person, ego, identity, soul, and so forth, to a realization that the self is a vast system that mediates all the aspects of personality. This shift in emphasis has brought anthropological notions of the self into closer accord with what is known about how the brain mediates self-as-psyche. -

02 Social Cultural Anthropology Module : 16 Kinship: Definition and Approaches

Paper No. : 02 Social Cultural Anthropology Module : 16 Kinship: Definition and Approaches Development Team Principal Investigator Prof. Anup Kumar Kapoor Department of Anthropology, University of Delhi Paper Coordinator Prof. Sabita, Department of Anthropology, Utkal University, Bhubaneshwar Gulsan Khatoon, Department of Anthropology, Utkal Content Writer University, Bhubaneswar Prof. A.K. Sinha, Department of Anthropology, Content Reviewer P anjab University, Chandigarh 1 Social Cultural Anthropology Anthropology Kinship: Definition and Approaches Description of Module Subject Name Anthropology Paper Name 02 Social Cultural Anthropology Module Name/Title Kinship: Definition and Approaches Module Id 16 2 Social Cultural Anthropology Anthropology Kinship: Definition and Approaches Contents Introduction 1. History of kinship study 2. Meaning and definition 3. Kinship approaches 3.1 Structure of Kinship Roles 3.2 Kinship Terminologies 3.3 Kinship Usages 3.4 Rules of Descent 3.5 Descent Group 4. Uniqueness of kinship in anthropology Anthropological symbols for kin Summary Learning outcomes After studying this module: You shall be able to understand the discovery, history and structure of kinship system You will learn the nature of kinship and the genealogical basis of society You will learn about the different approaches of kinship, kinship terminology, kinship usages, rules of descent, etc You will be able to understand the importance of kinship while conducting fieldwork. The primary objective of this module is: 3 Social Cultural Anthropology Anthropology Kinship: Definition and Approaches To give a basic understanding to the students about Kinship, its history of origin, and subject matter It also attempts to provide an informative background about the different Kinship approaches. 4 Social Cultural Anthropology Anthropology Kinship: Definition and Approaches INTRODUCTION The word “kinship” has been used to mean several things-indeed; the situation is so complex that it is necessary to simplify it in order to study it. -

Educating for Cross-Cultural Syncretism Through the Arts. Marian R

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1983 Educating for cross-cultural syncretism through the arts. Marian R. Templeman University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Templeman, Marian R., "Educating for cross-cultural syncretism through the arts." (1983). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 3922. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/3922 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDUCATING FOR CROSS-CULTURAL SYNCRETISM THROUGH THE ARTS A Dissertation Presented By MARIAN R. TEMPLEMAN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION May 1983 School of Education Marian R. Templeman All Rights Reserved ( EDUCATING FOR CROSS-CULTURAL SYNCRETISM THROUGH THE ARTS A Dissertation Presented By MARIAN R. TEMPLEMAN Approved as to style and content by: Dr. George E. Urch, Chairperson of Committee Dr. Richard Konicek, Member Dr. Hariharan Swaminathan, Acting Dean School of Education i ii DediGated to the Creating Spirit and to my father and mother Mr. and Mrs. James G. Tempieman also to persons of the St. Regis-Akwesasne Reservation and aeolianimic persons everywhere IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Dr. George Urch, as chairperson, is most worthy of deepest gratitude for his wisdom, considerate assistance, patient encouragement--for being the epitome of "a perfect gentleman and a scholar." Dr. -

Evidence from the Ethnographic Atlas

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Munich Personal RePEc Archive MPRA Munich Personal RePEc Archive Pacification and Gender in Colonial Africa: Evidence from the Ethnographic Atlas Morgan Henderson and Warren Whatley University of michigan, University of Michigan 7 December 2014 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/61203/ MPRA Paper No. 61203, posted 10 January 2015 08:14 UTC Pacification and Gender in Colonial Africa: Evidence from the Ethnographic Atlas Morgan Henderson [email protected] Warren C. Whatley [email protected] Department of Economics University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 This version: December 7, 2014 JEL Classifications: J12, N47, O15, P48 Keywords: Colonialism, Africa, Property Rights, Gender, Family Structure Abstract We combine the date-of-observation found in Murdock’s Ethnographic Atlas and a newly-constructed dataset on the date-of-colonization at the ethnic-group level to study the effects of the duration of colonial rule on a variety of political, economic, and social characteristics of ethnic groups in Africa. We find that the duration of colonial rule is correlated with a dramatic shift in gender roles in Africa by increasing the relative status of men in lineage and inheritance systems but also reducing polygyny as a marriage system. A causal role for the duration of colonial rule is confirmed by a difference-in-difference analysis that uses never-colonized ethnic groups as a control group and by an analysis of changes in kinship terminology that tests for within-group changes in descent and inheritance rules. -

Society: the Basics, 10/E © 2009 John J

Society: The Basics, 10/e © 2009 John J. Macionis ISBN-13: 9780135018828 ISBN-10: 013501882X Visit www.pearsonhighered.com/replocator to contact your Pearson Publisher’s Representative. sample chapter The pages of this Sample Chapter may have slight variations in final published form. www.pearsonhighered.com Culture refers to a way of life, which includes what people do (such as forms of dance) and what people have (such as clothing). But culture is not only about what we see on the outside; it also includes what's inside— our thoughts and feelings. CHAPTER 2 Culture THIS CHAPTER focuses on the concept of “culture,” which refers to a society’s CHAPTER OVERVIEW entire way of life. Notice that the root of the word “culture” is the same as that of the word “cultivate,” suggesting that people living together actually “grow” their way of life over time. It’s late on a Tuesday night, but Fang Lin gazes intently at her computer screen. Dong, who is married to Fang, walks up behind her chair. “I’m trying to finish organizing our investments,” Fang explains, speaking in Chinese. “I didn’t realize that we could do all this online in our own language,” Jae says, reading the screen. “That’s great. I like that a lot.” Fang and Dong are not alone in feeling this way. Back in 1990, executives of Charles Schwab & Co., a large investment brokerage corporation, gathered in a conference room at the company’s headquarters in San Francisco to discuss ways they could expand their business. They came up with the idea that the company would profit by giving greater attention to the increasing cultural diversity of the United States.