Overcoming Bioethical, Legal, and Hereditary Barriers to Mitochondrial Replacement Therapy in the USA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Undertanding Human Relations (Kinship Systems) Laurent Dousset

Undertanding Human Relations (Kinship Systems) Laurent Dousset To cite this version: Laurent Dousset. Undertanding Human Relations (Kinship Systems). N. Thieberger. The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Fieldwork, Oxford University Press, pp.209-234, 2011. halshs-00653097 HAL Id: halshs-00653097 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00653097 Submitted on 6 Feb 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Published as: Dousset, Laurent 2011. « Undertanding Human Relations (Kinship Systems) », in N. Thieberger (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Fieldwork. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 209-234 The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Fieldwork Edited by Nick Thieberger Oxford University Press Laurent Dousset EHESS (Advanced School for Social Studies) CREDO (Centre de Recherche et de Documentation sur l’Océanie) 3 place Victor Hugo F – 13003 Marseilles [email protected] Part four: Collaborating with other disciplines Chapter 13 : Anthropology / Ethnography. Understanding human relations (kinship systems). Kungkankatja, minalinkatja was the answer of an elderly man to my question, 'How come you call your cousins as if they were your siblings?', when I expected to hear different words, one for sibling and one for cousin. -

Major Trends Affecting Families in Central America and the Caribbean

Major Trends Affecting Families in Central America and the Caribbean Prepared by: Dr. Godfrey St. Bernard The University of the West Indies St. Augustine Trinidad and Tobago Phone Contacts: 1-868-776-4768 (mobile) 1-868-640-5584 (home) 1-868-662-2002 ext. 2148 (office) E-mail Contacts: [email protected] [email protected] Prepared for: United Nations Division of Social Policy and Development Department of Economic and Social Affairs Program on the Family Date: May 23, 2003 Introduction Though an elusive concept, the family is a social institution that binds two or more individuals into a primary group to the extent that the members of the group are related to one another on the basis of blood relationships, affinity or some other symbolic network of association. It is an essential pillar upon which all societies are built and with such a character, has transcended time and space. Often times, it has been mooted that the most constant thing in life is change, a phenomenon that is characteristic of the family irrespective of space and time. The dynamic character of family structures, - including members’ status, their associated roles, functions and interpersonal relationships, - has an important impact on a host of other social institutional spheres, prospective economic fortunes, political decision-making and sustainable futures. Assuming that the ultimate goal of all societies is to enhance quality of life, the family constitutes a worthy unit of inquiry. Whether from a social or economic standpoint, the family is critical in stimulating the well being of a people. The family has been and will continue to be subjected to myriad social, economic, cultural, political and environmental forces that shape it. -

The Effect of Reproductive Compensation on Recessive Disorders Within Consanguineous Human Populations

Heredity (2002) 88, 474–479 2002 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0018-067X/02 $25.00 www.nature.com/hdy The effect of reproductive compensation on recessive disorders within consanguineous human populations ADJ Overall1,2, M Ahmad1 and RA Nichols1 1School of Biological Sciences, Queen Mary, University of London, UK We investigate the effects of consanguinity and population results show how reproductive compensation can effectively substructure on genetic health using the UK Asian popu- counteract the purging of deleterious alleles within con- lation as an example. We review and expand upon previous sanguineous populations. Whereas inbreeding does not treatments dealing with the deleterious effects of con- elevate the equilibrium frequency of affected individuals, sanguinity on recessive disorders and consider how other reproductive compensation does. We suggest this effect factors, such as population substructure, may be of equal must be built into interpretations of the incidence of genetic importance. For illustration, we quantify the relative risks of disease within populations such as the UK Asians. Infor- recessive lethal disorders by presenting some simple calcu- mation of this nature will benefit health care workers who lations that demonstrate the effect ‘reproductive compen- inform such communities. sation’ has on the maintenance of recessive alleles. The Heredity (2002) 88, 474–479. DOI: 10.1038/sj/hdy/6800090 Keywords: marriage; inbreeding; mortality; morbidity; genetic counselling Introduction whether reproductive compensation, at the level ident- ified by Koeslag and Schach (1984), can effectively The majority of the UK Asian population can trace their counteract the purging of deleterious alleles within con- origins to the Punjab region of India and Pakistan within sanguineous populations. -

(1908): Recent Studies in Human Heredity

NOTES AND LITERATURE HEREDITY Recent Studies in Human Heredity.-j\Iustthe fallacy always persist that all ancient and powerful families are necessarily degenerate? As long ago as 1881, Paul Jacoby wrote a book1 to prove that the assumptionof rank and power has always been followedby mentaland physicaldeteriorations ending in sterility and the extinctionof the race. By collectingtogether all evi- dence supportinghis preconceivedtheory, by tracing only the well-knownfamilies in whichpathological conditions were heredi- tary,by failing to treat of dozens of otherswhose recordswould not have supportedhis thesis,by saying everythinghe possibly could that was bad about everyone (followingalways the hostile historians), by ignoring everywherethe normal and virtuous members,he was able to presentwhat was to the uninformedan apparently overwhelmingarray of proof. In regard to the injustice of this one-sided picture I have already had some- thingto say in "M'Nlentaland M\IoralHeredity in Royalty, first publishedsome six years ago. A furtherstudy based upon Jacoby's unsound foundations has recentlycome to my notice,3and althougha well-miadebook containingan interestingseries of 278 portrait illustrations,is necessarilyquite as misleadingas the older structureon which it rests. The main idea of Dr. Galippe is to show that the great swollen protrudingunderlip which descended amionogthe Hiaps- burgs of Austria, Spain and allied houses,and also the protrud- ing underjaw (progil)athismine in e'rieuitr), are stigmata of de- generacy,and to demonstratethis he places beside his portraits, quotationsfrom the writingsof Jacoby. Galippe uses no statistical methods, not even arithmetical counting,and appears to be totally ignorant of English bio- metric writings. His general conclusionsabout the causes of degeneracy (aristocratic environment,etc.) are quite as mis- Etudes sur la selection chez I homem. -

How Understanding the Aboriginal Kinship System Can Inform Better

How understanding the Aboriginal Kinship system can inform better policy and practice: social work research with the Larrakia and Warumungu Peoples of the Northern Territory Submitted by KAREN CHRISTINE KING BSW A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Social Work Faculty of Arts and Science Australian Catholic University December 2011 2 STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP AND SOURCES This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No other person‟s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. All research procedures reported in the thesis received the approval of the Australian Catholic University Human Research Ethics Committee. Karen Christine King BSW 9th March 2012 3 4 ABSTRACT This qualitative inquiry explored the kinship system of both the Larrakia and Warumungu peoples of the Northern Territory with the aim of informing social work theory and practice in Australia. It also aimed to return information to the knowledge holders for the purposes of strengthening Aboriginal ways of knowing, being and doing. This study is presented as a journey, with the oral story-telling traditions of the Larrakia and Warumungu embedded and laced throughout. The kinship system is unpacked in detail, and knowledge holders explain its benefits in their lives along with their support for sharing this knowledge with social workers. -

In Search of Your Immigrant Ancestor! a Resource to Introduce Youth Ages 12 to 14 Years to Genealogy at Home, in School, Or in Youth Groups Created by John H

In Search of Your Immigrant Ancestor! A Resource to Introduce Youth Ages 12 to 14 Years to Genealogy at Home, in School, or in Youth Groups Created by John H. Althouse AGS Genealogy for Youth Project Project Youth for Genealogy AGS Copyright © 2019 Alberta Genealogical Society All rights reserved This publication is the sole property of the Alberta Genealogical Society. It is meant for the use of school classes, youth groups, or individual families who wish to introduce genealogy and / or family history to children and youth. The publication may be downloaded and used exclusively for this purpose. The publication is free. No one shall sell or otherwise collect or receive financial benefit for this resource. Alberta Genealogical Society, #162, 14315 -118 Avenue NW, Edmonton, Alberta T5L 4S6 Canada. Resource Created by John H. Althouse, BA, B Ed, Ed Diploma BOOKS IN THIS SERIES: AGS Genealogy for Youth Project Series My Family Now and in the Past! A Resource to Introduce Children Ages 6 to 8 years to Genealogy at Home, in School, or in Youth Groups Our Family Home - Here in Alberta and Far Away! A Resource to Introduce Children Ages 9 to 11 Years to Genealogy at Home, in School, or in Youth Groups In Search of Your Immigrant Ancestor! A Resource to Introduce Youth Ages 12 to 14 Years to Genealogy at Home, in School, or in Youth Groups (additional books in future) CANADIAN CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATIONS DATA John H. Althouse, 1946 – ISBN 978 - 1 - 55194 - 071 - 7 This publication as a pdf document will be available on the Alberta Genealogy website at http://www.abgenealogy.ca/ The images in this publication are reproduced with the permission of the holders as indicated on “Credits” p.57. -

Inheriting Genetic Conditions

Help Me Understand Genetics Inheriting Genetic Conditions Reprinted from MedlinePlus Genetics U.S. National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health Department of Health & Human Services Table of Contents 1 What does it mean if a disorder seems to run in my family? 1 2 Why is it important to know my family health history? 4 3 What are the different ways a genetic condition can be inherited? 6 4 If a genetic disorder runs in my family, what are the chances that my children will have the condition? 15 5 What are reduced penetrance and variable expressivity? 18 6 What do geneticists mean by anticipation? 19 7 What are genomic imprinting and uniparental disomy? 20 8 Are chromosomal disorders inherited? 22 9 Why are some genetic conditions more common in particular ethnic groups? 23 10 What is heritability? 24 Reprinted from MedlinePlus Genetics (https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/) i Inheriting Genetic Conditions 1 What does it mean if a disorder seems to run in my family? A particular disorder might be described as “running in a family” if more than one person in the family has the condition. Some disorders that affect multiple family members are caused by gene variants (also known as mutations), which can be inherited (passed down from parent to child). Other conditions that appear to run in families are not causedby variants in single genes. Instead, environmental factors such as dietary habits, pollutants, or a combination of genetic and environmental factors are responsible for these disorders. It is not always easy to determine whether a condition in a family is inherited. -

Ancient Genomes Provide Insights Into Family Structure and the Heredity of Social Status in the Early Bronze Age of Southeastern Europe A

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Ancient genomes provide insights into family structure and the heredity of social status in the early Bronze Age of southeastern Europe A. Žegarac1,2, L. Winkelbach2, J. Blöcher2, Y. Diekmann2, M. Krečković Gavrilović1, M. Porčić1, B. Stojković3, L. Milašinović4, M. Schreiber5, D. Wegmann6,7, K. R. Veeramah8, S. Stefanović1,9 & J. Burger2* Twenty-four palaeogenomes from Mokrin, a major Early Bronze Age necropolis in southeastern Europe, were sequenced to analyse kinship between individuals and to better understand prehistoric social organization. 15 investigated individuals were involved in genetic relationships of varying degrees. The Mokrin sample resembles a genetically unstructured population, suggesting that the community’s social hierarchies were not accompanied by strict marriage barriers. We fnd evidence for female exogamy but no indications for strict patrilocality. Individual status diferences at Mokrin, as indicated by grave goods, support the inference that females could inherit status, but could not transmit status to all their sons. We further show that sons had the possibility to acquire status during their lifetimes, but not necessarily to inherit it. Taken together, these fndings suggest that Southeastern Europe in the Early Bronze Age had a signifcantly diferent family and social structure than Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age societies of Central Europe. Kinship studies in the reconstruction of prehistoric social structure. An understanding of the social organization of past societies is crucial to understanding recent human evolution, and several generations of archaeologists and anthropologists have worked to develop a suite of methods, both scientifc and conceptual, for detecting social conditions in the archaeological record 1–4. -

An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies

11 Close–Distant: An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies Abstract This chapter looks at the evidence for the close–distant dichotomy in the kinship systems of Australian Aboriginal societies. The close– distant dichotomy operates on two levels. It is the distinction familiar to Westerners from their own culture between close and distant relatives: those we have frequent contact with as opposed to those we know about but rarely, or never, see. In Aboriginal societies, there is a further distinction: those with whom we share our quotidian existence, and those who live at some physical distance, with whom we feel a social and cultural commonality, but also a decided sense of difference. This chapter gathers a substantial body of evidence to indicate that distance, both physical and genealogical, is a conception intrinsic to the Indigenous understanding of the function and purpose of kinship systems. Having done so, it explores the implications of the close–distant dichotomy for the understanding of pre-European Aboriginal societies in general—in other words: if the dichotomy is a key factor in how Indigenes structure their society, what does it say about the limits and integrity of the societies that employ that kinship system? 363 SKIN, KIN AND CLAN Introduction Kinship is synonymous with anthropology. Morgan’s (1871) Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family is one of the founding documents of the discipline. It also has an immediate connection to Australia: one of the first fieldworkers to assist Morgan in gathering his data was Lorimer Fison, who, later joined by A. -

Third Degree of Consanguinity

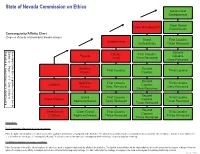

State of Nevada Commission on Ethics Great-Great Grandparents 4 Great Grand Great Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Consanguinity/Affinity Chart 3 5 (Degrees of family relationship by blood/marriage) Grand First Cousins Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Twice Removed 2 4 6 Second Uncles First Cousins Parents Cousins Aunts Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 Brothers Second First Cousins Third Cousins Sisters Cousins 2 4 6 8 Second Nephews First Cousins Third Cousins Children Cousins Nieces Once Removed Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 9 Second Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Grand Children Cousins Nephews/Nieces Twice Removed Twice Removed 1 2 4 6 Twice Removed 8 0 Second Great Grand Great Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Cousins Children Nephews/Nieces Thrice Removed Thrice Removed 1 3 5 7 Thrice Removed 9 1 Instructions: For Consanguinity (relationship by blood) calculations: Place the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by consanguinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the public officer/employee. Anyone in a box numbered 1, 2, or 3 is within the third degree of consanguinity. Nevada Ethics in Government Law addresses consanguinity within third degree by blood, adoption or marriage. For Affinity (relationship by marriage) calculations: Place the spouse of the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by affinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the spouse and the degree of distance from the public officer/employee by affinity. A husband and wife are related in the first degree by marriage. -

Influences on Your Health

InfluencesInfluences onon YourYour HealthHealth ChapterChapter 11 LessonLesson 22 HeredityHeredity • Heredity: all the traits and properties that are passed along biologically from both parents to child. • To some degree this determines your general level of health. • You inherit physical traits such as the color of your hair and eyes, shape of your nose and ears, as well as your body type and size. • You also inherit basic intellectual abilities as well as tendencies toward specific diseases. EnvironmentEnvironment • Environment: The sum of your total surroundings- your family, where you grew up, where you live now, and all of your experiences. • Your environment also includes the people in your life as well as your culture. PhysicalPhysical EnvironmentEnvironment • Your physical environment can affect all areas of your health. • Positive environmental influences include: parks, jogging paths, recreational facilities, health care facilities, low crime. • Negative environmental influences include: pollutants such as smog and smoke, high crime, poor access to medical care, exposure to diseases. SocialSocial EnvironmentEnvironment • Your social environment includes your family and other people you come into contact daily. A person who is surrounded by individuals who show love, support, strength, and encouragement is said to have a positive social environment. A healthful positive social environment can help a person rise above adverse physical conditions and create a positive self-image. • A person from an unhealthful social environment may suffer from poor mental and emotional health as a result of rejection, neglect, verbal abuse, and other negative behaviors. SocialSocial EnvironmentEnvironment cont.cont. • An important part of your social environment, especially during the teen years is your peers. -

The Joking Relationship and Kinship: Charting a Theoretical Dependency

JASO 24/3 (1993): 251-263 THE JOKING RELATIONSHIP AND KINSHIP: CHARTING A THEORETICAL DEPENDENCY ROBERT PARKIN ALTHOUGH the anthropology of jokes and of humour generally is a relatively new phenomenon (see, for example, Apte 1985)" the anthropology of joking has a long history. It has been taken up at some point or another by most of the main theoreticians of the subject and their treatment of it often serves to characterize their general approach; moreover, there can be few anthropologists who have not enoountered it and had to deal with it in the field. What has stimulated anthropologists is the fact that societies are almost invariably internally differentiated in some way and that one does not joke with everyone. The very fact that joking has to involve at least two people ensures its social character, while the requirement not to joke is equally obviously a social injunction. The questions anthropologists have asked themselves are, why the difference, and how is it manifested in any particular society? This is a revised version of a paper first given on 26 June 1989 at the Institut fUr Ethnologie, Freie UniversiUit Berlin, in a seminar series chaired by Dr Burkhard Schnepel and entitled 'The Fool in Social Anthropological Perspective'. A German version was presented subsequently at the Deutsche Gesellschaft filr VOlkerkunde conference in Munich on 18 October 1991 and is to be published in due course in a book edited by Dr Schnepel and Dr Michael Kuper. In the present version certain aspects of the material argument have been modified, though the style of the original oral delivery has been left largely untouched.