Moving in Late Medieval Harness: Exploration of a Lost Embodied Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interpretation of Fiore Dei Liberi's Spear Plays

Acta Periodica Duellatorum, Hands On section, articles 131 Interpretation of Fiore dei Liberi’s Spear Plays Jakub Dobi Ars Ensis [email protected] Abstract – How did Fiore Furlano use a spear? What is the context, purpose, and effect of entering a duel armed with a spear? My article- originally a successful thesis work for an Ars Ensis Free Scholler title- describes in detail what I found out by studying primary sources (Fiore’s works), related sources (contemporary and similar works), and hands-on experience in controlled play practice, as well as against uncooperative opponents. In this work I cover the basics- how to hold the spear, how to assume Fiore’s stances, how to attack, and how to defend yourself. I also argue that the spear is not, in fact, a preferable weapon to fence with in Fiore’s system, at least not if one uses it in itself. It is however, a reach advantage that has to be matched, and thus the terribly (mutually) unsafe situation of spear versus spear occurs. As a conclusion, considering context and illustrations of spear fencing, I argue that the spear is only to be considered paired with other weapons, like dagger, or sword. In fact, following Fiore’s logic, we can assume he used the spear to close the distance to use a weapon he feels more in control with. Keywords – Fiore, Furlano, Liberi, Italian, duel, spear, Ars Ensis I. PROCESS OF RESEARCH The article itself is largely devoted to trying to point out the less obvious points to make about this specific style of spear fencing. -

Fiore Dei Liberi: 14Th Century Master of Defence

ARMA Historical Study Guide: Fiore Dei Liberi: 14th century Master of Defence By John Clements Unarguably the most important Medieval Italian fighting treatise, the work of Fiore Dei Liberi forms a cornerstone of historical fencing studies. Like many other martial arts treatises from the Medieval and Renaissance eras, we must look analytically at the totality of the author’s teachings. In doing so we come to understand how, rather than consolidating information compartmentally, its manner of technical writing disperses it throughout. In circa 1409, a northern Italian knight and nobleman, Fiore dei Liberi, produced a systematic martial arts treatise that has come to be considered one of the most important works of its kind on close-combat skills. Methodically illustrated and pragmatically presented, his teachings reveal a sophisticated and deadly fighting craft. It is one of the most unique and important texts in the history of fencing and of our Western martial heritage. Master Fiore’s manuscript is today the primary source of study for reconstruction of Italian longsword fencing, combat grappling, and dagger fighting. It currently constitutes the earliest known Italian fencing manual and one of only two so far discovered from the era. Along with dagger and tapered longsword (spadone or spada longa), his work includes armored and unarmored grappling, poleax, mounted combat, and specialized weapons as well as unarmored spear, stick, and staff. His spear (or lance) fighting on foot is a matter of holding sword postures while thrusting or deflecting. His longsword fencing techniques include half- swording, pommel strikes, blade grabbing, disarms, trapping holds, throws, groin kicks, knee stomps, defense against multiple opponents, timed blows to push or leverage the adversary off balance, and even sword throwing. -

Critical Review !1/!76

Guy Windsor Critical Review !1/!76 Recreating Medieval and Renaissance European combat systems: A Critical Review of Veni Vadi Vici, Mastering the Art of Arms vol 1: The Medieval Dagger, and The Duel- list’s Companion, Submitted for examination for the degree of PhD by Publication. Guy Windsor Ipswich, July 2017 !1 Guy Windsor Critical Review !2/!76 Table of Contents Introduction 3 The Primary Sources for the Submitted Works 20 Methodology 37 Results: The Submitted Works 42 Conclusion 60 Works Cited 69 !2 Guy Windsor Critical Review !3/!76 Introduction The aims of this research on historical methods of combat are threefold: historical knowl- edge for its own sake, the reconstruction of these lost combat arts, and the development of pedagogical methods by which these arts can be taught. The objectives are to develop and present working interpretations of three particular sources, Fiore dei Liberi’s Il Fior di Battaglia (1410) Philippo Vadi’s De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi (ca 1480) and Ridolfo Capo- ferro’s Gran Simulacro (1610). By “working interpretations” I mean a clear and reasonably complete training method for acquiring the necessary skills to execute these styles of swordsmanship in practice: so a technical, tactical, and pedagogical method for each style. The methodology includes transcription and translation (where necessary), close reading, tropological analysis, practical experiment, technical practice, and presentation of findings. The results include but are not limited to the three publications submitted for examination, which are: Veni Vadi Vici, published in 2012, which is a transcription, translation and commentary on De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi: this has been extensively corrected and updated, and re- submitted for a second examination after which it will be published. -

Downloaded and Shared for Private Use Only – Republication, in Part Or in Whole, in Print Or Online, Is Expressly Forbidden Without the Written Consent of the Author

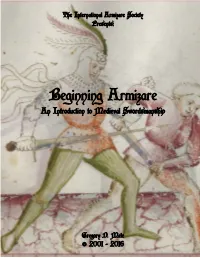

The International Armizare Society Presents: Beginning Armizare An Introduction to Medieval Swordsmanship Gregory D. Mele © 2001 - 2016 Beginning Armizare: An Introduction to Medieval Swordsmanship Copyright Notice: © 2014 Gregory D. Mele, All Rights Reserved. This document may be downloaded and shared for private use only – republication, in part or in whole, in print or online, is expressly forbidden without the written consent of the author. ©2001-2016 Gregory D. Mele Page 2 Beginning Armizare: An Introduction to Medieval Swordsmanship TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 4 Introduction: The Medieval Art of Arms 5 I. Spada a Dui Mani: The Longsword 7 II. Stance and Footwork 9 III. Poste: The Guards of the Longsword 14 IV. Learning to Cut with the Longsword 17 V. Defending with the Fendente 23 VI. Complex Blade Actions 25 VII. Parrata e Risposta 25 Appendix A: Glossary 28 Appendix B: Bibliography 30 Appendix C: Armizare Introductory Class Lesson Plan 31 ©2001-2016 Gregory D. Mele Page 3 Beginning Armizare: An Introduction to Medieval Swordsmanship FOREWORD The following document was originally developed as a study guide and training companion for students in the popular "Taste of the Knightly Arts" course taught by the Chicago Swordplay Guild. It has been slightly revised, complete with the 12 class outline used in that course in order to assist new teachers, small study groups or independent students looking for a way to begin their study of armizare. Readers should note that by no means is this a complete curriculum. There is none of the detailed discussion of body mechanics, weight distribution or cutting mechanics that occurs during classroom instruction, nor an explanation of the number of paired exercises that are used to develop student's basic skills, outside of the paired techniques, or "set-plays," themselves. -

Federazione Italiana Scherma Federation

FEDERAZIONE ITALIANA SCHERMA Stampa: 27/04/2013 18:12 FEDERATION INTERNATIONALE D'ESCRIME Fioretto maschile a squadre Gran Premio Assoluti ANCONA - Camp. Italiani serie C FM-SCM Denominazione Sigla Località Classific 1 A.S.D. POL. PODJGYM AVELLINO AVGYM AVELLINO 2 -12,00 2 A.S.PICCOLO TEATRO MILANO A.S.D. MIPIT MILANO 3 -6,00 3 P.G.S. - I.M.A. A.S.D. BOLOGNA BOIMA BOLOGNA 4 -2,00 4 CLUB SCHERMA FIRENZE A.S.D. FICSF FIRENZE 5 -3,00 5 ACCADEMIA SCHERMA PESCARA ASD PEACC PESCARA 6 -8,00 6 G.S. ARIBERTO CELI MESSINA A.S.D. MECEL MESSINA 7 -9,00 7 CLUB SCHERMA VIAREGGIO A.S.D. LUCSV VIAREGGIO 8 -13,00 8 FIORE DEI LIBERI CIVIDALE UD UDFDL CIVIDALE DEL FRIULI 9 -4,00 9 PENTAMODENA A.S.D. MOPEN MODENA 10 -7,00 10 COMENSE SCHERMA S.S.D. A R.L. COCOM COMO 11 -1,00 11 G.S. "P. GIANNONE" CEGIA CASERTA 12 -11,00 12 ACCADEMIA SCHERMA SPOLETO A.S.D. PGSPO SPOLETO 14 -5,00 13 FOGGIA FENCING ATENEO DI SCHERMA FGFEN FOGGIA 16 -10,00 Pagina 1 di 1 Mod.P.10 SW a cura della TE.S.I.S. di Saverio Tedeschi - Var.SS 115 n.23 - Modica (RG) - Italy - [email protected] - 333-3497135 FEDERAZIONE ITALIANA SCHERMA Gran Premio Assoluti FEDERATION INTERNATIONALE D'ESCRIME Fioretto maschile a squadre ANCONA - Camp. ItalianiStampa: serie C27/04/2013 FM-SCM 18:12 Cod.Soc. Società Sigla Sq.1 Sq.2 Sq.3 Punt. Diff. Stocc. -

Armizare, 1409 an Examination of Fiore Dei Liberi

Raziskava o Fioreju dei liberi in njegovih razpravah, ki opisujejo L`arte dell`armizare, 1409 An examination of Fiore dei liberi and his treatises describing L`arte dell`armizare, c. 1409 • D AVI D M . C V E T B.Sc., Founder and Head Instructor Academy of European Medieval Martial Arts, 927 Dupont St., 2nd floor, Toronto, ON M6H 1Z1, Canada; e-mail: [email protected] Izvleček Excerpt Zapuščini Fioreja dei Liberi, nastali pred Fiore dei Liberi’s legacy created 600 years ago is 600 leti, je v 21. stoletju izkazana čast s skrb- honoured in the 21st century with the careful recon- no rekonstrukcijo in ponovno oživitvijo boril- struction and resurrection of the fighting art he de- ne veščine, ki jo je opisal v svojih razpravah z scribed in his treatises entitled “Flos Duellatorum” naslovom Flos Duellatorum in Fior di Battaglia. and “Fior Battaglia”. This paper will explore the Ta spis raziskuje moža po imenu Fiore in pred- man who bore the name Fiore and conduct a brief stavlja kratko primerjalno analizo treh različic comparative analysis of the three versions of the razprave. Te razprave veljajo za pomembne te- treatise. The treatises are considered important cor- melje današnjih raziskav in rekonstrukcij zgo- nerstones in today’s research and reconstruction of dovinskih borilnih veščin zahoda zaradi svoje historical Western fighting arts given their collection zbirke ilustracij, ki neverjetno jasno pričajo o of illustrations possessing remarkable clarity in con- izročilu te veščine, vsako ilustracijo pa spre- veying the concepts in the art, and the informative mljajo informativna besedila. text accompanying each illustration. -

Fiore Dei Liberi Studies Documentation Master Llwyd Aldrydd, OP

Fiore dei Liberi Studies Documentation Master Llwyd Aldrydd, OP Introduction Fiore dei Liberi’s combat manual is the oldest surviving description of a complete European combat system. Earlier manuals such as Royal Armouries MS I.33 (circa 1320) and the Dobringer manuscript description of the Liechtenaur school focused solely on sword techniques. Fiore describes a complete, consistent, combat system building from wrestling, then adding a dagger, then adding longer range skills with a sword, longsword, pike, and spear. He describes applying the techniques to opponents in armor and while mounted on a horse. Each new scenario builds upon the earlier one and adds a few new, but consistent, movements that the new weapon or situation allows. Most of what is known about Fiore as a person is extrapolated. He was Italian and born around 1350. He traveled extensively, studying swordplay from German and Italian masters. His technique clearly builds on, adapts, and updates or rejects, techniques described in Liechtenaur. But while the Germans are focused on grabbing and holding the initiative in a fight, Fiore advocated a counter-tempo approach where the opponent would initiate a combat pass and the skilled master would interrupt the attack – generally by stepping into the opponent before the attack can develop – and steal the initiative while the opponent is locked into his original attack. Primary Source Material Fiore authored one book describing his combat system which he started in 1409. Four copies of that manuscript are known to have survived to the present day. Each was hand copied, so there are subtle differences between the four and it is debated which differences were intentional – representing a change of mind on a technique – and which are scribal transcription errors. -

On the Art of Fighting: a Humanist Translation of Fiore Dei Liberi's

Acta Periodica Duellatorum, Scholarly section, articles 99 On the Art of Fighting: A Humanist Translation of Fiore dei Liberi’s Flower of Battle Owned by Leonello D’Este Ken Mondschein Anna Maria College / Goodwin College / Massachussets historical swordmanship Abstract – The author presents a study of Bibliothèque National de France MS Latin 11269, a manuscript that he argues was associated with the court of Leonello d’Este and which represents an attempt to “fix” or “canonize” a vernacular work on a practical subject in erudite Latin poetry. The author reviews the life of Fiore dei Liberi and Leonello d’Este and discusses the author’s intentions in writing, how the manuscript shows clear signs of Estense associations, and examines the manuscript both in light of its codicological context and in light of humanist activity at the Estense court. He also presents the evidence for the book having been in the Estense library. Finally, he examines the place of the manuscript in the context of the later Italian tradition of fencing books. A complete concordance is presented in the appendix. Keywords – Leonello d’Este, humanism, Fiore dei Liberi, Latin literature, Renaissance humanism, translation I. INTRODUCTION The Flower of Battle (Flos Duellatorum in Latin or Fior di Battaglia in Italian) of Fiore dei Liberi (c. 1350—before 1425) comes down to us in four manuscripts: Getty MS Ludwig XV 13; Morgan Library M.383; a copy privately held by the Pisani-Dossi family; and Bibliothèque National de France MS Latin 11269.1 Another Fiore manuscript attested in 1 The Pisani-Dossi was published by Novati as Flos duellatorum: Il Fior di battaglia di maestro Fiore dei Liberi da Premariacco, and republished by Nostini in 1982 and Rapisardi as Flos Duellatorum in armis, sine armis, equester et pedester. -

Schola Gladiatoria - Fiore Dei Liberi - Fior Di Battaglia - Flos Duellatorum File:///H:/Data/Schola%20Gladiatoria%20-%20Fiore%20Dei%20Liberi%

Schola Gladiatoria - Fiore dei Liberi - Fior di Battaglia - Flos Duellatorum file:///H:/data/Schola%20Gladiatoria%20-%20Fiore%20dei%20Liberi%... FIORE DEI LIBERI GETTY TRANSLATION MORGAN TRANSLATION FIORE FORUM Most of what we know about Fiore dei Liberi comes from the prologues of the different versions of his treatise, Fior di Battaglia ('Flower of Battle', also known as Flos Duellatorum), and the works of the early 20thC historians Francesco Novati and Luigi Zanutto (who drew on earlier works by Fontanini and others). Fiore, the treatises There are four known surviving versions of his treatise: 1) 'Pisani-Dossi' (PD) - dated to 1409 (1410 by the modern calendar), known at the moment from the facsimile in Francesco Novati's work of 1902. It has been widely reproduced on the internet (as Novati's facsimile is out of copyright) and most of the text accompanying the lessons is in the form of short rhyming couplets. It's prologue has two parts, a Latin one and an Italian one, the former part of this being quite different to the prologues of the othe two versions of Fiore's work. It is dedicated to Niccolo III d'Este, Marquis of Ferrara. The armour shown in the treatise may point to a slightly later date than the other two versions (also, in PD it says Fiore studied for years plus, while in Getty and Morgan it says he has studied for 40 years plus). It has some parts not included in the other two versions. Until recently the original was assumed to have been lost, but it is now known where the manuscript is kept (in a private collection). -

Captain of Fortune: Galeazzo Da Montova

Captain of Fortune: Galeazzo da Montova I will now recall and name some of my students who had to fight in the lists. First among them was the noble and hardy knight Piero dal Verde, who had to fight Piero della Corona. Both of them were German, and the contest had to take place in Perugia. ... Another was the famous, gallant and hardy knight Galeazzo di Capitani da Grimello, better known as Galeazzo da Mantova; he had to cross weapons with the famous French knight Boucicault in Padua. .... None of my students, in particular the ones I have mentioned, have ever possessed a book on the art of combat, with the exception of Galeazzo da Mantova. Galeazzo used to say that without books, nobody can truly be a Master or student in this art. I, Fiore, agree with this. - Fiore dei Liberi, Il Fior di Battaglia The city-state culture of late medieval Italy produced a unique military structure. Initially, each city produced a local militia under the command of its aristocracy, in which the lower classes from the city and its subject territories served as infantry, while the upper classes served as knightly cavalry. But by the early 1300s this system was collapsing. Increased inter-state violence, a growing preference amongst wealthy townsmen to hire others to fulfill their military duties, and the princes’ often justified distrust of arming their own subjects led to an almost complete reliance on paid mercenaries, the condottieri. Named for the condotta, a contract specifying the terms of military service, the condottiero was the consummate professional; well armed, highly trained, and able to remain in the field indefinitely.. -

The Knightly Art of Combat of Filippo Vadi (Italian Master at Arms of the Xv Century)

THE KNIGHTLY ART OF COMBAT OF FILIPPO VADI (ITALIAN MASTER AT ARMS OF THE XV CENTURY) (WORKING TITLE) BY MARCO RUBBOLI, LUCA CESARI DEDICATION This book is dedicated, for their patience in bearing our frantic dedication to bring back to life the ancient Italian martial science, to our wives and daugherts Irene and Sofia Rubboli and Barbara and Sara Cesari. The authors would like to thank: - our Italian publishing house: Il Cerchio, and in particular Luigi Battarra (Marozzo’s man in Rimini) and Adolfo Morganti for all their precious backing and collaboration, also in relation to this new edition in English; - our U.S. publishing house: Paladin Press, a stronghold of the re-born European martial arts; - John Clements of the ARMA, who was the first to suggest us to publish a US edition of Vadi’s treatise, and introduced us to Paladin Press. - our Society “Sala d’Arme Achille Marozzo”, for its continued, disinterested and loyal collaboration that permitted us to clarify many obscure points in the teachings not only of Filippo Vadi, but also of the other Italian authors of the Middle Ages and of the Bolognese School, and in particular the ones that had the patience to test and discuss the techniques contained herein: Domenico Giannuzzi, Luciano Carini, Andrea Cestaro, Riccardo Ciocca, Davide Longhi, Alessandro Battistini, Augusto Borgognoni, Giacomo Miano, Omero Pizzinelli, Filippo Giovannini, Davide Venturi, Maria Giovanna Bassi, Stefano Di Duca, Federico Ercolani, Luca Girolimetto, Federico Panciroli, Corrado Pirri, William Vannini, Cristina Cacciaguerra, Francesca Crociati, Lorenzo Di Masi, Marco Piraccini, Marinella Rocchi, Omar Roffilli. Su concessione del Ministero per i beni culturali e ambientali –Italia On concession of the Ministry for cultural and environmental goods – Italy SHORT NOTE TO THE TRANSLATION “Traduttore = traditore”, i.e. -

The Martial Arts of Medieval Europe

THE MARTIAL ARTS OF MEDIEVAL EUROPE Brian R. Price Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2011 APPROVED: Laura Stern, Major Professor Geoffrey Wawro, Committee Member Adrian R. Lewis, Committee Member Robert M. Citino, Committee Member Stephen Forde, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Price, Brian R. The Martial Arts of Medieval Europe. Doctor of Philosophy (History), August 2011, 310 pp., 2 tables, 6 illustrations, bibliography, 408 titles. During the late Middle Ages and into the Renaissance, fighting books—Fechtbücher— were produced in northern Italy, among the German states, in Burgundy, and on the Iberian peninsula. Long dismissed by fencing historians as “rough and untutored,” and largely unknown to military historians, these enigmatic treatises offer important insights into the cultural realities for all three orders in medieval society: those who fought, those who prayed, and those who labored. The intent of this dissertation is to demonstrate, contrary to the view of fencing historians, that the medieval works were systematic and logical approaches to personal defense rooted in optimizing available technology and regulating the appropriate use of the skills and technology through the lens of chivalric conduct. I argue further that these approaches were principle-based, that they built on Aristotelian conceptions of arte, and that by both contemporary and modern usage, they were martial arts. Finally, I argue that the existence of these martial arts lends important insights into the world-view across the spectrum of Medieval and early Renaissance society, but particularly with the tactical understanding held by professional combatants, the knights and men-at-arms.