Guidance for Protected Bike Lanes Christopher Monsere, Ph.D., Nathan Mcneil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dissecting the Safety Benefits of Protected Intersection Design Features

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Transportation Engineering Masters Projects Civil and Environmental Engineering 2019 DISSECTING THE SAFETY BENEFITS OF PROTECTED INTERSECTION DESIGN FEATURES Nicholas Campelll University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cee_transportation Part of the Transportation Engineering Commons Campelll, Nicholas, "DISSECTING THE SAFETY BENEFITS OF PROTECTED INTERSECTION DESIGN FEATURES" (2019). Transportation Engineering Masters Projects. 13. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cee_transportation/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Civil and Environmental Engineering at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transportation Engineering Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DISSECTING THE SAFETY BENEFITS OF PROTECTED INTERSECTION DESIGN FEATURES A Master’s Project Presented by NICHOLAS CAMPBELL Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN CIVIL ENGINEERING MASTER OF REGIONAL PLANNING May 2019 Dual Degree in Civil Engineering and Regional Planning ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many thanks are extended to my committee for their guidance and assistance throughout this process, special thanks to Dr. Michael Knodler Jr. and Dr. Mark Hamin for creating the dual degree path in Transportation Engineering and Regional Planning. A big thanks to those who helped me learn how the driving simulator works, especially Ganesh Pai Mangalore and Katerina Deliali. iii ABSTRACT DISSECTING THE PERFORMANCE SAFETY BENEFITS OF PROTECTED INTERSECTION DESIGN MAY 2019 NICHOLAS CAMPBELL, M.S.C.E, UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST MRP, UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST Directed by: Mark Hamin & Michael A. -

Guidance for Protected/Buffered Bike Lanes with Delineators: Literature Search July 6, 2017

Guidance for Protected/Buffered Bike Lanes with Delineators: Literature Search July 6, 2017 Prepared for: Marcus Bekele Prepared by: Karen Neinstadt Resources searched: Transport database, Web, MnDOT Library catalog, TRB Research in Progress Summary: This literature search reflects results on protected and/or buffered bike lanes. Sometimes the phrase, “cycle track” is also used. The term “delineator” was not consistent in the results but it is included where found and relevant. Most Relevant Results Michigan Street Protected Bike Lane Demonstration Project (Duluth-Superior Metropolitan Interstate Council) http://dsmic.org/study/pbl/ FHWA Separated Bike Lane Planning and Design Guide https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/bicycle_pedestrian/publications/separated_bikelane_pdg/page00.cfm Lessons from the Green Lanes: Evaluating Protected Bike Lanes in the U.S. https://bikeportland.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/NITC-RR-583_ProtectedLanes_FinalReportb.pdf Minneapolis is Breaking Bicycling Ground with New Protected Lanes: Here’s What’s Working https://www.minnpost.com/cityscape/2015/09/minneapolis-breaking-bicycling-ground-new-protected-lanes- here-s-what-s-working Understanding Bicycle Markings in Minneapolis: A Guide for Motorists and Bicyclists http://www.minneapolismn.gov/www/groups/public/@publicworks/documents/images/wcms1p-083551.pdf Minneapolis Plans Big Push for Protected Bike Lanes in City Core http://www.startribune.com/minneapolis-plans-big-push-for-protected-bike-lanes-in-city-core/294450161/ Bikeways for Everyone: Protected Bike Lanes http://www.bikewaysforeveryone.org/protected_bike_lanes Title: Using Simulation to Assess and Reduce Conflicts between Drivers and Bicyclists. URL: http://rip.trb.org/view/1459790 Abstract: Separated bicycle lanes, or cycle tracks, are increasing in popularity across the nation. -

FHWA Bikeway Selection Guide

BIKEWAY SELECTION GUIDE FEBRUARY 2019 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave Blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED February 2019 Final Report 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. FUNDING NUMBERS Bikeway Selection Guide NA 6. AUTHORS 5b. CONTRACT NUMBER Schultheiss, Bill; Goodman, Dan; Blackburn, Lauren; DTFH61-16-D-00005 Wood, Adam; Reed, Dan; Elbech, Mary 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION VHB, 940 Main Campus Drive, Suite 500 REPORT NUMBER Raleigh, NC 27606 NA Toole Design Group, 8484 Georgia Avenue, Suite 800 Silver Spring, MD 20910 Mobycon - North America, Durham, NC 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) 10. SPONSORING/MONITORING AND ADDRESS(ES) AGENCY REPORT NUMBER Tamara Redmon FHWA-SA-18-077 Project Manager, Office of Safety Federal Highway Administration 1200 New Jersey Avenue SE Washington DC 20590 11. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 12a. DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY STATEMENT 12b. DISTRIBUTION CODE This document is available to the public on the FHWA website at: NA https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/ped_bike 13. ABSTRACT This document is a resource to help transportation practitioners consider and make informed decisions about trade- offs relating to the selection of bikeway types. This report highlights linkages between the bikeway selection process and the transportation planning process. This guide presents these factors and considerations in a practical process- oriented way. It draws on research where available and emphasizes engineering judgment, design flexibility, documentation, and experimentation. 14. SUBJECT TERMS 15. NUMBER OF PAGES Bike, bicycle, bikeway, multimodal, networks, 52 active transportation, low stress networks 16. PRICE CODE NA 17. SECURITY 18. SECURITY 19. SECURITY 20. -

A Historical Perspective on the AASHTO Guide for The

1 A Historical Perspective on the AASHTO Guide for the Development of Bicycle Facilities 2 and the Impact of the Vehicular Cycling Movement 3 4 5 William Schultheiss, PE* 6 [email protected] 7 Toole Design Group, LLC 8 8484 Georgia Avenue, Suite 800 9 Silver Spring, MD 20910 10 Tel: 301-927-1900 11 Fax: 301-927-2800 12 13 Rebecca L. Sanders, PhD 14 [email protected] 15 Toole Design Group, LLC 16 319 SW Washington Street, Suite 800 17 Portland, OR 97204 18 Tel: 503-205-4607 19 20 Jennifer Toole, AICP, ASLA 21 [email protected] 22 Toole Design Group, LLC 23 8484 Georgia Avenue, Suite 800 24 Silver Spring, MD 20910 25 Tel: 301-927-1900 26 Fax: 301-927-2800 27 28 29 *Corresponding author 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 Word count: 6890 words + 2 figures and 1 table = 7640 words Schultheiss, Sanders, Toole 2 1 1. ABSTRACT 2 This paper draws from a literature review and interviews to demonstrate the impact of advocacy, 3 research, and culture on guidance for design users, bike lanes and separated (protected) bike 4 lanes in the American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO) Bicycle 5 Guide content from 1974 to present. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, a bicycle renaissance in 6 America resulted in efforts at the local, state, and federal level to encourage bicycling. After 7 Davis, California, became the first community in the United States to build a network of bike 8 lanes, a new brand of bicycle advocacy – vehicular cycling (VC) – formed to oppose efforts to 9 separate bicyclists from motorized traffic based on fears of losing the right to use public roads. -

Contextual Guidance at Intersections for Protected Bicycle Lanes

Portland State University PDXScholar Transportation Research and Education Center TREC Final Reports (TREC) 12-1-2019 Contextual Guidance at Intersections for Protected Bicycle Lanes Christopher M. Monsere Portland State University, [email protected] Nathan McNeil Portland State University Yi Wang Portland State University Rebecca Sanders Toole Design Group Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/trec_reports Part of the Transportation Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Monsere, C., N. McNeil, Y. Wang, R. Sanders, R. Burchfield and .W Schultheiss. Contextual Guidance at Intersections for Protected Bicycle Lanes. Final Report. NITC-RR- 987. Portland, OR: Transportation Research and Education Center (TREC), November 2019. https://dx.doi.org/10.15760/trec.241 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in TREC Final Reports by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Final Report 987 December 2019 Contextual Guidance at Intersections for Protected Bicycle Lanes Chris Monsere, Ph.D. Nathan McNeil, M.U.R.P. Yi Wang, Ph.D. Rebecca Sanders, Ph.D. Robert Burchfield, P.E. William Schultheiss, P.E. NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNITIES nitc-utc.net CONTEXTUAL GUIDANCE AT INTERSECTIONS FOR PROTECTED BICYCLE LANES Final Report NITC-RR-987 by Christopher Monsere Nathan McNeil Yi Wang Portland State University Rebecca Sanders Robert Burchfield William Schultheiss Toole Design Group for National Institute for Transportation and Communities (NITC) P.O. Box 751 Portland, OR 97207 December 2019 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. -

Designing for On-Road Bikeways

Designing for Bicyclist Safety Module B DESIGNING ON-ROAD BIKEWAYS LEARNING OUTCOMES Describe features of on-road bikeways Select design criteria for on-road bikeways in various contexts BICYCLE CHARACTERISTICS BICYCLE CHARACTERISTICS Height Handlebar - 36-44 in Eye - 60 in Operating - 100 in Width Physical – 30 in Minimum operating – 48 in Preferred operating – 60 in OLDER BIKEWAY TYPES “Bike Route” “Bike Path” Neither term is clear They are all bikeways BIKEWAY NETWORK Just like roads and sidewalks, bikeways need to be part of an connected network Combine various types, including on and off-street facilities HIERARCHY OF BIKEWAYS Shared-Use Paths Separated Bike Lanes Bike Lanes Shoulders Shared Roadway Photo by Harvey Muller Photo by SCI Photo by Harvey Muller Photo by SCI Designing On-Road Bikeways SHARED ROADWAY Photo by Harvey Muller SHARED ROADWAY Most common— roads as they are Appropriate on low-volume or low-speed 85% or more of a well-connected grid SHARED LANES Unless prohibited, all roads have shared lanes No special features for: Minor roads Low volumes (< 1000 vpd) Speeds vary (urban v. rural) SHARED LANES Supplemental features Pavement markings or “sharrows” Detectors & signal timing SHARED LANE MARKING Lateral position Connect gaps in bike lanes Roadway too narrow for passing Position in intersections & transitions SHARED ROAD SIGNS Ride side-by-side? Chase bicyclist? Warning or regulation? Opposite forces? Philadelphia, PA ...and who “shares”? New Orleans, LA California SHARED ROAD SIGNS -

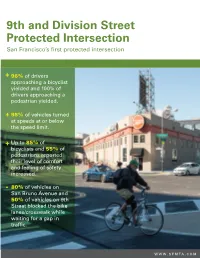

9Th and Division Street Protected Intersection San Francisco’S First Protected Intersection

9th and Division Street Protected Intersection San Francisco’s first protected intersection + 96% of drivers approaching a bicyclist yielded and 100% of drivers approaching a pedestrian yielded. + 98% of vehicles turned at speeds at or below the speed limit. + Up to 85% of bicyclists and 55% of pedestrians reported their level of comfort and feeling of safety increased. - 80% of vehicles on San Bruno Avenue and 50% of vehicles on 9th Street blocked the bike lanes/crosswalk while waiting for a gap in traffic. WWW.SFMTA.COM Division Street is a key east-west corridor Project Location for people biking to Caltrain, the Mission 9th Street and Division Street District, AT&T Ballpark, and the South Beach Date of Implementation area. However, in the past five years there December 2016 were 106 collisions along the Division Street Project Elements Protected Intersectioncorridor, Design including two traffic at deaths. Division – Buffered Street and parking-protected & bike 9thlanes Street – Raised crosswalks To increase safety and comfort in the area, – New sidewalk along the west side of 9th the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Street – Painted safety zones and low concrete Agency (SFMTA) implemented a protected elements intersection at the 9th Street/Division Street/ San Bruno Avenue intersection. This location Key Evaluation Metrics – Vehicle Approach Speed is San Francisco’s first implementation of the – Conflict Behavior at Key Locations protected intersection design concept. – Yielding Rates – Perception of Safety 9 th S eet tr Str e e an t n an Br Buered Bike Lanes Two-Way Street Pedestrian Safety Island New Sidewalk Perpendicular Parking Raised Crossing Division Street Parking Protected Bikeway Division Street Painted Safety Zones V e r Raised Crossing m o n t S t r e e Sa t n P B o Corner Safety Island r t u r e n r o o A A v v enu e n u 9th Street/Division Street Protected Intersection e e SFMTA.COM Division/13th Street Safety Project For more information, please contact Will Tabajonda at [email protected]. -

The Relationship Between Separated Bicycle Lanes and Bicycle Crashes in Denver, Colorado

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Community and Regional Planning Program: Student Projects and Theses Community and Regional Planning Program Fall 12-5-2019 The Relationship between Separated Bicycle Lanes and Bicycle Crashes In Denver, Colorado. Wonsun Chang University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/arch_crp_theses Part of the Environmental Design Commons, Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Chang, Wonsun, "The Relationship between Separated Bicycle Lanes and Bicycle Crashes In Denver, Colorado." (2019). Community and Regional Planning Program: Student Projects and Theses. 57. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/arch_crp_theses/57 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Community and Regional Planning Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Community and Regional Planning Program: Student Projects and Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The relationship between separated bicycle lanes and bicycle crashes in Denver, Colorado. by Wonsun Chang A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Community and Regional Planning Major: Community and Regional Planning Under the Supervision of Professor Yunwoo Nam Lincoln, Nebraska December, 2019 THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SEPARATED BICYCLE LANES AND BICYCLE CRASHES IN DENVER, COLORADO. Wonsun Chang, MCRP University of Nebraska, 2019 Advisor: Yunwoo Nam Cyclists feel more comfortable when they ride in a bike facility separated from traffic. Therefore, cyclists tend to prefer separated bicycle lanes over other lanes. -

Don't Give up at the Intersection

Don’t Give Up at the Intersection Designing All Ages and Abilities Bicycle Crossings May 2019 NACTO Executive Board Working Group NACTO Project Team Janette Sadik-Khan Cara Seiderman Corinne Kisner Principal, Bloomberg Community Development Executive Director Associates Department, Cambridge, MA NACTO Chair Kate Fillin-Yeh Ted Wright Director of Strategy Seleta Reynolds New York City Department of General Manager, Los Angeles Transportation Nicole Payne Department of Transportation Program Manager, Cities for Cycling NACTO President Carl Sundstrom, P.E. New York City Department of Matthew Roe Robin Hutcheson Transportation Technical Lead Director of Public Works, City of Aaron Villere Minneapolis Peter Koonce, P.E. Senior Program Associate NACTO Vice President Portland Bureau of Transportation, Portland, OR Celine Schmidt Robert Spillar Design Associate Director of Transportation, City Mike Sallaberry, P.E. San Francisco Municipal of Austin Majed Abdulsamad Transportation Agency NACTO Treasurer Program Associate Michael Carroll Peter Bennett Deputy Managing Director, San José Department of Office of Transportation and Transportation, CA Technical Review Infrastructure Systems, City of Dylan Passmore, P.Eng. Philadelphia Joe Gilpin City of Vancouver, BC NACTO Secretary Alta Planning & Design David Rawsthorne, P.Eng. Joseph E. Barr Vignesh Swaminathan, P.E. City of Vancouver, BC Director, Traffic, Parking Crossroad Lab & Transportation, City of Dongho Chang, P.E. Cambridge Seattle Department of NACTO Affiliate Member Transportation Acknowledgments Representative This document was funded by a grant from the The John S. and James L. Advisory Committee Knight Foundation. NACTO Cities for Cycling Special thanks to Robert Boler from Committee representatives Austin, TX for providing the inspiration for the title of this document. -

Using Simulation to Assess Conflicts Between Bicyclists and Right-Turning Vehicles

Using Simulation to Assess Conflicts Between Bicyclists and Right-Turning Vehicles Eleni Christofa, PhD Michael Knodler, Jr., PhD Assistant Professor Professor Civil & Environmental Civil & Environmental Engineering Engineering UMass Amherst UMass Amherst Using Simulation to Assess Conflicts Between Bicyclists and Right-Turning Vehicles Eleni Christofa, PhD Aikaterini Deliali, MSc Assistant Professor Graduate Student Researcher Civil & Environmental Engineering Civil & Environmental Engineering University of Massachusetts Amherst University of Massachusetts Amherst https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8740-5558 https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7950-3185 Michael Knodler Jr., PhD Professor Civil & Environmental Engineering University of Massachusetts Amherst https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6517-4066 i A Report on Research SAFER-SIM University Transportation Center Federal Grant No: 69A3551747131 February 2019 DISCLAIMER The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the information presented herein. This document is disseminated in the interest of information exchange. The report is funded, partially or entirely, by a grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation’s University Transportation Centers Program. However, the U.S. Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof. ii Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................... iii List of Figures................................................................................................................. -

Massdot Separated Bike Lane Planning & Design Guide

4 INTERSECTION DESIGN This chapter provides key principles that should be used to develop and evaluate design approaches and treatments that will result in intersections that support all ages and abilities of bicyclists. This chapter illustrates the application of these principles for common intersection configurations which include protected intersections, roundabouts, mixing zones and driveway crossings. Intersection design also requires consideration of parking, loading and bus stops (see Chapter 5), and signal operations (see Chapter 6). 4.1 CONTEXT Safe and comfortable intersections a bicyclist’s path significantly affects availability of right-of-way and stopping minimize delays, reduce conflicts and bicyclists’ safety and comfort. Intersection location of the bus (in-lane versus bus bay; reduce the risk of injury for all users in the geometry and corner radius design affects as well as near-side, far-side and mid- event of a crash. Intersections include not the merging or turning speed of the block stop location) are factors that impact only bicycle crossings of streets, but also motorist. the design of separated bike lanes (see crossings with driveways, alleys, sidewalks, Chapter 5). shared use paths and other separated Bicyclists have operating characteristics bike lanes. Intersections are likely to be that are quite different from pedestrians. locations where bicyclists transition into The approach speed of a bicyclist TERRAIN operating in a separated bike lane is and out of separated bike lanes to other The existing terrain and sight conditions will typically between 10 and 15 mph on flat types of bikeway accommodations. These affect available sight lines and approach ground. This speed can be three to eight transitions should be intuitive to all users of speeds of bicyclists and motorists. -

Using Simulation to Assess and Reduce Conflicts Between Drivers and Bicyclists

Using Simulation to Assess and Reduce Conflicts between Drivers and Bicyclists Jodie M. Plumert, PhD Joseph K. Kearney, PhD Professor Professor Psychological and Brain Sciences Computer Science University of Iowa University of Iowa Using Simulation to Assess and Reduce Conflicts between Drivers and Bicyclists Jodie M. Plumert, BA, PhD Elizabeth E. O’Neal, PhD Professor Postdoc Psychological and Brain Sciences Psychological and Brain Sciences University of Iowa University of Iowa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2150-7922 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3934-4009 Joseph K. Kearney, BA, MA, MS, PhD Lakshmi Devi Subramanian, BS Professor PhD Student Computer Science Computer Science University of Iowa University of Iowa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0443-8152 https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5066-011X A Report on Research Sponsored by SAFER-SIM University Transportation Center Federal Grant No: 69A3551747131 April 2020 iii DISCLAIMER The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the information presented herein. This document is disseminated in the interest of information exchange. The report is funded, partially or entirely, by a grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation’s University Transportation Centers Program. However, the U.S. Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof. iv Table of Contents Table of Contents ..................................................................................................................... v List of Figures .......................................................................................................................