A Historical Perspective on the AASHTO Guide for The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dissecting the Safety Benefits of Protected Intersection Design Features

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Transportation Engineering Masters Projects Civil and Environmental Engineering 2019 DISSECTING THE SAFETY BENEFITS OF PROTECTED INTERSECTION DESIGN FEATURES Nicholas Campelll University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cee_transportation Part of the Transportation Engineering Commons Campelll, Nicholas, "DISSECTING THE SAFETY BENEFITS OF PROTECTED INTERSECTION DESIGN FEATURES" (2019). Transportation Engineering Masters Projects. 13. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cee_transportation/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Civil and Environmental Engineering at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transportation Engineering Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DISSECTING THE SAFETY BENEFITS OF PROTECTED INTERSECTION DESIGN FEATURES A Master’s Project Presented by NICHOLAS CAMPBELL Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN CIVIL ENGINEERING MASTER OF REGIONAL PLANNING May 2019 Dual Degree in Civil Engineering and Regional Planning ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many thanks are extended to my committee for their guidance and assistance throughout this process, special thanks to Dr. Michael Knodler Jr. and Dr. Mark Hamin for creating the dual degree path in Transportation Engineering and Regional Planning. A big thanks to those who helped me learn how the driving simulator works, especially Ganesh Pai Mangalore and Katerina Deliali. iii ABSTRACT DISSECTING THE PERFORMANCE SAFETY BENEFITS OF PROTECTED INTERSECTION DESIGN MAY 2019 NICHOLAS CAMPBELL, M.S.C.E, UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST MRP, UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST Directed by: Mark Hamin & Michael A. -

Cycling Safety: Shifting from an Individual to a Social Responsibility Model

Cycling Safety: Shifting from an Individual to a Social Responsibility Model Nancy Smith Lea A thesis subrnitted in conformity wR the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Sociology and Equity Studies in Education Ontario lnstitute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto @ Copyright by Nancy Smith Lea, 2001 National Library Bibliothbque nationale ofCanada du Canada Aoquieit-el services MbJiographiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pemiettant P. la National Library of Canada to BiblioWque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or oeîî reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette dièse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fihn, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propndté du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thése. thesis nor substantial exûacts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celîe-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement. reproduits sans son pemiission. almmaîlnn. Cycling Satety: Shifting from an Indhrldual to a Social Reaponribillty Modal Malter of Arts, 2001 Sociology and ~qultyStudie8 in Education Ontario Inrtltute for *die8 in- ducati ion ot the University of Toronto ABSTRACT Two approaches to urban cycling safety were studied. In the irrdividual responsibility rnodel, the onus is on the individual for cycling safety. The social responsibiiii model takes a more coliecthrist approach as it argues for st~cturallyenabling distriûuted respansibility. -

Guidance for Protected/Buffered Bike Lanes with Delineators: Literature Search July 6, 2017

Guidance for Protected/Buffered Bike Lanes with Delineators: Literature Search July 6, 2017 Prepared for: Marcus Bekele Prepared by: Karen Neinstadt Resources searched: Transport database, Web, MnDOT Library catalog, TRB Research in Progress Summary: This literature search reflects results on protected and/or buffered bike lanes. Sometimes the phrase, “cycle track” is also used. The term “delineator” was not consistent in the results but it is included where found and relevant. Most Relevant Results Michigan Street Protected Bike Lane Demonstration Project (Duluth-Superior Metropolitan Interstate Council) http://dsmic.org/study/pbl/ FHWA Separated Bike Lane Planning and Design Guide https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/bicycle_pedestrian/publications/separated_bikelane_pdg/page00.cfm Lessons from the Green Lanes: Evaluating Protected Bike Lanes in the U.S. https://bikeportland.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/NITC-RR-583_ProtectedLanes_FinalReportb.pdf Minneapolis is Breaking Bicycling Ground with New Protected Lanes: Here’s What’s Working https://www.minnpost.com/cityscape/2015/09/minneapolis-breaking-bicycling-ground-new-protected-lanes- here-s-what-s-working Understanding Bicycle Markings in Minneapolis: A Guide for Motorists and Bicyclists http://www.minneapolismn.gov/www/groups/public/@publicworks/documents/images/wcms1p-083551.pdf Minneapolis Plans Big Push for Protected Bike Lanes in City Core http://www.startribune.com/minneapolis-plans-big-push-for-protected-bike-lanes-in-city-core/294450161/ Bikeways for Everyone: Protected Bike Lanes http://www.bikewaysforeveryone.org/protected_bike_lanes Title: Using Simulation to Assess and Reduce Conflicts between Drivers and Bicyclists. URL: http://rip.trb.org/view/1459790 Abstract: Separated bicycle lanes, or cycle tracks, are increasing in popularity across the nation. -

Literature Review- Resource Guide for Separating Bicyclists from Traffic

Literature Review Resource Guide for Separating Bicyclists from Traffic July 2018 0 U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the use of the information contained in this document. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. The U.S. Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trademarks or manufacturers’ names appear in this report only because they are considered essential to the objective of the document. Technical Report Documentation Page 1. REPORT NO. 2. GOVERNMENT ACCESSION NO. 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NO. FHWA-SA-18-030 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. REPORT DATE Literature Review: Resource Guide for Separating Bicyclists from Traffic 2018 6. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION CODE 7. AUTHOR(S) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Bill Schultheiss, Rebecca Sanders, Belinda Judelman, and Jesse Boudart (TDG); REPORT NO. Lauren Blackburn (VHB); Kristen Brookshire, Krista Nordback, and Libby Thomas (HSRC); Dick Van Veen and Mary Embry (MobyCON). 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME & ADDRESS 10. WORK UNIT NO. Toole Design Group, LLC VHB 11. CONTRACT OR GRANT NO. 8484 Georgia Avenue, Suite 800 8300 Boone Boulevard, Suite 300 DTFH61-16-D-00005 Silver Spring, MD 20910 Vienna, VA 22182 12. SPONSORING AGENCY NAME AND ADDRESS 13. TYPE OF REPORT AND PERIOD Federal Highway Administration Office of Safety 1200 New Jersey Ave., SE Washington, DC 20590 14. SPONSORING AGENCY CODE FHWA 15. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES The Task Order Contracting Officer's Representative (TOCOR) for this task was Tamara Redmon. -

FHWA Bikeway Selection Guide

BIKEWAY SELECTION GUIDE FEBRUARY 2019 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave Blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED February 2019 Final Report 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. FUNDING NUMBERS Bikeway Selection Guide NA 6. AUTHORS 5b. CONTRACT NUMBER Schultheiss, Bill; Goodman, Dan; Blackburn, Lauren; DTFH61-16-D-00005 Wood, Adam; Reed, Dan; Elbech, Mary 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION VHB, 940 Main Campus Drive, Suite 500 REPORT NUMBER Raleigh, NC 27606 NA Toole Design Group, 8484 Georgia Avenue, Suite 800 Silver Spring, MD 20910 Mobycon - North America, Durham, NC 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) 10. SPONSORING/MONITORING AND ADDRESS(ES) AGENCY REPORT NUMBER Tamara Redmon FHWA-SA-18-077 Project Manager, Office of Safety Federal Highway Administration 1200 New Jersey Avenue SE Washington DC 20590 11. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 12a. DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY STATEMENT 12b. DISTRIBUTION CODE This document is available to the public on the FHWA website at: NA https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/ped_bike 13. ABSTRACT This document is a resource to help transportation practitioners consider and make informed decisions about trade- offs relating to the selection of bikeway types. This report highlights linkages between the bikeway selection process and the transportation planning process. This guide presents these factors and considerations in a practical process- oriented way. It draws on research where available and emphasizes engineering judgment, design flexibility, documentation, and experimentation. 14. SUBJECT TERMS 15. NUMBER OF PAGES Bike, bicycle, bikeway, multimodal, networks, 52 active transportation, low stress networks 16. PRICE CODE NA 17. SECURITY 18. SECURITY 19. SECURITY 20. -

Planning for Active Transportation in the Western United States: an Alternative Future for Cache Valley, Utah

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-2018 Planning for Active Transportation in the Western United States: An Alternative Future for Cache Valley, Utah Stephanie A. Tomlin Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Environmental Design Commons, and the Landscape Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Tomlin, Stephanie A., "Planning for Active Transportation in the Western United States: An Alternative Future for Cache Valley, Utah" (2018). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 7195. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7195 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PLANNING FOR ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION IN THE WESTERN UNITED STATES: AN ALTERNATIVE FUTURE FOR CACHE VALLEY, UTAH by Stephanie A. Tomlin A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Bioregional Planning Approved: Bartlett Warren-Kretzschmar, Ph.D. Richard Toth, M.L.A. Major Professor Committee Member Jordy Guth, M.S. Mark R. McLellan, Ph.D. Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2018 ii Copyright © Stephanie A. Tomlin, 2018 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Planning for Active Transportation in the Western United States: An Alternative Future for Cache Valley, Utah by Stephanie A. Tomlin, Master of Bioregional Planning Utah State University, 2018 Major Professor: Bartlett (Barty) Warren-Kretzschmar, Ph.D. -

Tennessee Traffic Laws Relating to Bicycles a HANDBOOK for MOTORISTS & BICYCLISTS

Tennessee Traffic Laws Relating to Bicycles A HANDBOOK FOR MOTORISTS & BICYCLISTS Suite 403, City County Building • 400 Main Street • Knoxville, Tennessee 37902 Telephone: 865 215-2500 • Fax: 865 215-2068 • E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.knoxtrans.org REFERENCES • Tennessee Code, www.lexis.com (all citations in this document are from the Tennessee Code, as of January 2006) About the Knoxville Regional Bicycle Program • Florida Bicycle Law Enforcement Guide, June 2004 The Knoxville Regional Transportation Planning Organization (TPO) • http://www.bicyclinginfo.org/ee/enforcement.htm, December 2005 coordinates a comprehensive, multi-modal transportation planning process for the Knoxville urban area. Members include: Cities of Alcoa, Knoxville and Maryville, Town of Farragut, Lenoir City, Blount, Knox, Loudon, and Sevier Counties, Tennessee Department of Transportation, and East Tennessee Development District. As a component of the TPO, the Knoxville Regional Bicycle Program envisions a convenient, effi cient transportation system where people can bike safely to all destinations. Bicycling is a great way to get around town. It saves money, improves air quality and is good exercise. The purpose of the Bicycle Program is to integrate bicycling into the transportation system. The program works with all City and County departments within the TPO boundary to implement the Regional Bicycle Plan. Nationwide, communities are realizing they cannot build their way out of congestion. They must look to other solutions, such as transit, carpooling and bicycling. A healthy transportation system provides safe, convenient choices. Improving bicycling conditions provides alternatives for the increasing numbers of citizens who can’t afford, don’t want to or are physically unable to drive motor vehicles. -

Contextual Guidance at Intersections for Protected Bicycle Lanes

Portland State University PDXScholar Transportation Research and Education Center TREC Final Reports (TREC) 12-1-2019 Contextual Guidance at Intersections for Protected Bicycle Lanes Christopher M. Monsere Portland State University, [email protected] Nathan McNeil Portland State University Yi Wang Portland State University Rebecca Sanders Toole Design Group Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/trec_reports Part of the Transportation Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Monsere, C., N. McNeil, Y. Wang, R. Sanders, R. Burchfield and .W Schultheiss. Contextual Guidance at Intersections for Protected Bicycle Lanes. Final Report. NITC-RR- 987. Portland, OR: Transportation Research and Education Center (TREC), November 2019. https://dx.doi.org/10.15760/trec.241 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in TREC Final Reports by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Final Report 987 December 2019 Contextual Guidance at Intersections for Protected Bicycle Lanes Chris Monsere, Ph.D. Nathan McNeil, M.U.R.P. Yi Wang, Ph.D. Rebecca Sanders, Ph.D. Robert Burchfield, P.E. William Schultheiss, P.E. NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNITIES nitc-utc.net CONTEXTUAL GUIDANCE AT INTERSECTIONS FOR PROTECTED BICYCLE LANES Final Report NITC-RR-987 by Christopher Monsere Nathan McNeil Yi Wang Portland State University Rebecca Sanders Robert Burchfield William Schultheiss Toole Design Group for National Institute for Transportation and Communities (NITC) P.O. Box 751 Portland, OR 97207 December 2019 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. -

Bike Boom Bike Boom

BIKE CARLTON REID BOOM BOOM THE UNEXPECTED RESURGENCE OF CYCLING BIKE Island Press’ mission is to provide the best ideas and information to those seeking to understand and protect the environment and create solutions to its complex problems. Join our newsletter to get the latest news on authors, events, and free book giveaways. Click here to join now! BIKE BOOM BIKE BOOM The Unexpected Resurgence of Cycling CARLTON REID Washington | Covelo | London © 2017 Carlton Reid All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher: Island Press, 2000 M St., NW, Suite 650, Washington, DC 20036 ISLAND PRESS is a trademark of the Center for Resource Economics. Library of Congress Control Number: 2016959951 Text design by Maureen Gately Typesetting by Carlton Reid Websites: islandpress.org & bikeboom.info Printed on recycled, acid-free paper Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Keywords: Bicycle infrastructure; bike path; bikeway; Columbia, Maryland; cycleways; Davis, California; the Netherlands; New York City; shared streets; Stevenage, UK; vehicular cycling; Victory Bikes About the Cover Image “Power to the pedal!” “Cycling helps build healthy bodies,” asserted one placard. “Give Mom a bike lane,” pleaded another. One held aloft by a young woman in stylish full- fingered red gloves with a matching satchel that simply said “PEDAL!” The placards were real, the San Francisco demonstration was real, but the pretty woman in the striking white dress and red accessories was a model, and the bike she was sat astride for this 1970s “Bike-in” was not hers, but one supplied by a local bicycle shop. -

Designing for On-Road Bikeways

Designing for Bicyclist Safety Module B DESIGNING ON-ROAD BIKEWAYS LEARNING OUTCOMES Describe features of on-road bikeways Select design criteria for on-road bikeways in various contexts BICYCLE CHARACTERISTICS BICYCLE CHARACTERISTICS Height Handlebar - 36-44 in Eye - 60 in Operating - 100 in Width Physical – 30 in Minimum operating – 48 in Preferred operating – 60 in OLDER BIKEWAY TYPES “Bike Route” “Bike Path” Neither term is clear They are all bikeways BIKEWAY NETWORK Just like roads and sidewalks, bikeways need to be part of an connected network Combine various types, including on and off-street facilities HIERARCHY OF BIKEWAYS Shared-Use Paths Separated Bike Lanes Bike Lanes Shoulders Shared Roadway Photo by Harvey Muller Photo by SCI Photo by Harvey Muller Photo by SCI Designing On-Road Bikeways SHARED ROADWAY Photo by Harvey Muller SHARED ROADWAY Most common— roads as they are Appropriate on low-volume or low-speed 85% or more of a well-connected grid SHARED LANES Unless prohibited, all roads have shared lanes No special features for: Minor roads Low volumes (< 1000 vpd) Speeds vary (urban v. rural) SHARED LANES Supplemental features Pavement markings or “sharrows” Detectors & signal timing SHARED LANE MARKING Lateral position Connect gaps in bike lanes Roadway too narrow for passing Position in intersections & transitions SHARED ROAD SIGNS Ride side-by-side? Chase bicyclist? Warning or regulation? Opposite forces? Philadelphia, PA ...and who “shares”? New Orleans, LA California SHARED ROAD SIGNS -

Listening to Bike Lanes: Abstract

Listening to Bike Lanes: Abstract Hiles > Essays > Listening > Listening to Bike Lanes: Moving Beyond the Feud by Jeffrey A. Hiles, 1996 Abstract One group of bicycle advocates insists that cities need special facilities to separate bicyclists from motor traffic and make cycling less intimidating. Another group argues that such an approach compromises bicyclists’ safety by putting riders at odds with traffic, and that the best way to help cyclists ride safely and confidently is through cyclist training. In recent years, many in the first group have embraced bike lanes as their preferred type of facility. The second group rallies around a League of American Bicyclists’ training program called Effective Cycling. This paper critically reviews the claims of advocates on each side of this controversy and finds that what passes for hard fact is often conjecture and exaggeration, including assertions about car-bike crashes, and the potential of both bike lanes and education to affect bicyclist safety and behavior. In an effort to find a less one-sided viewpoint, the author employs concepts from the fields of cognitive psychology and environmental design to explore alternative ways of describing and explaining how bicyclists and motorists are influenced by the environments through which they move. The author recommends steps that bicycle transportation advocates can take to help them move beyond simplistic beliefs that heat arguments over bike lanes: Move away from theories that equate bicyclists’ skill and experience with their comfort in traffic, and toward a philosophy that respects as normal and natural a range of traffic tolerance. Realize that this “folk transportation” is guided by many intuitive factors and that advocacy philosophies that rely heavily on getting bicyclists to behave ideally are not in tune with this reality. -

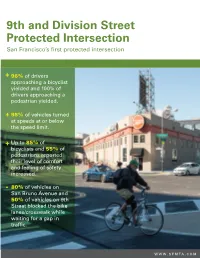

9Th and Division Street Protected Intersection San Francisco’S First Protected Intersection

9th and Division Street Protected Intersection San Francisco’s first protected intersection + 96% of drivers approaching a bicyclist yielded and 100% of drivers approaching a pedestrian yielded. + 98% of vehicles turned at speeds at or below the speed limit. + Up to 85% of bicyclists and 55% of pedestrians reported their level of comfort and feeling of safety increased. - 80% of vehicles on San Bruno Avenue and 50% of vehicles on 9th Street blocked the bike lanes/crosswalk while waiting for a gap in traffic. WWW.SFMTA.COM Division Street is a key east-west corridor Project Location for people biking to Caltrain, the Mission 9th Street and Division Street District, AT&T Ballpark, and the South Beach Date of Implementation area. However, in the past five years there December 2016 were 106 collisions along the Division Street Project Elements Protected Intersectioncorridor, Design including two traffic at deaths. Division – Buffered Street and parking-protected & bike 9thlanes Street – Raised crosswalks To increase safety and comfort in the area, – New sidewalk along the west side of 9th the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Street – Painted safety zones and low concrete Agency (SFMTA) implemented a protected elements intersection at the 9th Street/Division Street/ San Bruno Avenue intersection. This location Key Evaluation Metrics – Vehicle Approach Speed is San Francisco’s first implementation of the – Conflict Behavior at Key Locations protected intersection design concept. – Yielding Rates – Perception of Safety 9 th S eet tr Str e e an t n an Br Buered Bike Lanes Two-Way Street Pedestrian Safety Island New Sidewalk Perpendicular Parking Raised Crossing Division Street Parking Protected Bikeway Division Street Painted Safety Zones V e r Raised Crossing m o n t S t r e e Sa t n P B o Corner Safety Island r t u r e n r o o A A v v enu e n u 9th Street/Division Street Protected Intersection e e SFMTA.COM Division/13th Street Safety Project For more information, please contact Will Tabajonda at [email protected].