Conflict and Complexity: Army and Gentry in Interregnum Herefordshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549

“JUST AS THE PRIESTS HAVE THEIR WIVES”: PRIESTS AND CONCUBINES IN ENGLAND, 1375-1549 Janelle Werner A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Advisor: Professor Judith M. Bennett Reader: Professor Stanley Chojnacki Reader: Professor Barbara J. Harris Reader: Cynthia B. Herrup Reader: Brett Whalen © 2009 Janelle Werner ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JANELLE WERNER: “Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549 (Under the direction of Judith M. Bennett) This project – the first in-depth analysis of clerical concubinage in medieval England – examines cultural perceptions of clerical sexual misbehavior as well as the lived experiences of priests, concubines, and their children. Although much has been written on the imposition of priestly celibacy during the Gregorian Reform and on its rejection during the Reformation, the history of clerical concubinage between these two watersheds has remained largely unstudied. My analysis is based primarily on archival records from Hereford, a diocese in the West Midlands that incorporated both English- and Welsh-speaking parishes and combines the quantitative analysis of documentary evidence with a close reading of pastoral and popular literature. Drawing on an episcopal visitation from 1397, the act books of the consistory court, and bishops’ registers, I argue that clerical concubinage occurred as frequently in England as elsewhere in late medieval Europe and that priests and their concubines were, to some extent, socially and culturally accepted in late medieval England. -

By Flichard William Evans

Thn Elrhteanth Contury Walsh AwnIcaninR With Its Relationships To Tho Contemporary English EynnirelicalI Revtval by flichard William Evans A Thesis submitted to the ]Faculty of Divinity of the University of Edinburgh In partial fulfilment of the roquirements for tho Doctor of Philosophy degree. t41v 19.96 HELEN FY, Annwyl BrIod, Am ol aerch all chofronaoth "The linos are fallen unto me In pleasant places; yen# I have-a goodly heritage. " Psalm M6 "One of the most discreditable and discourteous things in life is contompt for that which we once loved. " Adam C. Welch. CONTENTS Chapter Pace Prefaco Introduction A Sketchi Religion In Wales Before The Methodist Awakening 24 .......... Beginnings Of An Epoch 42' Part 1 ..... Part 2 54 ..... o.,. o ... III. Early Relationships ................ 72 IV. Orpanising Against Porils. 102 e. oo.... ......... o V., Lower-Lovel Relationships.. 130 o. oo ........ ooo*o V1. The Separation 170 ......... ..... VII. The 197 APPRIMICES A Deciding Upqn A Name 22.5 ................. ******* The Groat B Association ...................... 226 John Jones 227 C .................................. D An Indirect Influence 20,28 ...................... E Trovecka Family Side-Lights 230 P Harris's Varied Interests 233 Contemporary Opinions 235 0 H The Two Trevacka Colleges 236 ............ Bibliography 23a ....... MAP Places Connected With the 18th Century Awakening Prontlapiece in Wales II. (Tho brokon lino indicates my route through the country of the revivalists) LIST OF ILLUSTRATICTIS Following page A Papo from tho Diary of Howell Harris 13 Tho Wolsh Revivalists 53 lowornois" 61 "Pantycelyn" 64 The Trovacka'Buildings (1042) 199 The map and illustrations have been made available through the courtosy of the National Library of Wales. -

Brycheiniog Vol 42:44036 Brycheiniog 2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 1

68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 1 BRYCHEINIOG Cyfnodolyn Cymdeithas Brycheiniog The Journal of the Brecknock Society CYFROL/VOLUME XLII 2011 Golygydd/Editor BRYNACH PARRI Cyhoeddwyr/Publishers CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG A CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY AND MUSEUM FRIENDS 68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 2 CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG a CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY and MUSEUM FRIENDS SWYDDOGION/OFFICERS Llywydd/President Mr K. Jones Cadeirydd/Chairman Mr J. Gibbs Ysgrifennydd Anrhydeddus/Honorary Secretary Miss H. Gichard Aelodaeth/Membership Mrs S. Fawcett-Gandy Trysorydd/Treasurer Mr A. J. Bell Archwilydd/Auditor Mrs W. Camp Golygydd/Editor Mr Brynach Parri Golygydd Cynorthwyol/Assistant Editor Mr P. W. Jenkins Curadur Amgueddfa Brycheiniog/Curator of the Brecknock Museum Mr N. Blackamoor Pob Gohebiaeth: All Correspondence: Cymdeithas Brycheiniog, Brecknock Society, Amgueddfa Brycheiniog, Brecknock Museum, Rhodfa’r Capten, Captain’s Walk, Aberhonddu, Brecon, Powys LD3 7DS Powys LD3 7DS Ôl-rifynnau/Back numbers Mr Peter Jenkins Erthyglau a llyfrau am olygiaeth/Articles and books for review Mr Brynach Parri © Oni nodir fel arall, Cymdeithas Brycheiniog a Chyfeillion yr Amgueddfa piau hawlfraint yr erthyglau yn y rhifyn hwn © Except where otherwise noted, copyright of material published in this issue is vested in the Brecknock Society & Museum Friends 68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 3 CYNNWYS/CONTENTS Swyddogion/Officers -

POLITICS, SOCIETY and CIVIL WAR in WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History

Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History Series editors ANTHONY FLETCHER Professor of History, University of Durham JOHN GUY Reader in British History, University of Bristol and JOHN MORRILL Lecturer in History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow and Tutor of Selwyn College This is a new series of monographs and studies covering many aspects of the history of the British Isles between the late fifteenth century and the early eighteenth century. It will include the work of established scholars and pioneering work by a new generation of scholars. It will include both reviews and revisions of major topics and books which open up new historical terrain or which reveal startling new perspectives on familiar subjects. It is envisaged that all the volumes will set detailed research into broader perspectives and the books are intended for the use of students as well as of their teachers. Titles in the series The Common Peace: Participation and the Criminal Law in Seventeenth-Century England CYNTHIA B. HERRUP Politics, Society and Civil War in Warwickshire, 1620—1660 ANN HUGHES London Crowds in the Reign of Charles II: Propaganda and Politics from the Restoration to the Exclusion Crisis TIM HARRIS Criticism and Compliment: The Politics of Literature in the Reign of Charles I KEVIN SHARPE Central Government and the Localities: Hampshire 1649-1689 ANDREW COLEBY POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, i620-1660 ANN HUGHES Lecturer in History, University of Manchester The right of the University of Cambridge to print and sell all manner of books was granted by Henry VIII in 1534. -

ROBERT GERAINT GRUFFYDD Robert Geraint Gruffydd 1928–2015

ROBERT GERAINT GRUFFYDD Robert Geraint Gruffydd 1928–2015 GERAINT GRUFFYDD RESEARCHED IN EVERY PERIOD—the whole gamut—of Welsh literature, and he published important contributions on its com- plete panorama from the sixth to the twentieth century. He himself spe- cialised in two periods in particular—the medieval ‘Poets of the Princes’ and the Renaissance. But in tandem with that concentration, he was renowned for his unique mastery of detail in all other parts of the spec- trum. This, for many acquainted with his work, was his paramount excel- lence, and reflected the uniqueness of his career. Geraint Gruffydd was born on 9 June 1928 on a farm named Egryn in Tal-y-bont, Meirionnydd, the second child of Moses and Ceridwen Griffith. According to Peter Smith’sHouses of the Welsh Countryside (London, 1975), Egryn dated back to the fifteenth century. But its founda- tions were dated in David Williams’s Atlas of Cistercian Lands in Wales (Cardiff, 1990) as early as 1391. In the eighteenth century, the house had been something of a centre of culture in Meirionnydd where ‘the sound of harp music and interludes were played’, with ‘the drinking of mead and the singing of ancient song’, according to the scholar William Owen-Pughe who lived there. Owen- Pughe’s name in his time was among the most famous in Welsh culture. An important lexicographer, his dictionary left its influence heavily, even notoriously, on the development of nineteenth-century literature. And it is strangely coincidental that in the twentieth century, in his home, was born and bred for a while a major Welsh literary scholar, superior to him by far in his achievement, who too, for his first professional activity, had started his career as a lexicographer. -

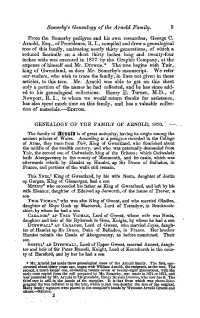

Jsomerby's Genealogy Ofthe Arnold Family. from the Somerby Pedigree

JSomerby's Genealogy ofthe Arnold Family. 9 From the Somerby pedigree and his own researches, George C. Arnold, Esq., of Providence, R.1., compiled and drew a genealogical tree of this family, embracing nearly thirty generations, of which a reduced facsimile on a sheet thirty inches long and twenty-four inches wide was executed in 1877 by the Graphic Company, at the expense of himself and Mr.Drowne.* The tree begins with Xnir, king of Gwentland, as does Mr.Somerby's manuscript. We refer our. readers, who wish to trace the family, inlines not given inthese articles', to this tree. Mr. Arnold was able to get on this sheet only a portion of the names he had collected, and he has since add- ed to his genealogical collections. Henry E. M.D., of Newport, R.1., to whom we would return thanks- for assistance, has also spent much time oh this family, and has a valuable collec- tion of materials. —Editor. GENEALOGY OF THE FAMILYOF ARNOLD, 1870. The family of £KtnOltt is ofgreat antiquity, having its origin among the ancient princes of Wales. According to a pedigree recorded inthe College of Arms, they trace from Tnir,King of Gwentland, who flourished about the middle of the twelfth century, and who was paternally descended from Ynir,the second son of Cadwaladr, king of the Britons ; which Cadwaladr built Abergavenny in the county of Monmouth, and its castle, which was afterwards rebuilt by Hamlet ap Hamlet, ap Sir Druce of Balladon, in France, and portions of the walls stillremain. This Ynir,1 Kingof Gwentland, by his wife Nesta, daughter of Jestin -

Chapter VIII Witchcraft As Ma/Efice: Witchcraft Case Studies, the Third Phase of the Welsh Antidote to Witchcraft

251. Chapter VIII Witchcraft as Ma/efice: Witchcraft Case Studies, The Third Phase of The Welsh Antidote to Witchcraft. Witchcraft as rna/efice cases were concerned specifically with the practice of witchcraft, cases in which a woman was brought to court charged with being a witch, accused of practising rna/efice or premeditated harm. The woman was not bringing a slander case against another. She herself was being brought to court by others who were accusing her of being a witch. Witchcraft as rna/efice cases in early modem Wales were completely different from those witchcraft as words cases lodged in the Courts of Great Sessions, even though they were often in the same county, at a similar time and heard before the same justices of the peace. The main purpose of this chapter is to present case studies of witchcraft as ma/efice trials from the various court circuits in Wales. Witchcraft as rna/efice cases in Wales reflect the general type of early modern witchcraft cases found in other areas of Britain, Europe and America, those with which witchcraft historiography is largely concerned. The few Welsh cases are the only cases where a woman was being accused of witchcraft practices. Given the profound belief system surrounding witches and witchcraft in early modern Wales, the minute number of these cases raises some interesting historical questions about attitudes to witches and ways of dealing with witchcraft. The records of the Courts of Great Sessions1 for Wales contain very few witchcraft as rna/efice cases, sometimes only one per county. The actual number, however, does not detract from the importance of these cases in providing a greater understanding of witchcraft typology for early modern Wales. -

THE SKYDMORES/ SCUDAMORES of ROWLESTONE, HEREFORDSHIRE, Including Their Descendants at KENTCHURCH, LLANCILLO, MAGOR & EWYAS HAROLD

Rowlestone and Kentchurch Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study THE SKYDMORES/ SCUDAMORES OF ROWLESTONE, HEREFORDSHIRE, including their descendants at KENTCHURCH, LLANCILLO, MAGOR & EWYAS HAROLD. edited by Linda Moffatt 2016© from the original work of Warren Skidmore CITATION Please respect the author's contribution and state where you found this information if you quote it. Suggested citation The Skydmores/ Scudamores of Rowlestone, Herefordshire, including their Descendants at Kentchurch, Llancillo, Magor & Ewyas Harold, ed. Linda Moffatt 2016, at the website of the Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com'. DATES • Prior to 1752 the year began on 25 March (Lady Day). In order to avoid confusion, a date which in the modern calendar would be written 2 February 1714 is written 2 February 1713/4 - i.e. the baptism, marriage or burial occurred in the 3 months (January, February and the first 3 weeks of March) of 1713 which 'rolled over' into what in a modern calendar would be 1714. • Civil registration was introduced in England and Wales in 1837 and records were archived quarterly; hence, for example, 'born in 1840Q1' the author here uses to mean that the birth took place in January, February or March of 1840. Where only a baptism date is given for an individual born after 1837, assume the birth was registered in the same quarter. BIRTHS, MARRIAGES AND DEATHS Databases of all known Skidmore and Scudamore bmds can be found at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com PROBATE A list of all known Skidmore and Scudamore wills - many with full transcription or an abstract of its contents - can be found at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com in the file Skidmore/Scudamore One-Name Study Probate. -

Hlhs Herefordshire Local History Societies

HLHS HEREFORDSHIRE LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETIES Events, news, reviews September – November 2017 No.14 Editor: Margot Miller – Fownhope [email protected] Re-Enactment of Battle of Mortimers Cross 1461 9 and 10 September – Saturday & Sunday - Croft Castle NT Closing day for news & events for January 2018 HLHS emailing - Friday 15 December 2017 In this emailing: HARC events; Rotherwas Royal Ordnance Project & Kate Adie at the Courtyard Theatre; River Voices – oral history from the banks of the Wye; Shire Hall Centenary; Herefordshire Heritage Open Days; Rotherwas Chapel; Michaelchurch Court, St Owens Cross; Ashperton Heritage Trail; h.Art church exhibitions – Llangarron, Kings Caple & Hoarwithy; Mortimer History Society Symposium; Wigmore Centre public meeting; Re-Enactment of Battle of Mortimers Cross, Ross Walking Festival; WEA Autumn Courses, Hentland Conservation Project, Hereford Cathedral Library lectures and Cathedral Magna Carta exhibition; Woolhope Club visits; The Master’s House, Ledbury; Autumn programmes from history group - Bromyard, Eaton Bishop, Fownhope, Garway, Leominster, Longtown, Ross-on-Wye; David Garrick Anniversary Study Day at Hereford Museum Resource & Learning Centre, Friar Street. HARC EVENTS SEPTEMBER to NOVEMBER 2017 HARC, Fir Tree Lane, HR2 6LA, [email protected] 01432.260750 Booking: to reserve a place, all bookings in advance by email, phone or post Brochure of all upcoming events available by email or snail mail Friday 1st September: Rhys Griffith on Unearthing your Herefordshire Roots - a beginners guide on how to research your family history. 10.30-11.30am £6 Friday 15 September: Philip Bouchier – Behind the Scenes Tour 2-3pm £6 Monday 25 September: Philip Bouchier – Discovering the records of Hereford Diocese 10.30am-12.30pm £9.60 Wednesday 27 September: Elizabeth Semper O’Keefe - Anno Domini: an instruction to dating systems in archival documents. -

Cromwelliana the Journal of the Cromwell Association

Cromwelliana The Journal of The Cromwell Association 1999 • =-;--- ·- - ~ -•• -;.-~·~...;. (;.,, - -- - --- - -._ - - - - - . CROMWELLIANA 1999 The Cromwell Association edited by Peter Gaunt President: Professor JOHN MORRILL, DPhil, FRHistS Vice Presidents: Baron FOOT of Buckland Monachorum CONTENTS Right Hon MICHAEL FOOT, PC Professor IV AN ROOTS, MA, FSA, FRHistS Cromwell Day Address 1998 Professor AUSTIN WOOLRYCH, MA, DLitt, FBA 2 Dr GERALD AYLMER, MA, DPhil, FBA, FRHistS By Roy Sherwood Miss PAT BARNES Mr TREWIN COPPLESTONE, FRGS Humphrey Mackworth: Puritan, Republican, Cromwellian Chairman: Dr PETER GAUNT, PhD, FRHistS By Barbara Coulton 7 Honorary Secretary: Mr Michael Byrd Writings and Sources III. The Siege. of Crowland, 1643 5 Town Fann Close, Pinchbeck, near Spalding, Lincolnshire, PEI I 3SG By Dr Peter Gaunt 24 Honorary Treasurer: Mr JOHN WESTMACOTT Cavalry of the English Civil War I Salisbury Close, Wokingham, Berkshire, RG41 4AJ I' By Alison West 32 THE CROMWELL ASSOCIATION was founded in 1935 by the late Rt Hon Isaac Foot and others to commemorate Oliver Cromwell, the great Puritan statesman, and to Oliver Cromwell, Kingship and the encourage the study of the history of his times, his achievements and influence. It is Humble Petition and Advice neither political nor sectarian, its aims being essentially historical. The Association By Roy Sherwood 34 seeks to advance its aims in a variety of ways which have included: a. the erection of commemorative tablets (e.g. at Naseby, Dunbar, Worcester, Preston, etc) (From time to time appeals are made for funds to pay for projects of 'The Flandric Shore': Cromwellian Dunkirk this sort); By Thomas Fegan 43 b. helping to establish the Cromwell Museum in the Old Grammar School at Huntingdon; Oliver Cromwell c. -

The Life of Dr. George Bull, Lord Bishop of St

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com i NIVERSSTY OF MICHIGAN LIBRARIES jw: V "\ THE LIFE OF DR. GEORGE BULL, LORD BISHOP OF ST. DAVIDS. THE LIFE OF DR. GEORGE BULL, LORD BISHOP OF ST. DAVID'S; WITH THE HISTORY OF THOSE CONTROVERSIES IN WHICH HE WAS ENGAGED : AND AN ABSTRACT OF THOSE FUNDAMENTAL DOCTRINES Which he maintained and defended in the Latin tongue. BY OBERT NELSON, Esq. A NEW EDITION. OXFORD, PRINTED BY W. BAXTER ; FOR J. PARKER : AND LAW AND WHITTAKER J AND OGLES, DUNCAN, AND COCHRAN, LONDON. 1816. 5'< /<?<? » .»**> I Bib l&stte-fio CONTENTS. INTRODUCTION. -I HE occasion of writing the Life, p. 1. An apology for attempting it, ibid. His own reputation secured by his works, 2. Why it may be acceptable to learned and good men, 3. Reasons for the length of it, 4. I. When and where Mr. Bull was born, 5. His family and parentage, ibid. Early dedicated to the service of the church, 6. II. Educated at Tiverton school in Devonshire, 7. An ac count and character of his master, 8. His great and early progress in classic learning, ibid. III. Removed to Exeter college in Oxford, 9. Taken notice of by two great men, 10. Acquainted with Mr. Clifford, afterwards Lord High Treasurer, 11. IV. He retires from Oxford, upon refusing the Engagement, 12. He goes with his tutor, Mr. Ackland, to North- Cadbury, 13. -

Recording, Reporting and Printing the Cromwellian 'Kingship Debates'

1 Recording, Reporting and Printing the Cromwellian ‘Kingship Debates’ of 1657. Summary: This article explores the problem of recovering early modern utterances by focusing upon the issue of how the ‘kingship debates’ of 1657 between Oliver Cromwell and a committee of ninety-nine MPs came to be recorded, reported and printed. Specifically, it investigates the two key records of the kingship debates which, despite being well known to scholars, have extremely shady origins. Not only does this article demonstrate the probable origins of both sources, by identifying the previously unknown scribe of one of them it also points to the possible relationship between the two. It also questions whether the nature of the surviving sources has exacerbated certain interpretations about the kingship debates and their outcome. To hear Oliver Cromwell speak could be an infuriating experience. Those members of the committee of ninety-nine MPs that filed out of Whitehall on 20 April 1657, after their fourth meeting with Cromwell in little over a week, would certainly have thought so. Appointed by the second Protectorate Parliament to convince him to accept their offer of kingship, the members of the committee hoped for a direct and positive answer from the Lord Protector. They had none. According to the parliament’s diarist, and member of the committee, Thomas Burton, they received from Cromwell ‘nothing but a dark speech, more promiscuous then before’ and returned thoroughly ‘unsatisfyed’.1 Historians of the Protectorate must share Burton’s frustrations in their struggle to penetrate Cromwell’s utterances. Yet, while Burton and his fellow MPs had the pleasure (or agony) of listening to Cromwell directly the historian must work from what are, at best, ear-witness accounts.