HEREFORDSHIRE Is Repeatedly Referred to in Domesday As Lying In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glenside, the Bage, Dorstone, Herefordshire HR3

Glenside, The Bage, Dorstone, Herefordshire HR3 5SU Description Utility Room 2.34m x 3.17m (7’8” x 10’5”) With a sink unit, plumbing for a washing A delightful detached former farmhouse set in a machine, space for a tumble dryer. popular part of Herefordshire set in approx. 1 acre. The accommodation has been much Kitchen/Breakfast Room 7.41m x 4.06m improved, having been newly redecorated (24’4” x 13’4”) throughout and benefits from central heating Two window seats, fitted kitchen units with solid and double glazing with brand new timber worktops, wooden doors and drawers, two-oven double glazed windows in part. oil-fired “Aga”, Calor Gas hob, a stainless steel The accommodation briefly comprises; Porch, sink, window to the front, space for an integral Kitchen/Breakfast Room, Dining Room, Sitting microwave, space for a dishwasher and under Room, Study, Snug/Playroom, Utility Room, Sun counter fridge and laminate floor tiles. Room/Boot Room, Boiler Room and WC. To the Dining Room 4.3m x 4.59m (14’1” x 15’1”) Glenside, first floor there are 2 double Bedrooms, a single With two windows to the front a wood-burning bedroom and a Shower Room and on the second The Bage, stove, a fireplace and an opening into - floor 2 double Bedrooms, one accessed off the Dorstone, other. Sitting Room 3.64m x 4.53m (11’11” x Herefordshire Situation 14’10”) With a former fireplace, windows to the front HR3 5SU The Bage is a small rural Hamlet found just and side aspects, and an alcove with fitted under a mile to the west of Dorstone Village, a shelving. -

Herefordshire News Sheet

CONTENTS EDITORIAL ........................................................................................................................... 2 ARS OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE FOR 1986 ...................................................................... PROGRAMME APRIL-SEPTEMBER 1986 ........................................................................... 3 FIELD MEETING AT KINGS CAPLE, MARCH 10TH 1985 ..................................................... 3 FIELD MEETING, SUNDAY JULY 21ST 1985 ........................................................................ 5 BRECON GAER, ABERYSCIR, POWYS .............................................................................. 6 WORKERS’ EDUCATION ASSOCIATION AND THE LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETIES IN HEREFORDSHIRE – NINTH ANNUAL DAY SCHOOL ......................................................... 8 TWYN-Y-GAER, PENPONT ................................................................................................. 8 A CAREER IN RUINS … ...................................................................................................... 9 ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH SECTION 1985 ............................................................. 13 NEWS ITEM FROM THE CRASWALL GRANDMONTINE SOCIETY ................................. 14 THE HEREFORDSHIRE FIELD NAME SURVEY ............................................................... 14 FIELD NAMES COPIED FROM THE PARISH TITHE MAP ................................................ 16 HAN 45 Page 1 HEREFORDSHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL NEWS WOOLHOPE CLUB ARCHAEOLOGICAL -

Herefordshire. [ Kelly's

186 BAT HEREFORDSHIRE. [ KELLY'S Batten William Knott, 2 Stanley villas, Birch John, 9 Holmer road, Hereford Brain Howard, Albany viI. Ashfield,Ross Ryelands street, Hereford Birchley Misses, ColwaIl cottage, Col- Braithwaite Misses, 3 Greenfield villas, BaughanJ.West view,W.Malvern,Mlvrn wall, Malvern Portfields, Here;ord Bayley Rev. Robert Burges, Rectory, Bird Rev. Reginald Hereford M.A. Brendon Mrs. Suffolk house, Glo'ster Castle Frome, Ledbury Rectory, Thruxton, Hereford road, Ross Bayley George Sheppard, BarroIl house, Bird Charles, Pavin, Drybridge, St. BrewerChas.I3 Perseverance rd. Lmnstr St. Owen street, Hereford Martin's street, Hereford Bridges Rev. Charles M.A. Rectory, Baylis Miss, Homend street, Ledbury Bird Ebenezer, Belmont, Kington Bredenbury, Worcester Baylis William, Overbury lodge, Ayle- Bird Mrs. 35 White Cross rd. Hereford Bridges George, 19 Bridge st. Kington stone hill, Hereford Bishop Rev. Rhys M.A. Rectory, Let- Bridges Samuel, Water view, Cantilupe Baynton Harry, 34 Harold st. Hereford ton RS.O street, Hereford Bazley John Worcester rd. Leominster Bishop Mrs. Brooklands, Dorstone, BridgwaterMrs. Old hall, Eyton,Lmnstr Beard Rev. Joseph, Peterchurch RS.O Peterchurch RS.O Brierly Rev. Joseph HenryM.A. Rector, Beard Mrs. Priory house, Widemarsh Bishop Mrs. 7 WhiteHorse st. Hereford Whitbourne, Worcester common, Hereford Black Rev. Charles M.A. The Elms, BrierleyMrs.PeI1rose cot.FownhopeHrfrd BeauchampF.W.St.Olave's,Colwll.Mlvrn Colwall green, Colwall, Malvern Bright Benj. Barton ct.Colwall, Malvern Beavan Rev. Thomas Meredith M.A. Black A. Campbell, Birch lodge, Much Britten William Edward, Edenhurst, Vicarage, Woolhope, Hereford Birch, Tram Inn RS.O Bodenham road, HereforJ BeavanJohn Griffith J.P. Penrhos court, Blacklock Mrs. -

2 Brighton Villas, Colwall, Nr Malvern, Worcestershire

2 Brighton Villas, Colwall, Nr Malvern, Worcestershire Courtyard Imposing semi-detached Victorian townhouse, situated in a desirable village location Garden LOCATION Malvern 3 miles, Ledbury 5 miles, Worcester 10 miles, Hereford 18½ miles, Gloucester 20 miles, Cheltenham 32 miles, Birmingham 40 miles Road: M50 (Jct 2) 9 miles, M5 (Jct 8) 21 miles Railway: Colwall, Ledbury, Malvern Airport: Birmingham (47 miles), Bristol (55 miles) SUMMARY OF FEATURES: • Substantial Victorian townhouse offering spacious accommodation • 5 bedrooms and 2 bathrooms, situated over two floors • 2 reception rooms, fitted kitchen, utility/storage room • Pocket garden to the front and courtyard garden to rear of property • Off road parking space SITUATION The property is situated in the desirable village of Colwall on the western side of the Malvern Hills, which are an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. This impressive property is well- situated in an area that offers a sought-after rural quality of life, yet is within easy reach of Malvern and the market town of Ledbury. The area benefits from good road and mainline rail links to the rest of the country. 2 BRIGHTON VILLAS • This period property has great potential either as an investment or to create a wonderful home. • This property previously had commercial use as a shop/office, this could potentially be reinstated for business use (subject to the necessary consents). • Retains original features including sash windows, an original fireplace and decorative quarry-tiled flooring in the entrance hallway. • The spacious, open-plan sitting/dining room features a working fireplace. • The property does require some modernisation but provides great opportunity. -

History 1890 – 1966

A HISTORY OF GLOUCESTER HARBOUR TRUSTEES By W. A. Stone Clerk to the Trustees 1958 -1966 PART 1 1890 - 1966 CONTENTS Chapter Page 1 Origin, Constitution and Membership, with details of Navigational Aids erected prior to the incorporation of the Gloucester Harbour Trustees on 5 July 1890 3 2 Navigational Aids 20 3 Finances 39 4 Spanning the Severn Estuary 51 5 New Works and other installation in the Severn Estuary 56 6 Stranding of Vessels and other Incidents 61 7 Northwick Moorings 71 8 Officers and Staff 74 1 FOREWORD In compiling this History I have endeavoured to give the reasons for the appointment of a body of Trustees to control a defined area of the Severn Estuary, and to tell of the great amount of work undertaken by the Trustees and the small staff in administering the requirements of the 1890 Act. It is probable that I have given emphasis to the erection and upkeep of the Navigational Aids, but it must be realised that this was the main requirement of the Act, to ensure that the Trustees, as a Harbour authority, disposed of their income in a manner which was calculated to benefit the navigation of the Severn Estuary. A great deal of research has been necessary and the advice and assistance given to me by the present Officers, and by others who held similar posts in the past, is greatly appreciated. Without their help the task would have been much more formidable. W A Stone Clerk to the Trustees December 1966 2 Chapter One ORIGIN, CONSTITUTION AND MEMBERSHIP WITH DETAILS OF NAVIGATIONAL AIDS ERECTED PRIOR TO THE INCORPORATION OF THE GLOUCESTER HARBOUR TRUSTEES ON 5 JULY 1890 To obtain the reasons for the constitution of a body of Trustees to control a defined area of the River Severn, it is necessary to go back to the year 1861. -

Weekly List of Planning Decisions Made 21 To

Weekly list of Decisions made from 21 - 25 September 2020 Direct access to search application page click here http://www.herefordshire.gov.uk/searchplanningapplications Parish Ward Ref no Planning code Valid date Site address Description Applicant name Applicant Applicant Decision Decision address Organisation Date Aston Ingham Penyard 201911 Planning 07/07/2020 Land at Glenleith Retaining an Mr & Mrs Glenleith Farm, Greenleaf 23/09/2020 Approved with Conditions Permission Farm, Gypsies Lane, existing cabin for Davies Kilcot, Newent, Architecture Kilcot, Newent, GL18 the purpose of Herefordshire, 1PG holiday let use. GL18 1PG Breinton Credenhill 202718 All others - Prior 19/08/2020 Wyevale Nurseries, Construction of a Mr Andrew Wyevale Agri 21/09/2020 Prior Approval Not Approval Wyevale Garden Winter fill irrigation Johnson Garden Centre Management Required Centre Offices, reservoir. Offices, Solutions Ltd Wyevale Way, Wyevale Way, Stretton Sugwas, Stretton Hereford, Sugwas, Herefordshire, HR4 Hereford, 7AY Herefordshire, HR4 7AY Bromyard and Bromyard West 201546 Planning 18/05/2020 Land adjacent to Hill Proposed portal Mr Justin Meadow Farm, Ian Savagar 22/09/2020 Approved with Conditions Winslow Permission Grove, Bredenbury, framed general Morgan Stoke Lacy, Bromyard, agricultural building Bromyard, Herefordshire Herefordshire, HR7 4HX Burghill Queenswood 201964 Works to trees 29/06/2020 8 Jasmine Lane, T1 Oak Reduce Mr Paul Leader 8 Jasmine Avalon Tree 23/09/2020 Trees covered by TPO – covered by TPO Burghill, Hereford, tree canopy -

ELECTORAL REVIEW of HEREFORDSHIRE

22 November 2012 Review Officer (Herefordshire) LGBCE, Layden House, 76-86 Turnmill Street, London EC1M 5LG Dear Sir ELECTORAL REVIEW of HEREFORDSHIRE I support the Commission’s plan for a 53 member council made up of single member wards, and hope the Commission will resist any moves to make way for any multi- member wards. There were some gremlins however in your report – most notably mis- reading of compass bearings! Eardisley is firmly located in the west, whereas Colwall is the east (page 15), and Fownhope is east of Hereford (page 17). But the Commission is to be congratulated on steering through a workable solution despite all the constraints imposed both by the regulations and the socio-political geography of Herefordshire. There does seem to be some problem with Holmer parish which has been included within adjacent areas of Hereford city without making this clear. This seems certain to meet with justified resistance from residents of Holmer parish. Otherwise I support the thrust of proposals for warding within Hereford city, as well as those for Ledbury and Leominster, and am content with the proposals for Ross on Wye. I support the bulk of the Commission’s proposals in rural areas but have some suggestions below which better match community links. First some suggestions for change of name of proposed rural wards LGBCE Nov 2012 comment preferred name Burghill long straggly ward from outskirts of Queenswood Leominster to Hereford Bishops Frome potential confusion with other communities Cradley within Frome valley which aren’t is this ward – prefer name of main parish in the ward Walford prefer current name which implies links Kerne Bridge across River Wye Ashperton Frome valley Clehonger name Madley as more central parish Madley & Clehonger Kimbolton Kimbolton & Brimfield Colwall The Commission has suggested that Mathon be added to Colwall but Colwall ward is already large enough and Mathon has stronger ties with Cradley so inclusion with Bishop’s Frome, renamed Cradley , would produce slightly more balanced electorates. -

GOING with the FLOW; How Colwall Stream Reaches the River by Rebecca Roseff

GOING WITH THE FLOW; How Colwall Stream Reaches The River by Rebecca Roseff Running along the edge of our garden in Colwall is a small stream, which though low in summer never actually runs dry. This is surprising as its source, a marshy area on the west side of the Malverns, is hardly half a mile away, you wouldn’t think there would be enough rain in that small amount of ground to keep it going throughout the year, but there is. I have always been intrigued by this stream because it takes what seems to me a contrary route. Rejecting the direction of all other streams in Herefordshire that go south, towards the Wye, this stream takes the opposite direction; north and into Worcestershire. To do this it has to make its way across the low lying area between Colwall and Mathon that geologists say had once been a glacial lake and then somehow find a gap through the steep hills around Suckley. Once past these its way is clear and it continues east along lower ground to the Teme five miles west of Worcester. I promised myself I would walk its whole distance one day, to see what fields and woods it passed, what mills it had powered and houses serviced along its 15 mile course to the end. So one fine May morning I set out with my walking companion, equipped with water and sandwiches, to follow its route. We left the house just after eight allowing ourselves a whole day to complete the task. I had calculated we could do it, there were footpaths all the way that followed, crossed and re-crossed our stream and, if we timed it right, we could catch the 417 bus back to Ledbury and from there the train home to Colwall. -

Minutes 26Th 02 2013

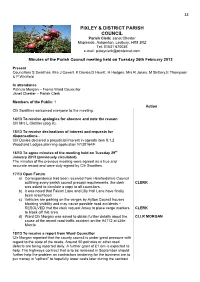

33 PIXLEY & DISTRICT PARISH COUNCIL Parish Clerk: Janet Chester Mapleside, Ashperton, Ledbury, HR8 2RZ Tel: 01531 670036 e-mail: [email protected] Minutes of the Parish Council meeting held on Tuesday 26th February 2013 Present Councillors S Swaithes, Mrs J Cowell, K Davies,D Hewitt, H Hodges, Mrs R Jones, M Skittery,E Thompson & P Whitfield In attendance Patricia Morgan – Frome Ward Councillor Janet Chester – Parish Clerk Members of the Public: 1 Action Cllr Swaithes welcomed everyone to the meeting. 14/13 To receive apologies for absence and note the reason Cllr Mrs L Clothier (dog ill), 15/13 To receive declarations of interest and requests for dispensations - Cllr Davies declared a prejudicial interest in agenda item 8.1.2 Woodland Lodges planning application N130164/F 16/13 To agree minutes of the meeting held on Tuesday 29th January 2013 (previously circulated) The minutes of the previous meeting were agreed as a true and accurate record and were duly signed by Cllr Swaithes. 17/13 Open Forum a) Correspondence had been received from Herefordshire Council outlining every parish council precept requirements, the clerk CLERK was asked to circulate a copy to all councilors. b) It was noted that Falcon Lane and Lilly Hall Lane have finally been resurfaced c) Vehicles are parking on the verges by Aylton Council houses blocking visibility and may cause possible road accidents – RESOLVED that the clerk request Amey to place verge markers CLERK to block off this area d) Ward Cllr Morgan was asked to obtain further details about the CLLR MORGAN cause of the recent road traffic accident on the A4172 at Little Marcle . -

Herefordshire News Sheet

CONTENTS ARS OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE FOR 1991 .................................................................... 2 PROGRAMME SEPTEMBER 1991 TO FEBRUARY 1992 ................................................... 3 EDITORIAL ........................................................................................................................... 3 MISCELLANY ....................................................................................................................... 4 BOOK REVIEW .................................................................................................................... 5 WORKERS EDUCATIONAL ASSOCIATION AND THE LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETIES OF HEREFORDSHIRE ............................................................................................................... 6 ANNUAL GARDEN PARTY .................................................................................................. 6 INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY MEETING, 15TH MAY, 1991 ................................................ 7 A FIELD SURVEY IN KIMBOLTON ...................................................................................... 7 FIND OF A QUERNSTONE AT CRASWALL ...................................................................... 10 BOLSTONE PARISH CHURCH .......................................................................................... 11 REDUNDANT CHURCHES IN THE DIOCESE OF HEREFORD ........................................ 13 THE MILLS OF LEDBURY ................................................................................................. -

Five Year Housing Land Supply Appendices July 2021

Five Year Housing Land Supply (2021 - 2026) Annual Position Statement at 1 April 2021 Appendices July 2021 hfdscouncil herefordshire.gov.uk Contents Page Number Appendix 1 – Commitments 2020 (all sites with Planning Permission 1 Bromyard Housing Market Area 1 Golden Valley Housing Market Area 3 Kington Housing Markey Area 5 Ledbury Housing Market Area 7 Leominster Housing Market Area 10 Hereford Housing Market Area 13 HD2 Sites 19 Ross on Wye Housing Market Area 20 Nursing Homes and Student Accommodation 26 Appendix 2a - Sites assessed for discounting 2020 27 Full Planning permission sites - Site assessment 27 and discounting of certain sites Full planning permission on small sites in the River Lugg 28 catchment - discounted sites Outline planning permission sites - Site assessment and 30 discounting of certain sites Resolution to grant Site assessment and discounting of 36 certain sites Appendix 2b - Agent Responses 2021 37 Appendix 3 - Neighbourhood Development Plans progress 2020 44 Appendix 4 – List of Completions 2020 62 Bromyard Housing Market Area 62 Golden Valley Housing Market Area 63 Kington Housing Markey Area 64 Ledbury Housing Market Area 65 Leominster Housing Market Area 66 Hereford Housing Market Area 67 HD2 Sites 69 Ross on Wye Housing Market Area 70 Appendix 5 - Annualised trajectory up to 2031 72 Appendix 6 - List of Parishes in the River Lugg Catchment Area 73 Appendix 7 - Map of Hereford city centre – Policy HD2 77 Not Under Comp in Lost Lost started con year through through General River HMA App no Address Parish 2020/21 -

Westbury, Cusop, Herefordshire. HR3

Westbury, Cusop, Herefordshire. HR3 5RF Description Hay-on-Wye is a delightful border market town, known as “the town of books” and Westbury is a spacious semi-detached offers an excellent range of services and house of brick construction within the facilities including dentists, doctors’ residential area of Cusop which is on the surgery, cinema, chemist, library, a outskirts of Hay-on-Wye on the wealth of second-hand bookshops and Herefordshire side of the England/Wales antique shops and an excellent and border. The house dates from about 1933 diverse market which operates every and offers generous accommodation over Thursday. There is a wide range of public two floors with the benefit of houses, restaurants and cafes, all located improvements in the form of new double- close to the town centre. Hay offers a glazed UPVC windows throughout, a re- primary school and there is a second fitted bathroom and a renewed rear primary school in the village of Clifford Westbury covered area. located only a few miles away. Hay-on- Cusop Wye is located on the eastern side of The Westbury stands in pleasant gardens with Brecon Beacons National Park, with an Nr Hay-on-Wye parking for several cars and ample room excellent tourist footfall throughout the Herefordshire for the construction of a garage (subject year and offers a wide range of leisure to planning). It also enjoys a fine HR3 5RF and recreational activities. southerly aspect with open views especially from the upper floors to the Brecon is found further afield mountains. approximately 16 miles away and Summary of features Hereford approximately 21 miles and the Situation • Charming semi-detached house latter also has a rail station with rail links The property enjoys a very pleasant to the rest of the country.