Mischief in Patagonia 7 H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fourth Quarter 2012 from the Editor As Many of You Have Heard, Travis

Fourth Quarter 2012 From the Editor As many of you have heard, Travis purchased a brand new boat. Not a good used boat, but a boat straight off the line. The boat, a Catalina 315, was christened "Kestrel" last month by one of the officers in the 60th Force Support Squadron. It replaces the much aged and badly damage 30 foot "Warrior". I have had the opportunity to sail her once. Because the boat is brand new, the Marina is going to be a bit more touchy about who sails her. Sailing "Kestrel" requires a checkout. Being checked out on "Warrior" does not qualify. "Kestrel" is very different. For Volunteer Skipper sails, normally two checked out crew members will be required. For the time being, classes will still be held on the old 27 foot boats. Students will then need to sail a few times with checked out skippers before advancing to getting checked out themselves. This is not a hazing program; this is designed to preserve a brand new asset. The biggest news this last quarter and the beginning of this one? The America's Cup. For two weeks, the medium size boats have been ripping across the waters of the bay. (I say "medium" because next year they will bring the "big" boats.) Some of our club members have participated by working the course. Some have been spectating from shore. Some of us have been watching from boats on the water. And some of use just watch it on television. No doubt these races are very different from America's Cup races in the past. -

March 16,1865

*Wima&mvciA~ Jit (ll I / < I ,s *'*iMt**Sf *««* ihnll ,-gaiatf^ a^bxjt ,DM.U —*“r ■*♦•- >’-*wA *i: aft _ “ ri A ■j"i?”s'"1 »iii*V ■«**■> tit * wrs»jt' i 4»Y>fw*-.»Sir^'> v,wi ".■i.,i:.!:L.^i.Y- ■' _ MahlMed June syear, in advance. "v^PMHiSSnKaacantt —n a- a.„n -,r i snow till at length I made my way into the ;>aTLAI3D Is AIL i KH3BB, * main igloo. Nukerton was not dead! She MISCELLANEOUS. MISCELLANEOUS. FOR BALE & TO LET. BUSINESS CARDS. BUSINESS CARlib. soiil, 1’. WiEMAIK. Editor, bieathed,and was much about the same as j merchandise. when I last saw her. I determined then to j ~=' .re puL'Ilehsa st He. 3XKSSXX.ay For Male. U IS SLl WP D « G2*EXCHANGE what I could for the CITY OF Dana & Co. H remain, doing dylug,— PORTLAND subscriber offers his fans* situated in Yar. i%ew & the 1865. Crop Sugar. Ti. A. FOSTER CO. The lamp was nearly out, cold was h»tcuee, PROSPECTUS FOR THEm u h, containing 45 ac es of good i&cd in- the thennometer outside being 51 degrees be- cluding abou' 6 a ires woodland. A two story Fish and SEWING l 8°I«i(l'8n«nUoag|U, and car, Sait, MAC FINES 150 the and I home, wood isg> huus >&. *»nd b »rn wit c-1 ,84 Rrxee Yellow now 1 AroR-rLABX>,>.iur low freezing point; though had on 0 Sugar, l.nding* fro:* FuK3eiapuiiiifiiiedat*s.ot B U NT IE S ! lar an ore an cf about 40 tree*, good Iruit Tl ere f.om M»l>iaaa. -

2010 Year Book

2010 YEAR BOOK www.massbaysailing.org $5.00 HILL & LOWDEN, INC. YACHT SALES & BROKERAGE J boat dealer for Massachusetts and southern new hampshire Hill & Lowden, Inc. offers the full range of new J Boat performance sailing yachts. We also have numerous pre-owned brokerage listings, including quality cruising sailboats, racing sailboats, and a variety of powerboats ranging from runabouts to luxury cabin cruisers. Whether you are a sailor or power boater, we will help you find the boat of your dreams and/or expedite the sale of your current vessel. We look forward to working with you. HILL & LOWDEN, INC. IS CONTINUOUSLY SEEKING PRE-OWNED YACHT LISTINGS. GIVE US A CALL SO WE CAN DISCUSS THE SALE OF YOUR BOAT www.Hilllowden.com 6 Cliff Street, Marblehead, MA 01945 Phone: 781-631-3313 Fax: 781-631-3533 Table of Contents ______________________________________________________________________ INFORMATION Letter to Skippers ……………………………………………………. 1 2009 Offshore Racing Schedule ……………………………………………………. 2 2009 Officers and Executive Committee …………… ……………............... 3 2009 Mass Bay Sailing Delegates …………………………………………………. 4 Event Sponsoring Organizations ………………………………………................... 5 2009 Season Championship ………………………………………………………. 6 2009 Pursuit race Championship ……………………………………………………. 7 Salem Bay PHRF Grand Slam Series …………………………………………….. 8 PHRF Marblehead Qualifiers ……………………………………………………….. 9 2009 J105 Mass Bay Championship Series ………………………………………… 10 PHRF EVENTS Constitution YC Wednesday Evening Races ……………………………………….. 11 BYC Wednesday Evening -

Update: America's

maxon motor Australia Pty Ltd Unit 1, 12 -14 Beaumont Rd. Mount Kuring -Gai NSW 2080 Tel. +61 2 9457 7477 [email protected] www.maxongroup.net.au October 02, 2019 The much -anticipated launch of the first two AC75 foiling monohull yachts from the Defender Emir- ates Team New Zealand and USA Challenger NYYC American Magic respectively did not disappoint the masses of America’s Cup fans waiting eagerly for their first gl impse of an AC75 ‘in the flesh’. Emirates Team New Zealand were the first to officially reveal their boat at an early morning naming cere- mony on September 6. Resplendent in the team’s familiar red, black and grey livery, the Kiwi AC75 was given the Maori nam e ‘Te Aihe’ (Dolphin). Meanwhile, the Americans somewhat broke with protocol by carrying out a series of un -announced test sails and were the first team to foil their AC75 on the water prior to a formal launch ceremony on Friday September 14 when their dark blue boat was given t he name ‘Defiant’. But it was not just the paint jobs that differentiated the first two boats of this 36th America’s Cup cycle – as it quickly became apparent that the New Zealand and American hull designs were also strikingly differ- ent.On first compar ison the two teams’ differing interpretations of the AC75 design rule are especially obvi- ous in the shape of the hull and the appendages. While the New Zealanders have opted for a bow section that is – for want of a better word – ‘pointy’, the Americans h ave gone a totally different route with a bulbous bow that some have described as ‘scow -like’ – although true scow bows are prohibited in the AC75 design rule. -

Unknown Lady Mise En Place Finishes 4Th in Section8 | Finishes 5Th in Cruising 3

AUGUST 2017 The monthly publication of Jackson Park Yacht Club This newsletter is interactive. Roll over for LINKS. Pam Rice, Editor May need to download for Interactivity. Unknown Lady Mise En Place Finishes 4th in Section8 | Finishes 5th in Cruising 3 ••••••••••••••••••• Congratulations to all of the crew who participated. Welcome home to Mischief and Witchcraft. jazzFest Gold Star Regatta Event — Smooth Sailing On Saturday, July 29, 2017, the Chicago Police Sailing Association in conjunc- tion with the Chicago Area Sail Association will hosted the first annual Gold Star Regatta at the Jackson Park Yacht Club. In addition to a competitive dis- tance regatta (which was cancelled due to small craft warnings), the event in- Would you like to enjoy a cluded a family friendly post-race party with beverages, local food trucks, the beautiful evening sitting mounted police, Chicago Fire Department, Chicago Police Department, the outside at the Jackson Park CPD Marine Division, the US Coast Guard, entertainment and much more. Activities throughout the day will benefit families of first responders who have Yacht Club? fallen in the line of duty or have been catastrophically injured. Come experience Harvey started the Chicago Police Sailing Association in March 2016 in the hope of encouraging more law enforcement officials to take up the pastime. the sounds of He’s hoping to further this cause with the Gold Star Regatta. Proceeds from the regatta are slated for police charities, including the Yvonne Stroud Brotherhood for the Fallen, the Chicago Police Memorial Foundation and the 100 Club of Chicago. for our annual Jazz Fest Saturday April 12th @ 6:00 p.m. -

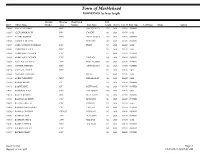

Active Waitlist Main Alphabetical

Town of Marblehead MOORINGS by boat length Mooring Mooring Registration Boat Bill # Owner Name Number Area Number Boat Name Length Res Ty Cove M Boat Type Cell Phone Phone Address 104948 AINLAY STEPHEN BYC TRANQUILITY 026 2020 MAIN POWER 103837 ALEXANDER JOHN BYC URGENT 033 2020 MAIN SAIL 103830 ALPERT ROBERT BYC SWIFT CLOUD 030 2020 MAIN POWER 104543 AMBERIK MELISSA PRELUDE 020 2020 MAIN POWER 102968 AMES- LAWSON DANIELLE EYC FLIRT 034 2020 MAIN SAIL 105636 ANDERSON CARLY BYC 028 2020 MAIN SAIL 104302 ANDREASEN PATRICK EYC 017 2020 MAIN POWER 104803 ANDREASEN PATRICK EYC VINTAGE 036 2020 MAIN POWER 105288 ANNUNZIATA SCOTT ANY REEL PATRIOT 030 2020 MAIN POWER 105103 ARTHUR STEPHEN BYC ANCHORMAN 026 2020 MAIN POWER 104254 ASPINALL JENNIE BYC 033 2020 MAIN SAIL 105828 ASPINALL JENNIFER DAISY 017 2020 MAIN SAIL 103408 AUBIN CHRISTINE MYC BREAKAWAY 040 2020 MAIN SAIL 105030 BABINE BRYCE LIT 015 2020 MAIN POWER 104676 BABINE PETE LIT BETTI ROSE 022 2020 MAIN POWER 104022 BACKMAN ELKE EYC SARABAND 036 2020 MAIN SAIL 104674 BAILEY DAMIEN DYC BLUE STEEL 023 2020 MAIN POWER 104163 BALUNAS ANDREW CYC MOHAWK 021 2020 MAIN POWER 104498 BALUNAS DYLAN CYC PATRICK 013 2020 MAIN power 105165 BARBER JOHN FORBES CYC CANTAB 032 2020 MAIN POWER 105740 BARNES GREGORY COM ST LOW-KEY 023 2020 MAIN POWER 103845 BARRETT JACK ANY SLAP SHOT 017 2020 MAIN POWER 104846 BARRETT STEVE ANY RELAPSE 033 2020 MAIN SAIL 104315 BARRY STEPHEN BYC SEA STAR 023 2020 MAIN POWER 105998 BECKER GENEVA EYC 024 2020 MAIN POWER 105997 BECKER GRADY EYC 024 2020 MAIN POWER User: TerryT -

Seacare Authority Exemption

EXEMPTION 1—SCHEDULE 1 Official IMO Year of Ship Name Length Type Number Number Completion 1 GIANT LEAP 861091 13.30 2013 Yacht 1209 856291 35.11 1996 Barge 2 DREAM 860926 11.97 2007 Catamaran 2 ITCHY FEET 862427 12.58 2019 Catamaran 2 LITTLE MISSES 862893 11.55 2000 857725 30.75 1988 Passenger vessel 2001 852712 8702783 30.45 1986 Ferry 2ABREAST 859329 10.00 1990 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht 2GETHER II 859399 13.10 2008 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht 2-KAN 853537 16.10 1989 Launch 2ND HOME 856480 10.90 1996 Launch 2XS 859949 14.25 2002 Catamaran 34 SOUTH 857212 24.33 2002 Fishing 35 TONNER 861075 9714135 32.50 2014 Barge 38 SOUTH 861432 11.55 1999 Catamaran 55 NORD 860974 14.24 1990 Pleasure craft 79 199188 9.54 1935 Yacht 82 YACHT 860131 26.00 2004 Motor Yacht 83 862656 52.50 1999 Work Boat 84 862655 52.50 2000 Work Boat A BIT OF ATTITUDE 859982 16.20 2010 Yacht A COCONUT 862582 13.10 1988 Yacht A L ROBB 859526 23.95 2010 Ferry A MORNING SONG 862292 13.09 2003 Pleasure craft A P RECOVERY 857439 51.50 1977 Crane/derrick barge A QUOLL 856542 11.00 1998 Yacht A ROOM WITH A VIEW 855032 16.02 1994 Pleasure A SOJOURN 861968 15.32 2008 Pleasure craft A VOS SANTE 858856 13.00 2003 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht A Y BALAMARA 343939 9.91 1969 Yacht A.L.S.T. JAMAEKA PEARL 854831 15.24 1972 Yacht A.M.S. 1808 862294 54.86 2018 Barge A.M.S. -

The Indian Ocean Crossing Compendium, Also Available At

The Red Sea Route Compendium A Compilation of Guidebook References and Cruising Reports Covering the route from Cochin, India up through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal IMPORTANT: USE ALL INFORMATION IN THIS DOCUMENT AT YOUR OWN RISK!! Rev 2020.2 – 03 August 2020 We welcome updates to this guide! (especially for places we have no cruiser information on) Email Soggy Paws at sherry –at- svsoggypaws –dot- com. You can also contact us on Sailmail at WDI5677 The current home of the official copy of this document is http://svsoggypaws.com/files/ If you found it posted elsewhere, there might be an updated copy at svsoggypaws.com. Page 1 Revision Log Many thanks to all who have contributed over the years!! Rev Date Notes 2020.0 08-Feb-2020 Initial version, still very rough at this point!! Updates from cruisers stopping in Uligan, Maldives. Update on quarantine in Cochin. Update from Joanna on Djibouti. 2020.1 10-May-2020 Update from Bird of Passage on Socotra. Updates on possible Winlink stations for weather. 2020.2 03-Aug-2020 s/v Joana’s recap of the trip from SE Asia to Med Page 2 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 ORGANIZATION OF THE GUIDE .......................................................................................................... 6 1.2 OVERVIEW OF THE AREA .................................................................................................................. 7 1.3 TIME ZONES ................................................................................................................................. -

Volunteer Manual

Gundalow Company Volunteer Manual Updated Jan 2018 Protecting the Piscataqua Region’s Maritime Heritage and Environment through Education and Action Table of Contents Welcome Organizational Overview General Orientation The Role of Volunteers Volunteer Expectations Operations on the Gundalow Workplace Safety Youth Programs Appendix Welcome aboard! On a rainy day in June, 1982, the replica gundalow CAPTAIN EDWARD H. ADAMS was launched into the Piscataqua River while several hundred people lined the banks to watch this historic event. It took an impressive community effort to build the 70' replica on the grounds of Strawbery Banke Museum, with a group of dedicated shipwrights and volunteers led by local legendary boat builder Bud McIntosh. This event celebrated the hundreds of cargo-carrying gundalows built in the Piscataqua Region starting in 1650. At the same time, it celebrated the 20th-century creation of a unique teaching platform that travelled to Piscataqua region riverfront towns carrying a message that raised awareness of this region's maritime heritage and the environmental threats to our rivers. For just over 25 years, the ADAMS was used as a dock-side attraction so people could learn about the role of gundalows in this region’s economic development as well as hundreds of years of human impact on the estuary. When the Gundalow Company inherited the ADAMS from Strawbery Banke Museum in 2002, the opportunity to build a new gundalow that could sail with students and the public became a priority, and for the next decade, we continued the programs ion the ADAMS while pursuing the vision to build a gundalow that could be more than a dock-side attraction. -

Dictionary.Pdf

THE SEAFARER’S WORD A Maritime Dictionary A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Ranger Hope © 2007- All rights reserved A ● ▬ A: Code flag; Diver below, keep well clear at slow speed. Aa.: Always afloat. Aaaa.: Always accessible - always afloat. A flag + three Code flags; Azimuth or bearing. numerals: Aback: When a wind hits the front of the sails forcing the vessel astern. Abaft: Toward the stern. Abaft of the beam: Bearings over the beam to the stern, the ships after sections. Abandon: To jettison cargo. Abandon ship: To forsake a vessel in favour of the life rafts, life boats. Abate: Diminish, stop. Able bodied seaman: Certificated and experienced seaman, called an AB. Abeam: On the side of the vessel, amidships or at right angles. Aboard: Within or on the vessel. About, go: To manoeuvre to the opposite sailing tack. Above board: Genuine. Able bodied seaman: Advanced deckhand ranked above ordinary seaman. Abreast: Alongside. Side by side Abrid: A plate reinforcing the top of a drilled hole that accepts a pintle. Abrolhos: A violent wind blowing off the South East Brazilian coast between May and August. A.B.S.: American Bureau of Shipping classification society. Able bodied seaman Absorption: The dissipation of energy in the medium through which the energy passes, which is one cause of radio wave attenuation. Abt.: About Abyss: A deep chasm. Abyssal, abysmal: The greatest depth of the ocean Abyssal gap: A narrow break in a sea floor rise or between two abyssal plains. -

February 06,1863

PORTLAND DAILY PRESS.# mm———^——— ^^ MHMHiM^M^_ VOL. 1. FRIDAY PORTLAND, ME., MORNING, FEBRUARY 6, 1863. NO. 194. ~~ PORTLAND DAILY PRESS _STEAMBOATS. INSURANCE. PRINTING. BUSINESS CARDS. BUSINESS CARDS. Is published at No. 82} EXCHANGE STREET, | medical! Portlnnd York in FOX BLOCK, by and \cw Kiramrn. JOHN E. THE PORTLAND DAILY PRE88 DOW, Removal ! JOHN T. ROGERS Ac H N. A. A CO. SEMIWEMLY LINE. CO., H. H A Y, FOSTER Marine, Fire & Life Insurance Agency. The splendid and fast Steamships The undoreigned hue removed hie Office to General %* Term s : “CHESAPEAKE,” ('apt. Willett, STEAM POWER ^ and “PARKERSBURG,” Captain Liverpool and London Fire and Life In- Ho. 166 Fore head of Tr* Portland Daily Press is published every Huffman, will, until farther notice, St., Long Wharf, COMMISSION MERCHANTS. at run as follows: surance Co. morning, (Sundays excepted), 96,00 per year is ad- Where ho ie to write AND Leave Browns Wharf, Portland, WEDNES- prepared any amount of WHOLESALE DEALERS IN to which will be added oents for every CAPITAL AND SURPLUS vance, twenty-five DAY, and SATURDAY, at 4 P. M., and leave Pier OVER »10,000,000. each three months’ delay, and If not paid at the end 9 North River. New York, WEDNESDAY Book and Job marine. Fire and Life Insurance, Flour, Provisions and Produce every Tori 11 ovd Viva Tnanvnn am /1a nf ik. fl I of the year the paper will be discontinued. and SATURDAY, at 3 o’clock. P. M. Printing Office, These vessels are fitted with fine accommodations that may be wanted. Single copies three cents. -

October 13, 1983 Oste (W,G-6Axl,Fl)7A Battles at Schoolcraft Gym Vs

Volume 19 Number 32 Thursday. Ootober 13.1983 * Westland, Michigan Twenty-five cents Ji-v&'> :'-r- :::mm.mm§. io^gjafc^rj^-^fetr^i^.al^^Ti^.ik Ml: ^ii^ilMiilllS ••, v.- .:-i :-, i c-..-... -V • '». : ( • lyt:.-.-. v:| Ki,-1:. ki .• r. Candidates call for development at chamber lunch By 8andrs Armbru«tsr Asked If such Illegal transfers were editor made while he was finance director, Herbert said, "Absolutely not. Three Gearing remarks to the concerns of years ago the city had a $1 million sur their business audience, six of v eight plus, There wasn't the need. Why would candidates running for city council ad anyone do that with a surplus?" dressed Issues concerning Westland's economic development during speeches QUESTIONING Herbert about the before the chamber of commerce. surplus, Elizabeth Davis, Pickering's But it was Mayor Charles Pickering secretary, asked why there was a defi who fired the opening salvo during the cit when the mayor took office. • question and answer period by charg "There was $1.7 million In the banks ing that the "incumbents are running and on deposit when I walked out the their campaign based on my record, door," said Pickering. not theirs." . He admitted, however, that his de Pickering asked Councilman Kent partment had predicted a $300,000 def Herbert, whose appointment the mayor icit by June that year and had submit had vetoed, if he would accept blame ted a plan on how it should be handled. for "bad deals" made while Herbert "Unfortunately, nothing was done," was the city's finance director.