Typeface Features and Legibility Research T Charles Bigelow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supreme Court of the State of New York Appellate Division: Second Judicial Department

Supreme Court of the State of New York Appellate Division: Second Judicial Department A GLOSSARY OF TERMS FOR FORMATTING COMPUTER-GENERATED BRIEFS, WITH EXAMPLES The rules concerning the formatting of briefs are contained in CPLR 5529 and in § 1250.8 of the Practice Rules of the Appellate Division. Those rules cover technical matters and therefore use certain technical terms which may be unfamiliar to attorneys and litigants. The following glossary is offered as an aid to the understanding of the rules. Typeface: A typeface is a complete set of characters of a particular and consistent design for the composition of text, and is also called a font. Typefaces often come in sets which usually include a bold and an italic version in addition to the basic design. Proportionally Spaced Typeface: Proportionally spaced type is designed so that the amount of horizontal space each letter occupies on a line of text is proportional to the design of each letter, the letter i, for example, being narrower than the letter w. More text of the same type size fits on a horizontal line of proportionally spaced type than a horizontal line of the same length of monospaced type. This sentence is set in Times New Roman, which is a proportionally spaced typeface. Monospaced Typeface: In a monospaced typeface, each letter occupies the same amount of space on a horizontal line of text. This sentence is set in Courier, which is a monospaced typeface. Point Size: A point is a unit of measurement used by printers equal to approximately 1/72 of an inch. -

Cloud Fonts in Microsoft Office

APRIL 2019 Guide to Cloud Fonts in Microsoft® Office 365® Cloud fonts are available to Office 365 subscribers on all platforms and devices. Documents that use cloud fonts will render correctly in Office 2019. Embed cloud fonts for use with older versions of Office. Reference article from Microsoft: Cloud fonts in Office DESIGN TO PRESENT Terberg Design, LLC Index MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS A B C D E Legend: Good choice for theme body fonts F G H I J Okay choice for theme body fonts Includes serif typefaces, K L M N O non-lining figures, and those missing italic and/or bold styles P R S T U Present with most older versions of Office, embedding not required V W Symbol fonts Language-specific fonts MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS Abadi NEW ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Abadi Extra Light ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Note: No italic or bold styles provided. Agency FB MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Agency FB Bold ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Note: No italic style provided Algerian MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 01234567890 Note: Uppercase only. No other styles provided. Arial MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Italic ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Bold ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Bold Italic ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ -

Typography One Typeface Classification Why Classify?

Typography One typeface classification Why classify? Classification helps us describe and navigate type choices Typeface classification helps to: 1. sort type (scholars, historians, type manufacturers), 2. reference type (educators, students, designers, scholars) Approximately 250,000 digital typefaces are available today— Even with excellent search engines, a common system of description is a big help! classification systems Many systems have been proposed Francis Thibaudeau, 1921 Maximillian Vox, 1952 Vox-ATypI, 1962 Aldo Novarese, 1964 Alexander Lawson, 1966 Blackletter Venetian French Dutch-English Transitional Modern Sans Serif Square Serif Script-Cursive Decorative J. Ben Lieberman, 1967 Marcel Janco, 1978 Ellen Lupton, 2004 The classification system you will learn is a combination of Lawson’s and Lupton’s systems Black Letter Old Style serif Transitional serif Modern Style serif Script Cursive Slab Serif Geometric Sans Grotesque Sans Humanist Sans Display & Decorative basic characteristics + stress + serifs (or lack thereof) + shape stress: where the thinnest parts of a letter fall diagonal stress vertical stress no stress horizontal stress Old Style serif Transitional serif or Slab Serif or or reverse stress (Centaur) Modern Style serif Sans Serif Display & Decorative (Baskerville) (Helvetica) (Edmunds) serif types bracketed serifs unbracketed serifs slab serifs no serif Old Style Serif and Modern Style Serif Slab Serif or Square Serif Sans Serif Transitional Serif (Bodoni) or Egyptian (Helvetica) (Baskerville) (Rockwell/Clarendon) shape Geometric Sans Serif Grotesk Sans Serif Humanist Sans Serif (Futura) (Helvetica) (Gill Sans) Geometric sans are based on basic Grotesk sans look precisely drawn. Humanist sans are based on shapes like circles, triangles, and They have have uniform, human writing. -

Letters Are Made for Reading

Letters are made for reading A lot of things has to be taken into consideration when you make typographical choices. With the typography of logos and headlines, etc, the style and tone of your publication is determined. But when it comes to the body text, legibility is more important than anything else. BACK IN THE LATE SEVENTIES when I was study- In ”micro” typography, on the other hand, legi- ing architecture at the Royal Academy of Arts, one bility is more important than style. Or maybe we of the rules we were taught was: ”A building must ought to talk about ”readability”, a phrase used by have a distinctive entrance”. That ought to make some typographers, making the point that what sense: It hardly matters what’s inside a house if you fi nd legible depends more than anything else you can’t fi nd the door, does it? on what you are used to read. However perfect Good typography, I’d say, is like the entrance the letterforms of a new typeface, it may still ap- to a house. It should lead you inside, help you to pear hard to read if people think it looks strange. the contents—which is indeed the most important Perhaps this is why most people still prefer text thing. with serifs even though repeated surveys have But then again, what is good typography? Well, shown no legibility differences between sans and as there are numerous disciplines of graphic de- serif typefaces. sign, this question does not have one single—or If you read the same newspaper every day, simple—answer. -

15 the Effect of Font Type on Screen Readability by People with Dyslexia

The Effect of Font Type on Screen Readability by People with Dyslexia LUZ RELLO and RICARDO BAEZA-YATES, Web Research Group, DTIC, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain Around 10% of the people have dyslexia, a neurological disability that impairs a person’s ability to read and write. There is evidence that the presentation of the text has a significant effect on a text’s accessibility for people with dyslexia. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no experiments that objectively 15 measure the impact of the typeface (font) on screen reading performance. In this article, we present the first experiment that uses eye-tracking to measure the effect of typeface on reading speed. Using a mixed between-within subject design, 97 subjects (48 with dyslexia) read 12 texts with 12 different fonts. Font types have an impact on readability for people with and without dyslexia. For the tested fonts, sans serif , monospaced, and roman font styles significantly improved the reading performance over serif , proportional, and italic fonts. On the basis of our results, we recommend a set of more accessible fonts for people with and without dyslexia. Categories and Subject Descriptors: H.5.2 [Information Interfaces and Presentation]: User Interfaces— Screen design, style guides; K.4.2 [Computers and Society]: Social Issues—Assistive technologies for per- sons with disabilities General Terms: Design, Experimentation, Human Factors Additional Key Words and Phrases: Dyslexia, learning disability, best practices, web accessibility, typeface, font, readability, legibility, eye-tracking ACM Reference Format: Luz Rello and Ricardo Baeza-Yates. 2016. The effect of font type on screen readability by people with Dyslexia. -

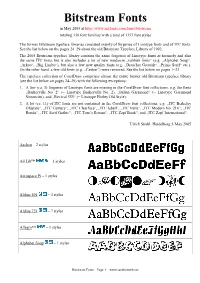

Bitstream Fonts in May 2005 at Totaling 350 Font Families with a Total of 1357 Font Styles

Bitstream Fonts in May 2005 at http://www.myfonts.com/fonts/bitstream totaling 350 font families with a total of 1357 font styles The former Bitstream typeface libraries consisted mainly of forgeries of Linotype fonts and of ITC fonts. See the list below on the pages 24–29 about the old Bitstream Typeface Library of 1992. The 2005 Bitstream typeface library contains the same forgeries of Linotype fonts as formerly and also the same ITC fonts, but it also includes a lot of new mediocre „rubbish fonts“ (e.g. „Alphabet Soup“, „Arkeo“, „Big Limbo“), but also a few new quality fonts (e.g. „Drescher Grotesk“, „Prima Serif“ etc.). On the other hand, a few old fonts (e.g. „Caxton“) were removed. See the list below on pages 1–23. The typeface collection of CorelDraw comprises almost the entire former old Bitstream typeface library (see the list below on pages 24–29) with the following exceptions: 1. A few (ca. 3) forgeries of Linotype fonts are missing in the CorelDraw font collections, e.g. the fonts „Baskerville No. 2“ (= Linotype Baskerville No. 2), „Italian Garamond“ (= Linotype Garamond Simoncini), and „Revival 555“ (= Linotype Horley Old Style). 2. A lot (ca. 11) of ITC fonts are not contained in the CorelDraw font collections, e.g. „ITC Berkeley Oldstyle“, „ITC Century“, „ITC Clearface“, „ITC Isbell“, „ITC Italia“, „ITC Modern No. 216“, „ITC Ronda“, „ITC Serif Gothic“, „ITC Tom’s Roman“, „ITC Zapf Book“, and „ITC Zapf International“. Ulrich Stiehl, Heidelberg 3-May 2005 Aachen – 2 styles Ad Lib™ – 1 styles Aerospace Pi – 1 styles Aldine -

Afgbaskerville (The Type Face)

gfaBaskerville (the type face) xagfi {the type} {the man} abcdefghijklmn opqrstuvwxyz ABCDEFGHI JKLMNOPQR STUVWXYZ Having been an early admirer of the beauty of letters, I vertical stress relatively low contrast “became insensibly desirous of contributing to the perfection Baskerville is a transitional type of them. I formed to myself ideas of greater accuracy than had yet appeared, and had endeavoured to produce a set of types according to what I conceived to be their true { old style type modern type proportion. oblique stress vertical stress —John Baskerville, preface to Milton, 1758 relatively low contrast high contrast (Anatomy of a Typeface) ” {looks} use of orthogonal lines use of orthogonal + curvy lines FHTt BDp use of curvy lines use of diagonal lines cOQ vwXZ In order to truely appreciate the quialities of Baskerville, one must understand the The Baskerville type is known for the crisp edges, high contrast and generous process of its creation. Being a printer, John Baskerville paid close attention to the proportions. Baskerville is categorized as a transitional typeface in between classical technology, creating his own intense black ink. He boiled fine linseed oil to a certain typefaces and the high contrast modern faces. density, dissolved rosin, and let it subside for months before using it. He also studied and invested in presses, resulting in the development of high standards for presses altogether. {anatomy} crossbar serif ear head serif ascender counter apex A a x g Q b q O spur x-height descender swash {characteristics} {1}g Q {2} A {3} {4}J {5}C {6}E {7}ea {1} tail on lower case g does not close {2} swash-like tail of Q {4} J well below baseline {3} high crossbar and pointed apex of A {5} top and bottom serifs on C {6} long lower arm of E {7} small counter of italic e compared to italic a {comparison} Bembo Baskerville Bembo Baskerville d The head serif of Baskerville is generally more horizontal than that of Bembo. -

Basic Styles of Lettering for Monuments and Markers.Indd

BASIC STYLES OF LETTERING FOR MONUMENTS AND MARKERS Monument Builders of North America, Inc. AA GuideGuide ToTo TheThe SelectionSelection ofof LETTERINGLETTERING From primitive times, man has sought to crude or garish or awkward letters, but in communicate with his fellow men through letters of harmonized alphabets which have symbols and graphics which conveyed dignity, balance and legibility. At the same meaning. Slowly he evolved signs and time, they are letters which are designed to hieroglyphics which became the visual engrave or incise cleanly and clearly into expression of his language. monumental stone, and to resist change or obliteration through year after year of Ultimately, this process evolved into the exposure. writing and the alphabets of the various tongues and civilizations. The early scribes The purpose of this book is to illustrate the and artists refi ned these alphabets, and the basic styles or types of alphabets which have development of printing led to the design been proved in memorial art, and which are of alphabets of related character and ready both appropriate and practical in the lettering readability. of monuments and markers. Memorial art--one of the oldest of the arts- Lettering or engraving of family memorials -was among the fi rst to use symbols and or individual markers is done today with “letters” to inscribe lasting records and history superb fi delity through the use of lasers or the into stone. The sculptors and carvers of each sandblast process, which employs a powerful generation infl uenced the form of letters and stream or jet of abrasive “sand” to cut into the numerals and used them to add both meaning granite or marble. -

CSS Font Stacks by Classification

CSS font stacks by classification Written by Frode Helland When Johann Gutenberg printed his famous Bible more than 600 years ago, the only typeface available was his own. Since the invention of moveable lead type, throughout most of the 20th century graphic designers and printers have been limited to one – or perhaps only a handful of typefaces – due to costs and availability. Since the birth of desktop publishing and the introduction of the worlds firstWYSIWYG layout program, MacPublisher (1985), the number of typefaces available – literary at our fingertips – has grown exponen- tially. Still, well into the 21st century, web designers find them selves limited to only a handful. Web browsers depend on the users own font files to display text, and since most people don’t have any reason to purchase a typeface, we’re stuck with a selected few. This issue force web designers to rethink their approach: letting go of control, letting the end user resize, restyle, and as the dynamic web evolves, rewrite and perhaps also one day rearrange text and data. As a graphic designer usually working with static printed items, CSS font stacks is very unfamiliar: A list of typefaces were one take over were the previous failed, in- stead of that single specified Stempel Garamond 9/12 pt. that reads so well on matte stock. Am I fighting the evolution? I don’t think so. Some design principles are universal, independent of me- dium. I believe good typography is one of them. The technology that will let us use typefaces online the same way we use them in print is on it’s way, although moving at slow speed. -

Presentation

Born Broken: Fonts And Information Loss In Legacy Documents Geoffrey Brown and Kam Woods Indiana University School of Informatics and Computing Key Questions How pervasive are font substitution problems ? What information is available to identify fonts ? How well can we match the fonts required by a document collection ? How can we assist archivists in identifying serious font issues ? Page 8 MCTM Bulletin February 2005 K: I knew what you meant. I was just kidding. I’ll do XüLLbl (W):InputQ:FnOff :"""Y =! Y",Y#:PlotsOff the dishes tonight at dinner. YüL‚(W):Goto:0!Xscl:0!Yscl:Plot1(Scatt T er,L#,L$,&) PlotsOn 1:ZoomStat:StorePic Pic1 Lbl Q:FnOff :""üY :PlotsOff Jennifer felt better so offered the following challenge to Pause :Goto T Kevin. Lbl:0üXscl:0üYscl:Plot1(Scatt S:ClrHome:2!dim(L%er,L):dim(L ,L‚,Ñ)# )!N J: What type of general statement can you make DispPlotsOn "NO. 1:ZoomStat:StorePic OF Pic1 regarding the various polygons and, better yet, what PausePTS.":Output(1,13,N):Pause :Goto T can you say about a figure that looks like this? LblFor(I,1,N):ClrHome S:ClrHome:2üdim(Lƒ):dim(L )üN Disp "NO. "PT. OF NO.","":Output(1,9,I) PTS.":Output(1,13,N):Pause L#(I)!L%(1):L$(I)!L%(2) For(I,1,N):ClrHome Disp L%:Pause :End:Goto T LblDisp "PT.0:Menu(" NO.","":Output(1,9,I) MODELS R""," LINEAR (2)",1,"L(I)üLƒ(1):L‚(I)üLƒ(2) QUADRATIC",2," CUBIC/QUARTIC",3,"Disp Lƒ:Pause :End:Goto LOGARITHMIC",4," T LblEXPONENTIAL",5," 0:Menu(" MODELS POWER",6," RÜ"," LINEAR MAIN (2)",1," MENU",T) QUADRATIC",2," CUBIC/QUARTIC",3," Lbl 1:"aX+b"!Y# Kevin was impressed. -

Steganography in Arabic Text Using Full Diacritics Text

Steganography in Arabic Text Using Full Diacritics Text Ammar Odeh Khaled Elleithy Computer Science & Engineering, Computer Science & Engineering, University of Bridgeport, University of Bridgeport, Bridgeport, CT06604, USA Bridgeport, CT06604, USA [email protected] [email protected] Abstract 1. Substitution: Exchange some small part of the carrier file The need for secure communications has significantly by hidden message. Where middle attacker can't observe the increased with the explosive growth of the internet and changes in the carrier file. On the other hand, choosing mobile communications. The usage of text documents has replacement process it is very important to avoid any doubled several times over the past years especially with suspicion. This means to select insignificant part from the mobile devices. In this paper we propose a new file then replace it. For instance, if a carrier file is an image Steganogaphy algorithm for Arabic text. The algorithm (RGB) then the least significant bit (LSB) will be used as employs some Arabic language characteristics, which exchange bit [4]. represent as small vowel letters. Arabic Diacritics is an 2. Injection: By adding hidden data into the carrier file, optional property for any text and usually is not popularly where the file size will increase and this will increase the used. Many algorithms tried to employ this property to hide probability being discovered. The main goal in this data in Arabic text. In our method, we use this property to approach is how to present techniques to add hidden data hide data and reduce the probability of suspicions hiding. and to void attacker suspicion [4]. -

CLASS: Working with Students with Dysgraphia

A Quick Guide to Working with Students with Dysgraphia Characteristics of the Condition This is a general term is used to describe any of several distinct difficulties in producing written language. These problems may be developmental in origin or may result from a brain injury or neurological disease. They often occur with other difficulties (e.g., dyslexia), but may be encountered in isolation. • Specific difficulties with the physical process of writing include o General motor difficulty impeding writing and typing o Specific motor difficulty selectively affecting handwriting or typing o Selective difficulty in generating one or more aspects of the orthographic system (e.g., print vs. cursive forms; upper case vs. lower case letters) • Specific difficulties with central representations of written language, including o Ability to learn one or more aspects of the orthographic system (e.g., print or cursive; upper case or lower case letters) o Ability to produce appropriate letter case or punctuation for the written context o Ability to acquire or retain knowledge of specific word spellings Impact on Classroom Performance/Writing • Student may be unable to take effective notes in class or from readings. • Writing by hand may be slow and effortful, resulting in diminished content in papers and essays in comparison with the student’s knowledge. • Legibility of written work may be poor, becoming increasingly worse from the beginning to the end of the document. • Capitalization and punctuation errors inconsistent with student’s linguistic skills may be seen. • Spelling may be inaccurate and/or inconsistent. • Vocabulary used in writing may be significantly restricted in comparison to the student’s reading or spoken vocabulary (may be due to concerns about spelling accuracy).