STATUS EPILEPTICUS in CANINE PATIENTS Oriana D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midazolam Injection, USP

Midazolam Injection, USP 2 mg per 2 mL | NDC 70860-600-02 50 mg per 10 mL | NDC 70860-601-10 ATHENEX AccuraSEETM PACKAGING AND LABELING BIG, BOLD AND BRIGHT — TO HELP YOU SEE IT, SAY IT AND PICK IT RIGHT DIFFERENTIATION IN EVERY LABEL, DESIGNED TO HELP REDUCE MEDICATION ERRORS PLEASE SEE FULL PRESCRIBING INFORMATION, INCLUDING BOXED WARNING, FOR MIDAZOLAM INJECTION, USP, ENCLOSED. THE NEXT GENERATION OF PHARMACY INNOVATION To order, call 1-855-273-0154 or visit www.Athenexpharma.com Midazolam Injection, USP 2 5 mg NDC 70860-600-02 0 NDC 70860-601-10 2 mg per 2 mL mg 50 mg per 10 mL DESCRIPTION Glass Vial DESCRIPTION Glass Vial CONCENTRATION 1 mg per mL CONCENTRATION 5 mg per mL CLOSURE 13 mm CLOSURE 20 mm UNIT OF SALE 25 vials UNIT OF SALE 10 vials BAR CODED Yes BAR CODED Yes STORAGE Room Temp. STORAGE Room Temp. • AP RATED • PRESERVATIVE-FREE • AP RATED • NOT MADE WITH NATURAL RUBBER LATEX • NOT MADE WITH NATURAL RUBBER LATEX CHOOSE AccuraSEETM FOR YOUR PHARMACY Our proprietary, differentiated and highly-visible label designs can assist pharmacists in accurate medication selection. With a unique label design for every Athenex product, we’re offering your pharmacy added AccuraSEE. The idea is simple: “So what you see is exactly what you get.” Athenex, AccuraSEE and all label designs are copyright of Athenex. ©2020 Athenex. 000527 To order, call 1-855-273-0154 or visit www.Athenexpharma.com • Midazolam hydrochloride mufti-dose vial, is not intended for intrathecal or epidural • Anesthetic and sedation drugs are a necessary part of the care of children needing Midazolam Injection, USP administration, and is contraindicated for use in premature infants, because the formulation surgery, other procedures, or tests that cannot be delayed, and no specific medications INDICATIONS AND USAGE contains benzyl alcohol as a preservative. -

The Emergence of New Psychoactive Substance (NPS) Benzodiazepines

Issue: Ir Med J; Vol 112; No. 7; P970 The Emergence of New Psychoactive Substance (NPS) Benzodiazepines. A Survey of their Prevalence in Opioid Substitution Patients using LC-MS S. Mc Namara, S. Stokes, J. Nolan HSE National Drug Treatment Centre Abstract Benzodiazepines have a wide range of clinical uses being among the most commonly prescribed medicines globally. The EU Early Warning System on new psychoactive substances (NPS) has over recent years detected new illicit benzodiazepines in Europe’s drug market1. Additional reference standards were obtained and a multi-residue LC- MS method was developed to test for 31 benzodiazepines or metabolites in urine including some new benzodiazepines which have been classified as New Psychoactive Substances (NPS) which comprise a range of substances, including synthetic cannabinoids, opioids, cathinones and benzodiazepines not covered by international drug controls. 200 urine samples from patients attending the HSE National Drug Treatment Centre (NDTC) who are monitored on a regular basis for drug and alcohol use and which tested positive for benzodiazepine class drugs by immunoassay screening were subjected to confirmatory analysis to determine what Benzodiazepine drugs were present and to see if etizolam or other new benzodiazepines are being used in the addiction population currently. Benzodiazepine prescription and use is common in the addiction population. Of significance we found evidence of consumption of an illicit new psychoactive benzodiazepine, Etizolam. Introduction Benzodiazepines are useful in the short-term treatment of anxiety and insomnia, and in managing alcohol withdrawal. 1 According to the EMCDDA report on the misuse of benzodiazepines among high-risk opioid users in Europe1, benzodiazepines, especially when injected, can prolong the intensity and duration of opioid effects. -

The Waterloo Wellington Palliative Sedation Protocol

The Waterloo Wellington Palliative Sedation Protocol Waterloo Wellington Interdisciplinary HPC Education Committee; PST Task Force Chair: Dr. Deborah Robinson MD CCFP(F), Focused practice in Oncology and Palliative Care Co-chairs: Cathy Joy, Palliative Care Consultant, Waterloo Region Chris Bigelow, Palliative Care Consultant, Wellington County Revision due: November 2016 Last revised and activated: November 13, 2013 Committee responsible for revisions: WW Interdisciplinary HPC Education Committee Table of Contents Purpose and Definitions .................................................................................................................... 2 Indications for the use of PST .............................................................................................................. 3 Criteria for Initiation of PST ............................................................................................................... 4 Process ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Documentation for Initiation of PST .................................................................................................. 5 Medications ......................................................................................................................................... 6 1st Line (Initiating PST) ...................................................................................................................... 6 2nd Line (When 1st -

Midazolam Injection, USP

Midazolam Injection, USP Rx only PHARMACY BULK PACKAGE – NOT FOR DIRECT INFUSION WARNING ADULTS AND PEDIATRICS: Intravenous midazolam has been associated with respiratory depression and respiratory arrest, especially when used for sedation in noncritical care settings. In some cases, where this was not recognized promptly and treated effectively, death or hypoxic encephalopathy has resulted. Intravenous midazolam should be used only in hospital or ambulatory care settings, including physicians’ and dental offices, that provide for continuous monitoring of respiratory and cardiac function, i.e., pulse oximetry. Immediate availability of resuscitative drugs and age- and size-appropriate equipment for bag/valve/mask ventilation and intubation, and personnel trained in their use and skilled in airway management should be assured (see WARNINGS). For deeply sedated pediatric patients, a dedicated individual, other than the practitioner performing the procedure, should monitor the patient throughout the procedures. The initial intravenous dose for sedation in adult patients may be as little as 1 mg, but should not exceed 2.5 mg in a normal healthy adult. Lower doses are necessary for older (over 60 years) or debilitated patients and in patients receiving concomitant narcotics or other central nervous system (CNS) depressants. The initial dose and all subsequent doses should always be titrated slowly; administer over at least 2 minutes and 1 allow an additional 2 or more minutes to fully evaluate the sedative effect. The dilution of the 5 mg/mL formulation is recommended to facilitate slower injection. Doses of sedative medications in pediatric patients must be calculated on a mg/kg basis, and initial doses and all subsequent doses should always be titrated slowly. -

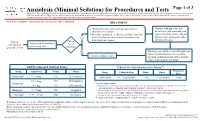

Anxiolysis (Minimal Sedation) for Procedures and Tests

Anxiolysis (Minimal Sedation) for Procedures and Tests Page 1 of 3 Disclaimer: This algorithm has been developed for MD Anderson using a multidisciplinary approach considering circumstances particular to MD Anderson’s specific patient population, services and structure, and clinical information. This is not intended to replace the independent medical or professional judgment of physicians or other health care providers in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine a patient's care. This algorithm should not be used to treat pregnant women. Note: Refer to UTMDACC Institutional Policy #CLN0502 for complete information. TREATMENT ● Document mental status and vital signs prior to Continue with procedure and administering sedation document mental status and vital ● Determine appropriate medication and dose based on signs after administering sedation onset of action (see chart below) of anxiolytic for and prior to beginning procedure Yes 1 desired patient response and post-procedure Patient Patient Assess need for anxiolysis scheduled for needs prior to procedure procedure or test anxiolysis? No Discharge patient when clinically stable and follow institutional processes regarding Continue with procedure discharge instructions and criteria for both inpatient and outpatient settings 2,3 Adult Recommended Anxiolysis Dosing Pediatric Recommended Anxiolysis Dosing3,5,6 Maximum Drug Adult Dose Route Onset Drug Pediatric Dose Route Onset Dose 4 Midazolam 5 – 10 mg PO 10-30 minutes Midazolam 0.5 – 1 mg/kg/dose PO 10-20 minutes 5 mg 0.5 – 2 mg PO 30-60 minutes Lorazepam 5 Pediatric considerations: 1 – 4 mg IM 20-30 minutes ● Consider lower dosing strategies for patients with cardiac or respiratory compromise, and those who received concomitant opiates, benzodiazepines or similar synergistic sedative medications. -

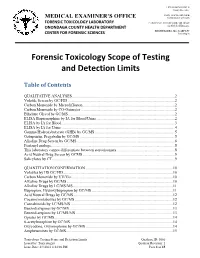

Forensic Toxicology Scope of Testing and Detection Limits

J. RYAN MCMAHON II County Executive INDU GUPTA, MD, MPH MEDICAL EXAMINER’S OFFICE Commissioner of Health FORENSIC TOXICOLOGY LABORATORY CAROLYN H. REVERCOMB, MD, DABP ONONDAGA COUNTY HEALTH DEPARTMENT Chief Medical Examiner KRISTIE BARBA, MS, D-ABFT-FT CENTER FOR FORENSIC SCIENCES Toxicologist Forensic Toxicology Scope of Testing and Detection Limits Table of Contents QUALITATIVE ANALYSES.........................................................................................................2 Volatile Screen by GC/FID .............................................................................................................2 Carbon Monoxide by Microdiffusion..............................................................................................2 Carbon Monoxide by CO-Oximeter ................................................................................................2 Ethylene Glycol by GC/MS.............................................................................................................2 ELISA Buprenorphine by IA for Blood/Urine ................................................................................2 ELISA by IA for Blood ...................................................................................................................3 ELISA by IA for Urine....................................................................................................................4 Gamma Hydroxybutyrate (GHB) by GC/MS..................................................................................5 Gabapentin, -

The Pharmacology of Midazolam and Thiopental with Regard to the Lethal Injection Protocol in the State of Mississippi

Litigation Report – Expert Opinion THE PHARMACOLOGY OF MIDAZOLAM AND THIOPENTAL WITH REGARD TO THE LETHAL INJECTION PROTOCOL IN THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI Re: Mississippi Lethal Injection Case January 15, 2016 Researched and written by: Craig W. Stevens, Ph.D. Professor of Pharmacology Oklahoma State University-Center for Health Sciences 1111 W. 17th Street Tulsa, OK 74107 Prepared for and submitted to: Emily Washington Attorney Roderick & Solange MacArthur Justice Center 4400 S. Carrollton Ave. New Orleans, LA 70119 Expert Report: MISS lethal injection Sections ______________________________________________________________________________ 1. Background and Qualifications of the Author ................................................................... 3 2. Midazolam and Thiopental are not Pharmacologically Equivalent .................................... 3 A. Pharmacological Equivalency and Pharmacological Substitution ....................................... 3 B. Pharmacological Classification of Midazolam and Thiopental ............................................ 4 C. Mechanism of Action of Midazolam and Thiopental ........................................................... 5 D. The Pharmacology of the Partial Agonist, Midazolam, and Full Agonist, Thiopental ......... 6 E. Therapeutic Uses of Benzodiazepines and Barbiturates ...................................................... 8 F. DEA Scheduling of Midazolam and Thiopental..................................................................... 9 G. Summary ............................................................................................................................. -

Benzodiazepines and Dementia

Dementia Q&A 25 Benzodiazepines and dementia Benzodiazepines are a class of drugs commonly used to treat anxiety and insomnia. However, long-term regular treatment with benzodiazepines carries a number of risks. This sheet provides information about how these drugs work as well as the impact that they may have in respect to dementia risk and cognitive functioning. What are benzodiazepines? Benzodiazepines are psychotropic medications (that is, medications that impact on mood and behaviour) that have been in use since the 1960s primarily for the treatment of anxiety, panic disorders and insomnia. They are a ‘depressant’ medication, also known as ‘minor tranquilizers’ and can also be used for treatment of seizures, muscle spasms, alcohol withdrawal and as a preoperative medication for medical or dental procedures. Benzodiazepines are widely available in Australia (Table 1) and are used regularly by around 15% of Australian adults aged 65 years and over.1 Although prescribing rates have fallen over the past decade, there is a continued high rate of prescription among the population.2,3 1 Windle A, Elliot E, Duszynski K, Moore V. Benzodiazepine prescribing in elderly Australian general practice patients. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2007;31(4):379–381. 2 Stephenson CP, Karanges,E, McGreggor IS. Trends in the utilisation of psychotropic medications in Australia from 2000 to 2011. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;47(1):74–87. 3 Islam MM, Conigrave KM, Day CA, Nguyen Y, Haber PS. Twenty-year trends in benzodiazepine dispensing in the Australian population. Internal Medicine Journal. 2014;44(1):57–64. -

![First-Line Anti-Epileptic Medication for Management of Acute Convulsive Seizures, When Intravenous Access Is Available [2015]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7945/first-line-anti-epileptic-medication-for-management-of-acute-convulsive-seizures-when-intravenous-access-is-available-2015-3447945.webp)

First-Line Anti-Epileptic Medication for Management of Acute Convulsive Seizures, When Intravenous Access Is Available [2015]

[2015] EPI 2: First-line anti-epileptic medication for management of acute convulsive seizures, when intravenous access is available [2015] SCOPING QUESTION: In adults with acute convulsive seizures, where intravenous access is available, which first-line anti- epileptic medication should be used to abort seizures when compared to comparator? Back to Table of Contents BACKGROUND Acute convulsive seizures are a medical emergency in adults that commonly present in emergency rooms and require prompt recognition and management. Although most seizures self-terminate within 5 minutes, seizures that last longer than 5–10 minutes are at high risk of continuing for at least 30 minutes. Once a seizure lasts for >5-10 minutes, it is unlikely to stop spontaneously within the next few minutes and so intervention is indicated (Shinnar et al., 2001). The current operational definition of status epilepticus (SE) is ≥5 minutes of continuous seizures or ≥2 discrete seizures without complete recovery of consciousness in between (Lowenstein et al., 2001). The use of this operational definition allows for starting treatment early (within 5-10 minutes). It is also recognized that for a majority of seizures occurring in the out-of-hospital settings it is virtually impossible to ascertain the onset, which makes it very difficult to determine even the approximate duration of the seizure. Therefore, the definition of SE has been expanded to include any patient who is brought convulsing to the emergency room (Lowenstein et al, 2001; Aldredge et al., 2001). Immediate treatment of acute convulsive seizures or SE is crucial to prevent adverse neurologic and systemic consequences. Multiple protocols for management of acute convulsive seizures and SE are available (Mazurkiewicz-Bełdzińska et al., 2014; Hirsch et al., 2013; Claassen et al., 2012; Minicucci et al., 2006). -

Evaluation of Sedation Failure in the Outpatient Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinic Figen Cizmeci Senel, DDS, Phd,* James M

J Oral Maxillofac Surg 65:645-650, 2007 Evaluation of Sedation Failure in the Outpatient Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinic Figen Cizmeci Senel, DDS, PhD,* James M. Buchanan, Jr, DDS,† Ahmet Can Senel, MD,‡ and George Obeid, DDS§ Purpose: Our goal was to report on the incidence of sedation failures in our outpatient oral surgery clinic. Sedation failure is the inability to complete a procedure under intravenous sedation. There is very little in the oral surgery literature on this subject. Materials and Methods: Proper Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the appro- priate governing body for this project. The medical records of 539 intravenous sedation patients treated at the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinic at our institution were retrospectively evaluated to determine the incidence of failed sedation. Patients sedated with midazolam and fentanyl were placed in group A. There were 323 patients in group A. We placed patients sedated with midazolam, fentanyl and methohexital into group B. There were 216 patients in group B. The gender, medical history, type of procedure being performed, amount of drug given, and the patient’s vital signs throughout the proce- dure were recorded. Results: There were 9 failed sedations with a rate of 1.6% (9/539); 3 in group B (1%) and 6 in group A (2%). Five of our failures were undergoing multiple tooth extractions. Two of the failures were undergoing surgical removal of impacted third molars. Two patients underwent mandibular fracture reduction. Failure was attributed to increased agitation and combativeness, uncontrolled hypertension, tachychardia and desaturation. Conclusion: The mandible fracture population and multiple teeth extraction patients had higher rates of failure than other groups. -

350 Prolonged Somnolence and Recovery, Sneezing, Coughing, Mg)

Capital Punishment by Lethal Injection We’ve come a long way, baby – or have we? “Old Sparky” The “Botched” Lethal Injection of Clayton Lockett Presented by: David M. Benjamin, Ph.D., FCLM, FCP, F-AAFS “The Electric Chair” at Sing Sing Prison Which one of you wants to “pull the switch” on Dr. Benjamin? Where the “Deed” is Done! Answer: There’s a group of people lined up to do it! The Texas execution chamber in Huntsville, TX. (Headline: Mark Berman, Photo: Pat Sullivan/AP, Washington Post, March 13, 2016) Lethal Injection ■ Lethal injection is the practice of injecting a person with a fatal dose of drugs (typically a barbiturate, paralytic (i.e., curare-like drug), and potassium solution) for the express purpose of causing immediate, painless (?), death. But ■ Often, it’s not lethal. ■ Often it’s not immediate ■ Often it’s not painless ■ Medical doctors often are not part of the team 1 History of Lethal Injection History of Lethal Injection ■ On May 11, 1977, Oklahoma's state medical examiner, ■ Since then, until 2004, 37 of the 38 states using Jay Chapman, proposed a new, less painful method of execution, known as Chapman's Protocol: capital punishment introduced lethal injection ■ "An intravenous saline drip shall be started in the prisoner's statutes. arm, into which shall be introduced a lethal injection ■ On August 29, 1977, Texas adopted the new consisting of an ultra-short-acting barbiturate in combination with a chemical paralytic." method of execution, switching to lethal ■ After the procedure was approved by anesthesiologist Stanley injection from electrocution. -

Midazolam Compared with Thiopentone As a Hypnotic Component in Balanced Anaesthesia: a Randomized, Double-Blind Study

MIDAZOLAM COMPARED WITH THIOPENTONE AS A HYPNOTIC COMPONENT IN BALANCED ANAESTHESIA: A RANDOMIZED, DOUBLE-BLIND STUDY J.G. REVES, RONALDVINIK, A.M. HIRSCHFIELD,CLIFFORD HOLCOMB, AND SANDRASTRONG MIDAZOLAM is a 1,4-benzodiazepine derivative (Figure 1) synthesized by Walser and Fryer in 1975. Earlier studies with midazolam have dem- onstrated its efficacy for induction of anaes- thesia ~-4 and for intravenous premedication. ~ Midazolam is superior to diazepam for induction of anaesthesia because it causes less burning on injection, is quicker in onset, and there is less individual variation in response to a given dos- DiazelPam (Valium) MiOazolc~rn Maleote age.-' Midazolam is also short acting with a rela- FIGURE 1. Chemical structure of midazolam: 8- tively brief half-life? Most of the advantages of chloro- 6- (2- fluorophenyl)- 1- methyl- 4H- imidazo (-) midazolam over diazepam are a result of its [1, 5-a] [1, 4] benzodiazepine maleate (right) and diazepam: 7- chlorolomethyl- 5- phenyl- 3H- 1,4- greater water solubility. benzodiazepine- 2 (IH)-one (left). Note the imidazole The present investigation compares mida- ring (bold line) substitution in midazolam which contri- zolam with thiopentone for use as the hypnotic butes to increased aqueous solubility. drug in a balanced anaesthesia regimen. Midazolam compares favourably with and has prepared as 2.5 mg base equivalent per ml* and some advantages over thiopentone. thiopentone as 37.5 mg-ml, these ensuring equipotent volumes for induction of anaesthesia METHODS with 0.2 rag. kg midazolam and 3 rag. kg thiopen- tone. Both drugs were shrouded in a 15 cc syringe Fifty patients participated in a double-blind and the appropriate volume was given intraven- comparison of midazolam and thiopentone in a ously for induction over 5-10 seconds while the protocol for balanced anaesthesia.