Mining Sector Development in West Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lessons from Burkina Faso's Thomas Sankara By

Pan-Africanism and African Renaissance in Contemporary Africa: Lessons from Burkina Faso’s Thomas Sankara By: Moorosi Leshoele (45775389) Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: Prof Vusi Gumede (September 2019) DECLARATION (Signed) i | P a g e DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to Thomas Noel Isadore Sankara himself, one of the most underrated leaders in Africa and the world at large, who undoubtedly stands shoulder to shoulder with ANY leader in the world, and tall amongst all of the highly revered and celebrated revolutionaries in modern history. I also dedicate this to Mariam Sankara, Thomas Sankara’s wife, for not giving up on the long and hard fight of ensuring that justice is served for Sankara’s death, and that those who were responsible, directly or indirectly, are brought to book. I also would like to tremendously thank and dedicate this thesis to Blandine Sankara and Valintin Sankara for affording me the time to talk to them at Sankara’s modest house in Ouagadougou, and for sharing those heart-warming and painful memories of Sankara with me. For that, I say, Merci boucop. Lastly, I dedicate this to my late father, ntate Pule Leshoele and my mother, Mme Malimpho Leshoele, for their enduring sacrifices for us, their children. ii | P a g e AKNOWLEDGEMENTS To begin with, my sincere gratitude goes to my Supervisor, Professor Vusi Gumede, for cunningly nudging me to enrol for doctoral studies at the time when the thought was not even in my radar. -

Ore Genesis and Modelling of the Sadiola Hill Gold Mine, Mali Geology Honours Project

ORE GENESIS AND MODELLING OF THE SADIOLA HILL GOLD MINE, MALI GEOLOGY HONOURS PROJECT Ramabulana Tshifularo Student number: 462480 Supervisor: Prof Kim A.A. Hein Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Prof. Kim Hein for giving me the opportunity to be part of her team and, for helping and motivating me during the course of the project. Thanks for your patience, constructive comments and encouragement. Thanks to my family and my friends for the encouragements and support. Table of contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………..i Chapter: 1 1.1 Introduction……………………………………………………..........................................1 1.2 Location and Physiography……………………………………………………………...2 1.3 Aims and Objectives…………………………………………………………………….3 1.4 Abbreviations and acronyms…………………………………………………………….3 Chapter 2 2.1 Regional Geology………………………………………………………………………..4 2.1.1 Geology of the West African Craton…………………………………………………..4 2.1.2 Geology of the Kedougou-Kéniéba Inlier……………………………………………..5 2.2 Mine geology…………………………………………………………………………….6 Lithology………………………………………………………………………………8 Structure……………………………………………………………………………….8 Metamorphism………………………………………………………………………...9 Gold mineralisation and metallogenesis………………………………………………9 2.4 Previously suggested genetic models…………………………………………………..10 Chapter3: Methodology…………………………………………………………………....11 Chapter 4: Host rocks in drill core…......................................................................................13 4.1 Drill core description….........................................................................................................13 -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

RCS Demographics V2.0 Codebook

Religious Characteristics of States Dataset Project Demographics, version 2.0 (RCS-Dem 2.0) CODE BOOK Davis Brown Non-Resident Fellow Baylor University Institute for Studies of Religion [email protected] Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following persons for their assistance, without which this project could not have been completed. First and foremost, my co-principal investigator, Patrick James. Among faculty and researchers, I thank Brian Bergstrom, Peter W. Brierley, Peter Crossing, Abe Gootzeit, Todd Johnson, Barry Sang, and Sanford Silverburg. I also thank the library staffs of the following institutions: Assembly of God Theological Seminary, Catawba College, Maryville University of St. Louis, St. Louis Community College System, St. Louis Public Library, University of Southern California, United States Air Force Academy, University of Virginia, and Washington University in St. Louis. Last but definitely not least, I thank the following research assistants: Nolan Anderson, Daniel Badock, Rebekah Bates, Matt Breda, Walker Brown, Marie Cormier, George Duarte, Dave Ebner, Eboni “Nola” Haynes, Thomas Herring, and Brian Knafou. - 1 - TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Citation 3 Updates 3 Territorial and Temporal Coverage 4 Regional Coverage 4 Religions Covered 4 Majority and Supermajority Religions 6 Table of Variables 7 Sources, Methods, and Documentation 22 Appendix A: Territorial Coverage by Country 26 Double-Counted Countries 61 Appendix B: Territorial Coverage by UN Region 62 Appendix C: Taxonomy of Religions 67 References 74 - 2 - Introduction The Religious Characteristics of States Dataset (RCS) was created to fulfill the unmet need for a dataset on the religious dimensions of countries of the world, with the state-year as the unit of observation. -

Mise En Page 1

[]Annual Report 2004 Legalmentions Published by : IUCN Regional Office for West Africa, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso © 2005 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowled- ged. Citation : IUCN-BRAO (2005). Annual Report 2004, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. 34 pp. ISBN : 2-8317-0851-6 Cover photos : J.F. Hellion N. Van Ingen - FIBA IUCN Jean-Marc GARREAU Louis Gérard d’ESCRIENNE Design and layout by : DIGIT’ART Printed by : Ghana Printing & Packaging Industries LTD Available from : IUCN-regional office for West Africa 01 BP 1618 Ouagadougou 01 Burkina Faso Tél.: (226) 50 32 85 00 Fax : (226) 50 30 75 61 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.iucn.org/brao IUCN []3 []Annual Report 2004 Contents 6 Foreword Substantial Development of the Regional Programme in 2004 8 IUCN donors A Standing Support 10 Four Years in West Africa 10 - Introduction 12 - The Regional Wetlands Programme 15 - Economic and Social Equity as Core Principle of Conservation 18 - Creating Dialogue for Influencing Policies 21 - WAP transboundary Complex Protecting the Environment is “ to guarantee social and economic livelihood 24 West Africa at the Bangkok Congress IUCN-BRAO took part in the Bangkok World Conservation Congress “ of populations in West Africa 26 Programme Development prospects for IUCN West Africa 26 - The New Four-Year Programme 31 - The PRCM is moving forward 32 Annexes 32 - Financial Reports 33 - Recent Publications 33 - List of IUCN Members in West Africa 34 - IUCN Offices []4 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR WEST AFRICA IUCN []5 []Annual Report 2004 West Africa Members, up to date with the Foreword bylaws of the Organisation, were all represented at this meeting. -

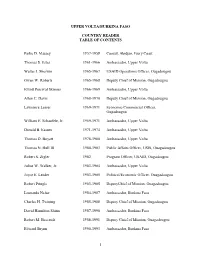

Upper Volta/Burkina Faso Country Reader Table Of

UPPER VOLTA/BURKINA FASO COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Parke D. Massey 1957-1958 Consul, Abidjan, Ivory Coast homas S. Estes 1961-1966 Ambassador, Upper (olta )alter J. Sherwin 1965-1967 USAID ,perations ,ffi.er, ,ugadougou ,wen ). 0oberts 1965-1968 Deputy Chief of Mission, ,ugadougou Elliott Per.ival Skinner 1966-1969 Ambassador, Upper (olta Allen C. Davis 1968-1971 Deputy Chief of Mission, ,ugadougou 2awren.e 2esser 1969-1971 E.onomi.3Commer.ial ,ffi.er, ,ugadougou )illiam E. S.haufele, Jr. 1969-1971 Ambassador, Upper (olta Donald 4. Easum 1971-1975 Ambassador, Upper (olta homas D. 4oyatt 1978-1981 Ambassador, Upper (olta 0obert S. 6igler 1982 Program ,ffi.er, USAID, ,ugadougou Julius ). )alker, Jr. 1988-1985 Ambassador, Upper (olta Joy.e E. 2eader 1988-1985 Politi.al3E.onomi. ,ffi.er, ,uagadougou 2eonardo Neher 1985-1987 Ambassador, 4urkina :aso Charles H. wining 1985-1988 Deputy Chief of Mission, ,ugadougou David Hamilton Shinn 1987-1991 Ambassador, 4urkina :aso 0obert M. 4ee.rodt 1988-1991 Deputy Chief of Mission, ,uagadougou Edward 4rynn 1991-1998 Ambassador, 4urkina :aso PARKE D. MASSEY Consul Abidj n, Ivory Co st (1957-195,- Parke D. Massey was born in New York in 1920. He graduated from Haverford Co ege with a B.A. and Harvard University with an M.P.A. He a so served in the U.S. Army from 1942 to 1946 overseas. After entering the Foreign Service in 1947, Mr. Massey was posted in Me-ico City, .enoa, Abid/an, and .ermany. 0hi e in USA1D, he was posted in Nicaragua, Panama, Bo ivia, Chi e, Haiti, and Uruguay. -

The Mineral Industry of Mali in 1998

THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF MALI By Philip M. Mobbs Gold was the most economically significant mineral the area encompassing the Kéniéba gold district and the commodity produced in Mali during 1998. Gold production exploitation permits at Loulo and Sadiola included Afko Corp. from the Sadiola Hill Mine, the Syama Mine, and artisanal Mali, a subsidiary of Afko Korea Inc., on a Kéniéba area production reached an estimated 25 metric tons. Mali was tied property and African Goldfields Corp., a subsidiary of African for third with Zimbabwe on the list of African gold producers, Selection Mining Corp. of Canada, on the Kofi and the Metedia after South Africa and Ghana. Despite 1998 being a difficult Est concessions. Exploration on the Djlimagara property year for mining companies to raise capital, gold exploration continued as Anglogold (42.5%) joined the venture of Barrick continued during the year in the Birimian Series greenstone Gold Corp. of Canada (42.5%) and the Government (15%). belts in the southern and southwestern parts of the country. Emerging Africa Gold (EAG) Inc. of Canada explored the The gross domestic product (GDP) of landlocked Mali was Mankouke West, the Kourou, and the Siribaya permits. The $2.5 billion in 1997, the latest year for which data are joint venture of Emerging African Gold (75%) and Geo-L of available. The agriculture sector contributed nearly 50% to the Russia (25%) held the Koulo permit. Golden Eagle Mining GDP. Gold accounted for about 36% of the country’s 1997 Ltd. was earning a percentage of African Selection Mining’s exports of $562 million. -

Research Master Thesis

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose? Understanding how and why new ICTs played a role in Burkina Faso’s recent journey to socio-political change Fiona Dragstra, M.Sc. Research Master Thesis Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose? Understanding how and why new ICTs played a role in Burkina Faso’s recent journey to socio-political change Research Master Thesis By: Fiona Dragstra Research Master African Studies s1454862 African Studies Centre, Leiden Supervisors: Prof. dr. Mirjam de Bruijn, Leiden University, Faculty of History dr. Meike de Goede, Leiden University, Faculty of History Third reader: dr. Sabine Luning, Leiden University, Faculty of Social Sciences Date: 14 December 2016 Word count (including footnotes): 38.339 Cover photo: Young woman protests against the coup d’état in Bobo-Dioulasso, September 2015. Photo credit: Lefaso.net and @ful226, Twitter, 20 September 2015 All pictures and quotes in this thesis are taken with and used with consent of authors and/or people on pictures 1 A dedication to activists – the Burkinabè in particular every protest. every voice. every sound. we have made. in the protection of our existence. has shaken the entire universe. it is trembling. Nayyirah Waheed – a poem from her debut Salt Acknowledgements Together we accomplish more than we could ever do alone. My fieldwork and time of writing would have never been as successful, fruitful and wonderful without the help of many. First and foremost I would like to thank everyone in Burkina Faso who discussed with me, put up with me and helped me navigate through a complex political period in which I demanded attention and precious time, which many people gave without wanting anything in return. -

Issue 4 (December, 2019)

Geological Society of Africa Newsletter Volume 9 - Issue 4 (December, 2019) Since the Nobel prize was established, 27 African and African-born persons and African organizations got it. YES Africa can do it !!! Stories inside the issue Africa and Nobel prize CAG28 is approaching Toward a better communication Edited by Tamer Abu-Alam Editor of the GSAf Newsletter In the issue GSAF MATTERS 1 KNOW AFRICA (COVER STORY) 10 GEOLOGY COMIC 11 GEOLOGICAL EXPRESSIONS 11 AFRICAN GEOPARK AND GEOHERITAGE 13 AFRICA'S NOBEL PRIZE WINNERS: A LIST 14 NEWS 23 LITERATURE 30 OPPORTUNITIES 38 CONTACT THE COUNCIL 42 Geological Society of Africa – Newsletter Volume 9 – Issue 4 December 2019 © Geological Society of Africa http://gsafr.org Temporary contact: [email protected] GSAf MATTERS Toward a better and a faster communication among the African community of Geosciences By Tamer Abu-Alam (GSAf newsletter editor and information officer) Information and news should be communicated in a faster way than a newsletter. For example, a deadline to apply for a scholarship can be easily missed if it is not posted to the community at a proper time. As a result, and for better and faster communication among the geological society of Africa, the GSAf will use a Gmail group ([email protected]) to facilitate the communication between society members. Some advice and rules: Since any member can post and all the members will receive your message, please do not overload the society by un-related news. Post only important news that wants immediate action from members. Improper messages can lead its owner to be blocked from posting. -

Table of Contents

UPPER VOLTA/BURKINA FASO COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Parke D. Massey 1957-1958 Consul, Abidjan, Ivory Coast Thomas S. Estes 1961-1966 Ambassador, Upper Volta Walter J. Sherwin 1965-1967 USAID Operations Officer, Ougadougou Owen W. Roberts 1965-1968 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou Elliott Percival Skinner 1966-1969 Ambassador, Upper Volta Allen C. Davis 1968-1970 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou Lawrence Lesser 1969-1971 Economic/Commercial Officer, Ougadougou William E. Schaufele, Jr. 1969-1971 Ambassador, Upper Volta Donald B. Easum 1971-1974 Ambassador, Upper Volta Thomas D. Boyatt 1978-1980 Ambassador, Upper Volta Thomas N. Hull III 1980-1983 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Ouagadougou Robert S. Zigler 1982 Program Officer, USAID, Ougadougou Julius W. Walker, Jr. 1983-1984 Ambassador, Upper Volta Joyce E. Leader 1983-1985 Political/Economic Officer, Ouagadougou Robert Pringle 1983-1985 DeputyChief of Mission, Ouagadougou Leonardo Neher 1984-1987 Ambassador, Burkina Faso Charles H. Twining 1985-1988 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou David Hamilton Shinn 1987-1990 Ambassador, Burkina Faso Robert M. Beecrodt 1988-1991 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ouagadougou Edward Brynn 1990-1993 Ambassador, Burkina Faso 1 PARKE D. MASSEY Consul Abidjan, Ivory Coast (1957-1958) Parke D. Massey was born in New York in 1920. He graduated from Haverford College with a B.A. and Harvard University with an M.P.A. He also served in the U.S. Army from 1942 to 1946 overseas. After entering the Foreign Service in 1947, Mr. Massey was posted in Mexico City, Genoa, Abidjan, and Germany. While in USAID, he was posted in Nicaragua, Panama, Bolivia, Chile, Haiti, and Uruguay. -

On the Trail N°26

The defaunation bulletin Quarterly information and analysis report on animal poaching and smuggling n°26. Events from the 1st July to the 30th September, 2019 Published on April 30, 2020 Original version in French 1 On the Trail n°26. Robin des Bois Carried out by Robin des Bois (Robin Hood) with the support of the Brigitte Bardot Foundation, the Franz Weber Foundation and of the Ministry of Ecological and Solidarity Transition, France reconnue d’utilité publique 28, rue Vineuse - 75116 Paris Tél : 01 45 05 14 60 www.fondationbrigittebardot.fr “On the Trail“, the defaunation magazine, aims to get out of the drip of daily news to draw up every three months an organized and analyzed survey of poaching, smuggling and worldwide market of animal species protected by national laws and international conventions. “ On the Trail “ highlights the new weapons of plunderers, the new modus operandi of smugglers, rumours intended to attract humans consumers of animals and their by-products.“ On the Trail “ gathers and disseminates feedback from institutions, individuals and NGOs that fight against poaching and smuggling. End to end, the “ On the Trail “ are the biological, social, ethnological, police, customs, legal and financial chronicle of poaching and other conflicts between humanity and animality. Previous issues in English http://www.robindesbois.org/en/a-la-trace-bulletin-dinformation-et-danalyses-sur-le-braconnage-et-la-contrebande/ Previous issues in French http://www.robindesbois.org/a-la-trace-bulletin-dinformation-et-danalyses-sur-le-braconnage-et-la-contrebande/ -

Investing in the Minerals Industry in Liberia

ANDS, MIN L ES F O & Y GICAL SU E R LO RV N O E T E Y E S G I R G N I Y M R E IA P R UB E LIC OF LIB Investing in the minerals industry in Liberia liberia No4 cover.indd 1 21/01/2016 09:51:14 Investing in the minerals industry in Liberia: ▪▪ Extensive Archean and Proterozoic terranes highly prospective for many metals and industrial minerals, but detailed geology poorly known. ▪▪ Gold, iron ore and diamonds widespread, with new mines opened since 2013 and other projects in the pipeline. ▪▪ Known potentially economic targets for diamonds, base metals, manganese, bauxite, kyanite, phosphate, etc. ▪▪ Little modern exploration carried out for most mineral commodities with the exception of gold and iron ore. ▪▪ National datasets for geology, airborne geophysics and mineral occurrences available in digital form. ▪▪ Modern mineral licensing system. Introduction The Republic of Liberia is located in West Africa, in Liberia. Furthermore, Liberia is richly endowed bordered by Sierra Leone, Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire with natural resources, including minerals, water and to the south-west by the Atlantic Ocean and forests, and has a climate favourable to (Figure 1). With a land area of about 111 000 km2 agriculture. Since the cessation of hostilities the and a population of nearly 4.1 million much of country has made strenuous efforts to strengthen Liberia is sparsely populated comprising rolling its mineral and agricultural industries, mostly plateaux and low mountains away from a narrow timber and rubber. flat coastal plain. The climate is typically tropical, hot and humid at all times, with most rain falling Mineral resources, especially iron ore, have in the in the summer months.