Library Resources Technical Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case for County Law Library Consortia*

LAW LIBRARY JOURNAL Vol. 111:3 [2019-14] The Case for County Law Library Consortia* Meredith Weston Kostek** This case study looks at the benefits found in joining statewide county law library consortia. Surveys of participating states show benefit use and preferences and indicate that while monetary benefits are found in statewide consortia, the biggest perceived benefit is in collaboration with other libraries in the network. Introduction .........................................................307 Literature Review .....................................................308 Methodology .........................................................310 Consortial History and Results by State ..................................311 California .........................................................311 Ohio ................................................................315 Massachusetts ......................................................319 Discussion ...........................................................322 Conclusion ..........................................................323 Introduction ¶1 Law libraries throughout the United States play an important role in access to justice. These libraries serve not only their local legal communities but also pro se litigants. This is especially true of government libraries, which include state, county, and court libraries. This study focuses on states’ county law libraries, which are frequently autonomous from one another. Would sharing costs, resources, and community knowledge benefit these libraries? -

Collection Development Policy

COLLECTION DEVELOPMENT POLICY JAMES J. LUNSFORD (HILLSBOROUGH COUNTY) LAW LIBRARY Introduction Library Mission Statement The Mission of the Law Library is to collect, maintain and make available legal research materials in print and electronic format not generally obtainable elsewhere in the County for use by the Bench, Bar, students and all Hillsborough County citizens. Definitions “Librarian” means the Senior Librarian of the James J. Lunsford (Hillsborough County) Law Library. “Library” means the James J. Lunsford (Hillsborough County) Law Library or its staff. “Material” or “Materials” means legal or law-related information or resources, regardless of format. For example, subscription databases are “materials.” “Policy” means this Collection Development Policy. Purpose of the Policy The purpose of this Policy is to guide the Library in the selection, acquisition and retention of materials for the Library and to serve as a plan for the overall development of the collection. The Policy establishes priorities in collection, supplementation and retention. The Library’s acquisitions policies are based on the needs of the Library as well as the needs of the community it serves. This Policy must grow and change to meet the needs of the Library and its patrons. Accordingly, this Policy will be reviewed and revised as new resources and technologies become available and old ones disappear, and as the needs of the Library and its patrons demand. Collection Development Principles Responsibility for Selection The Librarian in consultation with the other Library staff, is responsible for the review and selection of materials for purchase. The Librarian will abide by the criteria stated in these guidelines. -

Transforming Acquisitions and Collection Services: Perspectives on Collaboration Within and Across Libraries

Transforming Acquisitions and Collection Services CHARLESTON INSIGHTS IN LIBRARY, ARCHIVAL, AND INFORMATION SCIENCES EDITORIAL BOARD Shin Freedman Tom Gilson Matthew Ismail Jack Montgomery Ann Okerson Joyce M. Ray Katina Strauch Carol Tenopir Anthony Watkinson Transforming Acquisitions and Collection Services Perspectives on Collaboration Within and Across Libraries Edited by Michelle Flinchbaugh Chuck Thomas Rob Tench Vicki Sipe Robin Barnard Moskal Lynda L. Aldana Erica A. Owusu Charleston Insights in Library, Archival, and Information Sciences Purdue University Press West Lafayette, Indiana Copyright 2019 by Purdue University. Printed in the United States of America. Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the Library of Congress. Paper ISBN: 978-1-55753-845-1 Epub ISBN: 978-1-61249-579-8 Epdf ISBN: 978-1-61249-578-1 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-1-55753-847-5. Contents Introduction xi Chuck Thomas PART 1 1 Collaborations Between Acquisitions and Collection Management Edited by Rob Tench CHAPTER 1 5 Collaborative Forecasting When the Crystal Ball Shatters: Using Pilot Programs to Frame Strategic Direction Lynn Wiley and George Gottschalk CHAPTER 2 29 Case Study at The University of Southern Mississippi: Merging the Acquisitions and Collection Management Positions Jennifer R. Culley CHAPTER 3 -

Observations on Scholarly Engagement in the 2008 Cataloging Hidden Special Collections and Archives Program

Observations on Scholarly Engagement in the 2008 Cataloging Hidden Special Collections and Archives Program Council on Library and Information Resources March 2010 Introduction As defined by CLIR, the “Cataloging Hidden Special Collections and Archives” program aims to identify and catalog hidden special collections and archives of “potentially substantive intellectual value that are unknown and inaccessible to scholars.” By providing resources for cataloging key hidden collections and by facilitating the linking of online records, the program also aims “to construct a new research and teaching environment of national importance.” Inherent in the program’s design is a conviction that its success will depend on the ability of the library and archival communities not only to participate actively in the creation of this new environment by processing and cataloging hidden collections, but also by forging new connections with scholars. In a sense, the program is attempting to answer the call of scholars, such as Anthony Grafton, who have written of the pressing need “to bring librarians and scholars, planners and users together…to fashion what we now need … libraries that can regain their place as craft ateliers of scholarship….”1 The “Cataloging Hidden Special Collections and Archives” program is aiming ambitiously to help design, populate, and build these new “ateliers of scholarship,” hybrid physical and digital spaces requiring recalibrations of relationships between librarians, archivists, and scholars. Now entering its third grant cycle, the “Hidden Collections” program is continuing to provide a novel opportunity to observe and describe approaches to scholarly engagement as currently practiced within a diverse set of U.S. libraries and archives. -

Library Resources Technical Services

Library Resources & ISSN 0024-2527 Technical Services October 2008 Volume 52, No. 4 OPAC Queries at a Medium-Sized Academic Library Heather L. Moulaison Literature of Acquisitions in Review, 1996–2003 Barbara S. Dunham and Trisha L. Davis How Much are Technical Services Worth? Philip Hider The Association for Library Collections & Technical Services 52 ❘ 4 The Essential Cataloging and Classification Tools on the Web FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Now includes Spanish and French language interfaces! Cataloger’s Classification Desktop Web Now with The most widely used cataloging Full-text display of much quicker documentation resources in an integrated, all LC classification online system—accessible anywhere. schedules & subject Class Schedule navigation! � Look up a rule in AACR2 and then headings. Updated quickly and easily consult the rule’s daily. LC Rule Interpretation (LCRI). � Find LC/Dewey New! � Includes Describing Archives: A Content Standard. correlations—Match LC classification and subject headings to Dewey® classification � Turn to dozens of cataloging publications numbers as found in LC cataloging records. and metadata resource links plus the complete Use in conjunction with OCLC’s WebDewey® MARC 21 documentation. service for perfect accuracy. � Find what you need quickly with the � Search and navigate across all LC classes or enhanced, simplified user interface. the complete LC subject headings. Free trial accounts & annual Free trial accounts & annual subscription prices: subscription prices: Visit www.loc.gov/cds/desktop www.loc.gov/cds/classweb For free trial, complete the order form at Visit www.loc.gov/cds/desktop/OrderForm.html For free trial, complete the order form at www.loc.gov/cds/classweb/application.html AACR2 is the joint property of the American Library Association, the Canadian Library Association, the Chartered Institute of Library and Dewey and WebDewey are registered trademarks of OCLC, Inc. -

Library Resources Technical Services

Library Resources & ISSN 0024-2527 Technical Services January 2006 Volume 50, No. 1 The Future of Cataloging Deanna Marcum Utilizing the FRBR Framework in Designing User-Focused Digital Content and Access Systems Olivia M. A. Madison Serials Lauren E. Corbett Becoming an Authority on Authority Control Robert E. Wolverton, Jr. Evidence of Application of the DCRB Core Standard in WorldCat and RLIN M. Winslow Lundy Use of General Preservation Assessments Karen E. K. Brown The Association for Library Collections & Technical Services 50 ❘ 1 Library Resources & Technical Services (ISSN 0024-2527) is published quarterly by the American Library Association, 50 E. Huron St., Chicago, IL Library Resources 60611. It is the official publication of the Association for Library Collections & Technical Services, a division of the American Library Association. Subscription price: to members of the Association & for Library Collections & Technical Services, $27.50 Technical Services per year, included in the membership dues; to nonmembers, $75 per year in U.S., Canada, and Mexico, and $85 per year in other foreign coun- tries. Single copies, $25. Periodical postage paid at Chicago, IL, and at additional mailing offices. ISSN 0024-2527 January 2006 Volume 50, No. 1 POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Library Resources & Technical Services, 50 E. Huron St., Chicago, IL 60611. Business Manager: Charles Editorial 2 Wilt, Executive Director, Association for Library Collections & Technical Services, a division of the American Library Association. Send manuscripts Letter to the Editor 4 to the Editorial Office: Peggy Johnson, Editor, Library Resources & Technical Services, University of Minnesota Libraries, 499 Wilson Library, 309 19th Ave. So., Minneapolis, MN 55455; (612) 624- ARTICLES 2312; fax: (612) 626-9353; e-mail: m-john@umn. -

Medical Library Association Mosaic '16 Poster Abstracts

Medical Library Association Mosaic ’16 Poster Abstracts Abstracts for the poster sessions are reviewed by members of the Medical Library Association Joint Planning Committee (JPC), and designated JPC members make the final selection of posters to be presented at the annual meeting. 1 Poster Number: 1 Time: Sunday, May 15, 2016, 2:00 PM – 2:55 PM Painting the Bigger Picture: A Health Sciences Library’s Participation in the University Library’s Strategic Planning Process Adele Dobry, Life Sciences Librarian, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA; Vessela Ensberg, Data Curation Analyst, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Libary, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, Los Angeles, CA; Bethany Myers, AHIP, Research Informationist, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, Los Angeles, CA; Rikke S. Ogawa, AHIP, Team Leader for Research, Instruction, and Collection Services, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Libary, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, Los Angeles, CA; Bredny Rodriguez, Health & Life Sciences Informationist, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, Los Angeles, CA Objectives: To facilitate health sciences participation in developing a strategic plan for the university library that aligns with the university's core mission and directs the library's focus over the next five years. Methods: The accelerated strategic planning process was planned for summer 2015, to be completed by fall 2015. The process was facilitated by bright spot, a consulting group. Seven initial areas of focus for the library were determined: Library Value and Visibility, Teaching and Learning, Research Process, Information and Resource Access, Relationships Within the Library, and Space Effectiveness. Each area of focus was assigned to a working group of 6-8 library staff members. -

Issues of Book Acquisition in University Libraries: a Case Study of Pakistan

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln July 2008 Issues of Book Acquisition in University Libraries: A Case Study of Pakistan Kanwal Ameen Punjab University, Lahore, Pakistan, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Ameen, Kanwal, "Issues of Book Acquisition in University Libraries: A Case Study of Pakistan" (2008). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 198. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/198 Library Philosophy and Practice 2008 ISSN 1522-0222 Issues of Book Acquisition in University Libraries: A Case Study of Pakistan Dr. Kanwal Ameen Assistant Professor Dept. of LIS Punjab University Lahore, Pakistan Introduction Acquiring information resources is a core activity of libraries. University libraries all over the world still acquire and maintain massive book collections while managing other formats. Despite prophecies of vanishing print collections and emergence of the digital paradigm, printed books still have a central role in library collections and publishing industry (Kanwal 2005; Carr 2007) Until 2005, collections in Pakistan's university libraries (UL) mainly consisted of books (foreign), when the Higher Education Commission (HEC) of Pakistan provided access to thousands of digital databases (Government of Pakistan. Higher Education Commission). A doctoral study found that in Pakistan, university libraries annual collection funds are mostly spent on new books and serial publications (Ameen 2005a). These funds have increased each year under the present regime; however, the book market has never been capable of efficiently supplying the imported current and research material for libraries. -

It's Who Libraries Serve

It’s Not What Libraries Hold; It’s Who Libraries Serve Seeking a User-Centered Future for Academic Libraries WHITE PAPER | JANUARY 2020 AUTHORS Gwen Evans, MLIS, MA OhioLINK, Executive Director [email protected] Roger C. Schonfeld Ithaka S+R, Director, Libraries, Scholarly Communication, and Museums [email protected] OhioLINK: In service to your users We are excited to share this white paper, “It’s Not be relevant to address our needs as we enable What Libraries Hold; It’s Who Libraries Serve— users in their research, learning, and teaching. Seeking a User-Centered Future for Academic Libraries,” our next step in envisioning library Through this process, our instincts have proven business needs in the context of integrated library correct: As our members’ scopes of service systems. You, our members, are the first to see continue to widen, integrated library systems it. As a preface, I want to explain its genesis, what maintain a narrow focus on the acquisition, it is and isn’t, and why we think it is important management, and delivery of objects. Our needs to you, your institution, and those you serve. have outpaced existing offerings. Access based on a narrow stream of products is no longer We know the business of higher education is enough. We need systems that support the ROI dramatically changing. Libraries are doing much of higher education institutions and provide great more than managing collections to support value to the range of our users, from students to teaching, learning, and innovative research; world-class researchers. Our focus is enabling we are managing services and products, and their collective activities and aspirations in then some—all while higher education is under their ever-expanding methods and forms. -

Issues in Law Library Acquisitions: an Analysis

Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2000 Issues in Law Library Acquisitions: An Analysis Kent Milunovich Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/faculty Part of the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Kent Milunovich, Issues in Law Library Acquisitions: An Analysis, 92 LAW LIB. J. 203 (2000). https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/faculty/352 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Issues in Law Library Acquisitions: An Analysis* Kent Milunovich** Mr. Milunovich explores issues and trends in the field of acquisitions by reviewing selected library literature and placing it in the context of law libraries. 1 Although journals in the field of librarianship often include articles pertaining to acquisitions, they usually are geared to a broad audience and rarely tailored specifically to law libraries. Some of these articles, however, provide information that is germane to law librarians who work in acquisitions. The purpose of this article is to consider the best of recent writing about acquisitions against the con- text of law libraries. Where appropriate, distinctions are drawn between acquisi- tions in academic and nonacademic law libraries. The topics discussed include shrinking acquisitions resources, changes in legal publishing, building and man- aging an acquisitions program, preservation, outsourcing, gifts, and the Internet. Shrinking Acquisitions Resources 2 Many law libraries have experienced a shrinkage in acquisitions resources in recent years. -

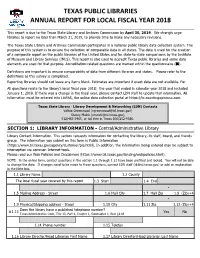

Texas Public Libraries Annual Report for Local Fiscal Year 2018

TEXAS PUBLIC LIBRARIES ANNUAL REPORT FOR LOCAL FISCAL YEAR 2018 This report is due to the Texas State Library and Archives Commission by April 30, 2019. We strongly urge libraries to report no later than March 31, 2019, to provide time to make any necessary revisions. The Texas State Library and Archives Commission participates in a national public library data collection system. The purpose of this system is to ensure the collection of comparable data in all states. The data is used for the creation of a composite report on the public libraries of the United States and for state-to-state comparisons by the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS). This report is also used to accredit Texas public libraries and some data elements are used for that purpose. Accreditation-related questions are marked within the questionnaire (). Definitions are important to ensure comparability of data from different libraries and states. Please refer to the definitions as this survey is completed. Reporting libraries should not leave any items blank. Estimates are important if exact data are not available. For All questions relate to the library's local fiscal year 2018: the year that ended in calendar year 2018 and included January 1, 2018. If there was a change in the fiscal year, please contact LDN staff to update that information. All information must be entered into LibPAS, the online data collection portal at https://tx.countingopinions.com. Texas State Library - Library Development & Networking (LDN) Contacts Valicia Greenwood ([email protected]) Stacey Malek ([email protected]), 512/463-5465, or toll free in Texas 800/252-9386. -

Newark Public Library System Job Description

Job Description Bookmobile Driver/Clerk Department: Outreach Services Reports To: Outreach Supervisor Job Classification: Full-Time, Regular, Non-Exempt, Salary Range $11.00-$18.00/hour Job Summary: The Bookmobile Driver/Clerk prepares and drives the Bookmobile to and from public and private schools, daycares, preschools, senior sites, and community stops; provides library service and interacts with personnel at designated sites/facilities; assists with basic maintenance of the bookmobile, and provides clerical support to the Outreach Supervisor. Mission: We will serve our community by providing fun and educational experiences through our customer- focused staff and technology. The Bookmobile Driver/Clerk supports that mission by ensuring that members of the community (who are unable to come into the Library) have access to that same world of ideas and information via bookmobile and outreach services. Personal & Professional Attributes: All Licking County Library employees are expected to exercise sensitivity when working with others, display common sense and good judgment, actively promote the Library to the public, uphold the highest level of confidentiality, honesty and integrity, and represent the Library in a positive and professional manner at all times. Core Technology Competencies: All Licking County Library employees must have a demonstrated working knowledge of computer operations, standard office equipment (copiers, faxes, etc.) and must be able to perform simple searches on the Library’s online catalog. In addition, all employees must be able to prepare basic documents using a word processing program and have the ability to comprehend and explain to others all Library services including those relating to e-media and e-media devices.