Observations on Scholarly Engagement in the 2008 Cataloging Hidden Special Collections and Archives Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case for County Law Library Consortia*

LAW LIBRARY JOURNAL Vol. 111:3 [2019-14] The Case for County Law Library Consortia* Meredith Weston Kostek** This case study looks at the benefits found in joining statewide county law library consortia. Surveys of participating states show benefit use and preferences and indicate that while monetary benefits are found in statewide consortia, the biggest perceived benefit is in collaboration with other libraries in the network. Introduction .........................................................307 Literature Review .....................................................308 Methodology .........................................................310 Consortial History and Results by State ..................................311 California .........................................................311 Ohio ................................................................315 Massachusetts ......................................................319 Discussion ...........................................................322 Conclusion ..........................................................323 Introduction ¶1 Law libraries throughout the United States play an important role in access to justice. These libraries serve not only their local legal communities but also pro se litigants. This is especially true of government libraries, which include state, county, and court libraries. This study focuses on states’ county law libraries, which are frequently autonomous from one another. Would sharing costs, resources, and community knowledge benefit these libraries? -

Library Resources Technical Services

Library Resources & ISSN 0024-2527 Technical Services January 2006 Volume 50, No. 1 The Future of Cataloging Deanna Marcum Utilizing the FRBR Framework in Designing User-Focused Digital Content and Access Systems Olivia M. A. Madison Serials Lauren E. Corbett Becoming an Authority on Authority Control Robert E. Wolverton, Jr. Evidence of Application of the DCRB Core Standard in WorldCat and RLIN M. Winslow Lundy Use of General Preservation Assessments Karen E. K. Brown The Association for Library Collections & Technical Services 50 ❘ 1 Library Resources & Technical Services (ISSN 0024-2527) is published quarterly by the American Library Association, 50 E. Huron St., Chicago, IL Library Resources 60611. It is the official publication of the Association for Library Collections & Technical Services, a division of the American Library Association. Subscription price: to members of the Association & for Library Collections & Technical Services, $27.50 Technical Services per year, included in the membership dues; to nonmembers, $75 per year in U.S., Canada, and Mexico, and $85 per year in other foreign coun- tries. Single copies, $25. Periodical postage paid at Chicago, IL, and at additional mailing offices. ISSN 0024-2527 January 2006 Volume 50, No. 1 POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Library Resources & Technical Services, 50 E. Huron St., Chicago, IL 60611. Business Manager: Charles Editorial 2 Wilt, Executive Director, Association for Library Collections & Technical Services, a division of the American Library Association. Send manuscripts Letter to the Editor 4 to the Editorial Office: Peggy Johnson, Editor, Library Resources & Technical Services, University of Minnesota Libraries, 499 Wilson Library, 309 19th Ave. So., Minneapolis, MN 55455; (612) 624- ARTICLES 2312; fax: (612) 626-9353; e-mail: m-john@umn. -

Medical Library Association Mosaic '16 Poster Abstracts

Medical Library Association Mosaic ’16 Poster Abstracts Abstracts for the poster sessions are reviewed by members of the Medical Library Association Joint Planning Committee (JPC), and designated JPC members make the final selection of posters to be presented at the annual meeting. 1 Poster Number: 1 Time: Sunday, May 15, 2016, 2:00 PM – 2:55 PM Painting the Bigger Picture: A Health Sciences Library’s Participation in the University Library’s Strategic Planning Process Adele Dobry, Life Sciences Librarian, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA; Vessela Ensberg, Data Curation Analyst, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Libary, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, Los Angeles, CA; Bethany Myers, AHIP, Research Informationist, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, Los Angeles, CA; Rikke S. Ogawa, AHIP, Team Leader for Research, Instruction, and Collection Services, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Libary, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, Los Angeles, CA; Bredny Rodriguez, Health & Life Sciences Informationist, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, Los Angeles, CA Objectives: To facilitate health sciences participation in developing a strategic plan for the university library that aligns with the university's core mission and directs the library's focus over the next five years. Methods: The accelerated strategic planning process was planned for summer 2015, to be completed by fall 2015. The process was facilitated by bright spot, a consulting group. Seven initial areas of focus for the library were determined: Library Value and Visibility, Teaching and Learning, Research Process, Information and Resource Access, Relationships Within the Library, and Space Effectiveness. Each area of focus was assigned to a working group of 6-8 library staff members. -

It's Who Libraries Serve

It’s Not What Libraries Hold; It’s Who Libraries Serve Seeking a User-Centered Future for Academic Libraries WHITE PAPER | JANUARY 2020 AUTHORS Gwen Evans, MLIS, MA OhioLINK, Executive Director [email protected] Roger C. Schonfeld Ithaka S+R, Director, Libraries, Scholarly Communication, and Museums [email protected] OhioLINK: In service to your users We are excited to share this white paper, “It’s Not be relevant to address our needs as we enable What Libraries Hold; It’s Who Libraries Serve— users in their research, learning, and teaching. Seeking a User-Centered Future for Academic Libraries,” our next step in envisioning library Through this process, our instincts have proven business needs in the context of integrated library correct: As our members’ scopes of service systems. You, our members, are the first to see continue to widen, integrated library systems it. As a preface, I want to explain its genesis, what maintain a narrow focus on the acquisition, it is and isn’t, and why we think it is important management, and delivery of objects. Our needs to you, your institution, and those you serve. have outpaced existing offerings. Access based on a narrow stream of products is no longer We know the business of higher education is enough. We need systems that support the ROI dramatically changing. Libraries are doing much of higher education institutions and provide great more than managing collections to support value to the range of our users, from students to teaching, learning, and innovative research; world-class researchers. Our focus is enabling we are managing services and products, and their collective activities and aspirations in then some—all while higher education is under their ever-expanding methods and forms. -

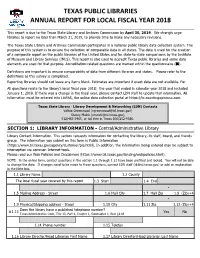

Texas Public Libraries Annual Report for Local Fiscal Year 2018

TEXAS PUBLIC LIBRARIES ANNUAL REPORT FOR LOCAL FISCAL YEAR 2018 This report is due to the Texas State Library and Archives Commission by April 30, 2019. We strongly urge libraries to report no later than March 31, 2019, to provide time to make any necessary revisions. The Texas State Library and Archives Commission participates in a national public library data collection system. The purpose of this system is to ensure the collection of comparable data in all states. The data is used for the creation of a composite report on the public libraries of the United States and for state-to-state comparisons by the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS). This report is also used to accredit Texas public libraries and some data elements are used for that purpose. Accreditation-related questions are marked within the questionnaire (). Definitions are important to ensure comparability of data from different libraries and states. Please refer to the definitions as this survey is completed. Reporting libraries should not leave any items blank. Estimates are important if exact data are not available. For All questions relate to the library's local fiscal year 2018: the year that ended in calendar year 2018 and included January 1, 2018. If there was a change in the fiscal year, please contact LDN staff to update that information. All information must be entered into LibPAS, the online data collection portal at https://tx.countingopinions.com. Texas State Library - Library Development & Networking (LDN) Contacts Valicia Greenwood ([email protected]) Stacey Malek ([email protected]), 512/463-5465, or toll free in Texas 800/252-9386. -

Newark Public Library System Job Description

Job Description Bookmobile Driver/Clerk Department: Outreach Services Reports To: Outreach Supervisor Job Classification: Full-Time, Regular, Non-Exempt, Salary Range $11.00-$18.00/hour Job Summary: The Bookmobile Driver/Clerk prepares and drives the Bookmobile to and from public and private schools, daycares, preschools, senior sites, and community stops; provides library service and interacts with personnel at designated sites/facilities; assists with basic maintenance of the bookmobile, and provides clerical support to the Outreach Supervisor. Mission: We will serve our community by providing fun and educational experiences through our customer- focused staff and technology. The Bookmobile Driver/Clerk supports that mission by ensuring that members of the community (who are unable to come into the Library) have access to that same world of ideas and information via bookmobile and outreach services. Personal & Professional Attributes: All Licking County Library employees are expected to exercise sensitivity when working with others, display common sense and good judgment, actively promote the Library to the public, uphold the highest level of confidentiality, honesty and integrity, and represent the Library in a positive and professional manner at all times. Core Technology Competencies: All Licking County Library employees must have a demonstrated working knowledge of computer operations, standard office equipment (copiers, faxes, etc.) and must be able to perform simple searches on the Library’s online catalog. In addition, all employees must be able to prepare basic documents using a word processing program and have the ability to comprehend and explain to others all Library services including those relating to e-media and e-media devices. -

Teaching and User Satisfaction in an Academic Chat Reference Consortium

Communications in Information Literacy Volume 14 Issue 2 Article 2 12-2020 Teaching and User Satisfaction in an Academic Chat Reference Consortium Kathryn Barrett University of Toronto Scarborough Library, University of Toronto Libraries, [email protected] Judith Logan John P. Robarts Library, University of Toronto Libraries, [email protected] Sabina Pagotto Scholars Portal, Ontario Council of University Libraries, [email protected] Amy Greenberg Scholars Portal, Ontario Council of University Libraries, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/comminfolit Let us know how access to this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Barrett, K., Logan, J., Pagotto, S., & Greenberg, A. (2020). Teaching and User Satisfaction in an Academic Chat Reference Consortium. Communications in Information Literacy, 14 (2), 181–204. https://doi.org/ 10.15760/comminfolit.2020.14.2.2 This open access Research Article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). All documents in PDXScholar should meet accessibility standards. If we can make this document more accessible to you, contact our team. Barrett et al.: Teaching and User Satisfaction in an Academic Chat Reference Consortium COMMUNICATIONS IN INFORMATION LITERACY | VOL. 14, NO. 2, 2020 181 Teaching and User Satisfaction in an Academic Chat Reference Consortium Kathryn Barrett, University of Toronto Judith Logan, University of Toronto Sabina Pagotto, Ontario Council of University Libraries Amy Greenberg, Ontario Council of University Libraries Abstract This study investigated 299 chat reference interactions from an academic library consortium for instances of teaching and compared these against other characteristics of the chat, such as question content, staff type, user status, user satisfaction, institutional affiliation, length, and shift busyness. -

Criteria for Eligibility

Public Library Determination – Eligible Public Library Determination – Eligible Academic Library Determination – Eligible Library Consortium Determination – Eligible Library Kiosk Determination – Eligible Bookmobile/Outreach Vehicle Determination The Kentucky Department for Libraries & Archives makes determination of “public library”; “eligible public library”; “eligible academic library”; “eligible library consortium”; “eligible library kiosk” and “eligible library bookmobile/outreach vehicle” status for LSTA, E-rate, state aid and other purposes based upon the following criteria. In case of doubt, the commissioner or his designates has final authority to issue such a determination. Determination Criteria: 1) A "Public Library" provides free access to all residents of a county, district, or region, without discrimination. It also meets the following minimum criteria: 1(a) the library is established under one of following statutory sections: KRS 65.182, KRS 65.210, KRS 65.810, KRS 67.715, KRS 173.010, KRS 173.310, KRS 173.470, or KRS 173.710. 1(b) the library has an organized collection of printed or other library materials, or a combination thereof; 1(c) the library has paid, trained staff; 1(d) the library has an established schedule during which services of the staff are available to the public; 1(e) the library has the facilities necessary to support such a collection, staff, and schedule; 1(f) the library is supported in whole or in part with public funds. 2) An “Eligible Public Library” is an entity which: 2(a) meets the definition -

Lessons Learned from PALCI's DDA Pilot Projects and Next Steps

Collaborative Librarianship Volume 8 Issue 2 Article 7 2016 Towards the Collective Collection: Lessons Learned from PALCI’s DDA Pilot Projects and Next Steps Jeremy Garskof Gettysburg College, [email protected] Jill Morris PALCI, [email protected] Tracie Ballock Duquesne University, [email protected] Scott Anderson Millersville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/collaborativelibrarianship Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Garskof, Jeremy; Morris, Jill; Ballock, Tracie; and Anderson, Scott (2016) "Towards the Collective Collection: Lessons Learned from PALCI’s DDA Pilot Projects and Next Steps," Collaborative Librarianship: Vol. 8 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/collaborativelibrarianship/vol8/iss2/7 This Peer Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Collaborative Librarianship by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Garskof, et al.: Towards the Collective Collection Towards the Collective Collection: Lessons Learned from PALCI’s DDA Pilot Projects and Next Steps Jeremy Garskof ([email protected]) Acquisitions Librarian, Gettysburg College Jill Morris ([email protected]) Senior Program Officer, PALCI Tracie Ballock ([email protected]) Head of Collection Management, Duquesne University Scott Anderson ([email protected]) Information Systems Librarian, Millersville University Abstract The Pennsylvania Academic Library Consortium, Inc. (PALCI) developed demand-driven acquisition (DDA) programs to facilitate resource sharing of e-monographs and to build collective ebook collections thereby complementing E-ZBorrow, the consortium’s print-based ILL service. -

A Summary of the School Libraries Master Plan

The Future of Delaware School Libraries A Summary of the School Libraries Master Plan August 2017 Specifically, a South Carolina study discovered This policy brief by the Institute for that the presence of a certified librarian positively Public Administration was prepared for affected English Language Arts test scores as well the Partnership for Public Education as the development of research and writing skills and summarizes the key findings and (Lance, Rodney, and Schwarz, 2014). Research such recommendations of the Delaware School as this emphasizes the importance of a full-time Libraries Master Plan. The Master Plan certified librarian. However, other assets of a quality examines years of scholarly research that library also lead to student success. A 2012 study cites the linkage between quality school in Pennsylvania found that schools with quality libraries and student success. Student success libraries were two-to-five times more likely to have refers to higher reading and writing tests students receive an “advanced” score on the state’s scores, increased literacy skills, and higher standardized writing test than ones that did not graduation rates. The Master Plan addresses (Lance and Schwarz, 2012). In addition, a study the disparities between the impact school titled Certified Teacher Librarians, Library Quality libraries could have and the impact they are and Student Achievement in Washington State Public currently having in the state. The Master Plan Schools ranked school libraries using a library quality concludes by examining the state of Delaware scale (LQS), which took into account factors such as school libraries and making recommendations staffing, collection, and scheduling. -

Law Library Consortium in Metro Manila: a Proposed Model and the Management of Law Libraries

407 Chapter 19 Law Library Consortium in Metro Manila: A Proposed Model and the Management of Law Libraries Tadz Majal Ayesha Verdote Jaafar Office of the Solicitor General, Philippines ABSTRACT This chapter gives an overview of special libraries, the management of special libraries, law libraries, and their management and administration. It discusses how the five managerial functions are exercised in law libraries in the Philippines based on the data in the study of the author. It also illustrates the need of the law libraries to collaborate, and discusses the model of a law library consortium proposed by Jaafar (2012). The views of the administrators of the parent institutions of the participant law libraries on their libraries and the propose consortium (based on the said study) are also discussed. At the end of the chapter, some of the recommendations in the aforementioned study were adopted and updated based on the emerging trends and other references for further studies. INTRODUCTION People who conduct research on a certain topic have a number of ways to obtain knowledge and facts regarding their query. Visiting libraries or information centers, and surfing the Internet are among the various techniques which the researchers employ to gather information. Doing these two information gathering activities are almost imperative for the researchers before resorting to other methods of obtain- ing information. But the information needs of the clients vary depending on a number of factors and/ or purposes such as age, educational background, academic/scholastic requirements, occupational, and professional requirements. They obtain information from various sources, but some of what they need could only be found in specific sources. -

Medical Library Association MLA '20 Poster Abstracts

MLA ’20 Poster Abstracts Medical Library Association MLA ’20 Poster Abstracts Abstracts for the poster sessions are reviewed by members of the Medical Library Association National Program Committee (NPC), and designated NPC members make the final selection of posters to be presented at the annual meeting. 1 MLA ’20 Poster Abstracts Poster Number: 1 Time: Friday, July 24, 10:30 a.m.–4:30 p.m. Developing an Evidence-Based Practice Tool in Accord with the Next-Generation Search Interfaces Vivian Chiang, Student, EMBA of National Chengchi University Background: In response to the demand of 2-year Post Graduate Year Training, which was established for the first new graduate of medical schools in XXX, for the implementation of EBP and Shared Decision Making, as well as the trend of cultivating nurse practitioners to carry out EBP, the medical libraries in XXX provide evidence-based literature retrieval skill training. However, most of the interface provided by the database is Google-like, which is different from the PICO framework. Therefore, this project hopes to create a tool to use the PICO framework to retrieve the most precise literature without having the advance research skill. Description: The concept of interface design is based on PICO framework. With the function of mapping with medical subject heading, it helps users to increase the correctness of search strategy and also revised search strategy simultaneously. In addition, in order to meet the clinical needs, the clinical cases related elements such as age, gender, pregnancy, etc. are also provided in the literature filters; the conditions for selecting evidence-based literature are also provided, such as clinical queries, publication types, language, etc.