Imperatives for Post-Conflict Reconstruction in Libya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libya: Protect Vulnerable Minorities & Assist Civilians Harmed

Libya: Protect Vulnerable Minorities & Assist Civilians Harmed • The Libyan authorities should work with UNSMIL, IOM, the U.S., and other donors to provide protec- tion for displaced sub-Saharan Africans, including through the adoption of migrant-friendly policies and compliance with human rights obligations. • The Libyan authorities should work with UNSMIL, the U.S., and other donors to protect displaced dark-skinned Libyans, foster reconciliation, and provide long-term solutions for them. • The Libyan authorities should request NATO’s, the U.S’s, and UNSMIL’s long-term commitment, and technical and financial assistance to develop an effective security sector capable of protecting civil- ians. • NATO must fully and transparently investigate, and when appropriate make amends for civilian harm incurred as a result of its military operations in Libya. Similarly, the Libyan authorities should ensure all civilian conflict-losses are accounted for and amends offered to help civilians recover. With the death of Muammar Gaddafi a long-standing dictatorship has come to an end. The majority of Libyans are celebrating a new future; but certain groups, including suspected loyalist civilians, sub-Saharan Africans, and ethnic minorities remain displaced and vulnerable to violent attacks. The National Transitional Council (NTC) – the current de facto government of Libya – lacks command and control over all armed groups, including those responsible for revenge attacks. As such, the NTC cannot yet establish or maintain the rule of law. The plight of these vulnerable civilians foreshadows challenges to reconciliation, integration, and equal treatment of all in the new Libya. Further, civilians suffering losses during hostilities have not been properly recognized or assisted. -

Libyan Municipal Council Research 1

Libyan Municipal Council Research 1. Detailed Methodology 2. Participation 3. Awareness 4. Knowledge 5. Communication 6. Service Delivery 7. Legitimacy 8. Drivers of Legitimacy 9. Focus Group Recommendations 10. Demographics Detailed Methodology • The survey was conducted on behalf of the International Republican Institute’s Center for Insights in Survey Research by Altai Consulting. This research is intended to support the development and evaluation of IRI and USAID/OTI Libya Transition Initiative programming with municipal councils. The research consisted of quantitative and qualitative components, conducted by IRI and USAID/OTI Libya Transition Initiative respectively. • Data was collected April 14 to May 24, 2016, and was conducted over the phone from Altai’s call center using computer-assisted telephone technology. • The sample was 2,671 Libyans aged 18 and over. • Quantitative: Libyans from the 22 administrative districts were interviewed on a 45-question questionnaire on municipal councils. In addition, 13 municipalities were oversampled to provide a more focused analysis on municipalities targeted by programming. Oversampled municipalities include: Tripoli Center (224), Souq al Jumaa (229), Tajoura (232), Abu Salim (232), Misrata (157), Sabratha (153), Benghazi (150), Bayda (101), Sabha (152), Ubari (102), Weddan (101), Gharyan (100) and Shahat (103). • The sample was post-weighted in order to ensure that each district corresponds to the latest population pyramid available on Libya (US Census Bureau Data, updated 2016) in order for the sample to be nationally representative. • Qualitative: 18 focus groups were conducted with 5-10 people of mixed employment status and level of education in Tripoli Center (men and women), Souq al Jumaa (men and women), Tajoura (men), Abu Salim (men), Misrata (men and women), Sabratha (men and women), Benghazi (men and women), Bayda (men), Sabha (men and women), Ubari (men), and Shahat (men). -

Nationwide School Assessment Libya Ministry

Ministry of Education º«∏©àdGh á«HÎdG IQGRh Ministry of Education Nationwide School Assessment Libya Nationwide School Assessment Report - 2012 Assessment Report School Nationwide Libya LIBYA Libya Nationwide School Assessment Report 2012 Libya Nationwide School Assessment Report 2012 º«∏©àdGh á«HÎdG IQGRh Ministry of Education Nationwide School Assessment Libya © UNICEF Libya/2012-161Y4640/Giovanni Diffidenti LIBYA: Doaa Al-Hairish, a 12 year-old student in Sabha (bottom left corner), and her fellow students during a class in their school in Sabha. Doaa is one of the more shy girls in her class, and here all the others are raising their hands to answer the teacher’s question while she sits quiet and observes. The publication of this volume is made possible through a generous contribution from: the Russian Federation, Kingdom of Sweden, the European Union, Commonwealth of Australia, and the Republic of Poland. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the donors. © Libya Ministry of Education Parts of this publication can be reproduced or quoted without permission provided proper attribution and due credit is given to the Libya Ministry of Education. Design and Print: Beyond Art 4 Printing Printed in Jordan Table of Contents Preface 5 Map of schools investigated by the Nationwide School Assessment 6 Acronyms 7 Definitions 7 1. Executive Summary 8 1.1. Context 9 1.2. Nationwide School Assessment 9 1.3. Key findings 9 1.3.1. Overall findings 9 1.3.2. Basic school information 10 1.3.3. -

The Human Conveyor Belt : Trends in Human Trafficking and Smuggling in Post-Revolution Libya

The Human Conveyor Belt : trends in human trafficking and smuggling in post-revolution Libya March 2017 A NETWORK TO COUNTER NETWORKS The Human Conveyor Belt : trends in human trafficking and smuggling in post-revolution Libya Mark Micallef March 2017 Cover image: © Robert Young Pelton © 2017 Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Global Initiative. Please direct inquiries to: The Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime WMO Building, 2nd Floor 7bis, Avenue de la Paix CH-1211 Geneva 1 Switzerland www.GlobalInitiative.net Acknowledgments This report was authored by Mark Micallef for the Global Initiative, edited by Tuesday Reitano and Laura Adal. Graphics and layout were prepared by Sharon Wilson at Emerge Creative. Editorial support was provided by Iris Oustinoff. Both the monitoring and the fieldwork supporting this document would not have been possible without a group of Libyan collaborators who we cannot name for their security, but to whom we would like to offer the most profound thanks. The author is also thankful for comments and feedback from MENA researcher Jalal Harchaoui. The research for this report was carried out in collaboration with Migrant Report and made possible with funding provided by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway, and benefitted from synergies with projects undertaken by the Global Initiative in partnership with the Institute for Security Studies and the Hanns Seidel Foundation, the United Nations University, and the UK Department for International Development. About the Author Mark Micallef is an investigative journalist and researcher specialised on human smuggling and trafficking. -

International Medical Corps in Libya from the Rise of the Arab Spring to the Fall of the Gaddafi Regime

International Medical Corps in Libya From the rise of the Arab Spring to the fall of the Gaddafi regime 1 International Medical Corps in Libya From the rise of the Arab Spring to the fall of the Gaddafi regime Report Contents International Medical Corps in Libya Summary…………………………………………… page 3 Eight Months of Crisis in Libya…………………….………………………………………… page 4 Map of International Medical Corps’ Response.…………….……………………………. page 5 Timeline of Major Events in Libya & International Medical Corps’ Response………. page 6 Eastern Libya………………………………………………………………………………....... page 8 Misurata and Surrounding Areas…………………….……………………………………… page 12 Tunisian/Libyan Border………………………………………………………………………. page 15 Western Libya………………………………………………………………………………….. page 17 Sirte, Bani Walid & Sabha……………………………………………………………………. page 20 Future Response Efforts: From Relief to Self-Reliance…………………………………. page 21 International Medical Corps Mission: From Relief to Self-Reliance…………………… page 24 International Medical Corps in the Middle East…………………………………………… page 24 International Medical Corps Globally………………………………………………………. Page 25 Operational data contained in this report has been provided by International Medical Corps’ field teams in Libya and Tunisia and is current as of August 26, 2011 unless otherwise stated. 2 3 Eight Months of Crisis in Libya Following civilian demonstrations in Tunisia and Egypt, the people of Libya started to push for regime change in mid-February. It began with protests against the leadership of Colonel Muammar al- Gaddafi, with the Libyan leader responding by ordering his troops and supporters to crush the uprising in a televised speech, which escalated the country into armed conflict. The unrest began in the eastern Libyan city of Benghazi, with the eastern Cyrenaica region in opposition control by February 23 and opposition supporters forming the Interim National Transitional Council on February 27. -

The Sirte Basin Province of Libya—Sirte-Zelten Total Petroleum System

The Sirte Basin Province of Libya—Sirte-Zelten Total Petroleum System By Thomas S. Ahlbrandt U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 2202–F U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Charles G. Groat, Director Version 1.0, 2001 This publication is only available online at: http://geology.cr.usgs.gov/pub/bulletins/b2202-f/ Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government Manuscript approved for publication May 8, 2001 Published in the Central Region, Denver, Colorado Graphics by Susan M. Walden, Margarita V. Zyrianova Photocomposition by William Sowers Edited by L.M. Carter Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Abstract................................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgments............................................................................................................................... 2 Province Geology................................................................................................................................. 2 Province Boundary.................................................................................................................... -

Agriculture and Rural Livelihoods Needs Assessment – Libya 1 1

Agriculture and Rural Livelihoods Needs Assessment – Libya 1 1 Agriculture and Rural Livelihoods Needs Assessment – Libya 2 Agriculture and Rural Livelihoods Needs Assessment – Libya Agriculture and Rural Livelihoods Needs Assessment – Libya 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In the aftermath of the 2011 fall of Muammar Gaddafi’s rule in Libya, a power struggle for control of the country developed into an ongoing civil war, resulting in population displacements and disrupting household livelihoods. In addition to the conflict, Libya’s location and internal political instability caused the country to become a key transitory point for African and Middle Eastern migrants traveling to Europe. Previous studies indicate that foreign migrants have historically played a key role in agricultural labor work within the country. In order to develop and implement future interventions to support Libya’s agricultural sector, information is needed relating to the impacts of the ongoing political crisis on the sector (for local, displaced, and migrant populations), current needs, and entry points for agriculture support programs. To fill this information gap, FAO conducted a rapid agricultural needs assessment in August 2017. Key findings The findings of this study show that agriculture still represents an important source of income in rural areas, with notable regional variations. In the east and south, the population heavily depends on salaries and pensions provided by the government or private sector, while agricultural activities are generally considered secondary income sources. In the west, meanwhile, there is a higher dependency on agriculture as an income source as these areas have some larger scale farms. Eastern, southern and western districts alike hold a strong potential to enhance their agricultural production. -

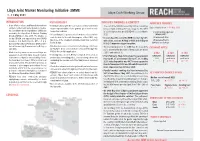

Libya Joint Market Monitoring Initiative (JMMI) Libya Cash Working Group 1 - 11 May 2021

Libya Joint Market Monitoring Initiative (JMMI) Libya Cash Working Group 1 - 11 May 2021 INTRODUCTION METHODOLOGY JMMI KEY FINDINGS & CONTEXT JMMI KEY FIGURES • In an effort to inform cash-based interventions • Field staff familiar with the local market conditions identified • The cost of the MEB increased by 0.5% across Libya Data collection from 1 - 11 May 2021 and better understand market dynamics in Libya, shops representative of the general price level in their between April and May 2021 (see page 2). The MEB the Joint Market Monitoring Initiative (JMMI) was respective locations. is 12.3% higher than pre-COVID-19 levels in March 2 participating agencies created by the Libya Cash & Markets Working • At least four prices per assessed item were collected within 2020. (REACH, WFP) Group (CMWG) in June 2017. The initiative is each location. In line with the purpose of the JMMI, only 32 assessed cities led by REACH and supported by the CMWG • In east Libya, the cost of the MEB has risen by 5.4% the price of the cheapest available brand was recorded 45 assessed items members. It is funded by the Office of U.S. with cities, such as Al Marj (+14.9) and Al Bayda 634 assessed shops Bureau of Humanitarian Assistance (BHA) and the for each item. (+10.2%) experiencing price spikes. • Enumerators were trained on methodology and tools United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees • The food proportion of the MEB has decreased by EXCHANGE RATES1 (UNHCR). by REACH. Data collection was conducted through the 8.2%, driven by the decrease of items, such as onions KoBoCollect mobile application. -

LIBYA: Libya Administrative Map

LIBYA: Libya Administrative Map AL JIFARAH TRIPOLI AL JABAL AN NUQAT Az Zawiyah AL MARJ AL AKHDAR Abu Kammash AL KHAMS Ra's Ajdir !( !( !( AL MARQAB ⛡ Al Baydah Zaltan Mediterranean Sea !( Zuwarah Tripoli Ra's al Hamamah !( Tripoli !( !(!( !( ⛡ !(!( !( !( !( !(!(!( !( !( !( Al Bayda !( Al Athrun Riqdalin !( !( ⛡!(!( !( ⛜!( !(!( Azzawiya \ Susah !( Al Assah!( !( Janzur !( !( !( !( !( Mansur!(ah!( !( !( !( ⛡ !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( Darnah Al Jumayl !( !( Zawiyat al `Urqub !( !( Suq ad Dawawidah !( !( !( !( !( !(!(!( !( !(!( !( ⛡!( !( Al Fatih !( !( A⛜l Abraq !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( ⛡Derna !( !( !( !( !( !(!( !( Qasr Khiyar !(!(!( Al Khums !(!( QabilatS alimah !( Qaryat Sidi Shahir ad Din !( !( !(!( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( Ahqaf a!(l Jabhiya!(h ⛜ !( !( !( !( !( !(!( !( !(!( !(!( !(!( Suq al Khamis !( !( !(!( !( !( !( !( !( Martubah!( Suq as Sab!( t !(!(!( !( !( Al Uwayliyah ash Sha!( rqiyah!( Qasr Libiya !(Zawiyat Umm Hufayn !( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( Al Aquriyah Khadra' !( !( !( Umm ar Rizam Al Watyah!( !( !( !( !( Al Bumbah North Air Base TUNISIA !( !(!( !( !( !(!( !( Okba Ibn Nafa Air Base !( !( Ki`am !(!( ⛜ Asbi`ah !( !(!( !( !( !( !( Misratah Al!( Mabni Qabilat al Kawarighiliyah !( !( ⛜ !( !( !( Marawah !( !( AlH uwayjat !( !( !(!(!(!(!(!(!(!(!( Tansulukh!( !( !( ⛡!(!(!(!(!(!(!(!(M!(!( isurata !( !( QaryatB uR uwayyah !( !( !(!(!(!(!(!( !( !( !( !( !( !( !( At Tamimi!( !( Mintaqat ad Daghdughi !( Bamba Bi'r al Ghanam Bu Ghaylan !(!( !( Qaryat ar Rus !( Al M!( arj !(!(!( !(!(!( !(!(!( !(!( !(!( !( !( !( !( Zawiyat al `Izziyat!( -

Health Response to COVID-19 in Libya WHO Update # 24 Reporting Period

Health response to COVID-19 in Libya WHO update # 24 Reporting period: 1 to 28 February 2021 Figure 1. Cases and 14-day moving average for Libya till week 9 ending 28 February 2021. Figure 2 Comparison of COVID-19 lab tests against cases for Libya till week 9 ending 28 February 2021. 1 | P a g e Figure 3 Mantika level COVID-19 testing (cumulative) for Libya as of February 2021 Figure 4 Geographical distribution of 29 functional COVID-19 testing laboratories across Libya as of February 2021 Highlights o The WR and her team travelled to Benghazi, Sirt, Sousa and Al Bayda. They visited health facilities and met with health authorities, hospital managers and members of local COVID-19 committees to review services and assess needs. Although WHO has been sending regular supplies of PPE, health facilities reported they were still facing severe shortages of items, particularly gloves. WHO has arranged for additional supplies to be dispatched urgently. A detailed report will be issued at the end of the mission. 2 | P a g e o The Presidential Council of the Scientific Committee has endorsed the National Deployment and Vaccination Plan. WHO has urged the national authorities to consider covering the costs of vaccines for over 570 000 migrants and refugees in the country. o Libya has missed out on the first round of COVAX vaccines because it did not submit key documents on time. The Government of National Authority (GNA) has issued a decree authorizing the MOH to sign a bilateral agreement for the direct procurement of vaccines from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson. -

Report Libya: Security Situation

Report Libya: Security Situation 19 December 2014 DISCLAIMER This report is written by country analysts from Belgium, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden. It covers topics that are relevant for status determination of Libyan and non- Libyan citizens whose asylum claims are based on the situation in Libya. The target audience is case workers/officers within the decision-making authorities handling asylum claims as well as policy makers in the four countries. The report is based on carefully selected and referenced sources of information. To the extent possible and unless otherwise stated, all information presented, except for undisputed or obvious facts, has been cross-checked. While the information contained in this report has been researched, evaluated and analysed with utmost care, this document does not claim to be exhaustive, neither is it conclusive as to the determination or merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Terminology used should not be regarded as indicative of a particular legal position. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. The research for this report was finalised in November 2014 and any event or development that has taken place after this date is not included in the report. Report Libya: Security Situation 19 December 2014 2 CONTENTS 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 5 2. Political Context .................................................................................................................... -

Dissertation Isotope and Noble Gas Study of Three

DISSERTATION ISOTOPE AND NOBLE GAS STUDY OF THREE AQUIFERS IN CENTRAL AND SOUTHEAST LIBYA Submitted by Mohamed S. E. Al Faitouri Department of Geosciences In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2013 Doctoral Committee: Advisor: William Sanford Michael Ronayne Steven Fassnacht Reagan Waskom Copyright by Mohamed S. E. Al Faitouri 2013 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT ISOTOPE AND NOBLE GAS STUDY OF THREE AQUIFERS IN CENTRAL AND SOUTHEAST LIBYA Libya suffers from a shortage in water resources due to its arid climate. The annual precipitation in Libya is less than 200 mm in the narrow coastal plain, while the southern part of the country receives less than 1mm. On the other hand, Libya has large resources of good quality groundwater distributed in six basin systems beneath the Sahara. In 1983, the Libyan government established the Great Man-Made River Authority (GMRA) in order to transport 6.5 million cubic meters a day of this groundwater to the coastal cities, where over 90% of the population lives. This large water extraction of one million cubic meters per day (or greater) from each wellfield has the potential to greatly stress the water resources in these areas. This study focuses on three GMRA wellfields in two sedimentary basins (Sirt and Al Kufra) in central and southeast Libya. The Sarir wellfield is located within the Sirt basin and consists of 126 production wells; the Tazerbo wellfield in the Al Kufra basin has 108 wells; and the proposed Al Kufra wellfield is also in the Al Kufra Basin and will have 300 production wells.