Some Forms and Functions of Contrast in the Islendingasogur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

Gender and Fairy Tales

Issue 2013 44 Gender and Fairy Tales Edited by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier ISSN 1613-1878 About Editor Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier Gender forum is an online, peer reviewed academic University of Cologne journal dedicated to the discussion of gender issues. As English Department an electronic journal, gender forum offers a free-of- Albertus-Magnus-Platz charge platform for the discussion of gender-related D-50923 Köln/Cologne topics in the fields of literary and cultural production, Germany media and the arts as well as politics, the natural sciences, medicine, the law, religion and philosophy. Tel +49-(0)221-470 2284 Inaugurated by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier in 2002, the Fax +49-(0)221-470 6725 quarterly issues of the journal have focused on a email: [email protected] multitude of questions from different theoretical perspectives of feminist criticism, queer theory, and masculinity studies. gender forum also includes reviews Editorial Office and occasionally interviews, fictional pieces and poetry Laura-Marie Schnitzler, MA with a gender studies angle. Sarah Youssef, MA Christian Zeitz (General Assistant, Reviews) Opinions expressed in articles published in gender forum are those of individual authors and not necessarily Tel.: +49-(0)221-470 3030/3035 endorsed by the editors of gender forum. email: [email protected] Submissions Editorial Board Target articles should conform to current MLA Style (8th Prof. Dr. Mita Banerjee, edition) and should be between 5,000 and 8,000 words in Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (Germany) length. Please make sure to number your paragraphs Prof. Dr. Nilufer E. Bharucha, and include a bio-blurb and an abstract of roughly 300 University of Mumbai (India) words. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

Speech Acts and Violence in the Sagas*

FREDERIC AMORY Speech Acts and Violence in the Sagas* “Tunga er hçfuôs bani” (“The tongue is the death of the head”) Old Icelandic proverb The American sociolinguist William Labov, who has been collecting and studying anecdotal narratives of street life among gangs of black youths in Harlem and the Philadelphia slums, also published a short paper (Labov, 1981) on the interaction of verbal behavior and violence in the experiences of white informants of his from other areas. As I have pointed out once before (Amory, 1980), but without denting the surface of Old Norse narrato- logy,1 both the materials and the methods of Labov are highly relevant to the Icelandic sagas and their folk narratives. In this paper Labov has addressed himself to the very contemporary social problem of “senseless violence” in American life, in the hopes of pinning down wherever he can some of the verbal clues to its psychological causes in the story-telling of his white informants - above all, in any of the spoken words between them and their assailants that might have led to blows. Such an approach to violent actions through narrative and dialogue would miss of its mark were the words that led to blows not “loaded”, i.e., possessed of the social or psychological force to make certain things happen under appropriate conditions. Words that “do things” this way are in the category of speech acts,2 and Labov’s paper draws * This paper, of which a lecture version was read to various university audiences in Scandinavia, Germany, and Switzerland during the first three months of 1989, has benefited by many comments and criticisms from fellow Scandinavianists such as John Lindow, Robert Cook, Anne Heinrichs, Donald Tuckwiller, John E. -

History Or Fiction? Truth-Claims and Defensive Narrators in Icelandic Romance-Sagas

History or fiction? Truth-claims and defensive narrators in Icelandic romance-sagas RALPH O’CONNOR University of Aberdeen Straining the bounds of credibility was an activity in which many mediaeval Icelandic saga-authors indulged. In §25 of Göngu-Hrólfs saga, the hero Hrólfr Sturlaugsson wakes up from an enchanted sleep in the back of beyond to find both his feet missing. Somehow he manages to scramble up onto his horse and find his way back to civilisation – in fact, to the very castle where his feet have been secretly preserved by his bride-to-be. Also staying in that castle is a dwarf who happens to be the best healer in the North.1 Hann mælti: ‘… skaltu nú leggjast niðr við eldinn ok baka stúfana.’ Hrólfr gerði svâ; smurði hann þá smyrslunum í sárin, ok setti við fætrna, ok batt við spelkur, ok lèt Hrólf svâ liggja þrjár nætr. Leysti þá af umbönd, ok bað Hrólf upp standa ok reyna sik. Hrólfr gerði svâ; voru honum fætrnir þá svâ hægir ok mjúkir, sem hann hefði á þeim aldri sár verit. ‘He said, … “Now you must lie down by the fire and warm the stumps”. ‘Hrólfr did so. Then he [the dwarf] applied the ointment to the wounds, placed the feet against them, bound them with splints and made Hrólfr lie like that for three nights. Then he removed the bandages and told Hrólfr to stand up and test his strength. Hrólfr did so; his feet were then as efficient and nimble as if they had never been damaged.’2 This is rather hard to believe – but our scepticism has been anticipated by the saga-author. -

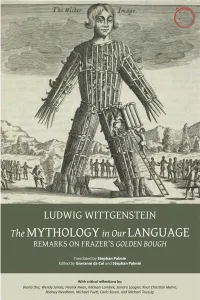

The Mythology in Our Language

THE MYTHOLOGY IN OUR LANGUAGE THE MYTHOLOGY IN OUR LANGUAGE Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough Translated by Stephan Palmié Edited by Giovanni da Col and Stephan Palmié With critical reflections by Veena Das, Wendy James, Heonik Kwon, Michael Lambek, Sandra Laugier, Knut Christian Myhre, Rodney Needham, Michael Puett, Carlo Severi, and Michael Taussig Hau Books Chicago © 2018 Hau Books and Ludwig Wittgenstein, Stephan Palmié, Giovanni da Col, Veena Das, Wendy James, Heonik Kwon, Michael Lambek, Sandra Laugier, Knut Christian Myhre, Rodney Needham, Michael Puett, Carlo Severi, and Michael Taussig Cover: “A wicker man, filled with human sacrifices (071937)” © The British Library Board. C.83.k.2, opposite 105. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Editorial office: Michelle Beckett, Justin Dyer, Sheehan Moore, Faun Rice, and Ian Tuttle Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-1-912808-40-3 LCCN: 2018962822 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is printed, marketed, and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Preface xi chapter 1 Translation is Not Explanation: Remarks on the Intellectual History and Context of Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Frazer 1 Stephan Palmié chapter 2 Remarks on Frazer’s The Golden Bough 29 Ludwig Wittgenstein, translated by Stephan Palmié chapter 3 On Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough 75 Carlo Severi chapter 4 Wittgenstein’s -

1812 GRIMM's FAIRY TALES SNOW-WHITE and ROSE-RED Jacob Ludwig Grimm and Wilhelm Carl Grimm SNOW-WHITE and ROSE-RED

1 1812 GRIMM’S FAIRY TALES SNOW-WHITE AND ROSE-RED Jacob Ludwig Grimm and Wilhelm Carl Grimm Grimm, Jacob (1785-1863) and Wilhelm (1786-1859) - German philologists whose collection “Kinder- und Hausmarchen,” known in English as “Grimm’s Fairy Tales,” is a timeless literary masterpiece. The brothers transcribed these tales directly from folk and fairy stories told to them by common villagers. Snow-White and Rose-Red (1812) - A poor widow and her two kind daughters, Snow-White and Rose-Red, take in a friendly bear who wishes to warm himself. The sisters later help a thankless dwarf who then encounters the bear. SNOW-WHITE AND ROSE-RED THERE WAS once a poor widow who lived in a lonely cottage. In front of the cottage was a garden wherein stood two rose trees, one of which bore white and the other red roses. She had two children who were like the two rose trees, and one was called Snow-white, and the other Rose-red. They were as good and happy, as busy and cheerful as ever two children in the world were, only Snowwhite was more quiet and gentle than Rose-red. Rose-red liked better to run about in the meadows and fields seeking flowers and catching butterflies; but Snowwhite sat at home with her mother, and helped her with her house-work, or read to her when there was nothing to do. The two children were so fond of each other that they always held each other by the hand when they went out together, and when Snow-white said, “We will not leave each other,” Rose-red answered, “Never so long as we live,” and their mother would add, “What one has she must share with the other.” They often ran about the forest alone and gathered red berries, and no beasts did them any harm, but came close to them trustfully. -

Individuals, Communities, and Peacemaking in the Íslendingasögur

(Not) Everything Ends in Tears: Individuals, Communities, and Peacemaking in the Íslendingasögur by Kyle Hughes, B.A., M.Phil PhD Diss. School of English Trinity College Dublin Supervisor: Dr. Helen Conrad O'Briain Submitted to Trinity College Dublin, the University of Dublin March 2017 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the Library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. Name_____________________________________________ Date_____________________________________________ i Summary The íslendingasögur, or Icelandic family sagas, represent a deeply introspective cultural endeavour, the exploration of a nation of strong-willed, independent, and occasionally destructive men and women as they attempted to navigate their complex society in the face of uncertainty and hardship. In a society initially devoid of central authority, the Commonwealth's ability to not only survive, but adapt over nearly four centuries, fascinated the sagamen and their audiences as much as it fascinates scholars and readers today. Focused on feud, its utility in preserving overall order balanced against its destructive potential, the íslendingasögur raise and explore difficult questions regarding the relationship between individual and community, and of power and compromise. This study begins by considering the realities of law and arbitration within the independent Commonwealth, in the context of the intense competitive pressure among goðar and large farmers both during the Commonwealth period and in the early days of Norwegian rule. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

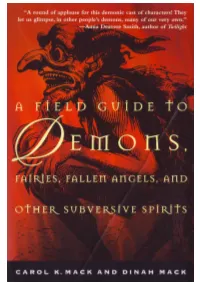

A-Field-Guide-To-Demons-By-Carol-K

A FIELD GUIDE TO DEMONS, FAIRIES, FALLEN ANGELS, AND OTHER SUBVERSIVE SPIRITS A FIELD GUIDE TO DEMONS, FAIRIES, FALLEN ANGELS, AND OTHER SUBVERSIVE SPIRITS CAROL K. MACK AND DINAH MACK AN OWL BOOK HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY NEW YORK Owl Books Henry Holt and Company, LLC Publishers since 1866 175 Fifth Avenue New York, New York 10010 www.henryholt.com An Owl Book® and ® are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC. Copyright © 1998 by Carol K. Mack and Dinah Mack All rights reserved. Distributed in Canada by H. B. Fenn and Company Ltd. Library of Congress-in-Publication Data Mack, Carol K. A field guide to demons, fairies, fallen angels, and other subversive spirits / Carol K. Mack and Dinah Mack—1st Owl books ed. p. cm. "An Owl book." Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8050-6270-0 ISBN-10: 0-8050-6270-X 1. Demonology. 2. Fairies. I. Mack, Dinah. II. Title. BF1531.M26 1998 99-20481 133.4'2—dc21 CIP Henry Holt books are available for special promotions and premiums. For details contact: Director, Special Markets. First published in hardcover in 1998 by Arcade Publishing, Inc., New York First Owl Books Edition 1999 Designed by Sean McDonald Printed in the United States of America 13 15 17 18 16 14 This book is dedicated to Eliza, may she always be surrounded by love, joy and compassion, the demon vanquishers. Willingly I too say, Hail! to the unknown awful powers which transcend the ken of the understanding. And the attraction which this topic has had for me and which induces me to unfold its parts before you is precisely because I think the numberless forms in which this superstition has reappeared in every time and in every people indicates the inextinguish- ableness of wonder in man; betrays his conviction that behind all your explanations is a vast and potent and living Nature, inexhaustible and sublime, which you cannot explain. -

Frau Gothel As a Non-Villainous Mother-Figure," Ellipsis: Vol

Ellipsis Volume 42 Article 24 2015 The Motherly Sorceress: Frau Gothel as a Non-Villainous Mother- Figure Jessica D'Aquin University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/ellipsis Recommended Citation D'Aquin, Jessica (2015) "The Motherly Sorceress: Frau Gothel as a Non-Villainous Mother-Figure," Ellipsis: Vol. 42 , Article 24. DOI: https://doi.org/10.46428/ejail.42.24 Available at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/ellipsis/vol42/iss1/24 This Literary Criticism is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English and Foreign Languages at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ellipsis by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Motherly Sorceress: Frau Gothel as a Non-Villainous Mother-Figure Jessica D ’Aquin Catherine Barragy Mackin Memorial Prize Winner When Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm first published the story of “Rapunzel” in 1812 within their collection Kinder- und Hausmärchen , Frau Gothel, the woman we now know to be the witch who locks Rapunzel in the tower, was originally written using the German word for “fairy.” A few years later, when Wilhelm Grimm heavily edited the tales for stylistic continuity and censoring, Frau Gothel was instead described with the German word for sorceress: “Zauberin.” This word and its connotations are very different from “Hexe,” the German word for witch. Despite the fact that the Grimms never claimed she was a witch, translations into English referred to Frau Gothel as a witch rather than a sorceress, perhaps in an attempt to cast her in a more negative light than the Grimms seemed willing to use. -

Kinsella Feb 13

MORPHEUS: A BILDUNGSROMAN A PARTIALLY BACK-ENGINEERED AND RECONSTRUCTED NOVEL MORPHEUS: A BILDUNGSROMAN A PARTIALLY BACK-ENGINEERED AND RECONSTRUCTED NOVEL JOHN KINSELLA B L A Z E V O X [ B O O K S ] Buffalo, New York Morpheus: a Bildungsroman by John Kinsella Copyright © 2013 Published by BlazeVOX [books] All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the publisher’s written permission, except for brief quotations in reviews. Printed in the United States of America Interior design and typesetting by Geoffrey Gatza First Edition ISBN: 978-1-60964-125-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2012950114 BlazeVOX [books] 131 Euclid Ave Kenmore, NY 14217 [email protected] publisher of weird little books BlazeVOX [ books ] blazevox.org 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 B l a z e V O X trip, trip to a dream dragon hide your wings in a ghost tower sails crackling at ev’ry plate we break cracked by scattered needles from Syd Barrett’s “Octopus” Table of Contents Introduction: Forging the Unimaginable: The Paradoxes of Morpheus by Nicholas Birns ........................................................ 11 Author’s Preface to Morpheus: a Bildungsroman ...................................................... 19 Pre-Paradigm .................................................................................................. 27 from Metamorphosis Book XI (lines 592-676); Ovid ......................................... 31 Building, Night ......................................................................................................