Éva Merenics WHOSE CHILDREN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Documenting Protestant Missionary Activism During the Armenian Genocide

Philanthropy, Faith, and Influence: Documenting Protestant Missionary Activism during the Armenian Genocide Elizabeth N. Call and Matthew Baker, Columbia University Author Note: Elizabeth N. Call, Public Services Librarian, The Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary, Columbia University in the City of New York; Matthew Baker, Collection Services Librarian, The Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary, Columbia University in the City of New York. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Elizabeth Call The Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary 3041 Broadway New York, NY 10027 Contact: [email protected] Philanthropy, Faith, and Influence | The Reading Room | Volume 1, Issue 1 7 Abstract American Protestant missionaries played important political and cultural roles in the late Ottoman Empire in the period before, during, and after the Armenian genocide. They reported on events as they unfolded and were instrumental coordinating and executing relief efforts by Western governments and charities. The Burke Library’s Missionary Research Library, along with several other important collections at Columbia and other nearby research repositories, holds a uniquely rich and comprehensive body of primary and secondary source materials for understanding the genocide through the lens of the missionaries’ attempts to document and respond to the massacres. Keywords: Armenian genocide, Turkey, missionaries, Near East, WWI, Middle East Christianity Philanthropy, Faith, and Influence | The Reading Room | Volume 1, Issue 1 8 Philanthropy, Faith, and Influence: Documenting Protestant Missionary Activism during the Armenian Genocide Elizabeth N. Call and Matthew Baker, Columbia University April 2015 marks the centenary of the beginning of the Armenian genocide, in which an estimated 1 to 1.5 million members of the indigenous and ancient Christian minority in what is now eastern Turkey, along with many co-religionists from the Assyrian and Greek Orthodox communities, perished through forced deportation or execution (Kevorkian, 2011). -

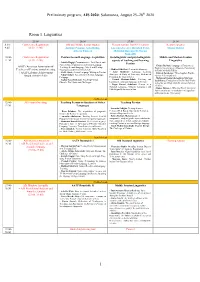

Preliminary Program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28Th 2020

Preliminary program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28th 2020 Room 1. Linguistics 25.08 26.08 27.08 28.08 8:30- Conference Registration Old and Middle Iranian studies Plenary session: Iran-EU relations Keynote speaker 9:45 (8:30–12:00) Antonio Panaino, Götz König, Luciano Zaccara, Rouzbeh Parsi, Maziar Bahari Alberto Cantera Mehrdad Boroujerdi, Narges Bajaoghli 10:00- Conference Registration Persian Second Language Acquisition Sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic Middle and Modern Iranian 11:30 (8:30–12:00) aspects of teaching and learning Linguistics - Latifeh Hagigi: Communicative, Task-Based, and Persian Content-Based Approaches to Persian Language - Chiara Barbati: Language of Paratexts as AATP (American Association of Teaching: Second Language, Mixed and Heritage Tool for Investigating a Monastic Community - Mahbod Ghaffari: Persian Interlanguage Teachers of Persian) annual meeting Classrooms at the University Level in Early Medieval Turfan - Azita Mokhtari: Language Learning + AATP Lifetime Achievement - Ali R. Abasi: Second Language Writing in Persian - Zohreh Zarshenas: Three Sogdian Words ( Strategies: A Study of University Students of (m and ryżי k .kי rγsי β יי Nahal Akbari: Assessment in Persian Language - Award (10:00–13:00) Persian in the United States Pedagogy - Mahmoud Jaafari-Dehaghi & Maryam - Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi: Teaching and - Asghar Seyed-Ghorab: Teaching Persian Izadi Parsa: Evaluation of the Prefixed Verbs learning the formulaic language in Persian Ghazals: The Merits and Challenges in the Ma’ani Kitab Allah Ta’ala -

Book Chapter

Book Chapter Ravished Armenia (1919): Bearing witness in the age of mechanical reproduction. Some thoughts on a film-ordeal GARIBIAN, Sévane Abstract "Ravished Armenia, also entitled Auction of Souls, is the only film of its kind, being based on the testimony of the young Aurora Mardiganian (real name Archaluys Mardigian), who survived the Armenian genocide and exiled in the United States on 1917, aged sixteen. This 1919 silent film is based on a script written by the editors of Aurora’s memoirs. Produced by a pioneer of American cinema, on behalf of the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, it was shot in record time and featured a star cast, Hollywood sets and hundreds of extras. At the top of the bill was Aurora herself. Initially presented as a cinematografic work with a charitable objective, Ravished Armenia was above all a blockbuster, designed to create a commercial sensation amidst which the original witness, dispossessed of her own story, would be lost. The few remaining images/traces (only one reel, as the others had misteriously disappeared) of what was the first cinematografic reconstitution of a genocide narrated by a female survivor testify in themselves to two things: both to the Catastrophe, through the screening of the body-as-witness in [...] Reference GARIBIAN, Sévane. Ravished Armenia (1919): Bearing witness in the age of mechanical reproduction. Some thoughts on a film-ordeal. In: Chabot, Joceline ; Godin, Richard ; Kappler, Stefanie ; Kasparian, Sylvia. Mass Media and the Genocide of the Armenians : One Hundred Years of Uncertain Representation. Basingstoke : Palgrave Mcmillan, 2015. p. 36-50 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:77313 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. -

Missions, Charity, and Humanitarian Action in the Levant (19Th–20Th Century) 21 Chantal Verdeil

Christian Missions and Humanitarianism in the Middle East, 1850–1950 Leiden Studies in Islam and Society Editors Léon Buskens (Leiden University) Nathal M. Dessing (Leiden University) Petra M. Sijpesteijn (Leiden University) Editorial Board Maurits Berger (Leiden University) – R. Michael Feener (Oxford University) – Nico Kaptein (Leiden University) Jan Michiel Otto (Leiden University) – David S. Powers (Cornell University) volume 11 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/lsis Christian Missions and Humanitarianism in the Middle East, 1850–1950 Ideologies, Rhetoric, and Practices Edited by Inger Marie Okkenhaug Karène Sanchez Summerer LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: “Les Capucins français en Syrie. Secours aux indigents”. Postcard, Collection Gélébart (private collection), interwar period. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Okkenhaug, Inger Marie, editor. | Sanchez Summerer, Karène, editor. Title: Christian missions and humanitarianism in the Middle East, 1850-1950 : ideologies, rhetoric, and practices / edited by Inger Marie Okkenhaug, Karène Sanchez Summerer. Other titles: Leiden studies in Islam and society ; v. 11. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. -

NEAR EAST FOUNDATION Annual Report 2014

NEAR EAST FOUNDATION Annual Report 2014 BOARD OF DIRECTORS HONORARY BOARD Shant Mardirossian, Chair Shahnaz Batmanghelid Johnson Garrett, Vice Chair Amir Ali Farman-Farma, Ph.D. Haig Mardikian, Secretary John Goelet Charles Benjamin, Ph.D., President John Grammer Mehrzad Boroujerdi, Ph.D. Ronald Miller Mona Eraiba David Mize Alexander Ghiso Abe Moses Jeff Habib Richard Robarts Linda K. Jacobs, Ph.D. Anthony Williams Amr Nosseir Tarek Younes Matthew Quigley Soroush Shehabi PRESIDENT’S COUNCIL Robert Solomon William Sullivan H.E. Andre Azoulay Harris Williams Ian Bremmer Ambassador Edward P. Djerejian Vartan Gregorian, Ph.D. ACADEMIC COUNCIL Ambassador Richard W. Murphy John Kerr, Ph.D. Her Majesty Queen Noor of Jordan John McPeak, Ph.D. James Steinberg Thomas Mullins Ambassador Frank G. Wisner Juliet Sorensen, J.D. Michaela Walsh On the Cover: Schoolgirls in Morocco’s High Atlas Mountains. NEAR EAST FOUNDATION Annual Report 2014 Near East Foundation at 100: Celebrating the Past, Shaping the Future Near East Relief orphans at Antylas - lesson on the beach, c. 1920s. This year marks the 100th anniversary volunteered to go to the region to offer of the founding of Near East Relief, as food, medical care, and educational and Near East Relief Historical the Near East Foundation was known vocational training for adults and children. Society originally, which was created in 1915 This heroic effort marked the first great In 2014, NEF created the Near East to help rescue an estimated 1.5 million outpouring of American humanitarian Relief Historical Society to raise Armenian refugees and orphans after the assistance—giving birth to citizen awareness about this important collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the philanthropy, a movement that embodies chapter in American history. -

History Stands to Repeat Itself As Armenia Renews Ties to Asia

THE ARMENIAN GENEALOGY MOVEMENT P.38 ARMENIAN GENERAL BENEVOLENT UNION AUG. 2019 History stands to repeat itself as Armenia renews ties to Asia Armenian General Benevolent Union ESTABLISHED IN 1906 Հայկական Բարեգործական Ընդհանուր Միութիւն Central Board of Directors President Mission Berge Setrakian To promote the prosperity and well-being of all Armenians through educational, Honorary Member cultural, humanitarian, and social and economic development programs, projects His Holiness Karekin II, and initiatives. Catholicos of All Armenians Annual International Budget Members USD UNITED STATES Forty-six million dollars ( ) Haig Ariyan Education Yervant Demirjian 24 primary, secondary, preparatory and Saturday schools; scholarships; alternative Eric Esrailian educational resources (apps, e-books, AGBU WebTalks and more); American Nazareth A. Festekjian University of Armenia (AUA); AUA Extension-AGBU Artsakh Program; Armenian Arda Haratunian Virtual College (AVC); TUMO x AGBU Sarkis Jebejian Ari Libarikian Cultural, Humanitarian and Religious Ani Manoukian AGBU News Magazine; the AGBU Humanitarian Emergency Relief Fund for Syrian Lori Muncherian Armenians; athletics; camps; choral groups; concerts; dance; films; lectures; library research Levon Nazarian centers; medical centers; mentorships; music competitions; publications; radio; scouts; Yervant Zorian summer internships; theater; youth trips to Armenia. Armenia: Holy Etchmiadzin; AGBU ARMENIA Children’s Centers (Arapkir, Malatya, Nork), and Senior Dining Centers; Hye Geen Vasken Yacoubian -

The Armenian Genocide and the Making of Modern Humanitarian Media in the US, 1915-1925

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 "Lest They Perish": The Armenian Genocide and the Making of Modern Humanitarian Media in the U.S., 1915-1925 Jaffa Panken University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Panken, Jaffa, ""Lest They Perish": The Armenian Genocide and the Making of Modern Humanitarian Media in the U.S., 1915-1925" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1396. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1396 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1396 For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Lest They Perish": The Armenian Genocide and the Making of Modern Humanitarian Media in the U.S., 1915-1925 Abstract Between celebrity spokesmen and late night informercials, international humanitarian aid organizations use multiple media strategies to generate public interest in their programs. Though this humanitarian media has seemingly proliferated in the past thirty years, these publicity campaigns are no recent phenomenon but one that emerged from the World War I era. "Lest They Perish" is a case study of the modernization of international humanitarian media in the U.S. during and after the Armenian genocide from 1915 to 1925. This study concerns the Near East Relief, an international humanitarian organization that raised and contributed over $100,000,000 in aid to the Armenians during these years of violence. As war raged throughout Europe and Western Asia, American governmental propagandists kept the public invested in the action overseas. Private philanthropies were using similar techniques aimed at enveloping prospective donors in "whirlwind campaigns" to raise funds. -

That Jazz Is a Risky Choice As a Career, and Is Constantly Reevaluating Her Goals for the Present, Near Future, and the Long Run

DECEMBER 5, 2015 Mirror-SpeTHE ARMENIAN ctator Volume LXXXVI, NO. 21, Issue 4415 $ 2.00 NEWS INBRIEF The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 Hayastan All-Armenian Armenia’s President Attends Paris Climate Summit Fund’s 18th Telethon PARIS (Public Radio members suggesting Raised $10,378,465 of Armenia) — On that it should not be Monday, November 30, simply about good YEREVAN — Hayastan All-Armenian Fund’s world- President Serge intentions but clear-cut wide Telethon 2015 raised $10,378,465 in pledges Sargisian participated at and strong political mes- and donations. The amounts raised at the telethon, the 21st Conference of sages to ensure that safe with the theme “Our Home,” will be used to con- the Parties to the United future of the humanity struct single-family homes for families in Nagorno Nations Framework has no alternative. Karabagh who have five or more children and lack Convention on Climate During his speech, adequate housing, as well as to implement special Change. The conference, Sargisian stressed that projects adopted by the benefactors. which is presided over by climate change threat- Toward the realization of the projects, the worldwide France, is being attended ens all states equally, affiliates of the fund have been carrying out a multitude by the heads of state and regardless of their size of public-awareness and fundraising campaigns during representatives from 150 or level of development. the year, including phone-a-thons, radio-thons, a charity countries and by thou- Even though Armenia’s concert and fundraising dinners. sands of delegates. -

Supervisor, Facilitator and Arbitrator: UNIVERSITY of OSLO

Supervisor, Facilitator and Arbitrator: a Study of the Involvement of the Minority Section of the League of Nations in the Forced Population Exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923 Mads Drange Master’s Thesis in History Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History (IAKH) UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2017 II Supervisor, Facilitator and Arbitrator: a Study of the Involvement of the Minority Section of the League of Nations in the Forced Population Exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923 III Copyright: Mads Drange 2017 Supervisor, Facilitator and Arbitrator: a Study of the Involvement of the Minority Section of the League of Nations in the Forced Population Exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923 www.duo.uio.no Printing: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Summary In January 1923 in the Swiss town of Lausanne, Turkey and Greece agreed to a forced population exchange involving more than 1.4 million people. According to the agreement, all Turkish nationals of the Greek Orthodox religion, and all Greek nationals of the Muslim religion, were supposed to move, resettling in Greece and Turkey respectively. The agreement had come into being as part of the negotiations between the new Turkish republic and the Allied nations after the Greco-Turkish war and it represented a pragmatic attempt to solve the refugee crisis in the region at the time. To ensure that the exchange was executed in accordance with the provisions of the agreement, a Mixed Commission was established consisting of Greek, Turkish and neutral members. The neutral members were appointed by the League of Nations’ Council. This thesis studies the role of the League of Nations in the execution of the Greco- Turkish population exchange. -

Giragn0rya3 :Yr;Ig

St. John Armenian Church of Greater Detroit 22001 Northwestern Highway | Southfield, MI 48075 248.569.3405 (phone) | 248.569.0716 (fax) www.stjohnsarmenianchurch.org The Very Reverend Father Aren Jebejian, Pastor The Reverend Father Armash Bagdasarian, Assistant Pastor Clergy residing within the St. John parish and community: The Reverend Father Diran Papazian The Reverend Father Garabed Kochakian The Reverend Father Abraham Ohanesian Deacon Rubik Mailian, Director of Sacred Music and Pastoral Assistant Ms. Margaret Lafian, Organist Giragn0rya3 :yr;ig Welcome! We welcome you to the Divine Liturgy/Soorp Badarak and invite all who are Baptized and Chris- mated in, or are in communion with, the Armenian Church to receive the Sacrament of Holy Commun- ion. If you are new to our parish and would like information about our many parish groups, please ask any Parish Council member on duty at the lobby desk. Make certain you fill out a contact card before you leave so we can be in touch. Enter to worship the Lord Jesus Christ who loves you and depart with His love to serve others. 2018 THIRD SUNDAY AFTER THE OCTAVE OF THEOPHANY THE LORD’S DAY - SCHEDULE OF WORSHIP Morning Service / Առաւօտեան Ժամերգութիւն…9:00 am Divine Liturgy / Ս.Պատարագ …………………………...9:45 am SACRED LECTIONS OF THE LITURGY Isaiah 63:7-18, II Timothy 3:1-12, John 6:22-38 Lector: STEVEN HAGOPIAN Today, Fr. Aren is delivering the Children’s Sermon. Poon Paregentan In the directive given by His Eminence Archbishop Khajag Barsamian, Primate, Badarak on Sunday, February 11th, will be a closed Badarak. -

Near East Relief and the Armenian Crisis, 1915-1930

America’s Sacred Duty: Near East Relief and the Armenian Crisis, 1915-1930 By Sarah Miglio Ph.D. Candidate, Department of History University of Notre Dame 219 O‟Shaughnessy Hall Notre Dame, Indiana 46614 [email protected] © 2009 by Sarah Miglio Editor's Note: This research report is presented here with the author‟s permission but should not be cited or quoted without the author‟s consent. Rockefeller Archive Center Research Reports Online is a periodic publication of the Rockefeller Archive Center. Edited by Ken Rose and Erwin Levold. Research Reports Online is intended to foster the network of scholarship in the history of philanthropy and to highlight the diverse range of materials and subjects covered in the collections at the Rockefeller Archive Center. The reports are drawn from essays submitted by researchers who have visited the Archive Center, many of whom have received grants from the Archive Center to support their research. The ideas and opinions expressed in this report are those of the author and are not intended to represent the Rockefeller Archive Center. Throughout World War I and its aftermath, hundreds of thousands of refugees across Europe and Asia Minor were the recipients of humanitarian aid. But in the United States one ethnic group in particular, the Armenians, captured Americans‟ imaginations and prompted the nation to action. Americans worried that Armenians were targeted for extinction, so U.S. cultural and political elites took up this humanitarian cause in the name of their “Christian” citizenship. This was more than relief work in the name of modern goodwill – it was a rescue mission undertaken with solemn vows of the American Christian‟s duty to protect the poor, starving Armenians. -

Armenian National Committee of America | Western Region 104 N

Armenian National Committee of America | Western Region 104 N. Belmont St., Suite 200, Glendale, CA 91206 | 818.500.1918 | [email protected] ancawr.org | Facebook.com/ANCAWesternRegion | IG and Twitter: ANCA_WR For Additional Information Contact Armenian National Committee of America – Western Region 104 N. Belmont St., Suite 200, Glendale, CA 91206 818.500.1918 | [email protected] | ancawr.org Table of Contents The Armenian Genocide ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 Timeline of Events ................................................................................................................................................................... 2 US Response and Connection to the Armenian Genocide ...................................................................................................... 4 Demands of the Armenian-American Community for the Armenian Genocide ........................................................................ 5 Republic of Artsakh ................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Demands of the Armenian-American Community for Artsakh.................................................................................................. 8 About: The Armenian National Committee of America – Western Region ..........................................................................