Promoting Natural Resource Conflict Management in an Illiberal Setting: Experiences from Central Darfur, Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

CRS Report for Congress Received Through the CRS Web

Order Code RS2 1973 November 16 2004 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Al Qaeda Statements and Evolving Ideology Christopher Blanchard Analyst in Middle Eastern Affairs Foreign Affairs Defense and Trade Division Summary The release ofa new videotape by Osama Bin Laden in late October 2004 rekindled public debate surrounding Al Qaedas ideology motives and future plans to attack the United States The highly political tone and content of the two most recent statements released by Osama Bin Laden and October 2004 have led some terrorism analysts to speculate that the messages may signal new attempt by Bin Laden to create lasting political leadership role for himself and Al Qaeda as the vanguard of an international Islamist ideological movement Others have argued that Al Qaedas presently limited capabilities have inspired temporary rhetorical shift and that the groups primary goal remains carrying out terrorist attacks against the United States and its allies around the world with particular emphasis on targeting economic infrastructure and fomenting unrest in fraq and Afghanistan This report reviews Osama Bin Ladens use of public statements from the mid-1990s to the present and analyzes the evolving ideological and political content of those statements The report will be updated periodically For background on the Al Qaeda terrorist network see CRS Report R52 1529 Al Qaeda after the Iraq Conflict Al Qaedas Media Campaign Osama Bin Laden and the Al Qaeda terrorist network have conducted sophisticated public relations and -

Peace, Propaganda, and the Promised Land

1 MEDIA EDUCATION F O U N D A T I O N 60 Masonic St. Northampton, MA 01060 | TEL 800.897.0089 | [email protected] | www.mediaed.org Peace, Propaganda & the Promised Land U.S. Media & the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Transcript (News clips) Narrator: The Israeli-Palestinian conflict dominates American news coverage of International issues. Given the news coverage is America's main source of information on the conflict, it becomes important to examine the stories the news media are telling us, and to ask the question, Does the news reflect the reality on the ground? (News clips) Prof. Noam Chomsky: The West Bank and the Gaza strip are under a military occupation. It's the longest military occupation in modern history. It's entering its 35th year. It's a harsh and brutal military occupation. It's extremely violent. All the time. Life is being made unlivable by the population. Gila Svirsky: We have what is now quite an oppressive regime in the occupied territories. Israeli's are lording it over Palestinians, usurping their territory, demolishing their homes, exerting a very severe form of military rule in order to remain there. And on the other hand, Palestinians are lashing back trying to throw off the yoke of oppression from the Israelis. Alisa Solomon: I spent a day traveling around Gaza with a man named Jabra Washa, who's from the Palestinian Center for Human Rights and he described the situation as complete economic and social suffocation. There's no economy, the unemployment is over 60% now. Crops can't move. -

NEEDLESS DEATHS in the GULF WAR Civilian Casualties During The

NEEDLESS DEATHS IN THE GULF WAR Civilian Casualties During the Air Campaign and Violations of the Laws of War A Middle East Watch Report Human Rights Watch New York $$$ Washington $$$ Los Angeles $$$ London Copyright 8 November 1991 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Cover design by Patti Lacobee Watch Committee Middle East Watch was established in 1989 to establish and promote observance of internationally recognized human rights in the Middle East. The chair of Middle East Watch is Gary Sick and the vice chairs are Lisa Anderson and Bruce Rabb. Andrew Whitley is the executive director; Eric Goldstein is the research director; Virginia N. Sherry is the associate director; Aziz Abu Hamad is the senior researcher; John V. White is an Orville Schell Fellow; and Christina Derry is the associate. Needless deaths in the Gulf War: civilian casualties during the air campaign and violations of the laws of war. p. cm -- (A Middle East Watch report) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-56432-029-4 1. Persian Gulf War, 1991--United States. 2. Persian Gulf War, 1991-- Atrocities. 3. War victims--Iraq. 4. War--Protection of civilians. I. Human Rights Watch (Organization) II. Series. DS79.72.N44 1991 956.704'3--dc20 91-37902 CIP Human Rights Watch Human Rights Watch is composed of Africa Watch, Americas Watch, Asia Watch, Helsinki Watch, Middle East Watch and the Fund for Free Expression. The executive committee comprises Robert L. Bernstein, chair; Adrian DeWind, vice chair; Roland Algrant, Lisa Anderson, Peter Bell, Alice Brown, William Carmichael, Dorothy Cullman, Irene Diamond, Jonathan Fanton, Jack Greenberg, Alice H. -

Laura Jarboe

ABSTRACT REAGAN’S ANTITERRORISM: THE ROLE OF LEBANON by Laura Jarboe In the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan was faced with an increase in terrorism directed specifically at the United States. He feared that terrorism compromised America’s reputation, especially in the midst of the Cold War. An examination of terrorism which specifically targeted the military reveals that Reagan’s language and proposed policies emulated his Cold War fight. By 1985, the Reagan administration developed a Task Force for combating terrorism. Close investigation of the Task Force’s publication reveals that although Reagan talked a hard-line against terrorists, he partook in little action against them. REAGAN’S ANTITERRORISM: THE ROLE OF LEBANON A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by Laura E. Jarboe Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2012 Advisor______________________________ Amanda McVety Reader_______________________________ Sheldon Anderson Reader_______________________________ Matthew Gordon Table of Contents Preface …………………………………………………………………………………………....1 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………2 A New Terrorism is Born ………………………………………………………………………...5 Reagan Reacts to Terrorism ……………………………………………………………………..12 Calming the Public ...................................................................................................................... 166 The White House Investigates ................................................................................................... -

Documenting Protestant Missionary Activism During the Armenian Genocide

Philanthropy, Faith, and Influence: Documenting Protestant Missionary Activism during the Armenian Genocide Elizabeth N. Call and Matthew Baker, Columbia University Author Note: Elizabeth N. Call, Public Services Librarian, The Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary, Columbia University in the City of New York; Matthew Baker, Collection Services Librarian, The Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary, Columbia University in the City of New York. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Elizabeth Call The Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary 3041 Broadway New York, NY 10027 Contact: [email protected] Philanthropy, Faith, and Influence | The Reading Room | Volume 1, Issue 1 7 Abstract American Protestant missionaries played important political and cultural roles in the late Ottoman Empire in the period before, during, and after the Armenian genocide. They reported on events as they unfolded and were instrumental coordinating and executing relief efforts by Western governments and charities. The Burke Library’s Missionary Research Library, along with several other important collections at Columbia and other nearby research repositories, holds a uniquely rich and comprehensive body of primary and secondary source materials for understanding the genocide through the lens of the missionaries’ attempts to document and respond to the massacres. Keywords: Armenian genocide, Turkey, missionaries, Near East, WWI, Middle East Christianity Philanthropy, Faith, and Influence | The Reading Room | Volume 1, Issue 1 8 Philanthropy, Faith, and Influence: Documenting Protestant Missionary Activism during the Armenian Genocide Elizabeth N. Call and Matthew Baker, Columbia University April 2015 marks the centenary of the beginning of the Armenian genocide, in which an estimated 1 to 1.5 million members of the indigenous and ancient Christian minority in what is now eastern Turkey, along with many co-religionists from the Assyrian and Greek Orthodox communities, perished through forced deportation or execution (Kevorkian, 2011). -

The Obama/Pentagon War Narrative, the Real War and Where Afghan Civilian Deaths Do Matter Revista De Paz Y Conflictos, Núm

Revista de Paz y Conflictos E-ISSN: 1988-7221 [email protected] Universidad de Granada España Herold, Marc W. The Obama/Pentagon War Narrative, the Real War and Where Afghan Civilian Deaths Do Matter Revista de Paz y Conflictos, núm. 5, 2012, pp. 44-65 Universidad de Granada Granada, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=205024400003 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative issn: 1988-7221 The Obama/Pentagon War Narrative, the Real War and Where Afghan Civilian Deaths Do Matter El relato bélico de Obama y del Pentágono, la verdadera guerra y dónde importan realmente las número 5 año 2012 número muertes de los civiles afganos Recibido: 01/03/2011 Marc W. Herold Aceptado: 31/10/2011 [email protected] Profesor de Desarrollo Económico Universidad de New Hampshire en Durham (New Hampshire, EE.UU.) Abstract This essay explores upon two inter-related issues: (1) the course of America’s raging Afghan war as actually experienced on the ground as contrasted with the Pentagon and mainstream media narrative and (2) the unrelenting Obama/Pentagon efforts to control the public narrative of that war.1 As the real war on the ground spread geographically and violence intensified, U.S. efforts to construct a positive spin re-doubled. An examination of bodies – of foreign occupa- tion forces and innocent Afghan civilians – reveals a clear trade-off. -

Why They Died Civilian Casualties in Lebanon During the 2006 War

September 2007 Volume 19, No. 5(E) Why They Died Civilian Casualties in Lebanon during the 2006 War Map: Administrative Divisions of Lebanon .............................................................................1 Map: Southern Lebanon ....................................................................................................... 2 Map: Northern Lebanon ........................................................................................................ 3 I. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................... 4 Israeli Policies Contributing to the Civilian Death Toll ....................................................... 6 Hezbollah Conduct During the War .................................................................................. 14 Summary of Methodology and Errors Corrected ............................................................... 17 II. Recommendations........................................................................................................ 20 III. Methodology................................................................................................................ 23 IV. Legal Standards Applicable to the Conflict......................................................................31 A. Applicable International Law ....................................................................................... 31 B. Protections for Civilians and Civilian Objects ...............................................................33 -

The War on Lebanon “I Put This Together to Help Me Come to Terms with What Has Just Happened to My Country”

The war on Lebanon “I put this together to help me come to terms with what has just happened to my country” 2 The war on Lebanon Post mortem Wednesday 12th July Assault Destruction Suffering Humanitarian crisis Economic ruin Ecological disaster War crimes Stench of politics Unity Fragile Ceasefire Aftermath Additional information 3 Post Mortem 12 July – 14 August 2006 The cost The scale Israel Lebanon Civilian dead 43 1,130 Civilian 650 3,697 wounded Military dead 116 55* Displaced 500,000 915,000 6,900 homes** 900 businesses Damage 300 buildings 145 bridges 29 utilities Economic $1.5bn $6.5bn*** Bombed 4,000 100,000**** Source: Figures and map from BBC News *Israel estimates 550 ** Lebanese government estimates 15,000 *** Lebanese Council for Development and Reconstruction 4bn estimated reconstruction + 2.5bn earnings loss at 8% GDP **** Estimate based on UN figures of 3,000 attacks per day: http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2006/iha1220.doc.htm4 A skirmish between Hezbollah and Israel escalates into war Wednesday 12th July Hezbollah fires rockets into Israel and raids an army post on the border. Three Israeli soldiers are killed and two are captured. Israel sends a tank into Lebanon in pursuit. The tank is destroyed. Five Israeli soldiers are killed. "It is an act of war by the state of Lebanon against the state of Israel in its sovereign territory.” (Ehud Olmert, Israeli Prime Minister) “The government was not aware of, and does not take responsibility for, nor endorses, what happened on the international border." (Fouad Siniora, Lebanese Prime Minister) “No military operation will return the Israeli captured soldiers. -

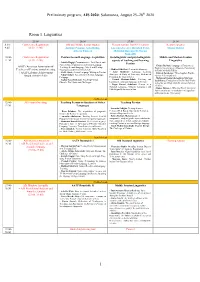

Preliminary Program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28Th 2020

Preliminary program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28th 2020 Room 1. Linguistics 25.08 26.08 27.08 28.08 8:30- Conference Registration Old and Middle Iranian studies Plenary session: Iran-EU relations Keynote speaker 9:45 (8:30–12:00) Antonio Panaino, Götz König, Luciano Zaccara, Rouzbeh Parsi, Maziar Bahari Alberto Cantera Mehrdad Boroujerdi, Narges Bajaoghli 10:00- Conference Registration Persian Second Language Acquisition Sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic Middle and Modern Iranian 11:30 (8:30–12:00) aspects of teaching and learning Linguistics - Latifeh Hagigi: Communicative, Task-Based, and Persian Content-Based Approaches to Persian Language - Chiara Barbati: Language of Paratexts as AATP (American Association of Teaching: Second Language, Mixed and Heritage Tool for Investigating a Monastic Community - Mahbod Ghaffari: Persian Interlanguage Teachers of Persian) annual meeting Classrooms at the University Level in Early Medieval Turfan - Azita Mokhtari: Language Learning + AATP Lifetime Achievement - Ali R. Abasi: Second Language Writing in Persian - Zohreh Zarshenas: Three Sogdian Words ( Strategies: A Study of University Students of (m and ryżי k .kי rγsי β יי Nahal Akbari: Assessment in Persian Language - Award (10:00–13:00) Persian in the United States Pedagogy - Mahmoud Jaafari-Dehaghi & Maryam - Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi: Teaching and - Asghar Seyed-Ghorab: Teaching Persian Izadi Parsa: Evaluation of the Prefixed Verbs learning the formulaic language in Persian Ghazals: The Merits and Challenges in the Ma’ani Kitab Allah Ta’ala -

Book Chapter

Book Chapter Ravished Armenia (1919): Bearing witness in the age of mechanical reproduction. Some thoughts on a film-ordeal GARIBIAN, Sévane Abstract "Ravished Armenia, also entitled Auction of Souls, is the only film of its kind, being based on the testimony of the young Aurora Mardiganian (real name Archaluys Mardigian), who survived the Armenian genocide and exiled in the United States on 1917, aged sixteen. This 1919 silent film is based on a script written by the editors of Aurora’s memoirs. Produced by a pioneer of American cinema, on behalf of the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, it was shot in record time and featured a star cast, Hollywood sets and hundreds of extras. At the top of the bill was Aurora herself. Initially presented as a cinematografic work with a charitable objective, Ravished Armenia was above all a blockbuster, designed to create a commercial sensation amidst which the original witness, dispossessed of her own story, would be lost. The few remaining images/traces (only one reel, as the others had misteriously disappeared) of what was the first cinematografic reconstitution of a genocide narrated by a female survivor testify in themselves to two things: both to the Catastrophe, through the screening of the body-as-witness in [...] Reference GARIBIAN, Sévane. Ravished Armenia (1919): Bearing witness in the age of mechanical reproduction. Some thoughts on a film-ordeal. In: Chabot, Joceline ; Godin, Richard ; Kappler, Stefanie ; Kasparian, Sylvia. Mass Media and the Genocide of the Armenians : One Hundred Years of Uncertain Representation. Basingstoke : Palgrave Mcmillan, 2015. p. 36-50 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:77313 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. -

Missions, Charity, and Humanitarian Action in the Levant (19Th–20Th Century) 21 Chantal Verdeil

Christian Missions and Humanitarianism in the Middle East, 1850–1950 Leiden Studies in Islam and Society Editors Léon Buskens (Leiden University) Nathal M. Dessing (Leiden University) Petra M. Sijpesteijn (Leiden University) Editorial Board Maurits Berger (Leiden University) – R. Michael Feener (Oxford University) – Nico Kaptein (Leiden University) Jan Michiel Otto (Leiden University) – David S. Powers (Cornell University) volume 11 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/lsis Christian Missions and Humanitarianism in the Middle East, 1850–1950 Ideologies, Rhetoric, and Practices Edited by Inger Marie Okkenhaug Karène Sanchez Summerer LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: “Les Capucins français en Syrie. Secours aux indigents”. Postcard, Collection Gélébart (private collection), interwar period. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Okkenhaug, Inger Marie, editor. | Sanchez Summerer, Karène, editor. Title: Christian missions and humanitarianism in the Middle East, 1850-1950 : ideologies, rhetoric, and practices / edited by Inger Marie Okkenhaug, Karène Sanchez Summerer. Other titles: Leiden studies in Islam and society ; v. 11. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020.