Book Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Book # Ravished Armenia: the Story of Aurora Mardiganian

NHT7XGORXZTT ^ Kindle Ravished Armenia: The Story of Aurora Mardiganian, the Christian Girl, Who Survived... Ravished Armenia: The Story of Aurora Mardiganian, the Christian Girl, Who Survived the Great Massacres Filesize: 2.33 MB Reviews A whole new eBook with a brand new point of view. It is definitely simplistic but shocks in the 50 percent of the publication. I am just pleased to explain how this is the greatest ebook i have read during my very own daily life and could be he best ebook for possibly. (Mitchell Kuhn III) DISCLAIMER | DMCA RNPHNY9VIQO6 « eBook « Ravished Armenia: The Story of Aurora Mardiganian, the Christian Girl, Who Survived... RAVISHED ARMENIA: THE STORY OF AURORA MARDIGANIAN, THE CHRISTIAN GIRL, WHO SURVIVED THE GREAT MASSACRES To save Ravished Armenia: The Story of Aurora Mardiganian, the Christian Girl, Who Survived the Great Massacres eBook, remember to refer to the web link below and save the file or gain access to additional information which are have conjunction with RAVISHED ARMENIA: THE STORY OF AURORA MARDIGANIAN, THE CHRISTIAN GIRL, WHO SURVIVED THE GREAT MASSACRES ebook. Indoeuropeanpublishing.com, United States, 2014. Paperback. Book Condition: New. 228 x 150 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****. Aurora (Arshaluys) Mardiganian (January 12, 1901 - February 6, 1994) was an Armenian American author, actress and a survivor of the Armenian Genocide. Aurora Mardiganian was the daughter of a prosperous Armenian family living in Chmshgatsak twenty miles north of Harput, Ottoman Turkey. Witnessing the deaths of her family members and being forced to march over 1,400 miles, during which she was kidnapped and sold into the slave markets of Anatolia, Mardiganian escaped to Tiflis (modern Tbilisi, Georgia), then to St. -

'A Reign of Terror'

‘A Reign of Terror’ CUP Rule in Diyarbekir Province, 1913-1923 Uğur Ü. Üngör University of Amsterdam, Department of History Master’s thesis ‘Holocaust and Genocide Studies’ June 2005 ‘A Reign of Terror’ CUP Rule in Diyarbekir Province, 1913-1923 Uğur Ü. Üngör University of Amsterdam Department of History Master’s thesis ‘Holocaust and Genocide Studies’ Supervisors: Prof. Johannes Houwink ten Cate, Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies Dr. Karel Berkhoff, Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies June 2005 2 Contents Preface 4 Introduction 6 1 ‘Turkey for the Turks’, 1913-1914 10 1.1 Crises in the Ottoman Empire 10 1.2 ‘Nationalization’ of the population 17 1.3 Diyarbekir province before World War I 21 1.4 Social relations between the groups 26 2 Persecution of Christian communities, 1915 33 2.1 Mobilization and war 33 2.2 The ‘reign of terror’ begins 39 2.3 ‘Burn, destroy, kill’ 48 2.4 Center and periphery 63 2.5 Widening and narrowing scopes of persecution 73 3 Deportations of Kurds and settlement of Muslims, 1916-1917 78 3.1 Deportations of Kurds, 1916 81 3.2 Settlement of Muslims, 1917 92 3.3 The aftermath of the war, 1918 95 3.4 The Kemalists take control, 1919-1923 101 4 Conclusion 110 Bibliography 116 Appendix 1: DH.ŞFR 64/39 130 Appendix 2: DH.ŞFR 87/40 132 Appendix 3: DH.ŞFR 86/45 134 Appendix 4: Family tree of Y.A. 136 Maps 138 3 Preface A little less than two decades ago, in my childhood, I became fascinated with violence, whether it was children bullying each other in school, fathers beating up their daughters for sneaking out on a date, or the omnipresent racism that I did not understand at the time. -

Statement on the Second Global Forum Against the Crime Of

PC.DEL/589/16 29 April 2016 ENGLISH only Statement On the Second Global Forum Against the Crime of Genocide and Aurora Prize Award delivered by Ambassador Arman Kirakossian at the 1098thMeeting of the OSCE Permanent Council April 28, 2016 Mr. Chairman, The Remembrance and Education of Genocide is an important part of the OSCE human dimension commitments and we would like to draw the attention of the Permanent Council to two events, Global forum against Genocide and Aurora prize award ceremony, which were held in Yerevan and got wide international attention and participation in the framework of the Armenian Genocide commemoration. The Second Global Forum on the Crime of Genocide, was held in Yerevan on April 23-24. The statement of the President of the Republic of Armenia at the Forum was distributed in the OSCE. The general heading of this year’s forum was “Living Witnesses of Genocide”. Participation of a number of survivors of genocides and other crimes against humanity in different parts of the world made the conference indeed a remarkable and at the same time inspiring event. Mr. Youk Chhang, survivor of Khmer Rouge terror and currently Executive Director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia, Nadia Murat, survivor of the Genocide of Yezidi people in Iraq, who endured torture and degrading treatment by ISIL Mr. Kabanda Aloys, survivor of Rwanda Genocide and currently the Administrator of the Ibuka Memory and Justice Association along with other participants shared their stories of suffering, struggle, gratitude and revival. The very presence of these people in itself bore the powerful message that genocide perpetrators never win. -

Human Rights: History and Theory Spring 2015, Tuesday-Thursday, 2:30-3:50 P.M., KIJP 215 Dr

PJS 494, Human Rights: History and Theory Spring 2015, Tuesday-Thursday, 2:30-3:50 p.m., KIJP 215 Dr. Everard Meade, Director, Trans-Border Institute Office Hours: Tuesdays, 4-5:30 p.m., or by appointment, KIJP 126 ixty years after the passage of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, there’s widespread agreement over what human rights should be. And yet, what human rights are – where they come from, how best to achieve their promise, S and what they mean to people living through war, atrocity, and poverty – remains more contentious than ever. This course explores where human rights come from and what they mean by integrating them into a history of attempts to alleviate and prevent human suffering and exploitation, from the Conquest of the Americas and the origins of the Enlightenment, through the First World War and the rise of totalitarianism, a period before the widespread use of the term “human rights,” and one that encompasses the early heyday of humanitarianism. Many attempts to alleviate human suffering and exploitation do not articulate a set of rights-based claims, nor are they framed in ways that empower individual victims and survivors, or which set principled precedents to be applied in future cases. Indeed, lumping human rights together with various humanitarian interventions risks watering down the struggle for justice in the face of power at the core of human rights praxis, rendering the concept an empty signifier, a catch-all for “doing good” in the world. On the other hand, the social movements and activists who invest human rights with meaning are often ideologically eclectic, and pursue a mix of principled and strategic actions. -

The Obama Administration and the Struggles to Prevent Atrocities in the Central African Republic

POLICY PAPER November 2016 THE OBAMA ADMINISTRATION AUTHOR: AND THE STRUGGLE TO Charles J. Brown Leonard and Sophie Davis PREVENT ATROCITIES IN THE Genocide Prevention Fellow, January – June 2015. Brown is CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC currently Managing Director of Strategy for Humanity, LLC. DECEMBER 2012 – SEPTEMBER 2014 1 METHODOLOGY AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report is the product of research conducted while I was the Leonard and Sophie Davis Genocide Prevention Fellow at the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide at United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM). It is based on a review of more than 3,500 publicly available documents, including material produced by the US and French governments, the United Nations, the African Union, and the Economic Community of Central African States; press stories; NGO reports; and the Twitter and Facebook accounts of key individuals. I also interviewed a number of current and former US government officials and NGO representatives involved in the US response to the crisis. Almost all interviewees spoke on background in order to encourage a frank discussion of the relevant issues. Their views do not necessarily represent those of the agencies or NGOs for whom they work or worked – or of the United States Government. Although I attempted to meet with as many of the key players as possible, several officials turned down or did not respond to interview requests. I would like to thank USHMM staff, including Cameron Hudson, Naomi Kikoler, Elizabeth White, Lawrence Woocher, and Daniel Solomon, for their encouragement, advice, and comments. Special thanks to Becky Spencer and Mary Mennel, who were kind enough to make a lakeside cabin available for a writing retreat. -

Sabiha Gökçen's 80-Year-Old Secret‖: Kemalist Nation

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO ―Sabiha Gökçen‘s 80-Year-Old Secret‖: Kemalist Nation Formation and the Ottoman Armenians A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Fatma Ulgen Committee in charge: Professor Robert Horwitz, Chair Professor Ivan Evans Professor Gary Fields Professor Daniel Hallin Professor Hasan Kayalı Copyright Fatma Ulgen, 2010 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Fatma Ulgen is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii DEDICATION For my mother and father, without whom there would be no life, no love, no light, and for Hrant Dink (15 September 1954 - 19 January 2007 iv EPIGRAPH ―In the summertime, we would go on the roof…Sit there and look at the stars…You could reach the stars there…Over here, you can‘t.‖ Haydanus Peterson, a survivor of the Armenian Genocide, reminiscing about the old country [Moush, Turkey] in Fresno, California 72 years later. Courtesy of the Zoryan Institute Oral History Archive v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………….... -

Ravished Armenia”

THIS STORY OF AURORA MARDIGANIAN which is the most amazing narrative ever written has been reproduced for the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief in a TREMENDOUS MOTION PICTURE SPECTACLE “RAVISHED ARMENIA” Through which runs the thrilling yet tender romance of this CHRISTIAN GIRL WHO SURVIVED THE GREAT MASSACRES Undoubtedly it is one of the greatest and most elaborate motion pictures of the age — every stirring scene through which Aurora lives in the book, is lived again on the motion picture screen. SEE AURORA, HERSELF, IN HER STORY Scenario by Nora Wain — Staged by Oscar Apfel Produced by Selig Enterprises Presented in a selected list of cities By the American Committee for ARMENIAN AND SYRIAN RELIEF J. C. & A. L. Fawcett, Inc. Publishers 38-01 23rd AVENUE ASTORIA, N. Y. 11105 © 1990, MICHAEL KEHYAIAN PRINTING; COLOR LITHO, Made in U.S.A, ISBN 0-914567-11-7 MY DEDICATION each mother and father, in this beautiful land ^ of the United States, who has taught a daughter to believe in God, I dedicate my book. I saw my own mother's body, its life ebbed out, flung onto the desert because she had taught me that Jesus Christ was my Saviour. I saw my father die in pain because he said to me, his little girl, “Trust in the Lord; His will be done." I saw thousands upon thousands of beloved daughters of gentle mothers die under the whip, or the knife, or from the torture of hunger and thirst, or carried away into slavery because they would not renounce the glorious crown of their Christianity. -

Documenting Protestant Missionary Activism During the Armenian Genocide

Philanthropy, Faith, and Influence: Documenting Protestant Missionary Activism during the Armenian Genocide Elizabeth N. Call and Matthew Baker, Columbia University Author Note: Elizabeth N. Call, Public Services Librarian, The Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary, Columbia University in the City of New York; Matthew Baker, Collection Services Librarian, The Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary, Columbia University in the City of New York. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Elizabeth Call The Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary 3041 Broadway New York, NY 10027 Contact: [email protected] Philanthropy, Faith, and Influence | The Reading Room | Volume 1, Issue 1 7 Abstract American Protestant missionaries played important political and cultural roles in the late Ottoman Empire in the period before, during, and after the Armenian genocide. They reported on events as they unfolded and were instrumental coordinating and executing relief efforts by Western governments and charities. The Burke Library’s Missionary Research Library, along with several other important collections at Columbia and other nearby research repositories, holds a uniquely rich and comprehensive body of primary and secondary source materials for understanding the genocide through the lens of the missionaries’ attempts to document and respond to the massacres. Keywords: Armenian genocide, Turkey, missionaries, Near East, WWI, Middle East Christianity Philanthropy, Faith, and Influence | The Reading Room | Volume 1, Issue 1 8 Philanthropy, Faith, and Influence: Documenting Protestant Missionary Activism during the Armenian Genocide Elizabeth N. Call and Matthew Baker, Columbia University April 2015 marks the centenary of the beginning of the Armenian genocide, in which an estimated 1 to 1.5 million members of the indigenous and ancient Christian minority in what is now eastern Turkey, along with many co-religionists from the Assyrian and Greek Orthodox communities, perished through forced deportation or execution (Kevorkian, 2011). -

By Any Other Name: How, When, and Why the US Government Has Made

By Any Other Name How, When, and Why the US Government Has Made Genocide Determinations By Todd F. Buchwald Adam Keith CONTENTS List of Acronyms ................................................................................. ix Introduction ........................................................................................... 1 Section 1 - Overview of US Practice and Process in Determining Whether Genocide Has Occurred ....................................................... 3 When Have Such Decisions Been Made? .................................. 3 The Nature of the Process ........................................................... 3 Cold War and Historical Cases .................................................... 5 Bosnia, Rwanda, and the 1990s ................................................... 7 Darfur and Thereafter .................................................................... 8 Section 2 - What Does the Word “Genocide” Actually Mean? ....... 10 Public Perceptions of the Word “Genocide” ........................... 10 A Legal Definition of the Word “Genocide” ............................. 10 Complications Presented by the Definition ...............................11 How Clear Must the Evidence Be in Order to Conclude that Genocide has Occurred? ................................................... 14 Section 3 - The Power and Importance of the Word “Genocide” .. 15 Genocide’s Unique Status .......................................................... 15 A Different Perspective .............................................................. -

The Anne Frank of the Armenian Genocide

Keghart The Anne Frank of the Armenian Genocide Non-partisan Website Devoted to Armenian Affairs, Human Rights https://keghart.org/the-anne-frank-of-the-armenian-genocide/ and Democracy THE ANNE FRANK OF THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE Posted on April 29, 2014 by Keghart Category: Opinions Page: 1 Keghart The Anne Frank of the Armenian Genocide Non-partisan Website Devoted to Armenian Affairs, Human Rights https://keghart.org/the-anne-frank-of-the-armenian-genocide/ and Democracy Vartan Matiossian & Alan Whitehorn, National Post, 29 April 2014 April is Genocide Awareness Month, an opportunity for people around the world to remember the victims of such events as the Rwandan Genocide, the Holocaust and the Armenian Genocide. Vartan Matiossian & Alan Whitehorn, National Post, 29 April 2014 April is Genocide Awareness Month, an opportunity for people around the world to remember the victims of such events as the Rwandan Genocide, the Holocaust and the Armenian Genocide. Amidst the mass deportations and killings of Armenians that began in April, 1915, some of the targeted civilian victims survived. One was a young orphan girl, Arshaluys Mardigian (1901-1994), who lived just north of the city of Harpout in the Ottoman Empire. While most of her family was killed, she managed to flee the massacres and eventually immigrated as a teenager to the United States, where she lived initially under the auspices of an official of the American Committee of Armenian and Syrian Relief (later to become the highly influential international aid organization Near East Relief). Upon her arrival, the young orphan was interviewed by American reporters about her horrific experiences. -

Preliminary Program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28Th 2020

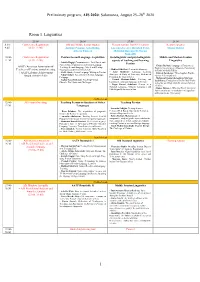

Preliminary program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28th 2020 Room 1. Linguistics 25.08 26.08 27.08 28.08 8:30- Conference Registration Old and Middle Iranian studies Plenary session: Iran-EU relations Keynote speaker 9:45 (8:30–12:00) Antonio Panaino, Götz König, Luciano Zaccara, Rouzbeh Parsi, Maziar Bahari Alberto Cantera Mehrdad Boroujerdi, Narges Bajaoghli 10:00- Conference Registration Persian Second Language Acquisition Sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic Middle and Modern Iranian 11:30 (8:30–12:00) aspects of teaching and learning Linguistics - Latifeh Hagigi: Communicative, Task-Based, and Persian Content-Based Approaches to Persian Language - Chiara Barbati: Language of Paratexts as AATP (American Association of Teaching: Second Language, Mixed and Heritage Tool for Investigating a Monastic Community - Mahbod Ghaffari: Persian Interlanguage Teachers of Persian) annual meeting Classrooms at the University Level in Early Medieval Turfan - Azita Mokhtari: Language Learning + AATP Lifetime Achievement - Ali R. Abasi: Second Language Writing in Persian - Zohreh Zarshenas: Three Sogdian Words ( Strategies: A Study of University Students of (m and ryżי k .kי rγsי β יי Nahal Akbari: Assessment in Persian Language - Award (10:00–13:00) Persian in the United States Pedagogy - Mahmoud Jaafari-Dehaghi & Maryam - Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi: Teaching and - Asghar Seyed-Ghorab: Teaching Persian Izadi Parsa: Evaluation of the Prefixed Verbs learning the formulaic language in Persian Ghazals: The Merits and Challenges in the Ma’ani Kitab Allah Ta’ala -

Affirming Genocide Knowledge Through Rituals

6 Affirming Genocide Knowledge through Rituals Parts I and II of this book examined the emergence of repertoires of knowledge regarding the Armenian genocide through social interaction, objectified thought processes, bearing witness, and the involvement of knowledge entrepreneurs. We saw how knowledge generated through these processes took radically different shapes as it became sedimented within each of two distinct carrier groups, Arme- nians and Turks. Oppositional worldviews and associated knowledge reper toires are not unique to this case, of course. We find them, for example, when those who recognize the role of human action in global warming encounter others who see a Chinese conspiracy at work, aimed at harming the U.S. economy. Or again, when those who know that liberal or social democracy will secure a prosperous and secure future disagree with followers of populist authoritarian leaders and parties. The question arises of how each collectivity deals with the challenges posed by the other side. Now, in part III, we encounter two strategies commonly deployed in struggles over knowledge. While chapters 7 and 8 address conflictual engagement with the opposing side in the realms of politics and law, and chapter 9 explores counterpro- ductive effects of denial in an age of human rights hegemony, the present chapter examines the use of elaborate public rituals toward the reaffirmation of genocide knowledge within each of the contending collectivities. We owe early social-scientific insights into the role of rituals in social life to Émile Durkheim. In his book The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, Durkheim ([1912] 2001) tells us about the ability of rituals to sanctify objects and charge sym- bols that represent them with a special energy.