Supervisor, Facilitator and Arbitrator: UNIVERSITY of OSLO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United Nations As a Permanent World Organization

THE UNITED NATIONS AS A PERMANENT WORLD ORGANIZATION By ERIK COLBAN Former Norvegian Ambassador to the United Kingdom. Even those of us, who stille are young, have lived in the time of the Yeague of Nations. We know that that attempt to create a lasting world organization for peace and friendly collaboration be- tween the peoples did not succeed. We now have the United Nations. Is there a prospect that this new attempt, with the same purpose, will prove more capable of surviving? To clear our minds on this question we should begin by con- sidering on general lines the tasks of the organization. We shall then be in a better position to see, how it must be constructed so as to be able. to perform these tasks and survive. The tasks are two-fold: political and non-political. Two world - wars made it natural to place the political task - to secure peace in the foreground both in the Covenant of the League of Nations and in the Charter of the United Nations. But both documents gave also the organization the task to solve economic, social, cultural and humanitarian problems. Let us first examine the political task: consideration and settle- ment of international disputes. On this subject the system embodied in the Charter of the United Nations is in general the same as that of the Covenant of the League of Nations: the Member States undertake to stand one for all and all for one against the State which violates the peace. The system failed in the days of the League, because the States which violated the peace were Great Powers and because the United States of America remained outside the orga- nization. -

1 Introduction

Notes 1 Introduction 1. Donald Macintyre, Narvik (London: Evans, 1959), p. 15. 2. See Olav Riste, The Neutral Ally: Norway’s Relations with Belligerent Powers in the First World War (London: Allen and Unwin, 1965). 3. Reflections of the C-in-C Navy on the Outbreak of War, 3 September 1939, The Fuehrer Conferences on Naval Affairs, 1939–45 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1990), pp. 37–38. 4. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 10 October 1939, in ibid. p. 47. 5. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 8 December 1939, Minutes of a Conference with Herr Hauglin and Herr Quisling on 11 December 1939 and Report of the C-in-C Navy, 12 December 1939 in ibid. pp. 63–67. 6. MGFA, Nichols Bohemia, n 172/14, H. W. Schmidt to Admiral Bohemia, 31 January 1955 cited by Francois Kersaudy, Norway, 1940 (London: Arrow, 1990), p. 42. 7. See Andrew Lambert, ‘Seapower 1939–40: Churchill and the Strategic Origins of the Battle of the Atlantic, Journal of Strategic Studies, vol. 17, no. 1 (1994), pp. 86–108. 8. For the importance of Swedish iron ore see Thomas Munch-Petersen, The Strategy of Phoney War (Stockholm: Militärhistoriska Förlaget, 1981). 9. Churchill, The Second World War, I, p. 463. 10. See Richard Wiggan, Hunt the Altmark (London: Hale, 1982). 11. TMI, Tome XV, Déposition de l’amiral Raeder, 17 May 1946 cited by Kersaudy, p. 44. 12. Kersaudy, p. 81. 13. Johannes Andenæs, Olav Riste and Magne Skodvin, Norway and the Second World War (Oslo: Aschehoug, 1966), p. -

Scandinavian Journal of History, 44(4), 454-483

Coversheet This is the accepted manuscript (post-print version) of the article. Contentwise, the accepted manuscript version is identical to the final published version, but there may be differences in typography and layout. How to cite this publication Please cite the final published version: Gram-Skjoldager, K., Ikonomou, H., & Kahlert, T. (2019). Scandinavians and the League of Nations Secretariat, 1919-1946. Scandinavian Journal of History, 44(4), 454-483. https://doi.org/10.1080/03468755.2019.1566170 Publication metadata Title: Scandinavians and the League of Nations Secretariat, 1919-1946 Author(s): Karen Gram-Skjoldager, Haakon A. Ikonomou & Torsten Kahlert Journal: Scandinavian Journal of History DOI/Link: 10.1080/03468755.2019.1566170 Document version: Accepted manuscript (post-print) General Rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. If the document is published under a Creative Commons license, this applies instead of the general rights. This coversheet template is made available by AU Library Version 2.0, December 2017 Scandinavians and the League of Nations Secretariat, 1919-1946 Karen Gram-Skjoldager, Haakon A. -

Documenting Protestant Missionary Activism During the Armenian Genocide

Philanthropy, Faith, and Influence: Documenting Protestant Missionary Activism during the Armenian Genocide Elizabeth N. Call and Matthew Baker, Columbia University Author Note: Elizabeth N. Call, Public Services Librarian, The Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary, Columbia University in the City of New York; Matthew Baker, Collection Services Librarian, The Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary, Columbia University in the City of New York. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Elizabeth Call The Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary 3041 Broadway New York, NY 10027 Contact: [email protected] Philanthropy, Faith, and Influence | The Reading Room | Volume 1, Issue 1 7 Abstract American Protestant missionaries played important political and cultural roles in the late Ottoman Empire in the period before, during, and after the Armenian genocide. They reported on events as they unfolded and were instrumental coordinating and executing relief efforts by Western governments and charities. The Burke Library’s Missionary Research Library, along with several other important collections at Columbia and other nearby research repositories, holds a uniquely rich and comprehensive body of primary and secondary source materials for understanding the genocide through the lens of the missionaries’ attempts to document and respond to the massacres. Keywords: Armenian genocide, Turkey, missionaries, Near East, WWI, Middle East Christianity Philanthropy, Faith, and Influence | The Reading Room | Volume 1, Issue 1 8 Philanthropy, Faith, and Influence: Documenting Protestant Missionary Activism during the Armenian Genocide Elizabeth N. Call and Matthew Baker, Columbia University April 2015 marks the centenary of the beginning of the Armenian genocide, in which an estimated 1 to 1.5 million members of the indigenous and ancient Christian minority in what is now eastern Turkey, along with many co-religionists from the Assyrian and Greek Orthodox communities, perished through forced deportation or execution (Kevorkian, 2011). -

FABRICATING FIDELITY: NATION-BUILDING, INTERNATIONAL LAW, and the GREEK-TURKISH POPULATION EXCHANGE by Umut Özsu a Thesis

FABRICATING FIDELITY: NATION-BUILDING, INTERNATIONAL LAW, AND THE GREEK-TURKISH POPULATION EXCHANGE by Umut Özsu A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Juridical Sciences Faculty of Law University of Toronto © Copyright by Umut Özsu (2011) Abstract FABRICATING FIDELITY: NATION-BUILDING, INTERNATIONAL LAW, AND THE GREEK-TURKISH POPULATION EXCHANGE Umut Özsu Doctor of Juridical Sciences (S.J.D.) Faculty of Law University of Toronto 2011 This dissertation concerns a crucial episode in the international legal history of nation-building: the Greek-Turkish population exchange. Supported by Athens and Ankara, and implemented largely by the League of Nations, the population exchange showcased the new pragmatism of the post-1919 order, an increased willingness to adapt legal doctrine to local conditions. It also exemplified a new mode of non-military nation-building, one initially designed for sovereign but politico-economically weak states on the semi-periphery of the international legal order. The chief aim here, I argue, was not to organize plebiscites, channel self-determination claims, or install protective mechanisms for vulnerable minorities Ŕ all familiar features of the Allied Powers‟ management of imperial disintegration in central and eastern Europe after the First World War. Nor was the objective to restructure a given economy and society from top to bottom, generating an entirely new legal order in the process; this had often been the case with colonialism in Asia and Africa, and would characterize much of the mandates system ii throughout the interwar years. Instead, the goal was to deploy a unique mechanism Ŕ not entirely in conformity with European practice, but also distinct from non-European governance regimes Ŕ to reshape the demographic composition of Greece and Turkey. -

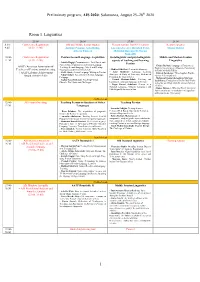

Preliminary Program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28Th 2020

Preliminary program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28th 2020 Room 1. Linguistics 25.08 26.08 27.08 28.08 8:30- Conference Registration Old and Middle Iranian studies Plenary session: Iran-EU relations Keynote speaker 9:45 (8:30–12:00) Antonio Panaino, Götz König, Luciano Zaccara, Rouzbeh Parsi, Maziar Bahari Alberto Cantera Mehrdad Boroujerdi, Narges Bajaoghli 10:00- Conference Registration Persian Second Language Acquisition Sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic Middle and Modern Iranian 11:30 (8:30–12:00) aspects of teaching and learning Linguistics - Latifeh Hagigi: Communicative, Task-Based, and Persian Content-Based Approaches to Persian Language - Chiara Barbati: Language of Paratexts as AATP (American Association of Teaching: Second Language, Mixed and Heritage Tool for Investigating a Monastic Community - Mahbod Ghaffari: Persian Interlanguage Teachers of Persian) annual meeting Classrooms at the University Level in Early Medieval Turfan - Azita Mokhtari: Language Learning + AATP Lifetime Achievement - Ali R. Abasi: Second Language Writing in Persian - Zohreh Zarshenas: Three Sogdian Words ( Strategies: A Study of University Students of (m and ryżי k .kי rγsי β יי Nahal Akbari: Assessment in Persian Language - Award (10:00–13:00) Persian in the United States Pedagogy - Mahmoud Jaafari-Dehaghi & Maryam - Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi: Teaching and - Asghar Seyed-Ghorab: Teaching Persian Izadi Parsa: Evaluation of the Prefixed Verbs learning the formulaic language in Persian Ghazals: The Merits and Challenges in the Ma’ani Kitab Allah Ta’ala -

Book Chapter

Book Chapter Ravished Armenia (1919): Bearing witness in the age of mechanical reproduction. Some thoughts on a film-ordeal GARIBIAN, Sévane Abstract "Ravished Armenia, also entitled Auction of Souls, is the only film of its kind, being based on the testimony of the young Aurora Mardiganian (real name Archaluys Mardigian), who survived the Armenian genocide and exiled in the United States on 1917, aged sixteen. This 1919 silent film is based on a script written by the editors of Aurora’s memoirs. Produced by a pioneer of American cinema, on behalf of the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, it was shot in record time and featured a star cast, Hollywood sets and hundreds of extras. At the top of the bill was Aurora herself. Initially presented as a cinematografic work with a charitable objective, Ravished Armenia was above all a blockbuster, designed to create a commercial sensation amidst which the original witness, dispossessed of her own story, would be lost. The few remaining images/traces (only one reel, as the others had misteriously disappeared) of what was the first cinematografic reconstitution of a genocide narrated by a female survivor testify in themselves to two things: both to the Catastrophe, through the screening of the body-as-witness in [...] Reference GARIBIAN, Sévane. Ravished Armenia (1919): Bearing witness in the age of mechanical reproduction. Some thoughts on a film-ordeal. In: Chabot, Joceline ; Godin, Richard ; Kappler, Stefanie ; Kasparian, Sylvia. Mass Media and the Genocide of the Armenians : One Hundred Years of Uncertain Representation. Basingstoke : Palgrave Mcmillan, 2015. p. 36-50 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:77313 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. -

Havana Charter for an International Trade Organization, Including Annexes 9

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND EMPLOYMENT HELD AT HAVANA, CUBA FROM NOVEMBER 21, 1947, TO MARCH 24, 1948 _______________ FINAL ACT AND RELATED DOCUMENTS INTERIM COMMISSION FOR THE INTERNATIONAL TRADE ORGANIZATION LAKE SUCCESS, NEW YORK APRIL, 1948 - 2 - The present edition of the Final Act and Related Documents has been reproduced from the text of the signature copy and is identical with that contained in United Nations document E/Conf. 2/78. This edition has been issued in larger format in order to facilitate its use by members of the Interim Commission. - 3 - FINAL ACT OF THE UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND EMPLOYMENT - 4 - TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. Final Act of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Employment VII II. Havana Charter for an International Trade Organization, including Annexes 9 III. Resolutions adopted by the Conference 117 - 5 - FINAL ACT OF THE UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND EMPLOYMENT The Economic and Social Council of the United Nations, by a resolution dated February 18, 1946, resolved to call an International Conference on Trade and Employment for the purpose of promoting the expansion of the production, exchange and consumption of goods. The Conference, which met at Havana on November 21, 1947, and ended on March 24, 1948, drew up the Havana Charter for an International Trade Organization to be submitted to the Governments represented. The text of the Charter in the English and French languages is annexed hereto and is hereby authenticated. The authentic text of the Charter in the Chinese, Russian and Spanish languages will be established by the Interim Commission of the International Trade Organization, in accordance with the procedure approved by the Conference. -

Who's Afraid of Violent Language?

01 ANT 3-3 Cowan (JB/D) 7/8/03 1:03 pm Page 271 Anthropological Theory Copyright © 2003 SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi) Vol 3(3): 271–291 [1463-4996(200309)3:3;271–291;035238] Who’s afraid of violent language? Honour, sovereignty and claims-making in the League of Nations Jane K. Cowan University of Sussex, UK Abstract The peace treaties following the Great War dictated that certain nation-states accept, as the price of international recognition, agreements to protect the rights of their minority populations. Responsibility to ‘guarantee’ and ‘supervise’ the minority treaties fell to a novel and untried international institution, the League of Nations. It established the ‘minority petition procedure’, an unprecedented innovation within international relations that initiated transnational claims-making. Focusing on the supervision of agreements pertaining to the Macedonian region, I examine how the Minorities Section of the League of Nations Secretariat handled ‘minority petitions’ alleging state infractions of minority treaties. I consider, in particular, a preoccupation among both bureaucrats and states with ‘violent language’ in petitions. I argue that this preoccupation signalled anxieties about honour, sovereignty and legitimacy, about the ambiguous position of ‘minority states’ and about the potentially explosive effects of popular energies in the post-war international order. Key Words bureaucracy • claims-making • international institutions • League of Nations • minorities • minority treaties • petitions • rights • sovereignty • violent language The redrawing of European state boundaries at the Versailles Peace Conference in 1918–1919 had dramatic consequences for the inhabitants of the now disintegrated Ottoman, Hapsburg and Romanov empires. If the peace settlement gave 60 million ‘their own’ national state, more than half that number, who saw themselves, or were seen by others, as distinct from the majority population, confronted a different fate. -

Missions, Charity, and Humanitarian Action in the Levant (19Th–20Th Century) 21 Chantal Verdeil

Christian Missions and Humanitarianism in the Middle East, 1850–1950 Leiden Studies in Islam and Society Editors Léon Buskens (Leiden University) Nathal M. Dessing (Leiden University) Petra M. Sijpesteijn (Leiden University) Editorial Board Maurits Berger (Leiden University) – R. Michael Feener (Oxford University) – Nico Kaptein (Leiden University) Jan Michiel Otto (Leiden University) – David S. Powers (Cornell University) volume 11 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/lsis Christian Missions and Humanitarianism in the Middle East, 1850–1950 Ideologies, Rhetoric, and Practices Edited by Inger Marie Okkenhaug Karène Sanchez Summerer LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: “Les Capucins français en Syrie. Secours aux indigents”. Postcard, Collection Gélébart (private collection), interwar period. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Okkenhaug, Inger Marie, editor. | Sanchez Summerer, Karène, editor. Title: Christian missions and humanitarianism in the Middle East, 1850-1950 : ideologies, rhetoric, and practices / edited by Inger Marie Okkenhaug, Karène Sanchez Summerer. Other titles: Leiden studies in Islam and society ; v. 11. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. -

NEAR EAST FOUNDATION Annual Report 2014

NEAR EAST FOUNDATION Annual Report 2014 BOARD OF DIRECTORS HONORARY BOARD Shant Mardirossian, Chair Shahnaz Batmanghelid Johnson Garrett, Vice Chair Amir Ali Farman-Farma, Ph.D. Haig Mardikian, Secretary John Goelet Charles Benjamin, Ph.D., President John Grammer Mehrzad Boroujerdi, Ph.D. Ronald Miller Mona Eraiba David Mize Alexander Ghiso Abe Moses Jeff Habib Richard Robarts Linda K. Jacobs, Ph.D. Anthony Williams Amr Nosseir Tarek Younes Matthew Quigley Soroush Shehabi PRESIDENT’S COUNCIL Robert Solomon William Sullivan H.E. Andre Azoulay Harris Williams Ian Bremmer Ambassador Edward P. Djerejian Vartan Gregorian, Ph.D. ACADEMIC COUNCIL Ambassador Richard W. Murphy John Kerr, Ph.D. Her Majesty Queen Noor of Jordan John McPeak, Ph.D. James Steinberg Thomas Mullins Ambassador Frank G. Wisner Juliet Sorensen, J.D. Michaela Walsh On the Cover: Schoolgirls in Morocco’s High Atlas Mountains. NEAR EAST FOUNDATION Annual Report 2014 Near East Foundation at 100: Celebrating the Past, Shaping the Future Near East Relief orphans at Antylas - lesson on the beach, c. 1920s. This year marks the 100th anniversary volunteered to go to the region to offer of the founding of Near East Relief, as food, medical care, and educational and Near East Relief Historical the Near East Foundation was known vocational training for adults and children. Society originally, which was created in 1915 This heroic effort marked the first great In 2014, NEF created the Near East to help rescue an estimated 1.5 million outpouring of American humanitarian Relief Historical Society to raise Armenian refugees and orphans after the assistance—giving birth to citizen awareness about this important collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the philanthropy, a movement that embodies chapter in American history. -

History Stands to Repeat Itself As Armenia Renews Ties to Asia

THE ARMENIAN GENEALOGY MOVEMENT P.38 ARMENIAN GENERAL BENEVOLENT UNION AUG. 2019 History stands to repeat itself as Armenia renews ties to Asia Armenian General Benevolent Union ESTABLISHED IN 1906 Հայկական Բարեգործական Ընդհանուր Միութիւն Central Board of Directors President Mission Berge Setrakian To promote the prosperity and well-being of all Armenians through educational, Honorary Member cultural, humanitarian, and social and economic development programs, projects His Holiness Karekin II, and initiatives. Catholicos of All Armenians Annual International Budget Members USD UNITED STATES Forty-six million dollars ( ) Haig Ariyan Education Yervant Demirjian 24 primary, secondary, preparatory and Saturday schools; scholarships; alternative Eric Esrailian educational resources (apps, e-books, AGBU WebTalks and more); American Nazareth A. Festekjian University of Armenia (AUA); AUA Extension-AGBU Artsakh Program; Armenian Arda Haratunian Virtual College (AVC); TUMO x AGBU Sarkis Jebejian Ari Libarikian Cultural, Humanitarian and Religious Ani Manoukian AGBU News Magazine; the AGBU Humanitarian Emergency Relief Fund for Syrian Lori Muncherian Armenians; athletics; camps; choral groups; concerts; dance; films; lectures; library research Levon Nazarian centers; medical centers; mentorships; music competitions; publications; radio; scouts; Yervant Zorian summer internships; theater; youth trips to Armenia. Armenia: Holy Etchmiadzin; AGBU ARMENIA Children’s Centers (Arapkir, Malatya, Nork), and Senior Dining Centers; Hye Geen Vasken Yacoubian