Appendix 2 Dissertation Steven De Waal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Van Het 13De Congres Van De Socialistische Partij V E R S L

VERSLAG van het 13de congres van de Socialistische Partij 2 8 m e i 2 0 0 5 D e V e r e e n i g i n g N i j m e g e n 3 Verslag van het 13de congres van de Socialistische Partij op 28 mei 2005 Voorzitters Riet de Wit / Bob Ruers Secretaris Paulus Jansen Congrescommissie Harry van Bommel, Hans van Heijningen en Paulus Jansen Stembureau Jean-Louis van Os en Remine Alberts 4 Opening door Hans van Hooft namens het college van burgemeester en wethouders van Nijmegen Hans van Hooft: dames en heren, vrienden, vriendinnen en kameraden, ik ben Hans van Hooft, lid van het stropdasloze college in Nijmegen, maar heb wel een stropdas om bij belangrijke gebeurtenissen zo- als nu. Ik heet het congres namens het gemeentebestuur van Nijmegen hartelijk welkom in deze mooie stad, waar dit jaar het 2000 jarig bestaan wordt gevierd. Ik complimenteer het partijbestuur met hun keuze dit monumentale gebouw voor het SP congres te huren en hoop dat de discussie vandaag over ‘heel de wereld’ met veel passie zal worden gevoerd. Ik wens, mede namens het gemeentebestuur, alle aanwezigen een goed congres! Riet de Wit (voorzitter) dankt Hans van Hooft voor zijn vriendelijke woorden en geeft aan graag in Nijmegen te gast te zijn waar ook Peter Lucassen namens de SP-fractie zitting heeft in het (nog) enige linkse college in Nederland. Zij merkt op dat Nijmegen meer dan een rood college en 2000 jaar ge- schiedenis heeft en doelt met name op de toekomst in de vorm van aanstormend talent, nog heel jong, maar al geprezen en bekroond en stelt Pieter Derks voor. -

"Overweldigend Nee Tegen Europese Grondwet" in <I>De Volkskrant</I

"Overweldigend nee tegen Europese Grondwet" in De Volkskrant (2 juni 2005) Source: De Volkskrant. 02.06.2005. Amsterdam. Copyright: (c) de Volkskrant bv URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/"overweldigend_nee_tegen_europese_grondwet"_in_de_volkskrant_2_juni_2005-nl- b40c7b58-b110-4b79-b92a-faf4da2bc4e0.html Publication date: 19/09/2012 1 / 3 19/09/2012 Overweldigend nee tegen Europese Grondwet Van onze verslaggevers DEN HAAG/ BRUSSEL - Een overgrote meerderheid (bijna 62 procent) van de Nederlandse kiezers heeft de Europese Grondwet afgewezen. Premier Balkenende zei woensdagavond dat hij ‘zeer teleurgesteld’ is. Maar het kabinet ‘zal de uitslag respecteren en rechtdoen’. Balkenende: ‘Nee is nee. Wij begrijpen de zorgen. Over het verlies aan soevereiniteit, over het tempo van de veranderingen in Europa zonder dat de burgers zich daarbij betrokken voelen, over onze financiële bijdrage aan Brussel. En daar moet in Europa rekening mee worden gehouden’. De premier beloofde deze punten aan te snijden tijdens de Europese topconferentie later deze maand in Brussel. De Tweede Kamer zal vandaag het kabinet vragen om het voorstel tot goedkeuring van de Grondwet in te trekken. Balkenende en vice-premier Gerrit Zalm (VVD) gaven aan dat ze dat zullen doen. Nederland is na Frankrijk het tweede land dat de Grondwet afwijst. In Frankrijk stemde 55 procent van de bevolking tegen de Grondwet. In Nederland blijkt zelfs 61,6 procent van de kiezers tegen; 38,4 procent stemde voor. De opkomst was met 62,8 procent onverwacht hoog. Bij de laatste Europese verkiezingen in Nederland kwam slechts 39,1 procent van de stemgerechtigden op. In Brussel werd woensdag met teleurstelling gereageerd. De Luxemburgse premier Jean-Claude Juncker, dienstdoend voorzitter van de EU, verwacht niettemin dat de Europese leiders deze maand zullen besluiten om het proces van ratificatie (goedkeuring) van de Grondwet in alle 25 lidstaten voort te zetten. -

How Populist Are the People? Measuring Populist Attitudes in Voters Agnes Akkerman Cas Mudde, University of Georgia Andrej Zaslove, Radboud University Nijmegen

University of Georgia From the SelectedWorks of Cas Mudde 2014 How Populist are the People? Measuring Populist Attitudes in Voters Agnes Akkerman Cas Mudde, University of Georgia Andrej Zaslove, Radboud University Nijmegen Available at: https://works.bepress.com/cas_mudde/95/ CPSXXX10.1177/0010414013512600Comparative Political StudiesAkkerman et al. 512600research-article2013 Article Comparative Political Studies 2014, Vol. 47(9) 1324 –1353 How Populist Are the © The Author(s) 2013 Reprints and permissions: People? Measuring sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0010414013512600 Populist Attitudes in cps.sagepub.com Voters Agnes Akkerman1, Cas Mudde2, and Andrej Zaslove3 Abstract The sudden and perhaps unexpected appearance of populist parties in the 1990s shows no sign of immediately vanishing. The lion’s share of the research on populism has focused on defining populism, on the causes for its rise and continued success, and more recently on its influence on government and on public policy. Less research has, however, been conducted on measuring populist attitudes among voters. In this article, we seek to fill this gap by measuring populist attitudes and to investigate whether these attitudes can be linked with party preferences. We distinguish three political attitudes: (1) populist attitudes, (2) pluralist attitudes, and (3) elitist attitudes. We devise a measurement of these attitudes and explore their validity by way of using a principal component analysis on a representative Dutch data set (N = 600). We indeed find three statistically separate scales of political attitudes. We further validated the scales by testing whether they are linked to party preferences and find that voters who score high on the populist scale have a significantly higher preference for the Dutch populist parties, the Party for Freedom, and the Socialist Party. -

Download ZO-Krant Derde Editie • Najaar 2008 (PDF)

DERDE EDITIE NAJAAR 2008 EEN BETER NEDERLAND AGNES KANT: "IK BEN GEEN SCHOOTHOND" ZO MAAK JE JE BUURT BETER JAN MARIJNISSEN HEEFT ALLE VERTROUWEN IN AGNES KANT 2 ZO VOOR EEN BETER NEDERLAND Je bent eigenlijk meester JAN in de rechten? “Ja, ik heb fiscaal recht gestudeerd MARIJNISSEN maar dat is te saai voor woorden. Ik heb zelfs nog een jaar als fiscalist COVER gewerkt, maar daar was ik alleen maar bezig te bedenken hoe grote bedrijven zo veel mogelijk voordeel van onze fiscale wetgeving konden krijgen. Toen ben ik gaan nadenken MODEL wat echt leuk en zinnig was om te doen en ben ik bij de FNV gaan werken.” FOTOGRAFIE AUKE VLEER Nog tijd voor leuke dingen? “Nou, wat dacht je van onze zoon Covermodel Ron Waarom de SP? Kyan die nu anderhalf is. Met hem Meyer (26) werkt als “Omdat de SP de enige partij is is het altijd leuk. En daarnaast ben die linkse idealen combineert met ik nog aanvoerder van een vrien- bestuurder bij FNV linkse daden.Ik ben sinds mijn denteam, waarbij ik links op het Bondgenoten en is twintigste al actief bij de SP in middenveld voetbal.” fractieleider van Heerlen, vooral bij het spreekuur de tien raadsleden van de sociale hulpdienst. En nadat FOTOGRAFIE: ARI VERSLUIS & we drie wethouders aan het College ELLIE UYttenbroek tellende SP-fractie AAN DE van B & W hadden geleverd, in Heerlen. koos de fractie me twee jaar ZIJ-KANT geleden als fractie leider.” Meer dan tien keer heb ik de troonrede in de Ridderzaal bijgewoond. Dit jaar voor het eerst niet als fractievoorzitter. -

The Netherlands from National Identity to Plural Identifications

The NeTherlaNds From NaTioNal ideNTiTy To Plural ideNTiFicaTioNs By Monique Kremer TRANSATLANTIC COUNCIL ON MIGRATION THE NETHERLANDS From National Identity to Plural Identifications Monique Kremer March 2013 Acknowledgments This research was commissioned by the Transatlantic Council on Migration, an initiative of the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), for its seventh plenary meeting, held November 2011 in Berlin. The meeting’s theme was “National Identity, Immigration, and Social Cohesion: (Re)building Community in an Ever-Globalizing World” and this paper was one of the reports that informed the Council’s discussions. The Council, an MPI initiative undertaken in cooperation with its policy partner the Bertelsmann Stiftung, is a unique deliberative body that examines vital policy issues and informs migration policymaking processes in North America and Europe. The Council’s work is generously supported by the following foundations and governments: Carnegie Corporation of New York, Open Society Foundations, Bertelsmann Stiftung, the Barrow Cadbury Trust (UK Policy Partner), the Luso-American Development Foundation, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and the governments of Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. For more on the Transatlantic Council on Migration, please visit: www.migrationpolicy.org/transatlantic. © 2013 Migration Policy Institute. All Rights Reserved. Cover Design: Danielle Tinker, MPI Typesetting: April Siruno and Rebecca Kilberg, MPI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmit- ted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and re- trieval system, without permission from the Migration Policy Institute. A full-text PDF of this document is available for free download from: www.migrationpolicy.org. Information for reproducing excerpts from this report can be found at www.migrationpolicy.org/about/copy.php. -

Evaluating Attacks on the Credibility of Politicians in Political Debates

ISSA Proceedings 2006 – Evaluating Attacks On The Credibility Of Politicians In Political Debates 1. Introduction When analysing political argumentative discourse, we regularly come across attacks on the credibility of the participants in the discourse. By discrediting tactics, politicians intend to discourage their colleague politicians and the general public from supporting the standpoint of their opponent. In Dutch media it is suggested that the use of personal attacks in Dutch political debates has increased under the influence of international politics.[i] Although there is no empirical evidence for this claim, very recently there have been several examples in Dutch politics in which the credibility of politicians has been subject of debate. On June 24 2006 for instance, the Dutch progressive liberal party, Democrats 66 (D’66), organised elections in order to find a new party leader. The two most prominent candidates were the current Minister for Government Reform and Kingdom Relations, Alexander Pechtold, and chair of the parliamentary party, Lousewies van der Laan. In one of the debates in the build-up to the elections, van der Laan stated that her opponent Pechtold, had completely lost his credibility. First of all because Pechtold, when he was a minister, had agreed on the Uruzgan mission whereas, on an earlier occasion, he had said that under no circumstances he would agree on that mission. Secondly, because he characterised himself as an analytical person, whereas, according to van der Laan, this is not in keeping with the way in which he had profiled himself in an interview, claiming to be ‘a man who often shoots and some shots are successful’. -

Onrecht Kent Geen Grenzen

ONRECHT KENT GEEN GRENZEN UITGAVE VAN HET WETENSCHAPPELIJK BUREAU VAN DE SP Verschijnt 11 keer per jaar, jaargang 15, nummer 6, juni 2013 ONRECHT KENT INHOUD 3 GEEN GRENZEN OORLOG EN VREDE IN HET MIDDEN-OOSTEN 6 RAMPEN IN DE TEXTIELFABRIEKEN In dit laatste nummer van Spanning de crisis in het kader van de studieda- VAN BANGLADESH voor de zomer vertelt SP-senator Tiny gen van de Europees Verenigd Links/ 8 Kox over zijn reis door het Midden- Noords Groen Linkse Eurofractie, ‘MADE IN TuRKEY’ IS GEEN GARANTIE Oosten, die hij onlangs voor de Raad waar hij namens de SP aan deelnam. VOOR EEN EERLIJK PRODUCT van Europa ondernam. Wat hij 9 constateert, is dat de situatie in Syrië Daarnaast interviewt Jan Marijnissen OBAMA BLIJFT ooRLOGSPRESIDENT ronduit schrijnend is en dat een zijn collega Jan de Wit over het mede 10 levensvatbare, onafhankelijke door hem ingediende wetsvoorstel, LINKS EuROPA LEERT VAN ELKAAR Palestijnse staat nog ver weg is. dat onlangs door een Kamermeerder- 12 heid werd aangenomen, om de JAN DE WIT OVER BELEDIGING, Fractiemedewerker Economische bepalingen rond Godslastering uit het GODSLASTERING EN DE VRIJHEID Zaken Sjoerd van Dijk betoogt in zijn Wetboek van Strafrecht te schrappen. VAN MENINGSUITING bijdrage dat de ramp die zich onlangs 14 voordeed in een textielfabriek in SP-Tweede Kamerlid en woordvoerder VERHuuRDERHEFFING NEE! Bangladesh slechts een druppel op de Wonen Paulus Jansen presenteert in MAAR WAT DAN WEL? gloeiende plaat is. Ook in andere zijn artikel twee alternatieven voor het 16 sectoren laten de arbeidsomstandig- desastreuze woonbeleid van Rutte II. OP WEG NAAR DE WECONomY heden ernstig te wensen over en wordt Enerzijds pleit hij voor een gelijke 18 weinig werk gemaakt van maatschap- behandeling van huurders en kopers PARELS UIT DE PARLEMENTAIRE pelijk verantwoord ondernemen. -

De Risico-Regelreflex Vanuit Politiek Perspectief

De risico-regelreflex vanuit politiek perspectief Verkennend onderzoek naar de mening van Kamerleden over risico’s en politieke verantwoordelijkheid in opdracht van het Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties USBO Advies Departement Bestuurs- en Organisatiewetenschap Universiteit Utrecht Margo Trappenburg Marie-Jeanne Schiffelers Gerolf Pikker Lieke van de Camp Februari 2012 Inhoudsopgave 1. Inleiding 2 2. Vraagstelling 3 3. Aanpak 4 4. Resultaten interviews 5 a. Herkenning van het mechanisme 5 b. Waardering van het mechanisme 5 c. Van media naar Kamerlid 6 d. Parlementaire actie 7 e. Diepere reflectie 9 f. Andere betrokkenen 10 g. Mogelijkheden tot verbetering 12 5. Bevindingen reflectiebijeenkomst 7 nov. 2011 WRR 14 6. Conclusies 15 7. Aanbevelingen 18 Bijlagen: 1. Referenties 2. Lijst van respondenten 3. Itemlijst 4. Selectie inleiding Oogstbijeenkomst 5 dec. 2011 door dhr. Jan van Tol 1 1. Inleiding De huidige samenleving wordt vaak omschreven als ‘Risicosamenleving’ waarin de productie van goederen en diensten hand in hand gaat met de productie van wetenschappelijk en technologisch geproduceerde risico’s. De risicosamenleving wordt gekenmerkt door een veronderstelde verschuiving van de distributie van goederen naar de verdeling van de risico’s en gevaren (Beck, 1992). Giddens beschrijft het fenomeen ‘risk society’ als: "a society where we increasingly live on a high technological frontier which no one completely understands…. It is a society that is increasingly preoccupied with the future and with safety, which generates the notion of risk” (Giddens, 1999, p.3). De risicosamenleving heeft onder meer tot gevolg dat de overheid vaker aangesproken wordt op het afdekken van deze mogelijke risico’s voor zowel de burger als het bedrijfsleven (Ministerie BZK, 2011a). -

Hoe Populistisch Zijn Geert Wilders En Rita Verdonk?

437 Hoe populistisch zijn Geert Wilders en Rita Verdonk? Verschillen en overeenkomsten in optreden en discours van twee politici1 Koen Vossen "#453"$5 In the Netherlands, the rise of new parties such as the Lijst Pim Fortuyn, the Partij voor de Vrijheid, lead by Geert Wilders and the movement Trots op Nederland, lead by Rita Verdonk, have attracted much attention. In an attempt to interpret and explain the (temporary) advance of these parties, both commentators and political scientists have often used the notion of populism. In most commentaries however, it remains unclear what the term exactly means and whether it has any explanatory value. The aim of this article is to investigate whether Rita Verdonk and Geert Wilders and their movements may actually be labelled as populist. By discerning the presence of the features of an ideal-typical populism in discourse and performance of both politicians their ‘degree of populism’ is measured. The differences in degree of populism also helps to explain why Geert Wilders and his party proved (thus far) more successful and durable. KEYWORDS: populism, Netherlands, discourse, Geert Wilders, Rita Verdonk 1. Inleiding Bij het begin van het zomerreces in juli 2008 riep de Nederlandse actualiteitenru- 8&5&/4$)"11&-*+,&"35*,&-4 briek Netwerk 2008 uit tot ‘jaar van het populisme’. Als reden noemde de redactie de grote hoeveelheid publiciteit die in de voorafgaande maanden was uitgegaan naar twee als populistisch omschreven politici: Rita Verdonk en Geert Wilders (Netwerk 2-7-2008). Rita Verdonk had op 3 april 2008 haar nieuwe beweging ge- lanceerd, Trots Op Nederland (TON), waarmee ze een ‘nieuwe politiek’ beoogde te gaan voeren, waarbij de burger weer centraal zou moeten komen staan. -

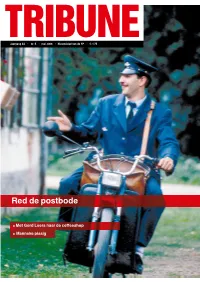

Red De Postbode

www.sp.nl Jaargang 44 • nr. 5 • mei 2008 • Nieuwsblad van de SP • € 1.75 Red de postbode “Straks alleen nog als bijbaantje” ● Met Gerd Leers naar de coffeeshop ● Manneke pissig 2 TRIBUNE JANUARI 2008 omslag0508_g.indd 2 02-05-2008 10:16:42 COLOFON UITGAVE VAN DE SOCIALISTISCHE PARTIJ (SP) verschijnt 11 maal per jaar ABONNEMENT € 5,00 per kwartaal (machtiging) of € 24,00 per jaar (acceptgiro). Losse nummers € 1,75. SP-leden ontvangen de Tribune gratis. REDACTIE Rob Janssen, Daniël de Jongh AAN DIT NUMMER WERKTEN MEE: Rick Akkerman, Patrick Arink, Maja Haanskorf, Johan van den Hout, Ronald Kennedy, Suzanne van de Kerk, Barry Smit, Bas Stoffelsen, Hans Valkhoff, Karen Veldkamp, Roel Visser VORMGEVING Robert de Klerk FIETS MEE MET DE SP Gonnie Sluijs ILLUSTRATIES van de Amstel Goldrace. Opnieuw Gideon Borman, Arend van Dam, waren leden van het SP-Wielerteam Len Munnik, Wim Stevenhagen, present om hun hobby te combineren Peter Welleman met het verwerven van aandacht voor hun partij. SP ALGEMEEN Lijkt jou dat ook wat? Stuur dan een T (010) 243 55 55 mailtje aan coördi nator René Roovers F (010) 243 55 66 ([email protected]) en je krijgt alle E [email protected] infor matie toegestuurd. Het wieler- I www.sp.nl vlnr: Peter Verschuren, Wiel Senden, team rijdt elk jaar gezamenlijk een Hans Kronenburg, Urban Spanjers, aantal tochten, waaronder in 2008 in LEDEN- EN Peter Visser, Tim Senden en René Roovers ieder geval nog de Ride for the Roses. ABONNEMENTENADMINISTRATIE En natuurlijk is de SP-fietskleding ook Vijverhofstraat 65 De tomatenoutfit schitterde op uitstekend geschikt voor trainings- 3032 SC Rotterdam 19 april weer op de Keutenberg, de ritten. -

University of Groningen Populisten in De Polder Lucardie, Anthonie

University of Groningen Populisten in de polder Lucardie, Anthonie; Voerman, Gerrit IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2012 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Lucardie, P., & Voerman, G. (2012). Populisten in de polder. Meppel: Boom. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 10-02-2018 Paul lucardie & Gerrit Voerman Omslagontwerp: Studio Jan de Boer, Amsterdam Vormgeving binnenwerk: Velotekst (B.L. van Popering), Zoetermeer Druk:Wilco,Amersfoort © 2012 de auteurs Behoudens de in of krachtens de Auteurswet van 1912 gestelde uitzonderingen mag niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch door fotokopieën, opnamen of enig andere manier, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. -

PERSPEX November

PerspexUitgave van PerspectieF, ChristenUnie-jongeren 7e jaargang | november 2006 | nr. 27 Stem Strategisch verder in dit nummer: ChristeUnie 2 goes Hyves 3 Interview nieuw kamer- stem lid joel Voordewind De formatie 5 ‘Rouvoet trapt niet in zelf- de kuil als D66 ChristenUnie 7 Wij zijn wat het CDA niet was: sociaal Bekende nederlanders 8 stemmen ChristenUnie Mensen over 9 Rogier: ‘Als je hem een keer in majo wilt zien...’ 11 Dagboek André Rouvoet PerspectieF’er krijgt extra Zakdoekjes steunt tijdens campagne Het is campagne en partijen halen jes. De hele top-tien van de kandi- alles van stal om de kiezer te verlei- datenlijst van de ChristenUnie, den. Niks is te gek. Ook voor de waaronder PerspectieF’er Ed Anker, op 22 november op de laatsge- kans. Ik heb al veel aandacht van ChristenUnie niet. Vanaf deze beschikt over een grote hoeveel- plaatsde(n)van de kandidatenlijst de media gehad. En ik merk dat de maand is het namelijk ook moge- heid zakdoekjes. De verwachting is te stemmen. mensen, zoals mijn collega’s, met lijk om je neus te snuiten met dat deze gretig aftrek zullen heb- De actie van ondersteboven.nl me meeleven.” PerspectieF-voorzitter Rogier ben. werd breed opgepakt door de Havelaar. Tv-presentator Arie Boomsma is in media. Rita kan daardoor op veel Als ze wordt gekozen heeft ze voor Niet de echte, maar met een zak- samenwerking met de media-aandacht rekenen. zichzelf een drietal speerpunten. doekje waar zijn afbeelding op ChristenUnie een campagne “Ik zou me inzetten voor meer sta- staat. Rogier beet zelf als eerste het gestart, gericht op jongeren.