Evaluating Attacks on the Credibility of Politicians in Political Debates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 2 Dissertation Steven De Waal

The Value(s) of Civil Leaders A Study into the Influence of Governance Context on Public Value Orientation Appendix 2 Portraits of Civil Leaders (13 leaders) Dissertation, University Utrecht 2014 Steven P.M. de Waal Appendix 2 Portraits of Civil Leaders (13 leaders) 1. Paul Baan 2. Hans Becker 3. Leon Bobbe 4. Piet Boekhoud (& Els Lubbers) 5. Yolanda Eijgenstein 6. Hans Nieukerke 7. Camille Oostwegel 8. Tom Rodrigues 9. Arie Schagen (& Esseline Schieven) 10. Clara and Sjaak Sies 11. Hans Visser 12. Mei Li Vos 13. Sister Giuseppa Witlox 2 Paul Baan A. Introduction Who is Paul Baan? Paul Baan was born in 1951. After finishing his bachelor of engineering, he started his career in the construction industry and later finished his master in Economics at the UniversitY of Groningen. In 1981, he joined his brother Jan at the Baan CompanY, a highlY successful software company, as president and vice-chairman. Jan and Paul Baan were successful and became verY wealthy when the company was floated. Paul Baan left the company in 1996, a Year after it went public and before it got into financial difficulties. His brother did the same sometime later. Through the Vanenburg Group, a venture capital companY investing in IT companies, also founded bY the Baan brothers, Jan and Paul Baan kept a stake in the Baan Company until the company was sold in 2000. According to Paul Baan, his passion for business and innovation stems from his time with Baan Group. In 2000, Baan started the Stichting Noaber Foundation (henceforth: Noaber Foundation). A ‘noaber’ (etYmologicallY linked to the English ‘neighbor’) is a word in an eastern Dutch dialect denoting a fellow supportive citizen. -

The Netherlands from National Identity to Plural Identifications

The NeTherlaNds From NaTioNal ideNTiTy To Plural ideNTiFicaTioNs By Monique Kremer TRANSATLANTIC COUNCIL ON MIGRATION THE NETHERLANDS From National Identity to Plural Identifications Monique Kremer March 2013 Acknowledgments This research was commissioned by the Transatlantic Council on Migration, an initiative of the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), for its seventh plenary meeting, held November 2011 in Berlin. The meeting’s theme was “National Identity, Immigration, and Social Cohesion: (Re)building Community in an Ever-Globalizing World” and this paper was one of the reports that informed the Council’s discussions. The Council, an MPI initiative undertaken in cooperation with its policy partner the Bertelsmann Stiftung, is a unique deliberative body that examines vital policy issues and informs migration policymaking processes in North America and Europe. The Council’s work is generously supported by the following foundations and governments: Carnegie Corporation of New York, Open Society Foundations, Bertelsmann Stiftung, the Barrow Cadbury Trust (UK Policy Partner), the Luso-American Development Foundation, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and the governments of Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. For more on the Transatlantic Council on Migration, please visit: www.migrationpolicy.org/transatlantic. © 2013 Migration Policy Institute. All Rights Reserved. Cover Design: Danielle Tinker, MPI Typesetting: April Siruno and Rebecca Kilberg, MPI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmit- ted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and re- trieval system, without permission from the Migration Policy Institute. A full-text PDF of this document is available for free download from: www.migrationpolicy.org. Information for reproducing excerpts from this report can be found at www.migrationpolicy.org/about/copy.php. -

University of Groningen Populisten in De Polder Lucardie, Anthonie

University of Groningen Populisten in de polder Lucardie, Anthonie; Voerman, Gerrit IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2012 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Lucardie, P., & Voerman, G. (2012). Populisten in de polder. Meppel: Boom. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 10-02-2018 Paul lucardie & Gerrit Voerman Omslagontwerp: Studio Jan de Boer, Amsterdam Vormgeving binnenwerk: Velotekst (B.L. van Popering), Zoetermeer Druk:Wilco,Amersfoort © 2012 de auteurs Behoudens de in of krachtens de Auteurswet van 1912 gestelde uitzonderingen mag niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch door fotokopieën, opnamen of enig andere manier, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. -

PERSPEX November

PerspexUitgave van PerspectieF, ChristenUnie-jongeren 7e jaargang | november 2006 | nr. 27 Stem Strategisch verder in dit nummer: ChristeUnie 2 goes Hyves 3 Interview nieuw kamer- stem lid joel Voordewind De formatie 5 ‘Rouvoet trapt niet in zelf- de kuil als D66 ChristenUnie 7 Wij zijn wat het CDA niet was: sociaal Bekende nederlanders 8 stemmen ChristenUnie Mensen over 9 Rogier: ‘Als je hem een keer in majo wilt zien...’ 11 Dagboek André Rouvoet PerspectieF’er krijgt extra Zakdoekjes steunt tijdens campagne Het is campagne en partijen halen jes. De hele top-tien van de kandi- alles van stal om de kiezer te verlei- datenlijst van de ChristenUnie, den. Niks is te gek. Ook voor de waaronder PerspectieF’er Ed Anker, op 22 november op de laatsge- kans. Ik heb al veel aandacht van ChristenUnie niet. Vanaf deze beschikt over een grote hoeveel- plaatsde(n)van de kandidatenlijst de media gehad. En ik merk dat de maand is het namelijk ook moge- heid zakdoekjes. De verwachting is te stemmen. mensen, zoals mijn collega’s, met lijk om je neus te snuiten met dat deze gretig aftrek zullen heb- De actie van ondersteboven.nl me meeleven.” PerspectieF-voorzitter Rogier ben. werd breed opgepakt door de Havelaar. Tv-presentator Arie Boomsma is in media. Rita kan daardoor op veel Als ze wordt gekozen heeft ze voor Niet de echte, maar met een zak- samenwerking met de media-aandacht rekenen. zichzelf een drietal speerpunten. doekje waar zijn afbeelding op ChristenUnie een campagne “Ik zou me inzetten voor meer sta- staat. Rogier beet zelf als eerste het gestart, gericht op jongeren. -

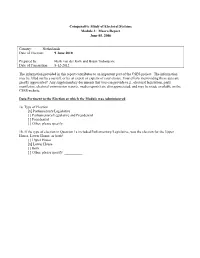

Macro Report June 05, 2006

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 3: Macro Report June 05, 2006 Country: Netherlands Date of Election: 9 June 2010 Prepared by: Henk van der Kolk and Bojan Todosijevic Date of Preparation: 8-12-2012 The information provided in this report contributes to an important part of the CSES project. The information may be filled out by yourself, or by an expert or experts of your choice. Your efforts in providing these data are greatly appreciated! Any supplementary documents that you can provide (e.g., electoral legislation, party manifestos, electoral commission reports, media reports) are also appreciated, and may be made available on the CSES website. Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1a. Type of Election [x] Parliamentary/Legislative [ ] Parliamentary/Legislative and Presidential [ ] Presidential [ ] Other; please specify: __________ 1b. If the type of election in Question 1a included Parliamentary/Legislative, was the election for the Upper House, Lower House, or both? [ ] Upper House [x] Lower House [ ] Both [ ] Other; please specify: __________ 2a. What was the party of the president prior to the most recent election? N.A. (Parliamentary system) 2b. What was the party of the Prime Minister prior to the most recent election? CDA 2c. Report the number of cabinet ministers of each party or parties in cabinet, prior to the most recent election. (If one party holds all cabinet posts, simply write "all".) Ministers are considered those members of government who are members of the Cabinet and who have Cabinet voting rights. Name of Political Party Number of Cabinet Ministers CDA 8 ministers PvdA 6 ministers CU 2 ministers 2d. -

Authentieke Versie (PDF)

(Geroffel op de bankjes) 5 De voorzitter: Afscheid vertrekkende leden Amma Asante. U hield in september een ontroerende mai- denspeech. Daarin vertelde u over uzelf. Geboren in Ghana. Aan de orde is het afscheid van de vertrekkende leden. Dochter van een voormalige fabrieksarbeider en een kamermeisje. In uw bijna 200 dagen als Kamerlid was u op De voorzitter: een prettige manier aanwezig. U pakte direct uw rol en Geachte leden, lieve collega's, beste familie en vrienden organiseerde een uitgebreide hoorzitting over botsende op de publieke tribune, vandaag is het de laatste keer dat waarden op school. Ook hebt u een omvangrijk amende- wij in deze samenstelling bij elkaar komen. Morgen wordt ment over opleidingen in het buitenland door de Kamer de nieuwe Kamer geïnstalleerd. Een deel van de aanwezigen gekregen. Bij alles was uw boodschap dat we altijd moeten zal morgen opnieuw worden beëdigd, maar van 71 collega's kijken naar de mogelijkheden van mensen, te beginnen met nemen we vandaag afscheid. Een aantal van hen heeft zelf kinderen. U bent nu een ervaring rijker en ik ben ervan te kennen gegeven met het Kamerlidmaatschap te willen overtuigd dat u deze ervaring overal kunt inzetten. Heel stoppen, een aantal is door de eigen partij niet op de lijst veel succes. gezet en een aantal moet afscheid nemen als gevolg van de verkiezingsuitslag. Zo gaat dat in onze democratie: de kiezer bepaalt wie hem of haar mag vertegenwoordigen, (Geroffel op de bankjes) en de kiezer heeft op 15 maart gesproken. De voorzitter: Afscheid hoort nu eenmaal bij de politiek, maar het is niet Daniël van der Ree. -

Jaarverslag 2007 Vvd-Hoofdbestuur

JAARVERSLAG 2007 VVD-HOOFDBESTUUR 60^ VVD-jaarverslag GJ CJ G) CJ NJ CJ CJ C:i Voorwoord Een bewogen jaar. Een politieke partij is geen gewoon bedrijf. Midden in het brandpunt van de publieke opinie. Deinend op de golven van aandacht en aanhang. Continue betrokkenheid. De VVD heeft in 2007 in het oog van de orkaan gestaan. In haar zestig jaar bestaan heeft ze veel dingen meegemaakt, maar dit 'sloeg' alles. Hoewel we allemaal dachten dat we met het hectische jaar 2006 al alles gezien hadden. De gevolgen van de ongekende lijsttrekkersverkiezingen uit dat jaar en de daarop volgende slechte uitslag voor de Tweede Kamerverkiezingen hebben het hele jaar 2007 zijn weerslag op ons handelen gehad. Continu gedoe, ondanks alle goede bedoelingen en voornemens, uiteindelijk culminerend in de gebeurtenissen van de maand september. 13 September werd RIta Verdonk uit de fractie gezet. Waarna de partij twee dagen later een zeer bewogen algemene vergadering in Veldhoven beleefde. Waar eerst slechts 600 aanwezigen verwacht werden, moest met het dubbele aantal in twee dagen tijd een groot beroep gedaan worden op het organisatie- en improvisatietalent van de medewerkers van het algemeen secretariaat. Mark Rutte kreeg de steun, maar het was nog niet afgelopen. Op 15 oktober gaf Rita Verdonk haar lidmaatschap op, nadat duidelijk was geworden dat het hoofdbestuur niets anders restte dan een royementsprocedure in gang te zetten. Op 8 december kwam het uiteindelijke slot. Ruim 1500 aanwezigen die In Rotterdam gespannen de climax meemaakten. Het doet je wat om voor zo'n volle zaal je aftreden aan te kondigen. Het jaar 2007 zal in de geschiedenis van onze WD zonder meer als een bewogen jaar te boek staan. -

Rechts, Links of Rechtschapen Een Gespreksanalytische Benadering Van Neutraliteit in Politieke Tv-Interviews

Rechts, Links of Rechtschapen Een Gespreksanalytische Benadering van Neutraliteit in Politieke Tv-interviews Masterthesis Faculteit: Geesteswetenschappen Opleiding: Communicatie- en Informatiewetenschappen Specialisatie: Communicatie-design Begeleiding: Dr. E. Huls Jasper Varwijk Tilburg, Oktober 2008 Rechts, Links of Rechtschapen Voorwoord Deze thesis is het eindresultaat van mijn afstudeeronderzoek voor de Master Communicatie- en Informatiewetenschappen aan de Universiteit van Tilburg. Een project dat achteraf ambitieuzer en tijdrovender bleek dan van te voren ooit verwacht. Dat heeft soms tot enige frustraties geleid, maar de afronding geeft daarom des te meer voldoening. Ik hoop deze voldoening te kunnen de- len met de collega’s en vrienden die hebben bijgedragen aan het tot stand komen van mijn thesis. Enkele personen verdienen in het bijzonder een ver- melding. Allereerst wil ik mijn begeleidster dr. E. Huls bedanken. Haar heldere advies en aanstekelijke enthousiasme hebben deze thesis zonder twijfel tot een betere gemaakt. Ik ben in het bijzonder dankbaar en vereerd dat zij dit onderzoek namens ons beiden heeft gepresenteerd op het 17 e Sociolinguistics Symposium (Huls & Varwijk, 2008). Dank gaat ook uit naar Peter Varwijk voor het kritisch doornemen en beoordelen van het manuscript. Het commentaar heeft de leesbaarheid van de scriptie aanzienlijk vergroot. Miriam Lauwers heeft als tweede codeur een belangrijke bijdrage geleverd aan de betrouw- baarheid van het onderzoek. Veel dank hiervoor. Tot slot wil ik mijn vriendin Marieke bedanken voor haar onvoorwaardelijke steun en engelengeduld. Ik hoop ten zeerste dat deze thesis van waarde is in de huidige discus- sie over de neutraliteit van de Nederlandse media en dat die discussie in de toekomst een meer empirische inslag krijgt. -

Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2011 Waar Visie Ontbreekt, Komt

Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2011 Waar visie ontbreekt, komt het volk om Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2011 Waar visie ontbreekt, komt het volk om Redactie: Carla van Baalen Hans Goslinga Alexander van Kessel Johan van Merriënboer Jan Ramakers Jouke Turpijn Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Boom – Amsterdam Foto omslag: Paul Babeliowsky / Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Vormgeving: Boekhorst Design B.V., Culemborg © 2011 Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Behoudens de in of krachtens de Auteurswet van 1912 gestelde uitzonderingen mag niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch door fotokopieën, opnamen of enig andere manier, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestem- ming van de uitgever. No part of this book may be reproduced in any way whatsoever without the written permission of the publisher. isbn 978 94 6105 546 0 nur 680 www.uitgeverijboom.nl Inhoud Ten geleide 9 Artikelen Henri Beunders, De terugkeer van de klassenstrijd. De angst van de visieloze burgerij 15 voor ‘de massa’ lijkt op die van rond 1900 Patrick van Schie, Ferm tegenspel aan ‘flauwekul’. De liberale politiek-filosofische 29 inbreng in het Nederlandse parlement: voor individuele vrijheid en evenwichtige volksinvloed Arie Oostlander, Aan Verhaal geen gebrek. Over de noodzaak van een betrouwbaar 41 kompas voor het cda Paul Kalma, Het sociaaldemocratisch program… en hoe het in de verdrukking kwam 53 Erie Tanja, ‘Dragers van beginselen.’ De parlementaire entree van Abraham Kuyper en 67 Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis Koen Vossen, Een Nieuw Groot Verhaal? Over de ideologie van lpf en pvv 77 Hans Goslinga en Marcel ten Hooven, ‘De vraag is of de democratie blijvend is.’ Interview 89 met J.L. -

Speech Mariëtte Hamer Ledencongres Partij Van De Arbeid Breda, 14-06-2008

Speech Mariëtte Hamer Ledencongres Partij van de Arbeid Breda, 14-06-2008 Gesproken woord geldt DE PVDA, JUIST IN DEZE TIJD Partijgenoten, laten we er niet om heen draaien. Als je naar de peilingen kijkt, dan worden we daar niet vrolijk van. Nu zegt het politieke handboek dat ik nu tegen u moet zeggen: “Ach peilingen, het zijn maar dagkoersen, trekt u zich er niets van aan!!” Maar ik hoop dat u inmiddels weet dat dat mijn stijl niet is. Maurice de Hond doet natuurlijk gewoon zijn werk. Maar waar ik de pest in heb, is het beeld dat achter die peilingen schuil gaat. - Ik baal van de beschuldigingen van kiezersbedrog en vermeend gedraai. - Ik baal van het beeld dat de PvdA onzichtbaar is. - Ik baal van het verhaal dat er een richtingenstrijd zou zijn. - Ik baal ervan dat noodzakelijke maatregelen soms onhandig in het nieuws komen. - En ik baal het meest van het beeld dat dit kabinet geen resultaten boekt. Partijgenoten, En het is erger dan dat. De Politiek in zijn geheel maakt een opgejaagde indruk. Politici lopen steeds meer achter de waan van de dag aan. En waarom gebeurt dit? - Omdat politici denken daarmee het vertrouwen van kiezers te herwinnen. - Omdat we in Den Haag denken dat kiezers op hol zijn geslagen. - En omdat we denken dat we achter hen aan moeten lopen met makkelijke verhalen. Partijgenoten, dat is een Haagse wedstrijd die we niet kunnen winnen. En het is wat mij betreft ook een wedstrijd met de verkeerde spelregels. - Bij die wedstrijd regeert namelijk de angst. - Bij die wedstrijd is regeringsdeelname een hinderlijke blessure. -

The Populist Temptation

May 2010 THE NETHERLANDS: THE POPULIST TEMPTATION Christophe DE VOOGD www.fondapol.org THE NETHERLANDS: THE POPULIST TEMPTATION Christophe DE VOOGD The Fondation pour l’innovation politique is a liberal, progressive and European foundation President: Nicolas Bazire Vice-president: Charles Beigbeder Chief Executive Officer: Dominique Reynié [email protected] General Secretary: Corinne Deloy [email protected] THE NETHERLANDS: THE POPULIST TEMPTATION Christophe DE VOOGD Lecturer in history at Sciences Po, author of Histoire des Pays-Bas des origines à nos jours (Fayard, 2003) Few European countries have seen their international image change as radically as the Netherlands in such a short space of time. As recently as 2000, the Dutch economy, boasting one of the highest rates of growth in the OECD, focused international attention on the virtues of the polder- model, a blend of cooperation and moderation between business leaders and trade unions in a constant search for compromise. On social issues, the Dutch “laboratory”, with its liberal penal climate, its acceptance of gay marriage, the re-opening of brothels, its permissive policies on drugs and the legalisation of euthanasia, inspired interest around the world. The perspective has changed enormously since the tragic events of 2002 and 2004, with the assassination of populist leader Pim Fortuyn and polemic filmmaker Theo Van Gogh, which brought the Netherlands face-to-face with the spectre of political violence, something that had previously been absolutely proscribed from national politics. Dutch society has also been beset by doubts about the continuation of its van- guard experiments – particularly in respect to drugs – and the increase in crime has prompted calls for limits to be placed on the sacrosanct principle of gedogen, or tolerance, in all areas. -

Cover EMD 2005 Netherlands.Qxd

Current Immigration Debates in Europe: A Publication of the European Migration Dialogue Jan Niessen, Yongmi Schibel and Cressida Thompson (eds.) The Netherlands Vera Marinelli Jan Niessen, Yongmi Schibel and Cressida Thompson (eds.) Current Immigration Debates in Europe: A Publication of the European Migration Dialogue The Netherlands Vera Marinelli for FORUM (Institut voor Multikulturele Ontwikkeling) With the support of the European Commission Directorate-General Justice, Freedom and Security September 2005 The Migration Policy Group (MPG) is an independent organisation committed to policy development on migration and mobility, and diversity and anti-discrimination by facilitating the exchange between stakeholders from all sectors of society, with the aim of contributing to innovative and effective responses to the challenges posed by migration and diversity. This report is part of a series of 16 country reports prepared as a product of the European Migration Dialogue (EMD). The EMD is a partnership of key civil society organisations dedicated to linking the national and European debates on immigration and integration. It is supported by the European Commission, Directorate-General Justice, Freedom and Security, under the INTI funding programme. The individual reports on Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, and the UK are available from MPG’s website, together with a preface and introduction. See Jan Niessen, Yongmi Schibel and Cressida Thompson (eds.), Current Immigration Debates in Europe: A Publication of the European Migration Dialogue, MPG/Brussels, September 2005, ISBN 2-930399-18-X. Brussels/Utrecht, September 2005 © Migration Policy Group The Netherlands Vera Marinelli1 1.