Pilot Project for the Treatment of Photogravures on Gampi Paper by Edward S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

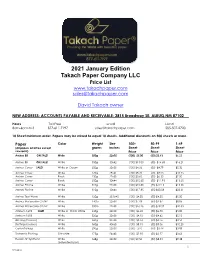

2021 January Edition Takach Paper Company LLC Price List [email protected]

2021 January Edition Takach Paper Company LLC Price List www.takachpaper.com [email protected] David Takach owner NEW ADDRESS: ACCOUNTS PAYABLE AND RECEIVABLE: 2815 Broadway SE. ALBUQ.NM 87102 Hours Toll Free email Local 8am-6pm M-S 877-611-7197 [email protected] 505-507-2720 10 Sheet minimum order. Papers may be mixed to equal 10 sheets. Additional discounts on 500 sheets or more. Paper Color Weight Size 100+ 50-99 1-49 (All papers acid free except grams inches Sheet Sheet Sheet newsprint) Price Price Price Arches 88 ON SALE! White 300g 22x30 (100) $5.00 (50) $5.63 $6.25 Arches 88 ON SALE! White 350g 30x42 (100) $13.05 (50) $14.68 $16.21 Arches Cover SALE! White or Cream 250g 22x30 (100) $4.26 (50) $4.79 $5.32 Arches Cover White 270g 29x41 (100) $8.20 (50) $9.23 $10.25 Arches Cover Black 250g 22x30 (100) $5.60 (50) $6.30 $7.00 Arches Cover Black 250g 30x44 (100) $10.60 (50) $11.93 $13.25 Arches Platine White 310g 22x30 (100) $10.80 (25) $12.15 $13.50 Arches Platine White 310g 30x44 (100) $17.85 (25) $20.08 $22.31 Arches Text Wove White 120g 25.5x40 (100) $4.00 (50) $4.50 $5.00 Arches Watercolor CP/HP White 140lb 22x30 (100) $7.08 (50) $7.87 $8.85 Arches Watercolor CP/HP White 300lb 22x30 (100) $16.26 (50) $18.07 $20.33 Arnhem 1618 SALE! White or Warm White 245g 22x30 (100) $2.40 (50) $2.70 $3.00 Arnhem 1618 White 320g 22x30 (100) $4.10 (50) $4.62 $5.13 Blotting (cosmos) White 360g 24x38 (100) $3.16 (50) $3.76 $3.50 Blotting (cosmos) White 360g 40x60 (100) $8.15 (50) $9.06 $10.20 Coventry Rag White 290g 22x30 (100) 3.10 (50) $3.44 -

2019 Catalog 12-14.Pdf

www.legionpaper.com www.moabpaper.com www.risingmuseumboard.com www.solvart.com © Copyright 2019 Legion Paper Corporation All Rights Reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced without the permission of Legion Paper. OUR ROMANCE WITH PAPER Peace treaties are signed on it. Declarations of love are written on it. Artists’ works are portrayed on it. Of course, we mean paper; the medium that has evolved to reflect its own poetry, becoming an opportunity for pure innovation and unlimited creativity. Through the years, a melding of ancient craft and enlightened technology occurred, creating new practices and opening new horizons for expression in paper. When we trace its history, we find insight into man’s relentless imagination and creativity. Today, this convergence of ancient and modern continues and paper emerges with not only greater variety but a renewed appreciation of quality. To some, fine paper is the space that translates what is conceived in the mind to what is authentic. To others, having access to the right paper represents abundant possibility and profitability. The very selection of paper now becomes an adventure, realizing how the end result will vary based upon choice. Today, as in the years past, Legion Paper continues to source the finest papermakers around the globe, respecting the skill of the artisan and the unique attributes of the finished product. As we head into the future, Legion remains steadfast in its commitment to diversity, customer service and an unparalleled level of professionalism. We’re sure you will want to touch and feel some of the 3,500 papers described on the following pages. -

Museum of Economic Botany, Kew. Specimens Distributed 1901 - 1990

Museum of Economic Botany, Kew. Specimens distributed 1901 - 1990 Page 1 - https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/57407494 15 July 1901 Dr T Johnson FLS, Science and Art Museum, Dublin Two cases containing the following:- Ackd 20.7.01 1. Wood of Chloroxylon swietenia, Godaveri (2 pieces) Paris Exibition 1900 2. Wood of Chloroxylon swietenia, Godaveri (2 pieces) Paris Exibition 1900 3. Wood of Melia indica, Anantapur, Paris Exhibition 1900 4. Wood of Anogeissus acuminata, Ganjam, Paris Exhibition 1900 5. Wood of Xylia dolabriformis, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 6. Wood of Pterocarpus Marsupium, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 7. Wood of Lagerstremia parviflora, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 8. Wood of Anogeissus latifolia , Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 9. Wood of Gyrocarpus jacquini, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 10. Wood of Acrocarpus fraxinifolium, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 11. Wood of Ulmus integrifolia, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 12. Wood of Phyllanthus emblica, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 13. Wood of Adina cordifolia, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 14. Wood of Melia indica, Anantapur, Paris Exhibition 1900 15. Wood of Cedrela toona, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 16. Wood of Premna bengalensis, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 17. Wood of Artocarpus chaplasha, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 18. Wood of Artocarpus integrifolia, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 19. Wood of Ulmus wallichiana, N. India, Paris Exhibition 1900 20. Wood of Diospyros kurzii , India, Paris Exhibition 1900 21. Wood of Hardwickia binata, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 22. Flowers of Heterotheca inuloides, Mexico, Paris Exhibition 1900 23. Leaves of Datura Stramonium, Paris Exhibition 1900 24. Plant of Mentha viridis, Paris Exhibition 1900 25. Plant of Monsonia ovata, S. -

C:\Data\WP\F\200\Catalogue Sections\Aaapreliminary Pages.Wpd

Jonathan A. Hill, Bookseller, Inc. 325 West End Avenue, Apt. 10B New York City, New York, 10023-8145 Tel: 646 827-0724 Fax: 212 496-9182 E-mail: [email protected] Catalogue 200 Proofs Science, Medicine, Natural History, Bibliography, & Much More Introduction & Selective Subject Index on Following Pages Introduction TWO HUNDRED CATALOGUES in thirty-three years: more than 35,000 books and manuscripts have been described in these catalogues. Thousands of other books, including many of the most important and unusual, never found their way into my catalogues, having been quickly sold before their descriptions could appear in print. In the last fifteen years, since my Catalogue 100 appeared, many truly exceptional books passed through my hands. Of these, I would like to mention three. The first, sold in 2003 was a copy of the first edition in Latin of the Columbus Letter of 1493. This is now in a private collection. In 2004, I was offered a book which I scarcely dreamed of owning: the Narratio Prima of Rheticus, printed in 1540. Presenting the first announcement of the heliocentric system of Copernicus, this copy in now in the Linda Hall Library in Kansas City, Missouri. Both of the books were sold before they could appear in my catalogues. Finally, the third book is an absolutely miraculous uncut copy in the original limp board wallet binding of Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius of 1610. Appearing in my Catalogue 178, this copy was acquired by the Library of Congress. This is the first and, probably the last, “personal” catalogue I will prepare. -

Preferred Source Application Requests

PREFERRED SOURCE APPLICATIONS APPROVED BY OGS AUGUST 2010 THROUGH OCTOBER 2010 Total Total OGS PSG Direct Disabled/ ESD Request Annual Sales Labor Blind Approval Control Number Commodity Type Customer Volume Workshop FTE's FTE's Date 823 Personal Protection Spray New Statewide $40,398.00 Herkimer Area ARC .07 .07 8/23/10 828 HIV Rapid Test Kits New Statewide $200,000.00 Maryhaven Center of Hope .447 .383 8/5/10 Diesel Exhaust Fluid 832 275 and 330 gallon tote New Statewide $200,000.00 Liberty Enterprises Inc .2345 .1759 9/29/10 Diesel Exhaust Fluid 833 55 gallon drum New Statewide $30,000.00 Liberty Enterprises Inc .1614 .1210 9/29/10 835 Thermal Paper Rolls New Statewide $84,000.00 ARC Oneida Lewis .1097 .1036 10/8/10 Description for My®Clyns Personal Protection Spray My®Clyns Personal Protection Spray represents a new category of product that is intended to be used following exposure to bodily fluids or other materials potentially containing harmful pathogens. It is the only non-alcohol option you can keep in your pocket and spray directly into your face, eyes, ears, nose, mouth and open wounds. It is ready to use in the field when you need effective protection right away. This commodity is provided by Herkimer Area ARC and will be available to all State Agencies. Work for the disabled includes receiving packaging, removing individual units and transferring to an assembly line, assemble shipping box, fill box with 12 units, close box and tape shut, apply shipping label and load pallet with finished product. -

Title Historical Value of Parabaik and Pei All Authors Moe Moe Oo Publication Type Local Publication Publisher (Journal Name, Is

Title Historical Value of Parabaik and Pei All Authors Moe Moe Oo Publication Type Local Publication Publisher (Journal name, Meiktila University, Research Journal, Vol.IV, No.1, 2013 issue no., page no etc.) Parabaiks and Palm Leaf Manuscripts are important in the rich and old tradition and cultural history of Southeast Asia. Many documents reflected the socio- economic situation and Buddhist text of ancient Myanmar. These sources are Abstract like a treasure-trove for historians. We hope that this Parabaik and Palm leaf will advance the study of the early modern history of Myanmar, as well as that of the whole Southeast Asian region, and will also contribute to the preservation of a valuable cultural heritage in Myanmar. cultural heritage, preservation Keywords Citation Issue Date 2013 61 Meiktila University, Research Journal, Vol.IV, No.1, 2013 Historical Value of Parabaik and Pei Moe Moe Oo1 Abstract Parabaiks and Palm Leaf Manuscripts are important in the rich and old tradition and cultural history of Southeast Asia. Many documents reflected the socio-economic situation and Buddhist text of ancient Myanmar. These sources are like a treasure-trove for historians. We hope that this Parabaik and Palm leaf will advance the study of the early modern history of Myanmar, as well as that of the whole Southeast Asian region, and will also contribute to the preservation of a valuable cultural heritage in Myanmar. Key Words: cultural heritage, preservation Introduction Myanmar Manuscripts are an attempt to deal with the socio- economic life of the people during the Kon-baung period. There are many books both published and unpublished in the forms of research journal and thesis. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Secondary Fiber Recycling 01993 TAPPI PRESS Atlanta. Georgia iii Preface v List of Contributors vii Table of Contents ix List of Figures and Tables Chapter 1 Recovered Paper and the U.S. Solid Waste Dilemma I 1 by Rodney Young Introduction and Overview ............................................ 1 Paper Industry Response to the Solid Waste Issue ................................ 2 U.S. Recovered Paper Consumption ..................................... 2 U.S. Trade in Recovered Paper ........................................ 3 U.S. Recovered Paper Recovery ....................................... 3 Recovered Paper Supply and Cost ...................................... 3 Bibliography .................................................... 4 Resources ................................................... 4 Chapter 2 Recycled- Versus Virgin-Fiber Characteristics: A Comparison 1 7 by R. L. Ellls and K. M. Ssdlachsk Introduction ..................................................... 7 Literature Review ................................................. 8 General Effect of Recycling ......................................... 8 Effect of Furnish .............................................. 10 Effect of initial Beating of Virgin Pulp ................................... 10 Theory for Tensile Strength of Paper .................................... 10 First Assumption ............................................ 11 Second Assumption .......................................... 12 Theory Verification ............................................ -

Evaluation of Conservation Quality Eastern Papers Regarding Materials and Process

Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8–10 April 2015 https://icon.org.uk/node/4998 Evaluation of conservation quality Eastern papers regarding materials and process Minah Song Copyright information: This article is published by Icon on an Open Access basis under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (CC BY-NC-ND) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. You are free to copy and redistribute this material in any medium or format under the following terms: You must give appropriate credit and provide a link to the license (you may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way which suggests that Icon endorses you or your use); you may not use the material for commercial purposes; and if you remix, transform, or build upon the material you may not distribute the modified material without prior consent of the copyright holder. You must not detach this page. To cite this article: Minah Song, ‘Evaluation of conservation quality Eastern papers regarding materials and process’ in Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8–10 April 2015 (London, The Institute of Conservation: 2017), 137–48. Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8-10 April 2015 137 Minah Song Evaluation of conservation quality Eastern papers regarding materials and process Introduction When conservators try to find a specific type of Eastern paper for a certain project, they think about visual specifications, permanence and durability, and, of course, about the price. -

Ref. 676.03 SMO 2Nd

INDEX Refer to Chapter Refer to Chapter Refer to Chapter A test 14 acid pretreatment 10 acetate 4 acidproof brick 8 abaca 3 acetate laminating 18 acid pulping 8 abatement 20 acetate pulp 4 acid rain 21 odor 21 acetic acid 4 acid-refined tall oil 6 pollution 20 acetic anhydride 4 acid-resistant 14 abatement device 21 acetone 4 acid size 5 abietic acid 6 acetylated starch 5 acid-stable size 5 abrasion 24 acetyl radical 4 acid sulfite process 8 abrasion debarker I acetylating agent 4 acid tower 8 abrasion resistance 14 acid(s) 4, 8 acid treatment 10 abrasion test 14 abietic 6 acidulating 4 abrasive 7 acetic 4 acidulating agent 4 abrasive backing papers 16 accumulator 8 acidulation 6 abrasiveness 14 carbonic 20 acoustical board 16 abrasive segment 7 Caro's 10 acoustical testing 14 abrasivity (of mineral fillers) 13 cooking 8 acoustic leak detector 9 absorbency 11,14 digester 8 acre-foot 20 relative II fatty 6 acrylamide resins 5 water II formamidine sulfinic 10 acrylic binders 17 absorbent 14,24 formic 4 acrylic fiber 3 absorbent capacity II glucuronic 4 activatable chemical 9 absorbent grades 16 humic 20 activated carbon 20 absorption 5 hydroxy 4 activated sludge 20 capillary 13 hypochlorous 10 activated sludge loading 20 ink 14 lignosulfonic 8 activated sludge process 20 light 14 linoleic 6 activation 4 mechanical 13 mineral 4 surface II tensile energy 14 oleic 6 activation energy 8 vapor 13 pectic 4 Arrhenius 4 absorption coefficient 14 peracetic 10 activator 5 accelerated aging 14 raw 8 active alkali 8 accelerated aging test 14 resin -

Cyanotype Process

CHAPTER 7 THE CYANOTYPE PROCESS ! Fig 7-1 here, (Christopher James, Foot of the Pyramid, 1994- toned cyanotype) OVERVIEW & EXPECTATIONS The cyanotype, or Ferro-Prussiate Process, is often the first technique that any of us learn in alternative process photography. Cyanotype is the proverbial “first kiss” that sinks the hook and makes us fall in love with all of the possibilities to come with alternative process image making… in much the same way that the wet lab darkroom experience did to all of the image makers who had the pleasure of that experience. The primary reason for this affection is the absolute simplicity of the process and chemistry, and the nearly fail-safe workflow. This is the process that is ideal for both © Christopher James, The Book of Alternative Photographic Processes: 3rd Edition, 2014 student and teacher alike as the opportunity of making a great print, and experiencing success the first time it is taught or attempted, is very high. As an example, I always begin a class or workshop with a 9’ x 18’ cyanotype mural on pre-sensitized fabric. This bonds a class and facilitates the student’s experience in making a beautiful giant size mural with nothing more than a piece of prepared cotton fabric, sunlight, themselves as the subject, a hose, an ocean, a stream or plastic trash can filled with water, and a dash of hydrogen peroxide for a cheap thrill finish. In the Cyanotype Variations chapter I will give you a step-by-step guide for making this project work as a class or for a family gathering at the beach. -

A Guide to Japanese Papermaking

A Guide To Japanese Papermaking Making Japanese Paper in the Western World Donald Farnsworth 3rd Edition A Guide To Japanese Papermaking Making Japanese Paper in the Western World Donald Farnsworth 3rd edition ISBN: 978-0-9799164-8-9 © 1989, 1997, 2018 Donald S. Farnsworth English translations © 1948 Charles E. Hamilton MAGNOLIA EDITIONS 2527 Magnolia St, Oakland CA 94607 Published by Magnolia Editions, Inc. www.magnoliapaper.com Table of Contents Author’s Preface 1 (Kunisaki Jihei, 1798; trans. Charles E. Hamilton, 1948) Introduction 3 Equipment (contemporary) 8 Cooking 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Bleaching 27 I. Sunlight Bleaching (ultraviolet light) 28 Japanese text by Kunisaki Jihei and woodcut illustrations by Seich- II. Hydrogen Peroxide Bleaching 29 uan Tōkei are reproduced from a 1925 edition of Kamisuki chōhōki III. Chlorine Bleaching 30 (A Handy Guide to Papermaking), first published in 1798. Beating 31 Charles E. Hamilton's translations are reproduced from the 1948 Pigmenting 37 English language edition of A Handy Guide to Papermaking pub- Dyeing 39 lished by the Book Arts Club, University of California, Berkeley. Formation Aid 45 With the 1948 edition now out of print and increasingly difficult Mixing Formation aid powder PMP 46 to find, I hope to honor Mr. Hamilton's efforts by bringing his thoughtful and savvy translations to a broader audience. His trans- Contemporary vat, wooden stirring comb... 48 lations appear italicized and circumscribed in the following text. Sheet Formation 51 I. Japanese: Su and Keta 54 I would like to acknowledge Mr. Fujimori-san of Awagami Paper II. Pouring Method 59 and his employees, Mr. Yoshida-san and his employees, for fur- thering my understanding of Japanese papermaking. -

Handmade Gampi

Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................ 2 About Us & Ordering Terms ............................................ 3 History of Washi ................................................................ 4 Japanese Papermaking .................................................... 5 Differences Between Washi and Western Paper ................... 7 Where our Washi Comes From ...................................... 8 Paper Specifications ........................................................ 11 Pricelist ............................................................................... 16 Fine Art and Conservation Handmade Papers ............................................. 20 Machinemade Papers ....................................... 26 Gampi Papers ..................................................... 29 Large Size Papers .............................................. 31 Small Size/ Specialty Papers .......................... 34 Rolls 100% Kozo Rolls ................................................ 36 Kozo Mix Rolls ................................................... 38 100% Sulphite Pulp Rolls ................................. 38 Inkjet Coated Rolls ........................................... 39 Gampi Rolls ........................................................ 39 Rayon Rolls ......................................................... 40 Decorative Rolls ................................................ 40 Decorative ........................................................................