Hunting Trips in Northern Rhodesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"D" PLATINUM CONTRACTING SERVICES, LLC #THATZWHY LLC (2Nd) Second Chance for All (H.E.L.P) Helping Earth Loving People (Ieec) - FELMA.Inc 1 Campus Road Ventures L.L.C

Entity Name "D" PLATINUM CONTRACTING SERVICES, LLC #THATZWHY LLC (2nd) Second Chance for All (H.E.L.P) Helping Earth Loving People (ieec) - FELMA.Inc 1 Campus Road Ventures L.L.C. 1 Love Auto Transport, LLC 1 P STREET NW LLC 1 Vision, INC 1,000 Days 10 FLORIDA AVE DDR LLC 10 Friends L.L.C. 100 EYE STREET ACQUISITION LLC 100 REPORTERS 100,000 Strong Foundation (The) 1000 CONNECTICUT MANAGER LLC 1000 CRANES LLC 1000 NEW JERSEY AVENUE, SE LLC 1000 VERMONT AVENUE SPE LLC 1001 CONNECTICUT LLC 1001 K INC. 1001 PENN LLC 1002 22ND STREET L.L.C. 1002 3RD STREET, SE LLC 1003 8TH STREET LLC 1005 E Street SE LLC 1008 Monroe Street NW Tenants Association of 2014 1009 NEW HAMPSHIRE LLC 101 41ST STREET, NE LLC 101 5TH ST, LLC 101 GALVESTON PLACE SW LLC 101 P STREET, SW LLC 101 PARK AVENUE PARTNERS, Inc. 1010 25th St 107 LLC 1010 25TH STREET LLC 1010 IRVING, LLC 1010 V LLC 1010 VERMONT AVENUE SPE LLC 1010 WISCONSIN LLC 1011 NEW HAMPSHIRE AVENUE LLC 1012 ADAMS LLC 1012 INC. 1013 E Street LLC 1013 U STREET LLC 1013-1015 KENILWORTH AVENUE LLC 1014 10th LLC 1015 15TH STREET, Inc. 1016 FIRST STREET LLC 1018 Florida Avenue Condominium LLC 102 O STREET, SW LLC 1020 16TH STREET, N.W. HOLDINGS LLC 1021 EUCLID ST NW LLC 1021 NEW JERSEY AVENUE LLC 1023 46th Street LLC 1025 POTOMAC STREET LLC 1025 VERMONT AVENUE, LLC 1026 Investments, LLC 1030 PARK RD LLC 1030 PERRY STREET LLC 1031 4TH STREET, LLC 1032 BLADENSBURG NE AMDC, LLC 104 O STREET, SW LLC 104 RHODE ISLAND AVENUE, N.W. -

Apéndices Del Libro “Las Dos Vidas Del Héroe”

LAS DOS VIDAS DEL HÉROE Digitalizado por “EL ARTE DE LOS BOSQUES” www.internet.com.uy/scoutuy/woodcraft Apéndices del libro “Las dos vidas del héroe” EL SCOUT MODELO DEL MUNDO por Nelson R. Block Editor de la “Revista Histórica del Escultismo” Baden-Powel nos dejó en “Roverismo hacia el Exito” una descripción de su versión de un Scout modelo: EL ROVER: UN HOMBRE DE LO PROFUNDO DEL BOSQUE Al escribir estas líneas, hay acampando en mi jardín un ejemplo vivo de lo que yo espero que, en amplia escala, sea el resultado de este libro. Así lo espero, con todo mi corazón. Es un Rover Scout de unos dieciocho años, que se está adiestrando para ser un hombre. Ha hecho una larga excursión con su morral a cuestas, en el que lleva una tienda liviana, su cobija, olla para cocinar y alimentos. Porta con él su hacha y una cuerda. Yen su mano un útil bordón con una cabeza tallada, hecha por él mismo. Además de esta carga, lleva consigo algo que es todavía más importante: una sonrisa feliz dibujada en su cara tostada por el clima. Anoche durmió con un viento y frío inclementes, a pesar de que le di a escoger dormir bajo techo. Simplemente observó, con una sonrisa, que habla sido un caluroso verano, y que un poco de viento frío era un cambio que seria provechoso. Es amante riel aire libre. Cocinó sus propios alimentos y se preparó un abrigo con todos los recursos de un viejo acampador.- Hoy ha estado mostrando a nuestros Scouts locales cómo utilizar el hacha con más efectividad, y les demostró que puede ensogar” un hombre, sin fallar, con su lazo. -

Rimes of Germany

THE RIMES OF GERMANY RESISTANCE (From (/1: Group by [ch on [he flrc dc 'I'n'amphe.) LONDON: THE FIELD & QUEEN (HORACE COX) LTD, BREAM'S BUILDXNGS. E.C. PRICE ONE SHILLING. 9: THE CRIMES OF GERMANY Being an Illustrated Synopsis of the violations of International Law and of Humanity by the armed forces of the German Empire. Based on the Official Enquiries of Great Britain, France, Russia and Belgium. With a Preface by Sir Theodore A. Cook. Being the Special Supplement issued by “ THE FIELD” NEWSPAPER revised and brought u P to date with extra illustrations. LONDON: Published by THE FIELD {9" QUEEN (HORACE COX), LTD., Bream's Buildings, EC‘ CONTENTS. PAGE 1 ~ man LIST OF CONTENTS. .. .. .. .. 3 (2) The Tradesman of Hamburg .. .. 49 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS (3) Aerschot .. .. .. ,. ,. 51 (4-) Andenne .. .. .. .. ‘, 51 PREFACE by Sm THEODORE Coox .. ,. 5 Chapter VIII.—CIVILIANS AS SCREENS. Chapter I.—CnI.\nzs AGAINST WOMEN AND (1) Evidence 0f Bryce Report " " 52 CHILDREN. (2) Evidence of Belgian Commission . 55 (l) Across the Frontier .. .. .. 13 , (2) The March to Paris .. .. .. 15 Chapter IX.—-SUMMARY 0F MURDERS .. 56 (3) HOfStadc ” ' “ " 16 (4) Louvain, Chapter X.-—KILLING AND MUTILATING Tm: Malines, Aerschot . 19 VVOUNDED. Chapter IL—OTHER CRIMES AGAINST WOMEN (1) Evidence of Bryce Commission ... A 57 AND CHILDREN TESTIFIED BY (2) French Official Reports . 59 GERMANS. ‘ (3) Belgian Official Reports . 63 (1) German Letters and Diaries 22 (4) German Admissions " " " 65 (2) Outrages and Murders m Belgium 23 Chapter XI.—RUSS!AN WOUNDED IN GERMAN HANDS . 69 Chapter III.—OUTRAGES AGAINST CIVILIANS. (1) French Official Reports . -

December 12, 2008

Book Catalog Sort - December 12, 2008 Artist/Maker Catalog # Key Descript Description SAHI 5083 ETHEL ROOSEVELT'S AUTOGRAPH BOOK-AUTOGRAPH BOOK PAPER ETHEL ROOSEVLET'S AUTOGRAPH BOOK WITH CARDS FROM W.T. GRANT, G. MARCONI & JOHN PHILIP SOUSA GOOD SAHI 6397 CARDBOARD SCRAPBOOK PAPER, LEATHER, CARDBOARD MAROON LEATHER BINDING & CORNERS ON FRONT & BACK COVERS.INTERIOR FRONT & BACK COVERS.INTER FRONT & BACK COVERS=BEIGE PAPER W/BROWN CROSSES ON A PENCILLED-IN GRID PATTERNS.CONTENTS + POOR, MOST PAGES ARE DETATCHED FROM BOOK, WEAK BINDING & TORN AT TOP SAHI 7632 Orange cover with textured floral and leaf pattern. There's also a diagonal with the words "Scrap Book" from the lower left to the upper right. On the binders scrap book is written in gold. Some of the newpaper clippings have been encapsulated and stored with it. Standard measurement: L 10 1/8, W 7 3/8, in. SAHI 7635 Rust color scrap book trimmed with red tape. Black writing: "Presented to: Mrs. E. C. Roosevelt Sr, By the Philippine Press Clipping Bureau, Incorporated, Manila, P. I." Standard measurement: L 13 1/2, W 8 7/8, in. SAHI 7645 Cloth cover frame. Painted brown, green, yellow and beige floral pattern. It's a book-like frame, inside are photos of a man with a goatee and a woman on the right side. Blue border with gold trim. Standard measurement: L 8, W 5 3/4, in. SAHI 7729 Photo album of the White House Restoration. Interior and exterior photos in a black leather bound album. The album is in a tan binder with a black label: "The White House Restoration." The front inside cover has Edith Roosevelt's book label. -

LIU Post, Special Collections, Brookville, NY 11548 the Franklin B. Lord Fishing and Hunting Collection Holdings List

LIU Post, Special Collections, Brookville, NY 11548 The Franklin B. Lord Fishing and Hunting Collection Holdings List Ackerman, Irving C. The wire-haired foxterrier. Text illustrations by Josephine Z. Rine, photographs by R. W. Tauskey. New York; G. Howard Watt. 1927 191 p. front., illus., plates, port. 22 cm Adams, Joseph. Salmon and trout angling: its theory, and practice on southern stream, torrent river, and mountain loch. By Joseph Adams "Corrigen"... with the forward The Marquess of Hartington With eighteen illustrations. New York; E. P. Dutton and company. 1923. 288 p. front., plates Aflalo, Frederick George, 1870-1918. A book of fishing stories edited by F. G. Aflalo with contributions by Lieut.-Col. P. R. Bairnsfather, R. Hon. Sydney G. Buxton, Lady Evelyn Cotterell, Lord Desborough (and others). London; J. M. Dent & Sons, ltd. New York; E. P. Dutton & co. ltd. 1913. 243 p. col. front., plates (part col.) Aflalo, Frederick George, 1870 - 1918. Fisherman's weather, by upwards of one hundred living anglers, edited by F.G. Aflalo. With eight full-page illustrations in color from paintings by Charles Whymper. London; A. & C. Black. 1906. xv, 256. 8 col. pl. (front.) Akerman, John Yonge, 1806-1873. Spring-tide; or, The angler and his friends. 2nd edition. London; R. Bentley. 1852. 2p. l., [iii]-xv. [1]. 192p. front. (port.) plates. 18 cm Alken, Henry Thomas, 1784-1851. The national sports of Great Britain. Fifty engravings with descriptions. A new edition. London; Methuen & co. 1903. [110] p. 50 col. pl. (incl. front.) Allan, Philip Bertram Murray, 1884 - Trout heresy. New York; Charles Scribner's sons. -

Patrick Mcgahern Books, Inc. Mcgahernbooks.Ca Order Line 613-230-2277 1

Patrick McGahern Books, Inc. mcgahernbooks.ca order line 613-230-2277 1. ALEXANDER, Kirkland B. The Log of the North Shore Club. Paddle and Portage on the Hundred Trout Rivers of Lake Superior. With 40 Illustrations. New York. G. P. Putnam's Sons. 1911. 12mo, 18cm, The First Edition, xvii,228p., in the original pebble grain blue cloth, gilt spine and cover titles with photo illustrations laid down on the upper cover framed in gilt border, some slight wear and some fade speckling on the cover photograph, else a very good sound copy 200.00 Bruns, 67. "The author complains that the Nepegon (still spelled with the E) is full of tourists. This when the big beautiful falls were still on the river, and when it produced it choicest and biggest squaretail (brook) trout such as the world's record of 14.5#. Very Scarce". (Bruns). "An interesting work". Wetzel. American Fishing Books, Bibliography, p96. Patrick McGahern Books, Inc. mcgahernbooks.ca order line 613-230-2277 A Classic on Big Game Hunting in British Columbia 2. BAILLIE-GROHMAN, W.A. Fifteen Years’ in the Hunting Grounds of Western America and British Columbia. With a chapter by Mrs Baillie-Grohman. London. Horace Cox. 1900. tall8vo, 24.5cm, The First Edition, xii,403,[2]p., (reviews), index, with a photogravure frontis portrait, and 77 plate illustrations, many text illustrations, 3 folded colour maps in rear pocket, in the original olive green linen, with gilt block decorated titles on the spine and upper cover, and floral black stamped decoration in the spine panels, bevelled boards, t.e.g., some fading at the outer and spine edges of the boards and on the inner dentelles, the laid paper endpapers are quite acidic, hinges shaken but holding, good to very good 400.00 Note. -

A Holmes and Doyle Bibliography

A Holmes and Doyle Bibliography Volume 2 Monographs and Serials By Subject Compiled by Timothy J. Johnson Minneapolis High Coffee Press 2010 A Holmes & Doyle Bibliography Volume 2, Monographs & Serials, by Subject This bibliography is a work in progress. It attempts to update Ronald B. De Waal’s comprehensive bibliography, The Universal Sherlock Holmes, but does not claim to be exhaustive in content. New works are continually discovered and added to this bibliography. Readers and researchers are invited to suggest additional content. The first volume in this supplement focuses on monographic and serial titles, arranged alphabetically by author or main entry. This second volume presents the exact same information arranged by subject. The subject headings used below are, for the most part, taken from the original De Waal bibliography. Some headings have been modified. Please use the bookmark function in your PDF reader to navigate through the document by subject categories. De Waal's major subject categories are: 1. The Sacred Writings 2. The Apocrypha 3. Manuscripts 4. Foreign Language Editions 5. The Literary Agent (Sir Arthur Conan Doyle) 6. The Writings About the Writings 7. Sherlockians and The Societies 8. Memorials and Memorabilia 9. Games, Puzzles and Quizzes 10. Actors, Performances and Recordings 11. Parodies, Pastiches, Burlesques, Travesties and Satires 12. Cartoons, Comics and Jokes The compiler wishes to thank Peter E. Blau, Don Hobbs, Leslie S. Klinger, and Fred Levin for their assistance in providing additional entries for this bibliography. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 01A SACRED WRITINGS -- INDIVIDUAL TALES -- A CASE OF IDENTITY (8) 1. Doyle, Arthur Conan. A Case of identity and other stories. -

SUBASTA 164– 20 OCTUBRE 2016 Libros De Caza

SUBASTA 164– 20 OCTUBRE 2016 Libros de caza 1 Ornitología. (Buliard, Pierre). Aviceptologie française, ou traité general de toutes les ruses dont on peut se servir puor prende les oiseaux qui sont en France. Avec une collection considérable de figures. Paris, chez J. Cussac, An III (1795). [1629]. 8º. XXIV+246+XLII p. Piel época, con tejuelo, y hierros dorados en el lomo. Exlibris G. Arrese. Tercera edición de este clásico de la caza de aves. Apareció por primera vez en 1778. Esta es la última edición publicada en el siglo XVIII y la primera póstuma. Pierre Bulliard (1752-1793), botánico francés y autor de numerosas publicaciones botánicas, es también el inventor del término "aviceptologie". Hay dos partes: la primera se refiere a las diferentes herramientas para el uso de los colectores, incluyendo señuelos de todas las especies de aves. El segundo se refiere trampas y arnés de caza. El tratado termina con un pequeño diccionario de términos utilizados por los atrapadores de aves. Salida: 70 € 2 Caza-Francia. Valle, Joseph la. La chasse a tir en France. Ouvrage illustre de 30 vignettes sur bois dessines par F. Grenier. París, Hachette, 1854. 8º. 2 h, 440 p, 2 h. Ilustraciones. Holandesa época. Cortes tintados. Exlibris de tampón. Salida: 160 € 3 Ornitología. Buliard. Aviceptologie française, ou traité general de toutes les ruses dont on peut se servir puor prende les oiseaux... Paris, Corbet, 1822. 8º. XXXII+386 p. 34 láminas. Holandesa de época. Cortes jaspeados. Puntos de óxido. R. Souhart, c.526. J. Thiebaud, c.140. Salida: 200 € 4 Caza-Perros. -

Case 20-31840-Sgj11 Doc 307 Filed 08/25/20 Entered 08/25/20 09:15:13 Page 1 of 83

Case 20-31840-sgj11 Doc 307 Filed 08/25/20 Entered 08/25/20 09:15:13 Page 1 of 83 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS In re: Chapter 11 TRIVASCULAR SALES LLC, et al.,1 Case No. 20-31840 (SGJ) Debtors. (Jointly Administered) AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE STATE OF CALIFORNIA } } ss.: COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES } Jorge Rodriguez, being duly sworn, deposes and says: 1. I am employed by Omni Agent Solutions, located at 5955 DeSoto Avenue, Suite 100, Woodland Hills, CA 91367. I am over the age of eighteen years and am not a party to the above-captioned action. 2. On August 10, 2020, I caused to be served the: a. On USB: Order (I) Approving The Disclosure Statement, (II) Establishing Procedures for Solicitation and Tabulation of Votes to Accept or Reject The Plan, (III) Approving the Form of Ballot and Solicitation Packages, (IV) Establishing the Voting Record Date, (V) Scheduling a Hearing for Confirmation of The Plan, and (VI) Granting Related Relief [Docket No. 206], (the “Order”), b. On USB: Debtors’ Second Amended Joint Plan of Reorganization Under Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code, (the “Plan”), c. On USB: Disclosure Statement for the Debtors’ Second Amended Joint Plan or Reorganization Under Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code, (the “Disclosure Statement”), d. Notice of Hearing to Consider of, and Deadline for Objecting to, the Debtors’ Joint Plan of Reorganization Under Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code, (the “Notice”), (2a through 2d collectively are referred to as the “Solicitation Package”) e. Solicitation Cover Letter, (the “Cover Letter”), f. -

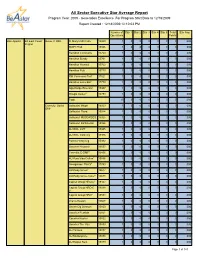

All Sector Executive Star Average Report Program Year: 2009 - Generation Excellence for Program Start Date to 12/18/2009 Report Created : 12/18/2009 12:10:03 PM

All Sector Executive Star Average Report Program Year: 2009 - Generation Excellence For Program Start Date to 12/18/2009 Report Created : 12/18/2009 12:10:03 PM Number of Star 1 Star 2 Star 3 Star 4 Star 5 Total Star Avg Operations Points Bon Appetit BA East Coast Bulau, P DMF St Mary's MD Cafe 15800 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Region MWPI Pratt 15806 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Hamilton Commons 15760 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Hamilton Bundy 15761 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Hamilton Howard 15762 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Hamilton Pub 15770 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 RW Commons-Res* 17521 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Hamilton Juice Bar* 17779 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Oglethorpe Emerson 15947 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Google Austell* 18793 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Total 10 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Connolly, David Gallaudet Mktplc 15923 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 DMF Gallaudet Plaza 15924 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Gallaudet MSSD/KDES 15925 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Gallaudet Rathskellar 15926 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 AU WCL CafT 15945 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 AU WCL Catering 15946 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Patrick Henry Clg 15982 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Goucher Heubeck 16557 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Connolly, D DMF* 16456 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 AU Pura Vida Coffee* 16886 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Georgetown Peet's* 17740 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 UoShady Grove* 18617 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 UoShady Grove Cater* 18678 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Capital Group HRO-C* 19337 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Capital Group HRO-C 19338 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 2* Capital Group HRO* 19558 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Oracle Reston 15608 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Gouch Clg Stimson 15850 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Goucher Pearlstn 15851 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 .000 Goucher -

This Digital Document Was Prepared for Cascade Historical Society By

This digital document was prepared for Cascade Historical Society by THE W. E. UPJOHN CENTER IS NOT LIABLE FOR COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT W.E. Upjohn Center for the Study of Geographical Change Department of Geography Western Michigan University 1100 Welborn Hall 269-387-3364 https://www.wmich.edu/geographicalchange [email protected] News Reporter Mrs. Ellyn BruinsSiot 676-1724 Please phone or send in your news as early as possible News Deadline Noon Monday Serving The Forest Hills Area VOLUME TEN- Nl)MBER FORTY THURSDAY, DECEMBER 17, 1964 NEWSSTAND COPY Sc Christmas parties set Special pastor's classes to begin PTA president killed for Ada-Thornapple Phone books at Eastmont Reformed Church On Tuesday, December 22, Thornapple School will have its Sunday, January 3, at 11 :20 rection just to prove to them, to be delivered 1n head-on collision Christmas party at about 2 p. m. a. m. a special pastor's class beyond any shadow of a doubt, will begin in the Eastmont Re that He was The One He claim Michigan Bell Telephone Com Donald G. Denison, jr., presi secretary-treasurer of the Grand The children will have a gift exchange not to exceed 50 cents. formed Church. This class is ed to be. He even made a spec pany starts delivery of new dent of the Parent-Teachers' Rapids Casting Company. A sail designed particularly for those ial trip to the upper room for Grand Rapids area telephone Association of Ada was killed ing enthusiast, he was a mem Ada will have its Christmas party the same day, but have who wish to inquire into the Thomas' sake so that Thomas directories on Thursday, Dec. -

An Annotated Bibliography of Books Related to Hunting the Wild Sheep and Goats of the World

An Annotated Bibliography of Books Related to Hunting the Wild Sheep and Goats of the World by Dr. Ken Czech Dr. Raul Valdez Safari Press Inc. Table Of Contents Acknowledgments.....................................................................vi Introduction.............................................................................vii Adair.to.Axbey...........................................................................1 Babala.to.Byroade....................................................................13 Caldwell.to.Cutting..............................................................36 Dalrymple.to.Durham............................................................53 Easton.to.Evans........................................................................63 Fawcett.to.Freeman.................................................................69 Gardner.to.Guillemard...........................................................77 Photo Section..........................................................................87 Haggard.to.Hutchinson.......................................................119 Imam.to.Irby......................................................................... 138 James.to.Judd..........................................................................140 Kahn.to.Kuntze.....................................................................145 Lacey.to.Lydekker..................................................................155 MacIntyre.to.Myers...............................................................165 Nazaroff.to.Nowicki.............................................................183