Some Thoughts on the Role of News and Current Affairs in Public Radio By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commission of Inquiry Into State Capture Held At

COMMISSION OF INQUIRY INTO STATE CAPTURE HELD AT PARKTOWN, JOHANNESBURG 10 10 SEPTEMBER 2019 DAY 160 20 10 SEPTEMBER 2019 – DAY 160 PROCEEDINGS COMMENCE ON 10 SEPTEMBER 2019 CHAIRPERSON: Good morning Ms Norman, good morning everybody. ADV THANDI NORMAN: Good morning Mr Chairperson. CHAIRPERSON: Yes are we ready? ADV THANDI NORMAN: Yes we are ready thank you Chair. CHAIRPERSON: Yes let us start. ADV THANDI NORMAN: Thank you Chair. Before you we have placed Exhibit CC31 for this witness. We are going to ask for a short adjournment after the testimony of this witness to put the relevant files 10 for the next witness Chair. CHAIRPERSON: Okay that is fine. ADV THANDI NORMAN: Thank you, yes thank you. Chair we are ready to lead the evidence of Mr Van Vuuren. May he be sworn in? His evidence continues from the DTT project as stated before the Chair by Ms Mokhobo and also Doctor Mothibi on Friday thank you. CHAIRPERSON: Yes okay. ADV THANDI NORMAN: Yes thank you. CHAIRPERSON: Please administer the oath or affirmation? REGISTRAR: Please state your full names for the record? 20 MR ANTON LOURENS JANSEN VAN VUUREN: Anton Lourens Janse Van Vuuren. REGISTRAR: Do you have any objection to taking the prescribed oath? MR ANTON LOURENS JANSEN VAN VUUREN: No. REGISTRAR: Do you consider the oath to be binding on your conscience? Page 2 of 174 10 SEPTEMBER 2019 – DAY 160 MR ANTON LOURENS JANSEN VAN VUUREN: Yes. REGISTRAR: Do you swear that the evidence you will give will be the truth; the whole truth and nothing but the truth, if so please raise your right hand and say, so help me God. -

South Africa's Anti-Corruption Bodies

Protecting the public or politically compromised? South Africa’s anti-corruption bodies Judith February The National Prosecuting Authority and the Public Protector were intended to operate in the interests of the law and good governance but have they, in fact, fulfilled this role? This report examines how the two institutions have operated in the country’s politically charged environment. With South Africa’s president given the authority to appoint key personnel, and with a political drive to do so, the two bodies have at times become embroiled in political intrigues and have been beholden to political interests. SOUTHERN AFRICA REPORT 31 | OCTOBER 2019 Key findings Historically, the National Prosecuting Authority The Public Protector’s office has fared (NPA) has had a tumultuous existence. somewhat better overall but its success The impulse to submit such an institution to ultimately depends on the calibre of the political control is strong. individual at its head. Its design – particularly the appointment Overall, the knock-on effect of process – makes this possible but might not in compromised political independence is itself have been a fatal flaw. that it is felt not only in the relationship between these institutions and outside Various presidents have seen the NPA and Public Protector as subordinate to forces, but within the institutions themselves and, as a result, have chosen themselves. leaders that they believe they could control to The Public Protector is currently the detriment of the institution. experiencing a crisis of public confidence. The selection of people with strong and This is because various courts, including visible political alignments made the danger of the Constitutional Court have found that politically inspired action almost inevitable. -

12-Politcsweb-Going-Off-The-Rails

http://www.politicsweb.co.za/documents/going-off-the-rails--irr Going off the rails - IRR John Kane-Berman - IRR | 02 November 2016 John Kane-Berman on the slide towards the lawless South African state GOING OFF THE RAILS: THE SLIDE TOWARDS THE LAWLESS SOUTH AFRICAN STATE SETTING THE SCENE South Africa is widely recognised as a lawless country. It is also a country run by a government which has itself become increasingly lawless. This is so despite all the commitments to legality set out in the Constitution. Not only is the post–apartheid South Africa founded upon the principle of legality, but courts whose independence is guaranteed are vested with the power to ensure that these principles are upheld. Prosecuting authorities are enjoined to exercise their functions “without fear, favour, or prejudice”. The same duty is laid upon other institutions established by the Constitution, among them the public protector and the auditor general. Everyone is endowed with the right to “equal protection and benefit of the law”. We are all also entitled to “administrative action that is lawful, reasonable, and procedurally fair”. Unlike the old South Africa – no doubt because of it – the new Rechtsstaat was one where the rule of law would be supreme, power would be limited, and the courts would have the final say. This edifice, and these ideals, are under threat. Lawlessness on the part of the state and those who run it is on the increase. The culprits run from the president down to clerks of the court, from directors general to immigration officials, from municipal managers to prison warders, from police generals to police constables, from cabinet ministers to petty bureaucrats. -

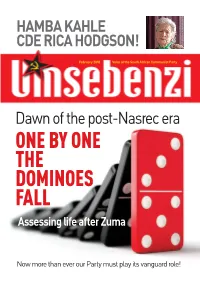

One by One the Dominoes Fall Assessing Life After Zuma

HAMBA KAHLE CDE RICA HODGSON! February 2018 Voice of the South African Communist Party Dawn of the post-Nasrec era ONE BY ONE THE DOMINOES FALL Assessing life after Zuma Now more than ever our Party must play its vanguard role! 2 Umsebenzi NEW YEAR Advancing into new, uncertain times As South Africa moves into exciting, but uncertain, times, writes Jeremy Cronin, our Party must be strategically consistent, analytically alert and tactically flexible enin is reputed to have once said on the matter (a report that somehow Mbeki… only to be re-hired and gifted “there are decades where nothing manages to leave the Guptas out of the with a fancy Dubai apartment when his happens, and weeks where decades equation). father’s fortunes turned. Lhappen.” It would be an exaggera- Yes, much of what is happening is still Over a year ago, the SACP called for tion to claim decades have been hap- half moves, reluctant shifts, or just the an independent judicial commission into pening in South Africa in the past few beginnings of long suppressed investiga- corporate capture of the state. The former weeks. We are not exactly living through tions. But we shouldn’t underestimate Public Protector, Thuli Madonsela’s State “ten days that shook the world” as John what is afoot, or fail to act vigorously in of Capture report took up this idea and Reed once described the 1917 Bolshevik support of the momentum that has now added that, since he was implicated in the Revolution. opened up. report, President Zuma could not select But we are certainly living through Everywhere, former Gupta political the judge. -

Accountability and the Role of Independent Constitutional Institutions in South Africa’S Post-Apartheid Constitutions

NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 60 Issue 1 Twenty Years of South African Constitutionalism: Constitutional Rights, Article 8 Judicial Independence and the Transition to Democracy January 2016 Accountability and the Role of Independent Constitutional Institutions in South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Constitutions HEINZ KLUG Professor of Law at the University of Wisconsin and an Honorary Senior Research Associate in the School of Law at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation HEINZ KLUG, Accountability and the Role of Independent Constitutional Institutions in South Africa’s Post- Apartheid Constitutions, 60 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. (2015-2016). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL LAW REVIEW VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 Heinz Klug Accountability and the Role of Independent Constitutional Institutions in South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Constitutions 60 N.Y.L. Sch. L. Rev. 153 (2015–2016) ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Heinz Klug is Evjue-Bascom Professor of Law at the University of Wisconsin and an Honorary Senior Research Associate in the School of Law at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. Part of this article was originally presented as a keynote address entitled “Poverty, Good Governance and Achieving the Constitution’s Promise,” at the Good Governance Conference in Pretoria, South Africa in October 2013. -

Lessons from the African Peer Review Mechanism

RESEARCH REPORT 17 Governance and APRM Programme August 2014 Getting Down to Business: Lessons from the African Peer Review Mechanism A look at the corporate governance thematic area in the Country Review Reports on Lesotho, Mauritius, Mozambique, South Africa, Tanzania and Zambia Terence Corrigan ABOUT SAIIA The South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA) has a long and proud record as South Africa’s premier research institute on international issues. It is an independent, non-government think tank whose key strategic objectives are to make effective input into public policy, and to encourage wider and more informed debate on international affairs, with particular emphasis on African issues and concerns. It is both a centre for research excellence and a home for stimulating public engagement. SAIIA’s research reports present in-depth, incisive analysis of critical issues in Africa and beyond. Core public policy research themes covered by SAIIA include good governance and democracy; economic policymaking; international security and peace; and new global challenges such as food security, global governance reform and the environment. Please consult our website www.saiia.org.za for further information about SAIIA’s work. ABOUT THE GOVERNA NCE A ND A PRM P ROGRA MME SAIIA’s Governance and African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) programme aims to place governance and African development at the centre of local and global discussions about the continent’s future. Its overall goal is to improve the ability of the APRM to contribute -

South Africa Country Report BTI 2018

BTI 2018 Country Report South Africa This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2018. It covers the period from February 1, 2015 to January 31, 2017. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2018 Country Report — South Africa. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2018. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2018 | South Africa 3 Key Indicators Population M 55.9 HDI 0.666 GDP p.c., PPP $ 13225 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 1.6 HDI rank of 188 119 Gini Index 63.4 Life expectancy years 61.9 UN Education Index 0.720 Poverty3 % 35.9 Urban population % 65.3 Gender inequality2 0.394 Aid per capita $ 25.8 Sources (as of October 2017): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2017 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2016. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary In the period under review, South Africa faced some of its most stringent economic-, social- and political challenges since its democratic transition in 1994. -

South Africa

BTI 2020 Country Report South Africa This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2020. It covers the period from February 1, 2017 to January 31, 2019. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of governance in 137 countries. More on the BTI at https://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2020 Country Report — South Africa. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2020. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2020 | South Africa 3 Key Indicators Population M 57.8 HDI 0.705 GDP p.c., PPP $ 13730 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 1.4 HDI rank of 189 113 Gini Index 63.0 Life expectancy years 63.5 UN Education Index 0.721 Poverty3 % 37.6 Urban population % 66.4 Gender inequality2 0.422 Aid per capita $ 17.8 Sources (as of December 2019): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2019 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2019. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary For close to a decade, South African democracy has been in a process of gradual decline. -

Public Protector Fearless Defender of Ethical Conduct – a Seven-Year Campaign

Public Protector Fearless defender of ethical conduct – A seven-year campaign C Thornhill School of Public Management and Administration University of Pretoria South Africa ABSTRACT An article entitled ‘The role of the Public Protector: case studies in public accountability’ was published by the author in the African Journal of Public Affairs, 4(2), September 2011. That article focused on some cases that illustrate the nature and extent of the role the Public Protector in identifying and making findings on significant cases of corrupt practices and maladministration. The current Public Protector, Advocate Thuli Madonsela, is now at the end of her seven-year non-renewable appointment. It is apposite to review her contribution to promoting ethical conduct and enforcing public accountability. A single article cannot do justice to all 150 reports produced during her term of office to prove the value of the Public Protector in the South African public sector. Instead, the article presents a desktop analysis of selected reports by the Public Protector, on cases involving the national, provincial and local spheres of government. The legislation relevant to the cases is discussed, in addition to the handling of the reports by the government and Parliament and the Constitutional Court’s ruling on the incumbent’s powers. The Nkandla case, also called Secure in comfort, epitomises the careful research, deliberation, findings and constitutional status of the Public Protector in the South African system of democratic government. INTRODUCTION Public administration and management consist of a number of functions that need to be performed to facilitate the delivery of services by public (and private) institutions. -

Political Identity Repertoires of South Africa's Professional Black Middle

POLITICAL IDENTITY REPERTOIRES OF SOUTH AFRICA’S PROFESSIONAL BLACK MIDDLE CLASS Amuzweni Lerato Ngoma University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg Supervisor: Professor Roger Southall Date: 14 September 2015 Declaration I declare that this report is my own unaided work. It is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any degree or examination in any other university. _ 28/09/2015 of date ii Dedication Kianga Nomalanga Oratilwe Ngoma, Kia, my princess, my angel. You who are Mother of the Sun. You who are sunrays. You, my baby, chosen and loved by God. Your light shines. I love you the mostest. Mommy. The Queen. iii Acknowledgements Thank you to the Konrad Adeneuar Foundation for financial support. I dedicate this to everyone who knows me! Special shout out to Roger my supervisor, Tshepo Ngoma my mom, Tumi Diseko and Tebogo Ngoma my fans and supporters. And not forgetting the vibrant black middle class participants in this study, you made me smarter and cracked me up! iv Abstract This study explored the socio-political capacity and agency of the professional Black middle class (BMC). It examined how Black professionals construct their professional and socio-political identities and the relationships therein. It finds that for the Black middle class race is a stronger identity marker than class, which affects its support and attitudes towards the African National Congress. Race, residence, intra-racial inequality function as the factors through which the BMC rejects a middle class identity. -

State of the Newsroom 2017 Fakers & Makers

State of the Newsroom 2017 Fakers & Makers A Wits Journalism Project Edited by Alan Finlay Lead researcher and editor: Alan Finlay Additional research: Odwa Mjo, Ntando Thukwana, Nomvelo Chalumbira Content advisory group: Lesley Cowling, Indra de Lanerolle, Bob Wekesa, Kevin Davie, Ruth Becker, Dinesh Balliah, Mathatha Tsedu For Wits Journalism: Professor Franz Krüger Photography: GroundUp Production, design and layout: Breyten and Bach Proofreading: Lizeka Mda External review: Ylva Rodny-Gumede Thanks to our donors and other contributors: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Fesmedia, The Press Council and the South African National Editors’ Forum. Cover photograph: Ashraf Hendricks/GroundUp (CC BY-ND 4.0). September 27, 2017. Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) regional secretary for the Western Cape, Tony Ehrenreich, addresses a crowd outside the provincial legislature. Thousands marched under the Cosatu banner in Cape Town calling for an end to state capture. Find full report at: www.journalism.co.za/stateofnewsroom CONTENTS ii. PREFACE Franz Krüger iii. INTRODUCTION Alan Finlay 1. THE NEWSROOM IN REVIEW: 2017 10. HOW REAL IS “FAKE NEWS” IN SOUTH AFRICA? Irwin Manoim and Admire Mare 21. GETTING THE STORY STRAIGHT: The take up of fact-checking journalism in South African newsrooms over the past five years Bob Wekesa, Blessing Vava and Hlabangani Mtshali 28. NEWSROOM SURVEY: 2017 Journalists in South Africa’s newsrooms: Who are they, what do they do and how are their roles changing? Alastair Otter and Laura Grant 48. APPENDICES 48. Comparable circulation of daily, weekly and weekend newspapers, Q3 2016 and 2017 50. Selected insights from the Broadcast Research Council’s Radio Audience Measurement (Nov 2017 release) 52. -

The Government As a Moral Agent in the Process of Moral Renewal in South Africa: a Christian Ethical Perspective

The Government as a moral agent in the process of moral renewal in South Africa: a Christian ethical perspective PT Masase 12604372 Thesis submitted for the degree Philosophiae Doctor in Ethics at the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University Supervisor: Prof dr JM Vorster May 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank the Almighty God through Jesus Christ who guided me through this study. God's grace is really amazing. My wife Livhuwani Bridget Masase, you are a pillar of strength; you are indeed a suitable helper for me. I dedicate this thesis to you. I thank my Promoter Prof Dr J.M Vorster for his insight and patience when he was guiding me through this study. Mr CHB Botha of Castello Boerdery you a kind hearted. To God be the glory. Thank you Sir, Oom Rudolf and Oom Karel Grissen for financial support. My spiritual father Prof Dr RS Letsosa and my spiritual mother Mrs MS Letsosa I appreciate your love and support particularly for believing in my gifts and potential. My biological father and mother who didn't have opportunity to go to school, this is for you. Nothing is impossible with God. All my five brothers, sister in law, mother in law and brother in law, thank you for believing in my gifts. Reformed Church Boskop, this must symbolise a monument of hope. Giving hope to the hopeless. If I can do it, everyone can do it. 2 ABSTRACT Title: The government as moral agent in the process of moral renewal in South Africa: A Christian ethical perspective Keywords: Moral decay, Moral renewal, moral regeneration, public morality, core moral issues, moral agent, role of the government, Christian ethical perspective, Constitutional perspective South African society relapsed into widespread moral decay.