South Africa Country Report BTI 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The South African Criminal Law's Response to The

THE SOUTH AFRICAN CRIMINAL LAW’S RESPONSE TO THE CRIMES OF FRAUD AND CORRUPTION WITHIN LOCAL GOVERNMENT by STEPHANIE NAIDOO Submitted in accordance with the requirements of the degree of MASTERS OF LAW (LLM) in the subject PUBLIC LAW at the UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR G.P. STEVENS OCTOBER 2016 © University of Pretoria ii DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA The Department of Public Law places great emphasis upon integrity and ethical conduct in the preparation of all written work submitted for academic evaluation. While academic staff teach you about referencing techniques and how to avoid plagiarism, you too have a responsibility in this regard. If you are at any stage uncertain as to what is required, you should speak to your lecturer before any written work is submitted. You are guilty of plagiarism if you copy something from another author’s work (eg a book, an article or a website) without acknowledging the source and pass it off as your own. In effect you are stealing something that belongs to someone else. This is not only the case when you copy work word-for-word (verbatim), but also when you submit someone else’s work in a slightly altered form (paraphrase) or use a line of argument without acknowledging it. You are not allowed to use work previously produced by another student. You are also not allowed to let anybody copy your work with the intention of passing if off as his/her work. Students who commit plagiarism will not be given any credit for plagiarised work. The matter may also be referred to the Disciplinary Committee (Students) for a ruling. -

Country Guide South Africa

Human Rights and Business Country Guide South Africa March 2015 Table of Contents How to Use this Guide .................................................................................. 3 Background & Context ................................................................................. 7 Rights Holders at Risk ........................................................................... 15 Rights Holders at Risk in the Workplace ..................................................... 15 Rights Holders at Risk in the Community ................................................... 25 Labour Standards ................................................................................. 35 Child Labour ............................................................................................... 35 Forced Labour ............................................................................................ 39 Occupational Health & Safety .................................................................... 42 Trade Unions .............................................................................................. 49 Working Conditions .................................................................................... 56 Community Impacts ............................................................................. 64 Environment ............................................................................................... 64 Land & Property ......................................................................................... 72 Revenue Transparency -

NATIONAL ORGANISING COMMITTEE Dear Comrades, Please Be Informed That Our Regional Leadership, Elected at the Various Congresses, -Is As Follows: 1

SOUTH AFRICAN COMMUNIST PARTY SOUTH AFRICAN COMMUNIST PARTY Central Committee November 28, 1991 TO : ALL REGIONS FROM : NATIONAL ORGANISING COMMITTEE Dear Comrades, Please be informed that our regional leadership, elected at the various congresses, -is as follows: 1. BORDER: (Regional Office: Bisho, 0401-951248) Matthew Makalima (Chairperson) Skenjana Roji (Secretary) Trevor Campbell (Tr asurer) Additional Members: Thobile Mseleni, Smuts Ngonyama. Boyce Soci, Ncumisa Kondlo, Busisiwe Dingaan, Mzwandile Masala, Bongi Zokwe, Victor Nyezi, Barend Schuitema, Andile Sishuba, Penrose Ntlonti, Vuyo Jack. 2. EASTERN CAPE: (Regional Office: P.E., 041-415106/411242) Mbulelo Goniwe (Chairperson) Duma Nxarhane (Deputy Chairperson) Mtiwabo Ndube (Secretary) Ngcola Hempe (Deputy Secretary) Gloria Barry (Treasurer) Additional Members: Mike Xego, Mncedisi Nontsele, Thembani Pantsi, Dorcas Runeli, Neela Hoosain, Fieldmore Langa, Pamela Yako, Michael Peyi, Phumla Nqakula, Skhumbuzo Tyibilika. 3. NATAL MIDLANDS: (Regional Office: PMB, 0331-945168) Dumisani Xulu (Chairperson) Ephraim Ngcobo (Deputy Chairperson) Dikobe Ben Martins (Secretary) Cassius Lubisi (Deputy Secretary) Phumelele Nzimande (Treasurer) Additional Members: Yunus Carrim, Blade Nzimande, Isaiah Ntshangase, Sbongile Mkhize, Bathabile Dlamini, Thulani Thungo, Maurice Zondi. -2 - 4. PWV: (Regional Office: Johannesburg, 011-8344556/8344657) Gwede Mantashe Chairperson) Bob Mabaso (Deputy Chairperson) Jabu Moleketi (Secretary) Trish Hanekom (Deputy Secretary) George Mukhari (Treasurer) Additional Members: Dipuo Mvelase, Stan Nkosi, Nomvula Mokonyane, Jerry Majatladi, Mandla Nkomfe, Trevor Fowler, So Tsotetsi, Musi Moss, Vusi Mavuso, Ignatius Jacobs. 5. SOUTHERN NATAL: (Regional Office: Durban, 031-3056186) Thami Mohlomi (Chairperson) Important Mkhize (Deputy Chairperson) Dennis Nkosi (Secretary) Nozizwe Madlala (Deputy Secretary) Dumisane Mgeyane (Treasurer) Additional Members: Siza Ntshakala, Mpho Scott, Thami Msimang, Fareed Abdahulla, Billy Nair, Yousuf Vawda, Norman Levy, Jonathan Gumbi, Eric Mtshali, Linford Mdibi. -

South Africa | Freedom House Page 1 of 8

South Africa | Freedom House Page 1 of 8 South Africa freedomhouse.org In May 2014, South Africa held national elections that were considered free and fair by domestic and international observers. However, there were growing concerns about a decline in prosecutorial independence, labor unrest, and political pressure on an otherwise robust media landscape. South Africa continued to be marked by high-profile corruption scandals, particularly surrounding allegations that had surfaced in 2013 that President Jacob Zuma had personally benefitted from state-funded renovations to his private homestead in Nkandla, KwaZulu-Natal. The ruling African National Congress (ANC) won in the 2014 elections with a slightly smaller vote share than in 2009. The newly formed Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), a populist splinter from the ANC Youth League, emerged as the third-largest party. The subsequent session of the National Assembly was more adversarial than previous iterations, including at least two instances when ANC leaders halted proceedings following EFF-led disruptions. Beginning in January, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU) led a five-month strike in the platinum sector, South Africa’s longest and most costly strike. The strike saw some violence and destruction of property, though less than AMCU strikes in 2012 and 2013. The year also saw continued infighting between rival trade unions. The labor unrest exacerbated the flagging of the nation’s economy and the high unemployment rate, which stood at approximately 25 percent nationally and around 36 percent for youth. Political Rights and Civil Liberties: Political Rights: 33 / 40 [Key] A. Electoral Process: 12 / 12 Elections for the 400-seat National Assembly (NA), the lower house of the bicameral Parliament, are determined by party-list proportional representation. -

Commission of Inquiry Into State Capture Held At

COMMISSION OF INQUIRY INTO STATE CAPTURE HELD AT PARKTOWN, JOHANNESBURG 10 10 SEPTEMBER 2019 DAY 160 20 10 SEPTEMBER 2019 – DAY 160 PROCEEDINGS COMMENCE ON 10 SEPTEMBER 2019 CHAIRPERSON: Good morning Ms Norman, good morning everybody. ADV THANDI NORMAN: Good morning Mr Chairperson. CHAIRPERSON: Yes are we ready? ADV THANDI NORMAN: Yes we are ready thank you Chair. CHAIRPERSON: Yes let us start. ADV THANDI NORMAN: Thank you Chair. Before you we have placed Exhibit CC31 for this witness. We are going to ask for a short adjournment after the testimony of this witness to put the relevant files 10 for the next witness Chair. CHAIRPERSON: Okay that is fine. ADV THANDI NORMAN: Thank you, yes thank you. Chair we are ready to lead the evidence of Mr Van Vuuren. May he be sworn in? His evidence continues from the DTT project as stated before the Chair by Ms Mokhobo and also Doctor Mothibi on Friday thank you. CHAIRPERSON: Yes okay. ADV THANDI NORMAN: Yes thank you. CHAIRPERSON: Please administer the oath or affirmation? REGISTRAR: Please state your full names for the record? 20 MR ANTON LOURENS JANSEN VAN VUUREN: Anton Lourens Janse Van Vuuren. REGISTRAR: Do you have any objection to taking the prescribed oath? MR ANTON LOURENS JANSEN VAN VUUREN: No. REGISTRAR: Do you consider the oath to be binding on your conscience? Page 2 of 174 10 SEPTEMBER 2019 – DAY 160 MR ANTON LOURENS JANSEN VAN VUUREN: Yes. REGISTRAR: Do you swear that the evidence you will give will be the truth; the whole truth and nothing but the truth, if so please raise your right hand and say, so help me God. -

South Africa's Anti-Corruption Bodies

Protecting the public or politically compromised? South Africa’s anti-corruption bodies Judith February The National Prosecuting Authority and the Public Protector were intended to operate in the interests of the law and good governance but have they, in fact, fulfilled this role? This report examines how the two institutions have operated in the country’s politically charged environment. With South Africa’s president given the authority to appoint key personnel, and with a political drive to do so, the two bodies have at times become embroiled in political intrigues and have been beholden to political interests. SOUTHERN AFRICA REPORT 31 | OCTOBER 2019 Key findings Historically, the National Prosecuting Authority The Public Protector’s office has fared (NPA) has had a tumultuous existence. somewhat better overall but its success The impulse to submit such an institution to ultimately depends on the calibre of the political control is strong. individual at its head. Its design – particularly the appointment Overall, the knock-on effect of process – makes this possible but might not in compromised political independence is itself have been a fatal flaw. that it is felt not only in the relationship between these institutions and outside Various presidents have seen the NPA and Public Protector as subordinate to forces, but within the institutions themselves and, as a result, have chosen themselves. leaders that they believe they could control to The Public Protector is currently the detriment of the institution. experiencing a crisis of public confidence. The selection of people with strong and This is because various courts, including visible political alignments made the danger of the Constitutional Court have found that politically inspired action almost inevitable. -

Introduction It Goes Without Saying, Comrades, That Organising Is a Very Crucial Element of the Machinery of the Party- Building Programme

Introduction It goes without saying, comrades, that organising is a very crucial element of the machinery of the Party- building programme. It is its engine and nuts and bolts. If we have not yet assembled our machine as we would have desired, bear in mind that the National Organising Committee was only formed in late August. Indeed, I am very new in this post, having been appointed convenor of the committee on August 26. Section 1 Party of a new type 1) VANGUARD MASS PARTY The question that confronted the Party immediately after its unbanning was: What kind of Party should we build? The question arose because its unbanning after 40 years underground meant the Party could exist and woik legally in South Africa. What had become clear even as we were still banned and working underground was that the Party continued to enjoy a lot of support from our people. In determining our work within the legal space offered us by the new political conditions in our motherland, we had to take into serious consideration the tremendous mass support accorded us. The decisions taken in the circumstances were: 1. That the Party be transformed to accommodate a large membership. 2. That it would still be possible for the Party, despite the large membership, to retain its vanguardist role. We felt it could be a vanguard party of a new type with all its members being activists. We felt also that this vanguard party of a new type had to be open to public scrutiny. We said the vanguard party had to be open to all questions from the masses in a new culture of open debate and discussion. -

Powers of the Public Protector: Are Its Findings and Recommendations Legally Binding?

POWERS OF THE PUBLIC PROTECTOR: ARE ITS FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS LEGALLY BINDING? by MOLEFHI SOLOMON PHOREGO 27312837 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree: Master of Laws (LLM Research): Public Law Study Leader: Professor Danie Brand Department of Public Law, University of Pretoria November 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………………….........................vii CHAPTER 1 Introduction…..…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..1 The Public Protector as a Chapter Nine Institution………………………………………………………1 Research problem………………………………………………………………………………………………………..2 Aims and objectives of study……………………………………………………………………………………….3 Research Methodology………………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Research Questions………………………………………………………………………………………………………4 Limitations…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 Chapter Outline……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 CHAPTER 2 CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS GOVERNING THE OPERATIONS OF THE OFFICE OF THE PUBLIC PROTECTOR Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 The Constitutional provisions……………………………………………………………………………………..7 Meaning of “Appropriate remedial action’ as contained in the Constitution….…………..11 STATUTORY PROVISIONS REGULATING THE OFFICE OF THE PUBLIC PROTECTOR……...10 Section 6 of the Public Protector Act………………………………………………………………………….12 i Section 7 of the Public Protector Act………………………………………………………………………….17 Section 8 of the Public Protector Act………………………………………………………………………….19 -

Reconfiguring the World System: Envisioning Inclusive Development Through a Socially Responsive Economy

News independentTHE SUNDAY 3 FEBRUARY 18 2018 Traditional style and cheerful KHOISAN activist and politi- cian from the Eastern Cape arrived on the red carpet at the State of the Nation address on Friday in Nkosazana Atraditional attire, so that President Dlamini Cyril Ramaphosa would not forget Zuma. the indigenous Khoisan peoples. PICTURE: Christian Martin, a member ELMOND of the Eastern Cape provincial JIYANE/GCIS legislature, was one of four Khoisan activists who made headlines in December Aaron Motsoaledi and Lethabo Motsoaledi. when they walked from the PICTURE: KOPANO TLAPE/ GCIS Eastern Cape and staged a live-in protest and hunger strike at the Union Build- ings in Pretoria. Their 24-day protest only ended after Rama- phosa came out to meet them where they had set up camp, but not before they garnered the atten- tion and support of thou- sands of members of the public. Martin joined others on the red carpet before the State of the Nation address, including ministers and their wives and partners such as David Mahlobo, Aaron Motsoaledi, Nko- sazana Dlamini Zuma, Nathi Mthethwa and Bheki Cele. Everyone seemed happy and cheerful as they posed for cameras, including Pub- lic Protector Busisiwe Mkh- webane, in a doll-like red dress. Western Cape Premier Helen Zille looked glam and fresh in a simple but styl- ish silky dress. – Staff Nathi Nhleko and Nomcebo Reporter/African News Bheki Cele and his wife Thembeka Minister Jeff Radebe and wife Bridgette Motsepe. Lindiwe Zulu and her daughter Phindile. Mthembu. Agency (ANA) PICTURE: KOPANO TLAPE/GCIS PICTURE: KOPANO TLAPE GCIS PICTURE: ELMOND JIYANE/ GCIS Ngcobo PICTURE: ELMOND JIYANE/GCIS FEATURE Reconfiguring the World System: Envisioning inclusive development through a socially responsive economy Ari Sitas peace and security, in innovations for development what Britain achieved between the 1790s and the s South Africa takes over the BRICS based on the fourth industrial revolution, in the 1890s. -

Africa's Best Read

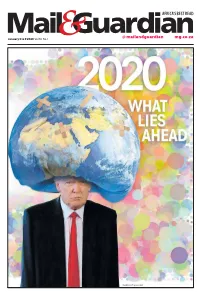

AFRICA’S BEST READ January 3 to 9 2020 Vol 36 No 1 @ mailandguardian mg.co.za Illustration: Francois Smit 2 Mail & Guardian January 3 to 9 2020 Act or witness IN BRIEF – THE NEWS YOU MIGHT HAVE MISSED Time called on Zulu king’s trust civilisation’s fall The end appears to be nigh for the Ingonyama Trust, which controls more than three million A decade ago, it seemed that the climate hectares of land in KwaZulu-Natal on behalf crisis was something to be talked about of King Goodwill Zwelithini, after the govern- in the future tense: a problem for the next ment announced it will accept the recommen- generation. dations of the presidential high-level panel on The science was settled on what was land reform to review the trust’s operations or causing the world to heat — human emis- repeal the legislation. sions of greenhouse gases. That impact Minister of Agriculture, Land Reform and had also been largely sketched out. More Rural Development Thoko Didiza announced heat, less predictable rain and a collapse the decision to accept the recommendations in the ecosystems that support life and and deal with barriers to land ownership human activities such as agriculture. on land controlled by amakhosi as part of a But politicians had failed to join the dots package of reforms concerned with rural land and take action. In 2009, international cli- tenure. mate negotiations in Copenhagen failed. She said rural land tenure was an “immedi- Other events regarded as more important ate” challenge which “must be addressed.” were happening. -

Quarterly Activities Report for the Period Ending 31

QUARTERLY ACTIVITIES REPORT FOR THE 30 Apr 2018 PERIOD ENDING 31 MARCH 2018 Board of Directors: Michael Fry HIGHLIGHTS (Non-executive Chairman) Robert Willes • Vice President and President of the ANC Cyril (Managing Director) Ramaphosa elected as President of South Africa, representing a major change in power. William Bloking (Non-executive Director) • Gwede Mantashe, the former Secretary General of the ANC, appointed as the Minister of Mineral Issued capital: Resources. 389,466,818 fully paid • Select Committee currently deliberating the ordinary shares (ASX: CEL) proposed amendments to the Bill submitted during the public participation process. 53,250,000 unlisted options and rights • Given past delays and remaining uncertainties around the timing of exploration rights awards, the Company continues to focus on internal cost Substantial holders: control and is actively pursuing other LQ Super 11.06% opportunities that could add a further dimension to the Company’s portfolio. W&M Brown 7.47% Registered office: Level 17, 500 Collins St Melbourne VICTORIA 3000 Tel +61 3 9614 0600 Fax +61 3 9614 0550 Changing Political Landscape In December 2017, Vice President Cyril Ramaphosa was elected as the President of South Africa’s governing political party, the African National Congress (“ANC”). In February 2018, he was elected President of South Africa in a parliamentary vote following the resignation of Jacob Zuma. This represents a major change in power with key changes in cabinet announced on 26 February 2018, most notably: 1. The Minister of Finance (formerly Malusi Gigaba, now Nhlanhla Nene); 2. The Minister of Mineral Resources (formerly Mosebenzi Zwani, now Gwede Mantashe, former Secretary General of the ANC); and 3. -

The New Cabinet

Response May 30th 2019 The New Cabinet President Cyril Ramaphosa’s cabinet contains quite a number of bold and unexpected appointments, and he has certainly shifted the balance in favour of female and younger politicians. At the same time, a large number of mediocre ministers have survived, or been moved sideways, while some of the most experienced ones have been discarded. It is significant that the head of the ANC Women’s League, Bathabile Dlamini, has been left out – the fact that her powerful position within the party was not enough to keep her in cabinet may be indicative of the President’s growing strength. She joins another Zuma loyalist, Nomvula Mokonyane, on the sidelines, but other strong Zuma supporters have survived. Lindiwe Zulu, for example, achieved nothing of note in five years as Minister of Small Business Development, but has now been given the crucial portfolio of social development; and Nathi Mthethwa has been given sports in addition to arts and culture. The inclusion of Patricia de Lille was unforeseen, and it will be fascinating to see how, as one of the more outspokenly critical opposition figures, she works within the framework of shared cabinet responsibility. Ms de Lille has shown herself willing to change parties on a regular basis and this appointment may presage her absorbtion into the ANC. On the other hand, it may also signal an intention to experiment with a more inclusive model of government, reminiscent of the ‘government of national unity’ that Nelson Mandela favoured. During her time as Mayor of Cape Town Ms de Lille emphasised issues of spatial planning and land-use, and this may have prompted Mr Ramaphosa to entrust her with management of the Department of Public Works’ massive land and property holdings.