Public Protector Fearless Defender of Ethical Conduct – a Seven-Year Campaign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commission of Inquiry Into State Capture Held At

COMMISSION OF INQUIRY INTO STATE CAPTURE HELD AT PARKTOWN, JOHANNESBURG 10 10 SEPTEMBER 2019 DAY 160 20 10 SEPTEMBER 2019 – DAY 160 PROCEEDINGS COMMENCE ON 10 SEPTEMBER 2019 CHAIRPERSON: Good morning Ms Norman, good morning everybody. ADV THANDI NORMAN: Good morning Mr Chairperson. CHAIRPERSON: Yes are we ready? ADV THANDI NORMAN: Yes we are ready thank you Chair. CHAIRPERSON: Yes let us start. ADV THANDI NORMAN: Thank you Chair. Before you we have placed Exhibit CC31 for this witness. We are going to ask for a short adjournment after the testimony of this witness to put the relevant files 10 for the next witness Chair. CHAIRPERSON: Okay that is fine. ADV THANDI NORMAN: Thank you, yes thank you. Chair we are ready to lead the evidence of Mr Van Vuuren. May he be sworn in? His evidence continues from the DTT project as stated before the Chair by Ms Mokhobo and also Doctor Mothibi on Friday thank you. CHAIRPERSON: Yes okay. ADV THANDI NORMAN: Yes thank you. CHAIRPERSON: Please administer the oath or affirmation? REGISTRAR: Please state your full names for the record? 20 MR ANTON LOURENS JANSEN VAN VUUREN: Anton Lourens Janse Van Vuuren. REGISTRAR: Do you have any objection to taking the prescribed oath? MR ANTON LOURENS JANSEN VAN VUUREN: No. REGISTRAR: Do you consider the oath to be binding on your conscience? Page 2 of 174 10 SEPTEMBER 2019 – DAY 160 MR ANTON LOURENS JANSEN VAN VUUREN: Yes. REGISTRAR: Do you swear that the evidence you will give will be the truth; the whole truth and nothing but the truth, if so please raise your right hand and say, so help me God. -

South Africa's Anti-Corruption Bodies

Protecting the public or politically compromised? South Africa’s anti-corruption bodies Judith February The National Prosecuting Authority and the Public Protector were intended to operate in the interests of the law and good governance but have they, in fact, fulfilled this role? This report examines how the two institutions have operated in the country’s politically charged environment. With South Africa’s president given the authority to appoint key personnel, and with a political drive to do so, the two bodies have at times become embroiled in political intrigues and have been beholden to political interests. SOUTHERN AFRICA REPORT 31 | OCTOBER 2019 Key findings Historically, the National Prosecuting Authority The Public Protector’s office has fared (NPA) has had a tumultuous existence. somewhat better overall but its success The impulse to submit such an institution to ultimately depends on the calibre of the political control is strong. individual at its head. Its design – particularly the appointment Overall, the knock-on effect of process – makes this possible but might not in compromised political independence is itself have been a fatal flaw. that it is felt not only in the relationship between these institutions and outside Various presidents have seen the NPA and Public Protector as subordinate to forces, but within the institutions themselves and, as a result, have chosen themselves. leaders that they believe they could control to The Public Protector is currently the detriment of the institution. experiencing a crisis of public confidence. The selection of people with strong and This is because various courts, including visible political alignments made the danger of the Constitutional Court have found that politically inspired action almost inevitable. -

Assessing the Performance of South Africa's Constitution

Assessing the Performance of South Africa’s Constitution Chapter 6. The Performance of Chapter 9 Institutions Andrew Konstant © 2016 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance This is an unedited extract from a report for International IDEA by the South African Institute for Advanced Constitutional, Public, Human Rights and International Law, a Centre of the University of Johannesburg. An abridged version of the report is available for download as an International IDEA Discussion Paper: <http://www.idea.int/resources/analysis/assessing-the-performance-of-the-south-african-constitution.cfm>. Chapter 6. The Performance of Chapter 9 Institutions Andrew Konstant 6.1. Introduction The purpose of this Chapter is to consider the performance of a unique set of institutions that were set up in terms of Chapter 9 of the South African Constitution in order to support and enhance democracy and fundamental rights. The place of these institutions within the structure of government is discussed as well as their role and key goals. The focus of the chapter will be on the Public Protector, an institution set up to engage with improper conduct of organs of state; the South African Human Rights Commission, whose task is to advance the protection of fundamental rights in South African society and the Independent Electoral Commission whose task is to manage elections and ensure they are free and fair. The design and functioning of these institutions will be evaluated against a set of overarching goals they are meant to realise as well as their own specific functions. Our analysis shows that these institutions have played a vital role in advancing the goals of the South African constitution though features of their design and performance could be enhanced in ways that are detailed in the chapter. -

Powers of the Public Protector: Are Its Findings and Recommendations Legally Binding?

POWERS OF THE PUBLIC PROTECTOR: ARE ITS FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS LEGALLY BINDING? by MOLEFHI SOLOMON PHOREGO 27312837 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree: Master of Laws (LLM Research): Public Law Study Leader: Professor Danie Brand Department of Public Law, University of Pretoria November 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………………….........................vii CHAPTER 1 Introduction…..…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..1 The Public Protector as a Chapter Nine Institution………………………………………………………1 Research problem………………………………………………………………………………………………………..2 Aims and objectives of study……………………………………………………………………………………….3 Research Methodology………………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Research Questions………………………………………………………………………………………………………4 Limitations…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 Chapter Outline……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 CHAPTER 2 CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS GOVERNING THE OPERATIONS OF THE OFFICE OF THE PUBLIC PROTECTOR Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 The Constitutional provisions……………………………………………………………………………………..7 Meaning of “Appropriate remedial action’ as contained in the Constitution….…………..11 STATUTORY PROVISIONS REGULATING THE OFFICE OF THE PUBLIC PROTECTOR……...10 Section 6 of the Public Protector Act………………………………………………………………………….12 i Section 7 of the Public Protector Act………………………………………………………………………….17 Section 8 of the Public Protector Act………………………………………………………………………….19 -

ELEVEN Financing the ANC: Chancellor House, Eskom and the Dilemmas of Party finance Reform

F INANCING THE ANC ELEVEN Financing the ANC: Chancellor House, Eskom and the dilemmas of party finance reform Zwelethu Jolobe On 8 April 2010 the World Bank approved a US$3.75 billion loan to help South Africa achieve a reliable source of electricity supply. The loan, the World Bank’s largest lending engagement with South Africa since the end of apartheid, was provided to South Africa’s state-owned power utility, Eskom, and was brought about by the circumstances surrounding South Africa’s energy crisis of 2007–8, and the global financial crisis that exposed South Africa’s vulnerability to an energy shock and accompanying severe economic consequences. Named the Eskom Investment Support Project (the Eskom Project), the World Bank loan will co-finance the completion of the 4800MW Medupi coal-fired power station (US$3.05 billion), the piloting for a utility-scale 100MW wind-power project in Sere and a 100MW concentrated solar-power project with storage in Upington (US$260 million), and low-energy efficient components, including a railway to transport coal with fewer greenhouse gas emissions.1 According to Ruth Kagia, the World Bank country director for South Africa, the Eskom project offers the World Bank an opportunity to ‘strengthen its partnership with the government of South Africa’. This, according to Vijay Iyer, the World Bank energy sector manager 201 001314 Paying for Politics.indb 201 2010/09/23 3:03 PM P AYING FOR POLITICS for Africa, is the ‘biggest grid-connected renewable energy venture in any developing country’.2 The project received strong political support from South Africa. -

Thuli Madonsela Citation

CITATION: THULI MADONSELA Advocate Thulisile Madonsela was born in Johannesburg in 1962 and grew up in Soweto. Her parents, Bafana and Nomasonto, were traders and sent her to Evelyn Baring High School in Nhlangano, Swaziland, from where her family originates. After school, she worked as an assistant teacher from 1980 to 1983. Between 1984 and 1987 she worked as a legal and education officer at the Paper Printing Wood & Allied Workers Union, whilst also studying for a BA in law at the University of Swaziland. After graduating with a BA in 1987, she went on to complete an LLB at the University of the Witwatersrand in 1990. In 1992, Madonsela joined the Centre for Applied Legal Studies at Wits University as a Ford Foundation intern and then joined its Gender Research Project from 1993 to 1995. These were exciting times to be at CALS and Madonsela was particularly involved in labour law issues and in working with women in trade unions, as well as constitutional issues. Indeed, she was to forfeit a Harvard scholarship to remain engaged in South Africa on constitutional issues. She was appointed as a Technical Advisor of the Theme Committees in the Constitutional Assembly working on different aspects of the 1996 Constitution. She was also a member of a Task Team that prepared constitutional inputs for the Gauteng Province of the African National Congress, and presented the final constitutional document at the African National Congress' Gauteng Constitutional Conference in 1995. After 1994, Madonsela set up her own company to work on issues of gender and the law. -

IN the CONSTITUTIONAL COURT of SOUTH AFRICA Case No: CCT143/15 and CCT171/15

IN THE CONSTITUTIONAL COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA Case no.: CCT 143/15 In the matter between: THE ECONOMIC FREEDOM FIGHTERS Applicant and THE SPEAKER OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY, First respondent REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA PRESIDENT JACOB GEDLEYIHLEKISA ZUMA Second respondent THE PUBLIC PROTECTOR Third respondent APPLICANT’S WRITTEN SUBMISSIONS 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................... 3 EXCLUSIVE JURISDICTION: SECTION 167(4)(E) ......................................................... 5 First level: the crucial political question test ..................................................................... 8 Second level: agent-specific test ...................................................................................... 14 Third level: Parliament and the President are inseparable ............................................... 16 THE PUBLIC PROTECTOR’S REPORT AND THE PRESIDENT’S REACTION .... 17 UNFULFILLED CONSTITUTIONAL OBLIGATIONS .................................................. 28 The President: The Supreme Upholder and Protector of The Constitution ..................... 29 Parliament: Duty to Hold the National Executive Accountable ...................................... 39 FURTHER, PROCEDURAL ARGUMENTS OF THE PRESIDENT ............................. 41 Non-joinder ...................................................................................................................... 41 Prematurity ...................................................................................................................... -

12-Politcsweb-Going-Off-The-Rails

http://www.politicsweb.co.za/documents/going-off-the-rails--irr Going off the rails - IRR John Kane-Berman - IRR | 02 November 2016 John Kane-Berman on the slide towards the lawless South African state GOING OFF THE RAILS: THE SLIDE TOWARDS THE LAWLESS SOUTH AFRICAN STATE SETTING THE SCENE South Africa is widely recognised as a lawless country. It is also a country run by a government which has itself become increasingly lawless. This is so despite all the commitments to legality set out in the Constitution. Not only is the post–apartheid South Africa founded upon the principle of legality, but courts whose independence is guaranteed are vested with the power to ensure that these principles are upheld. Prosecuting authorities are enjoined to exercise their functions “without fear, favour, or prejudice”. The same duty is laid upon other institutions established by the Constitution, among them the public protector and the auditor general. Everyone is endowed with the right to “equal protection and benefit of the law”. We are all also entitled to “administrative action that is lawful, reasonable, and procedurally fair”. Unlike the old South Africa – no doubt because of it – the new Rechtsstaat was one where the rule of law would be supreme, power would be limited, and the courts would have the final say. This edifice, and these ideals, are under threat. Lawlessness on the part of the state and those who run it is on the increase. The culprits run from the president down to clerks of the court, from directors general to immigration officials, from municipal managers to prison warders, from police generals to police constables, from cabinet ministers to petty bureaucrats. -

Strengthening Constitutional Democracy: Progress and Challenges of the South African Human Rights Commission and Public Protector

NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 60 Issue 1 Twenty Years of South African Constitutionalism: Constitutional Rights, Article 7 Judicial Independence and the Transition to Democracy January 2016 Strengthening Constitutional Democracy: Progress and Challenges of the South African Human Rights Commission and Public Protector TSELISO THIPANYANE Chief Executive Officer at the Safer South Africa Foundation Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation TSELISO THIPANYANE, Strengthening Constitutional Democracy: Progress and Challenges of the South African Human Rights Commission and Public Protector, 60 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. (2015-2016). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL LAW REVIEW VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 Tseliso Thipanyane Strengthening Constitutional Democracy: Progress and Challenges of the South African Human Rights Commission and Public Protector 60 N.Y.L. Sch. L. Rev. 125 (2015–2016) ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Tseliso Thipanyane is the Chief Executive Officer at the Safer South Africa Foundation; an independent consultant on human rights, democracy, and good governance; former adjunct Lecturer-in-Law at Columbia Law School; and former Chief Executive Officer of the South African Human Rights Commission. www.nylslawreview.com 125 STRENGTHENING CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRACY NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL LAW REVIEW VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 Human rights and fundamental freedoms are the birthright of all human beings; their protection and promotion is the first responsibility of Governments.1 I. -

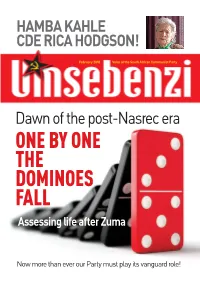

One by One the Dominoes Fall Assessing Life After Zuma

HAMBA KAHLE CDE RICA HODGSON! February 2018 Voice of the South African Communist Party Dawn of the post-Nasrec era ONE BY ONE THE DOMINOES FALL Assessing life after Zuma Now more than ever our Party must play its vanguard role! 2 Umsebenzi NEW YEAR Advancing into new, uncertain times As South Africa moves into exciting, but uncertain, times, writes Jeremy Cronin, our Party must be strategically consistent, analytically alert and tactically flexible enin is reputed to have once said on the matter (a report that somehow Mbeki… only to be re-hired and gifted “there are decades where nothing manages to leave the Guptas out of the with a fancy Dubai apartment when his happens, and weeks where decades equation). father’s fortunes turned. Lhappen.” It would be an exaggera- Yes, much of what is happening is still Over a year ago, the SACP called for tion to claim decades have been hap- half moves, reluctant shifts, or just the an independent judicial commission into pening in South Africa in the past few beginnings of long suppressed investiga- corporate capture of the state. The former weeks. We are not exactly living through tions. But we shouldn’t underestimate Public Protector, Thuli Madonsela’s State “ten days that shook the world” as John what is afoot, or fail to act vigorously in of Capture report took up this idea and Reed once described the 1917 Bolshevik support of the momentum that has now added that, since he was implicated in the Revolution. opened up. report, President Zuma could not select But we are certainly living through Everywhere, former Gupta political the judge. -

Accountability and the Role of Independent Constitutional Institutions in South Africa’S Post-Apartheid Constitutions

NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 60 Issue 1 Twenty Years of South African Constitutionalism: Constitutional Rights, Article 8 Judicial Independence and the Transition to Democracy January 2016 Accountability and the Role of Independent Constitutional Institutions in South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Constitutions HEINZ KLUG Professor of Law at the University of Wisconsin and an Honorary Senior Research Associate in the School of Law at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation HEINZ KLUG, Accountability and the Role of Independent Constitutional Institutions in South Africa’s Post- Apartheid Constitutions, 60 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. (2015-2016). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL LAW REVIEW VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 Heinz Klug Accountability and the Role of Independent Constitutional Institutions in South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Constitutions 60 N.Y.L. Sch. L. Rev. 153 (2015–2016) ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Heinz Klug is Evjue-Bascom Professor of Law at the University of Wisconsin and an Honorary Senior Research Associate in the School of Law at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. Part of this article was originally presented as a keynote address entitled “Poverty, Good Governance and Achieving the Constitution’s Promise,” at the Good Governance Conference in Pretoria, South Africa in October 2013. -

Lessons from the African Peer Review Mechanism

RESEARCH REPORT 17 Governance and APRM Programme August 2014 Getting Down to Business: Lessons from the African Peer Review Mechanism A look at the corporate governance thematic area in the Country Review Reports on Lesotho, Mauritius, Mozambique, South Africa, Tanzania and Zambia Terence Corrigan ABOUT SAIIA The South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA) has a long and proud record as South Africa’s premier research institute on international issues. It is an independent, non-government think tank whose key strategic objectives are to make effective input into public policy, and to encourage wider and more informed debate on international affairs, with particular emphasis on African issues and concerns. It is both a centre for research excellence and a home for stimulating public engagement. SAIIA’s research reports present in-depth, incisive analysis of critical issues in Africa and beyond. Core public policy research themes covered by SAIIA include good governance and democracy; economic policymaking; international security and peace; and new global challenges such as food security, global governance reform and the environment. Please consult our website www.saiia.org.za for further information about SAIIA’s work. ABOUT THE GOVERNA NCE A ND A PRM P ROGRA MME SAIIA’s Governance and African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) programme aims to place governance and African development at the centre of local and global discussions about the continent’s future. Its overall goal is to improve the ability of the APRM to contribute