Matilal's Metaethics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2016-17

Jeee|<ekeâ efjheesš& Annual Report 201201666---20120120177 केb6ीय ितबती अaययन िव िवcालय Central University of Tibetan Studies (Deemed University) Sarnath, Varanasi - 221007 www.cuts.ac.in Conference on Buddhist Pramana A Glance of Cultural Programme Contents Chapters Page Nos. 1. A Brief Profile of the University 3 2. Faculties and Academic Departments 9 3. Research Departments 45 4. Shantarakshita Library 64 5. Administration 79 6. Activities 89 Appendices 1. List of Convocations held and Honoris Causa Degrees Conferred on Eminent Persons by CUTS 103 2. List of Members of the CUTS Society 105 3. List of Members of the Board of Governors 107 4. List of Members of the Academic Council 109 5. List of Members of the Finance Committee 112 6. List of Members of the Planning and Monitoring Board 113 7. List of Members of the Publication Committee 114 Editorial Committee Chairman: Dr. Dharma Dutt Chaturvedi Associate Professor, Dean, Faculty of Shabdavidya, Department of Sanskrit, Department of Classical and Modern Languages Members: Shri R. K. Mishra Documentation Officer Shantarakshita Library Shri Tenzin Kunsel P. R. O. V.C. Office Member Secretary: Shri M.L. Singh Sr. Clerk (Admn. Section-I) [2] A BRIEF PROFILE OF THE UNIVERSITY 1. A BRIEF PROFILE OF THE UNIVERSITY The Central University of Tibetan Studies (CUTS) at Sarnath is one of its kind in the country. The University was established in 1967. The idea of the University was mooted in course of a dialogue between Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India and His Holiness the Dalai Lama with a view to educating the young Tibetan in exile and those from the Himalayan regions of India, who have religion, culture and language in common with Tibet. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay

BOOK DESCRIPTION AUTHOR " Contemporary India ". Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay. 100 Great Lives. John Cannong. 100 Most important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 100 Most Important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 1787 The Grand Convention. Clinton Rossiter. 1952 Act of Provident Fund as Amended on 16th November 1995. Government of India. 1993 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. Indian Institute of Human Rights. 19e May ebong Assame Bangaliar Ostiter Sonkot. Bijit kumar Bhattacharjee. 19-er Basha Sohidera. Dilip kanti Laskar. 20 Tales From Shakespeare. Charles & Mary Lamb. 25 ways to Motivate People. Steve Chandler and Scott Richardson. 42-er Bharat Chara Andolane Srihatta-Cacharer abodan. Debashish Roy. 71 Judhe Pakisthan, Bharat O Bangaladesh. Deb Dullal Bangopadhyay. A Book of Education for Beginners. Bhatia and Bhatia. A River Sutra. Gita Mehta. A study of the philosophy of vivekananda. Tapash Shankar Dutta. A advaita concept of falsity-a critical study. Nirod Baron Chakravarty. A B C of Human Rights. Indian Institute of Human Rights. A Basic Grammar Of Moden Hindi. ----- A Book of English Essays. W E Williams. A Book of English Prose and Poetry. Macmillan India Ltd.. A book of English prose and poetry. Dutta & Bhattacharjee. A brief introduction to psychology. Clifford T Morgan. A bureaucrat`s diary. Prakash Krishen. A century of government and politics in North East India. V V Rao and Niru Hazarika. A Companion To Ethics. Peter Singer. A Companion to Indian Fiction in E nglish. Pier Paolo Piciucco. A Comparative Approach to American History. C Vann Woodward. A comparative study of Religion : A sufi and a Sanatani ( Ramakrishana). -

Library Catalogue

Id Access No Title Author Category Publisher Year 1 9277 Jawaharlal Nehru. An autobiography J. Nehru Autobiography, Nehru Indraprastha Press 1988 historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 2 587 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 3 605 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence 4 3633 Jawaharlal Nehru. Rebel and Stateman B. R. Nanda Biography, Nehru, Historical Oxford University Press 1995 5 4420 Jawaharlal Nehru. A Communicator and Democratic Leader A. K. Damodaran Biography, Nehru, Historical Radiant Publlishers 1997 Indira Gandhi, 6 711 The Spirit of India. Vol 2 Biography, Nehru, Historical, Gandhi Asia Publishing House 1975 Abhinandan Granth Ministry of Information and 8 454 Builders of Modern India. Gopal Krishna Gokhale T.R. Deogirikar Biography 1964 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 9 455 Builders of Modern India. Rajendra Prasad Kali Kinkar Data Biography, Prasad 1970 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 10 456 Builders of Modern India. P.S.Sivaswami Aiyer K. Chandrasekharan Biography, Sivaswami, Aiyer 1969 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 11 950 Speeches of Presidente V.V. Giri. Vol 2 V.V. Giri poitical, Biography, V.V. Giri, speeches 1977 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 12 951 Speeches of President Rajendra Prasad Vol. 1 Rajendra Prasad Political, Biography, Rajendra Prasad 1973 Broadcasting Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 01 - Dr. Ram Manohar 13 2671 Biography, Manohar Lohia Lok Sabha 1990 Lohia Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 02 - Dr. Lanka 14 2672 Biography, Lanka Sunbdaram Lok Sabha 1990 Sunbdaram Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 04 - Pandit Nilakantha 15 2674 Biography, Nilakantha Lok Sabha 1990 Das Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. -

Understanding Dharma and Artha in Statecraft Through Kautilya's

UNDERSTANDING DHARMA AND ARTHA IN STATECRAFT...| 1 IDSA Monograph Series No. 53 July 2016 Understanding Dharma and Artha in Statecraft through Kautilya’s Arthashastra Pradeep Kumar Gautam 2 | P K GAUTAM Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, sorted in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA). ISBN: 978-93-82169-65-9 Disclaimer: It is certified that views expressed and suggestions made in this monograph have been made by the author in his personal capacity and do not have any official endorsement. First Published: July 2016 Price: Rs. 175 /- Published by: Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg, Delhi Cantt., New Delhi - 110 010 Tel. (91-11) 2671-7983 Fax.(91-11) 2615 4191 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.idsa.in Cover & Layout by: Geeta Kumari Printed at: M/S Manipal Technologies Ltd. UNDERSTANDING DHARMA AND ARTHA IN STATECRAFT...| 3 Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................... 5 1. Introduction ............................................................................ 7 2. The Concept of Dharma and Artha .................................... 14 3. Dharma in Dharmashastra and Arthashastra: A Comparative Analysis ...................................................... 37 4. Evaluating Dharma and Artha in the Mahabharata for Moral and Political Interpretations ........................... 72 5. Conclusion.............................................................................. 107 4 | P K GAUTAM UNDERSTANDING DHARMA AND ARTHA IN STATECRAFT...| 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank the panelists and participants in the two of my fellow seminars in 2015 for engaging with the topic with valuable insights, ideas and suggestions. -

Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts Notice Inviting Quotation for Supply of Listed Books to Ignca Rcb Reference Library

IGNCA/RCB/16.2/2017 (Vol. III) INDIRA GANDHI NATIONAL CENTRE FOR THE ARTS REGIONAL CENTRE, BENGALURU Kengunte Circle, Mallathahalli, Jnanabharati Post, BENGALURU – 560056. NOTICE INVITING QUOTATION FOR SUPPLY OF LISTED BOOKS TO IGNCA RCB REFERENCE LIBRARY 1. Annexure – (A) – General Undertaking 2. Annexure – (B) – Terms and Conditions 3. Annexure – (C) – List of Books Sealed quotations are invited from licensed book vendors/suppliers/publishers as per the details given below for “Supply of Listed books to IGNCA Regional Centre, Bengaluru”. Sl. Name of Work Cost of EMD Last date of Last date for Date of opening No. Quotation issue of submission of of quotation quotation form quotation 01. Supply of Listed Books to 200/- 15,000/- 08.11.2017 08.11.2017 09.11.2017 IGNCA RCB Reference (Rupees (Wednesday) (Wednesday) till (Thursday) at Library Fifteen till 2:00 PM 5:00 PM 3:00 PM thousand only) Page 1 of 4 IGNCA/RCB/16.2/2017 (Vol. III) INDIRA GANDHI NATIONAL CENTRE FOR THE ARTS REGIONAL CENTRE, BENGALURU – 560056. Quotation No. 02 Bengaluru, the 25th October, 2017 Name of work: Supply of Listed Books to IGNCA RCB Reference Library. 1. Sealed quotations are invited on behalf of Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, Regional Centre, Bengaluru for above named work. The quotation shall be addressed to “The Executive Director” IGNCA, Regional Centre, Kengunte Circle, Mallathahalli, Jnanabharati Post, Bengaluru – 560056 and submitted latest by 8th November, 2017 (Wednesday) till 5:00 PM and will be opened on 9th November, 2017 (Thursday) at 3:00 PM. Quotations received after the due date/time will not be accepted. -

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

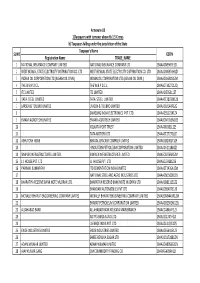

List of Books

Acession Name of Book Author LIB. No. CAB. NO. 1 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 2 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 3 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 4 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 5 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 6 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 7 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 8 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 9 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 10 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 11 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 12 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 13 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 14 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 15 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 16 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 17 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 18 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 19 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 20 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 21 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 22 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 23 The World Book Encyclopedia World Book 44/1 24 Britannica ; Book of the year EncycloBrit. 44/1 25 The World Book Atlas World Book 63/1 26 The World Book: Medical Encyclopedia World Book 9/1 27 The World Book Dictionary World Book 44/1 28 The World Book Dictionary World Book 44/1 29 The World Book Dictionary World Book 44/1 30 The World Book Dictionary World Book 44/1 31 The 1998 World Book Year Book World Book 44/1 32 The New Encyclopedia Britannica Encyclo Britan. -

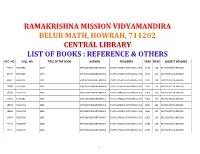

Ramakrishna Mission Vidyamandira Belur Math, Howrah, 711202 Central Library List of Books : Reference & Others Acc

RAMAKRISHNA MISSION VIDYAMANDIRA BELUR MATH, HOWRAH, 711202 CENTRAL LIBRARY LIST OF BOOKS : REFERENCE & OTHERS ACC. NO. CALL. NO. TITLE OF THE BOOK AUTHOR PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE SUBJECT HEADING 44638 R032/ENC 1978 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1978 150 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 44639 R032/ENC 1979 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1979 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 44641 R-032/BRI 1981 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1981 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 15648 R-032/BRI 1982 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1982 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 15649 R-032/ENC 1983 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1983 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 17913 R032/ENC 1984 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1984 350 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 18648 R-032/ENC 1985 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1985 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 18786 R-032/ENC 1986 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1986 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 19693 R-032/ENC 1987 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1987 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21140 R-032/ENC 1988 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1988 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21141 R-032/ENC 1989 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1989 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 1 ACC. NO. CALL. NO. TITLE OF THE BOOK AUTHOR PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE SUBJECT HEADING 21426 R-032/ENC 1990 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1990 150 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21797 R-032/ENC 1991 ENYCOLPAEDIA -

Introduction*

INTRODUCTION | 1 Introduction* Radhavallabh Tripathi IT is almost an impossible task for a single person to present a comprehensive view on the status and trends of Sanskrit studies in a vast country like India. What is being done here would just appear to be a sketchy account, containing snippets of information, that is to be further corroborated, properly analysed and explored. India is divided into 28 states, 7 union territories and 644 districts. There is hardly any district or region where Sanskrit is not studied in some form or the other. Sanskrit is mentioned in the list of 22 major languages, officially accepted in the Constitution of India, and it is also one of the three languages there, that have an all India character. Teaching, Education and Research In India there are 282 universities as per the records with the AIU, at least 112 of which have postgraduate and research departments of Sanskrit. The number of colleges teaching Sanskrit is around 10,000. “Modern methods” are adopted in these institutions for teaching programmes in Sanskrit. Apart from these universities and colleges, there are 16 Sanskrit universities and a number of Sanskrit pÀÇhaœÀlÀs or Sanskrit * This is an enlarged and revised version of my paper “Sanskrit Studies in India” published in the Bulletin of IASS, 2012. 2 | SIXTY YEARS OF SANSKRIT STUDIES: VOL. 1 colleges where traditional method also known as pÀÇhaœÀlÀ paddhati is practised. As per a recent state-wise survey conducted by the Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan (RSkS) the number of Sanskrit pÀÇhaœÀlÀs in Madhya Pradesh is 644, in Chhattisgarh 32, in Uttar Pradesh 1347, Uttarakhand 115, in Karnataka it is 290, in Orissa 433, Punjab 8, Rajasthan 1698, Sikkim 36, Tamil Nadu 55, and in Himachal Pradesh 129, Andhra Pradesh 509, Assam 83, Bihar 717, Goa 4, Gujarat 63, Haryana 74, Jammu & Kashmir 43, Jharkhand 3, Kerala 31, Maharashtra 63, Manipur 8. -

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1B 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores b) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the State Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LTD 19AAACN9967E1Z0 2 WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD 19AAACW6953H1ZX 3 INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) 19AAACI1681G1ZM 4 THE W.B.P.D.C.L. THE W.B.P.D.C.L. 19AABCT3027C1ZQ 5 ITC LIMITED ITC LIMITED 19AAACI5950L1Z7 6 TATA STEEL LIMITED TATA STEEL LIMITED 19AAACT2803M1Z8 7 LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED 19AAACL0140P1ZG 8 SAMSUNG INDIA ELECTRONICS PVT. LTD. 19AAACS5123K1ZA 9 EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED 19AABCN7953M1ZS 10 KOLKATA PORT TRUST 19AAAJK0361L1Z3 11 TATA MOTORS LTD 19AAACT2727Q1ZT 12 ASHUTOSH BOSE BENGAL CRACKER COMPLEX LIMITED 19AAGCB2001F1Z9 13 HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED. 19AAACH1118B1Z9 14 SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. 19AAECS0765R1ZM 15 J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD 19AABCJ5928J2Z6 16 PARIMAL KUMAR RAY ITD CEMENTATION INDIA LIMITED 19AAACT1426A1ZW 17 NATIONAL STEEL AND AGRO INDUSTRIES LTD 19AAACN1500B1Z9 18 BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. 19AAACB8111E1Z2 19 BHANDARI AUTOMOBILES PVT LTD 19AABCB5407E1Z0 20 MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED 19AABCM9443R1ZM 21 BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED 19AAACB2902M1ZQ 22 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLAHABAD BANK KOLKATA MAIN BRANCH 19AACCA8464F1ZJ 23 ADITYA BIRLA NUVO LTD. 19AAACI1747H1ZL 24 LAFARGE INDIA PVT. LTD. 19AAACL4159L1Z5 25 EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACE6641E1ZS 26 SHREE RENUKA SUGAR LTD. 19AADCS1728B1ZN 27 ADANI WILMAR LIMITED ADANI WILMAR LIMITED 19AABCA8056G1ZM 28 AJAY KUMAR GARG OM COMMODITY TRADING CO. -

Catalogue of the Journal of Ganganatha Jha Campus Volume XXII-XXX

The Journal Of The Ganganatha Jha Research Institute Volume XXII, Part – 1-2, November-February 1965-66 Sl. Subject Author Page Nu. 1 Karma and Rebirth Prof. K. C. Varadachari 1–12 2 What anandavardhan Meant by Dhvani? Dr. Chandikaprasada Shukla 13-22 Reviews on some Alleged causes of the 3 Lal Mani Joshi 23-38 Decline of Buddhism in India Kali as a Metaphysical concept in the 4 Navjivan Rastogi 39-54 Krama system of Kashmir Shaivism 5 Appreciation of yaska as an Etymologist Dr. S. K. Gupta 55–96 6 Source of Kalidasa’s Rtu-Samhara R. B. Kulshrestha 97-102 Three Jain Inscriptyions from Jabalipur 7 Sadhu Ram 103-110 (Jalor) Interpretation of a passage in Rock Edict 8 Sadhu Ram 111-114 IV of Ashoka 9 Rebellion of Khan Sahib of Madurai Dr. K. Rajayyan 115-128 “Glories of the later Veershaiva Rulers of 10 the Sangama Dynasty of Vijayanagar B. V. Sreenivasan 129-150 Empire” on chronological Basis 11 A note on the nativity of the Kriyayogasara Om Prakash 151-154 12 The Series of “Know Thyself” books Antony Philip Halas 155-157 Volume XXII, Part – 3-4, May-August 1966 Sl. Subject Author Page Nu. Jayantabhatta and Vacaspatimishra : Their 13 Date and Their Significance for the Dr. B. H. Kapadia 159-176 chronology of Vedanta 14 God as the Author of vedas Hem Chandra Joshi 177-192 Revisions of the Manusmriti and the 15 Dr. R. S. Betai 193-202 Background of there : A fresh study Rhetorical Embellishments in the 16 Dr. Santosh Kumari Sharma 203-236 Haravijaya Glories of the Later Veerashaiva Rulers of 17 the Sangam Dynasty of Vijayanagar Empire B.