Tourism and Development in Nepal Stan Stevens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

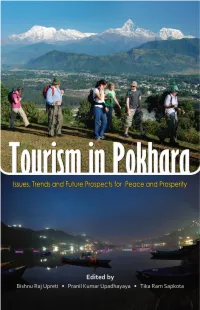

Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity

Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity 1 Tourism in Pokhara Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity Edited by Bishnu Raj Upreti Pranil Kumar Upadhayaya Tikaram Sapkota Published by Pokhara Tourism Council, Pokhara South Asia Regional Coordination Office of NCCR North-South and Nepal Centre for Contemporary Research, Kathmandu Kathmandu 2013 Citation: Upreti BR, Upadhayaya PK, Sapkota T, editors. 2013. Tourism in Pokhara Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity. Kathmandu: Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC), South Asia Regional Coordination Office of the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR North- South) and Nepal Center for Contemporary Research (NCCR), Kathmandu. Copyright © 2013 PTC, NCCR North-South and NCCR, Kathmandu, Nepal All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-9937-2-6169-2 Subsidised price: NPR 390/- Cover concept: Pranil Upadhayaya Layout design: Jyoti Khatiwada Printed at: Heidel Press Pvt. Ltd., Dillibazar, Kathmandu Cover photo design: Tourists at the outskirts of Pokhara with Mt. Annapurna and Machhapuchhre on back (top) and Fewa Lake (down) by Ashess Shakya Disclaimer: The content and materials presented in this book are of the respective authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC), the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR North-South) and Nepal Centre for Contemporary Research (NCCR). Dedication To the people who contributed to developing Pokhara as a tourism city and paradise The editors of the book Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity acknowledge supports of Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC) and the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) North-South, co-funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), and the participating institutions. -

Three Passes Nepal Trek Trip Notes 2022

THREE PASSES TREK 2022 TRIP NOTES THREE PASSES TREK TRIP NOTES 2022 TREK DETAILS Dates: Trip 1: April 30 to May 25 Trip 2: September 13 to October 8 Trip 3: November 2–27 Duration: 26 days Departure: ex Kathmandu, Nepal Price: US$4,700 per person Taking in the spectacular views on the Kongma La. Photo: Suze Kelly The trek through Nepal’s ‘Three Passes’ takes in some of the most exciting and picturesque scenery in the Himalaya. The landscape is varied and spectacular; the lodgings and tracks range from the time-worn paths of the Khumbu to the isolated and less frequented Renjo Pass region. Sometimes strenuous trekking is continuously airport by our Kathmandu staff, who whisk us rewarded with dramatic Himalayan scenes, through the thriving city to your hotel. including four of the world’s eight highest peaks—Cho Oyu (8,201m/26,900ft), Makalu Once everybody has arrived we have a team (8,463m/27,765ft), Lhotse (8,516m/27,940ft) and meeting where introductions and the trip outline Everest (8,850m/29,035ft). are completed. You will be briefed on the trip preparations and we can sort out any queries you have. Time spent admiring breathtaking mountain vistas are complemented by visits to Sherpa villages, Your guide will advise you on good shopping and homes and monasteries offering you an insight the better restaurants to visit while you are in the into the quiet but, culturally vibrant Sherpa way city. There are plenty of shops and entertainment of life. This trek visits Everest Base Camp and to suit all tastes. -

GLACIERS of NEPAL—Glacier Distribution in the Nepal Himalaya with Comparisons to the Karakoram Range

Glaciers of Asia— GLACIERS OF NEPAL—Glacier Distribution in the Nepal Himalaya with Comparisons to the Karakoram Range By Keiji Higuchi, Okitsugu Watanabe, Hiroji Fushimi, Shuhei Takenaka, and Akio Nagoshi SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD Edited by RICHARD S. WILLIAMS, JR., and JANE G. FERRIGNO U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1386–F–6 CONTENTS Glaciers of Nepal — Glacier Distribution in the Nepal Himalaya with Comparisons to the Karakoram Range, by Keiji Higuchi, Okitsugu Watanabe, Hiroji Fushimi, Shuhei Takenaka, and Akio Nagoshi ----------------------------------------------------------293 Introduction -------------------------------------------------------------------------------293 Use of Landsat Images in Glacier Studies ----------------------------------293 Figure 1. Map showing location of the Nepal Himalaya and Karokoram Range in Southern Asia--------------------------------------------------------- 294 Figure 2. Map showing glacier distribution of the Nepal Himalaya and its surrounding regions --------------------------------------------------------- 295 Figure 3. Map showing glacier distribution of the Karakoram Range ------------- 296 A Brief History of Glacier Investigations -----------------------------------297 Procedures for Mapping Glacier Distribution from Landsat Images ---------298 Figure 4. Index map of the glaciers of Nepal showing coverage by Landsat 1, 2, and 3 MSS images ---------------------------------------------- 299 Figure 5. Index map of the glaciers of the Karakoram Range showing coverage -

A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya

The Himalaya by the Numbers A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya Richard Salisbury Elizabeth Hawley September 2007 Cover Photo: Annapurna South Face at sunrise (Richard Salisbury) © Copyright 2007 by Richard Salisbury and Elizabeth Hawley No portion of this book may be reproduced and/or redistributed without the written permission of the authors. 2 Contents Introduction . .5 Analysis of Climbing Activity . 9 Yearly Activity . 9 Regional Activity . .18 Seasonal Activity . .25 Activity by Age and Gender . 33 Activity by Citizenship . 33 Team Composition . 34 Expedition Results . 36 Ascent Analysis . 41 Ascents by Altitude Range . .41 Popular Peaks by Altitude Range . .43 Ascents by Climbing Season . .46 Ascents by Expedition Years . .50 Ascents by Age Groups . 55 Ascents by Citizenship . 60 Ascents by Gender . 62 Ascents by Team Composition . 66 Average Expedition Duration and Days to Summit . .70 Oxygen and the 8000ers . .76 Death Analysis . 81 Deaths by Peak Altitude Ranges . 81 Deaths on Popular Peaks . 84 Deadliest Peaks for Members . 86 Deadliest Peaks for Hired Personnel . 89 Deaths by Geographical Regions . .92 Deaths by Climbing Season . 93 Altitudes of Death . 96 Causes of Death . 97 Avalanche Deaths . 102 Deaths by Falling . 110 Deaths by Physiological Causes . .116 Deaths by Age Groups . 118 Deaths by Expedition Years . .120 Deaths by Citizenship . 121 Deaths by Gender . 123 Deaths by Team Composition . .125 Major Accidents . .129 Appendix A: Peak Summary . .135 Appendix B: Supplemental Charts and Tables . .147 3 4 Introduction The Himalayan Database, published by the American Alpine Club in 2004, is a compilation of records for all expeditions that have climbed in the Nepal Himalaya. -

Journal of Tourism & Adventure

ISSN 2645-8683 Journal of Tourism & Adventure Vol. 1 No. 1 Year 2018 Editor-in-Chief Prof. Ramesh Raj Kunwar Janapriya Multiple Campus (JMC) (Affi liated to Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal) Aims and scope Journal of Tourism & Adventure (JTA) is an annual double blind peer-reviewed journal launched by the Tribhuvan University, Janapriya Multiple Campus, Pokhara, Nepal. Th is journal welcomes original academic and applied research including multi- and interdisciplinary approaches focusing on various fi elds of tourism and adventure. Th e purpose of this journal is to disseminate the knowledge and ideas of tourism and hospitality in general and adventure in particular to the students, researchers, journalists, policy makers, planners, entrepreneurs and other general readers. It is high time to make this eff ort for tourism innovation and development. It is believed that this knowledge based platform will make the industry and the institutions stronger. Call for papers Th e journal welcomes the following topics: tourism, mountain tourism and mountaineering tourism, risk management, safety and security, tourism and natural disaster, accident, injuries, medicine and rescue, cultural heritage tourism, festival tourism, pilgrimage tourism, rural tourism, village tourism, urban tourism, geo-tourism, paper on extreme adventure tourism activities, ecotourism, environmental tourism, hospitality, event tourism, voluntourism, sustainable tourism, wildlife tourism, dark tourism, nostalgia tourism, tourism planning, destination development, tourism marketing, human resource management, adventure tourism education, tourism and research methodology, guiding profession, tourism, confl ict and peace and remaining other areas of sea, air and land based adventure tourism research. We welcome submissions of research paper on annual bases by the end of June for 2nd issue of this journal onward. -

The Gaze Journal of Tourism and Hospitality (2021) 12:1, 88-111 the GAZE JOURNAL of TOURISM and HOSPITALITY

The Gaze Journal of Tourism and Hospitality (2021) 12:1, 88-111 THE GAZE JOURNAL OF TOURISM AND HOSPITALITY Conveying Impetus for Fostering Tourism and Hospitality Entrepreneurship in Touristic Destination: Lessons Learnt from Pokhara, Nepal Niranjan Devkota Quest International College, Pokhara University, Nepal [email protected] Udaya Raj Paudel Quest International College, Pokhara University, Nepal [email protected] Udbodh Bhandari Quest International College, Pokhara University, Nepal [email protected] Article History Abstract Received 24 August 2020 Accepted 10 October 2020 Th is research explores the inter connectedness in entrepreneurs’ and tourists’ perception about western infl uence in business culture of touristic city – Pokhara, Nepal and provides suggestions for fostering sustainable tourism development Keywords of the destination. Primary data results are drawn in which Sustainable researchers have collected 249 data from tourists’ viewpoint, tourism, tourism 395 from determining provincial government roles and 395 entrepreneurship, from hospitality entrepreneurship along with key informants socio-cultural interview with experts’ viewpoints for generating practical identities, role solutions of the existing problems in order to enhance hospitality of government, and tourism business for progress and sustainability. Based on Pokhara, Nepal this triangular data results and secondary resources’ analysis, this research concludes that, for the sustainable tourism business in Pokhara, the entrepreneurs in the area should recognize, preserve, promote and sustain local socio-cultural Corresponding Editor practices; tourists’ viewpoints should be addressed and Ramesh Raj Kunwar [email protected] Gandaki provincial government roles must be constructive. Copyright © 2021 Authors Published by: International School of Tourism and Hotel Management, Kathmandu, Nepal ISSN 2467-933X Devkota/Paudel/ Bhandari: Conveying Impetus for Fostering Tourism and Hospitality.. -

Nepal Side, We Must Mention Prof

The Journal of Newar Studies Swayambhv, Ifliihichaitya Number - 2 NS 1119 (TheJournal Of Newar Studies) NUmkL2 U19fi99&99 It has ken a great pleasure bringing out the second issue of EdltLlo the journal d Newar Studies lijiiiina'. We would like to thank Daya R Sha a Gauriehankar Marw&~r Ph.D all the members an bers for their encouraging comments and financial support. ivc csp~iilly:-l*-. urank Prof. Uma Shrestha, Western Prof.- Todd ttwria Oregon Univers~ty,who gave life to this journd while it was still in its embryonic stage. From the Nepal side, we must mention Prof. Tej Shta Sudip Sbakya Ratna Kanskar, Mr. Ram Shakya and Mr. Labha Ram Tuladhar who helped us in so many ways. Due to our wish to publish the first issue of the journal on the Sd Fl~ternatioaalNepal Rh&a levi occasion of New Nepal Samht Year day {Mhapujii), we mhed at the (INBSS) Pdand. Orcgon USA last minute and spent less time in careful editing. Our computer Nepfh %P Puch3h Amaica Orcgon Branch software caused us muble in converting the files fm various subrmttd formats into a unified format. We learn while we work. Constructive are welcome we try Daya R Shakya comments and will to incorporate - suggestions as much as we can. Atedew We have received an enormous st mount of comments, Uma Shrcdha P$.D.Gaurisbankar Manandhar PIID .-m -C-.. Lhwakar Mabajan, Jagadish B Mathema suggestions, appreciations and so forth, (pia IcleI to page 94) Puma Babndur Ranjht including some ~riousconcern abut whether or not this journal Rt&ld Rqmmtatieca should include languages other than English. -

Nepal 1982 Letter from Kathmandu

199 Nepal 1982 Letter from Kathmandu Mike Cheney Post-Monsoon, 1981 Of the 42 expeditions which arrived in Nepal for the post-monsoon season, 17 were successful and 25 unsuccessful. The weather right across the Nepal Himal was exceptionally fine during the whole ofOctober and November with the exception of the first week in November, when a cyclone in western India brought rain and snow for 2 or 3 days. As traditionally happens, the Monsoon finished right on time with a major downpour of rain on 28 September. The worst of the storm was centred over a fairly small part of Central Nepal, the area immediately south of the Annapurna range. The heavy snowfalls caused 6 deaths (2 Sherpas, 2 Japanese and 2 French) on Annapurna Himal expeditions, over 200 other Nepalis also died, and many more lost their homes and all their possessions-the losses on expeditions were small indeed compared with those of the Hill and Terai peoples. Four other expedition members died as a result of accidents-2 Japanese and 2 Swiss. Winter season, 1981/82 There were four foreign expeditions during the winter climbing season, which is December and January in Nepal. Two expeditions were on Makalu-one British expedition of 6 members, led by Ron Rutland, and one French. In addition there was an American expedition to Pumori and a Canadian expedition to Annapurna IV. The American expedition to Pumori was successful. Pre-Monsoon, 1982 This was one of the most successful seasons for many years. Of the 28 expeditions attempting 26 peaks-there were 2 expeditions on Kanchenjunga and 2 on Lamjung-21 were successful. -

Download the Annual Review 2020

SIR EDMUND HILLARY’S HIMALAYAN TRUST A FOREWORD FROM OUR PatrON Letter FROM THE ChairpersON This is an especially challenging year for the communities in Nepal where the Himalayan 2020 is the Year of Covid – or more correctly, the First Year of Covid as its Trust works. The COVID-19 pandemic put a stop to tourism in the Solukhumbu which consequences will be as profound in 2021 as they are this year. The population of has been such a vital source of income for communities. Yet, keeping the communities 100,000 in the District of Solukhumbu is dependent at a base level on agriculture, but safe from COVID-19 must be a top priority, knowing that it can strike down people of the tourism/trekking, and remittances, which have lifted households above subsistence all ages and is particularly dangerous for older people and those of all ages with health have collapsed because of Covid. Prior to the revolution of 1950, the Sherpas and vulnerabilities. The Nepalese Government announced that the autumn mountaineering other hill peoples of Solukhumbu had no schools or healthcare. Their migrant workers season could operate. While that brings income, it obviously also comes with risks. went no further than Darjeeling for road-building or carrying loads for Everest The Himalayan Trust launched an appeal for emergency medical supplies and personal expeditions via Tibet. Infectious diseases kept average life expectancy under the protective equipment for the Solukhumbu which has been well supported, and will age of 50. need to continue to be as more people from outside the region make their way there. -

HTN-Newsletter-Number-4

3 NUMBER 04 Himalayan Trust Nepal JAN- MAR QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER 2 0 19 It is not the mountain we conquer but ourselves. FOUNDER Sir Edmund Hillary - Sir Edmund Hillary ______________________________ Mrs. Ingrid Versen, chairwoman of Sir Edmund Hillary Stiftung, Germany with Sir Edmund Hillary HONORARY MEMBERS 11th Anniversary of Sir Ed marked Norbu Tenzing Norgay Phurba Sona Sherpa The executive board, honorary member, general member, mayor of Khumbu Reinhold Messner Pasanglhamu Rural Municipality, ward representatives and staff met at Prof. Wolfgang Nairz Himalayan Trust Nepal (HTN) office, lit butter lamp and offered khada to Sir Ed's Fabienne Clauss portrait to commemorate the 11th Anniversary of Sir Ed's demise on the 11th Ingrid Versen Manfred Haupl January 2019. On that very day, an interaction programme was organized between the local government representatives, HTN board members and staff at BOARD MEMBERS HTN office for expanding the collaboration. Pasang Dawa Sherpa Chairman Tashi Jangbu Sherpa Vice-chairman Thukten Sherpa Treasurer Dr. Mingma Norbu Sherpa Secretary Pasang Sherpa Lama Chairman of HTN, Mr. Pasang Dawa Sherpa and Chairman of Khumbu Pasanglhamu Rural Joint Secretary Honorary member of HTN, Mrs. Phurba Sona Municipality, Mr. Nima Dorjee Sherpa offering Ang Temba Sherpa Sherpa offered Khada to Sir Ed’s photo. khada to Sir Ed's portrait Member Lhakpa Tenji Lama Member Dawa Phuti Sherpa Interaction held among the local government representtives, Member headmaster of Khumjung school and Yangji Doma Sherpa HTN board members and staff at HTN Member office Team building workshop conducted HTN board members and staff during the team building workshop at Nagarkot. -

The Journey of Nepal Bhasa from Decline to Revitalization — Resha Maharjan Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies May 2018

Center for Sami Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Science and Education The Journey of Nepal Bhasa From Decline to Revitalization — Resha Maharjan Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies May 2018 The Journey of Nepal Bhasa From Decline to Revitalization A thesis submitted by Resha Maharjan Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies The Centre of Sami Studies (SESAM) Faculty of Humanities, Social Science and Education UIT The Arctic University of Norway May 2018 Dedicated to My grandma, Nani Maya Dangol & My children, Prathamesh and Pranavi मा車भाय् झीगु म्हसिका ख: (Ma Bhay Jhigu Mhasika Kha) ‘MOTHER TONGUE IS OUR IDENTITY’ Cover Photo: A boy trying to spin the prayer wheels behind the Harati temple, Swoyambhu. The mantra Om Mane Padme Hum in these prayer wheels are written in Ranjana lipi. The boy in the photo is wearing the traditional Newari dress. Model: Master Prathamesh Prakash Shrestha Photo courtesy: Er. Rashil Maharjan I ABSTRACT Nepal Bhasa is a rich and highly developed language with a vast literature in both ancient and modern times. It is the language of Newar, mostly local inhabitant of Kathmandu. The once administrative language, Nepal Bhasa has been replaced by Nepali (Khas) language and has a limited area where it can be used. The language has faced almost 100 years of suppression and now is listed in the definitely endangered language list of UNESCO. Various revitalization programs have been brought up, but with limited success. This main goal of this thesis on Nepal Bhasa is to find the actual reason behind the fall of this language and hesitation of the people who know Nepal Bhasa to use it. -

Landscape Change in Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) National Park, Khumbu, Nepal

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 17 Number 2 Himalayan Research Bulletin: Article 16 Solukhumbu and the Sherpa 1997 Landscape Change in Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) National Park, Khumbu, Nepal Alton C. Byers Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Byers, Alton C.. 1997. Landscape Change in Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) National Park, Khumbu, Nepal. HIMALAYA 17(2). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol17/iss2/16 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Landscape Change in Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) National Park, Khumbu, Nepal Alton C. Byers The Mountain Institute This study uses repeat photography as the primary Introduction research tool to analyze processes of physical and Repeat photography, or precise replication and cultural landscape change in the Khumbu (M!. Everest) interpretation of historic landscape scenes, is an region over a 40-year period (1955-1995). The study is analytical tool capable of broadly clarifying the patterns a continuation of an on-going project begun by Byers in and possible causes of contemporary landscapellanduse 1984 that involves replication of photographs originally changes within a given region (see: Byers 1987a1996; taken between 1955-62 from the same five photo 1997). As a research tool, it has enjoyed some utility points. The 1995 investigation reported here provided in the United States during the past thirty years (see: the opportunity to expand the photographic data base Byers 1987b; Walker 1968; Heady and Zinke 1978; from five to 26 photo points between Lukla (2,743 m) Gruell 1980; Vale, 1982; Rogers et al.