Yitzhak Rabin and the Price of Peace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ihe White House Iashington

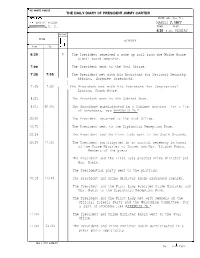

HE WHITE HOUSE THE DAILY DIARY OF PRESIDE N T JIMMY CARTER LOCATION DATE (MO., Day, Yr.) IHE WHITE HOUSE MARCH 7, 1977 IASHINGTON, D. C. TIME DAY 6:30 a.m. MONDAY PHONE TIME = 0 E -u ACTIVITY 7 K 2II From To L p! 6:30 R The President received a wake up call from the White House signal board operator. 7:oo The President went to the Oval Office. 7:30 7:35 The President met with his Assistant for National Security Affairs,Zbigniew Brzezinski. 7:45 7:50 I I, The President met with his Assistant for Congressional Liaison, Frank Moore. 8:Ol The President went to the Cabinet Room. 8:Ol 10:05 The President participated in a Cabinet meeting For a list of attendees,see APPENDIX "A." 1O:05 The President returned to the Oval Office. 1O:25 The President went to the Diplomatic Reception Room. 1O:26 The President and the First Lady went to the South Grounds. 1O:26 1l:OO The President participated in an arrival ceremony in honor of the Prime Minister of Israel and Mrs. Yitzhak Rabin. Members of the press The President and the First Lady greeted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin. The Presidential party went to the platform. 10:35 10:45 The President and Prime Minister Rabin exchanged remarks. The President and the First Lady escorted Prime Minister and Mrs. Rabin to the Diplomatic Reception Room. The President and the First Lady met with members of the Official Israeli Party and the Welcoming Committee. For a list of attendees ,see APPENDIX& "B." 11:oo The President and Prime Minister Rabin went to the Oval Office. -

The Nobel Peace Prize

TITLE: Learning From Peace Makers OVERVIEW: Students examine The Dalai Lama as a Nobel Laureate and compare / contrast his contributions to the world with the contributions of other Nobel Laureates. SUBJECT AREA / GRADE LEVEL: Civics and Government 7 / 12 STATE CONTENT STANDARDS / BENCHMARKS: -Identify, research, and clarify an event, issue, problem or phenomenon of significance to society. -Gather, use, and evaluate researched information to support analysis and conclusions. OBJECTIVES: The student will demonstrate the ability to... -know and understand The Dalai Lama as an advocate for peace. -research and report the contributions of others who are recognized as advocates for peace, such as those attending the Peace Conference in Portland: Aldolfo Perez Esquivel, Robert Musil, William Schulz, Betty Williams, and Helen Caldicott. -compare and contrast the contributions of several Nobel Laureates with The Dalai Lama. MATERIALS: -Copies of biographical statements of The Dalai Lama. -List of Nobel Peace Prize winners. -Copy of The Dalai Lama's acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize. -Bulletin board for display. PRESENTATION STEPS: 1) Students read one of the brief biographies of The Dalai Lama, including his Five Point Plan for Peace in Tibet, and his acceptance speech for receiving the Nobel Prize for Peace. 2) Follow with a class discussion regarding the biography and / or the text of the acceptance speech. 3) Distribute and examine the list of Nobel Peace Prize winners. 4) Individually, or in cooperative groups, select one of the Nobel Laureates (give special consideration to those coming to the Portland Peace Conference). Research and prepare to report to the class who the person was and why he / she / they won the Nobel Prize. -

Industry, State, and Electrical Technology in the Ruhr Circa 1900 Edmund Todd University of New Haven, [email protected]

University of New Haven Digital Commons @ New Haven History Faculty Publications History 1989 Industry, State, and Electrical Technology in the Ruhr Circa 1900 Edmund Todd University of New Haven, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.newhaven.edu/history-facpubs Part of the History Commons Publisher Citation Todd, Edmund N.. “Industry, State, and Electrical Technology in the Ruhr Circa 1900”. Osiris 5 (1989): 242–259. Comments Osiris is Published by The nivU ersity of Chicago Press on behalf of The iH story of Science Society. See journal homepage here. - KAkhomw dfts MellSO4 Wratr itnja is~wjt', tyvW4* , A a .. Sl~r& -- 'ia Zb4v-d,#IpwA# b*s*W? Atw &whasI..i Skhml We~ '. odl4e I~e, X- &OWL, eda Wowtd f ~fttrv wA t AA *rsw D A .h_ tQA, ' 0omwv *~~~~~~ _e __a t - ie6o a ge iEwDz. c/a~tsw ............................ AV AN40ff v IIA~jr~W~jP~O419Z.Deg#|edA6< Hap,-~,n,/O' z n ____ /t/w.~~~~~ee mfifffivo s s/okYo8 6W. 44 , - =*0 0 a(~~~~~~~~~~ 4~~~~~~~%-Jvo 0 We W~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~0 ts t? jf o + otw ..~ ~~~~ R~ilinghousan <t O*s'-\ . e~ ~pgeeo Hi, - v, - Raj;cI Ai"if d. \ Lfres i D~t 2 . o pf j ,R s O a r ~~~A/dd ~~~~~ ~~ e40,01O O~~~~~~~ 0tett Reki4hua 0 WI& %7a.? O .7rmf; V.os : ; \; *e ?~~~~~~~~~~14" O~empro Wr~ PP ARM ftmm> r , ~f.k (IrdingOin,? , i h#= hen 0 444SI.,~~~~~~~~~~a. NW.-I's~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~t 40- 'tQ y O - 5p oKrh OW-1dA*i0v&"OitV DU,, Id erf~o? 0 rM _ m' C nEbrfd5mI N~ h Rocr -ie/,,aEno# ~ v "'~~~~~~ o < ~~~~~~~~i.N: afd EOid.,. -

7. Politics and Diplomacy

Hoover Press : Zelnick/Israel hzeliu ch7 Mp_119 rev1 page 119 7. Politics and Diplomacy as israeli forces were clearing recalcitrant settlers from their Gaza homes on August 16, 2005, Khalil Shikaki, director of the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research (PSR) in Ra- mallah, published a column in the Jerusalem Post headlined, “How Sharon and Abbas Can Both Win.”1 Shikaki, a pollster and political analyst respected in Israel and the west, questioned the wisdom of Israeli unilateralism in Gaza and on the West Bank as opposed to Lebanon, where no one on the other side wanted to talk. Here, he argued, Hamas may be as close-minded as Hez- bollah, preferring to paint Israel’s withdrawal as a victory for Pal- estinian resistance, but Abu Mazen, supported by Palestinian pub- lic opinion, wanted to reduce tensions and negotiate. Make him look good by easing restrictions on Palestinian trade and move- ment, and he will help Sharon and Israel by defeating Hamas and talking about the terms for settling the conflict. In other words, let the PA rather than Hamas control the Palestinian narrative of withdrawal. Shakaki updated his survey data two months later for a con- ference at Brandeis University hosted by Shai Feldman, director of the Crown Center for Middle East Studies and former director of the Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies in Tel Aviv. By that October conference, 84 percent of Palestinians were convinced that violence had played a role in the Israeli withdrawal. Irre- 1. Khalil Shikaki, “How Sharon and Abbas Can Both Win,” Jerusalem Post, August 16, 2005. -

The Labor Party and the Peace Camp

The Labor Party and the Peace Camp By Uzi Baram In contemporary Israeli public discourse, the preoccupation with ideology has died down markedly, to the point that even releasing a political platform as part of elections campaigns has become superfluous. Politicians from across the political spectrum are focused on distinguishing themselves from other contenders by labeling themselves and their rivals as right, left and center, while floating around in the air are slogans such as “political left,” social left,” “soft right,” “new right,” and “mainstream right.” Yet what do “left” and “right” mean in Israel, and to what extent do these slogans as well as the political division in today’s Israel correlate with the political traditions of the various parties? Is the Labor Party the obvious and natural heir of The Workers Party of the Land of Israel (Mapai)? Did the historical Mapai under the stewardship of Ben Gurion view itself as a left-wing party? Did Menachem Begin’s Herut Party see itself as a right-wing party? The Zionist Left and the Soviet Union As far-fetched as it may seem in the eyes of today’s onlooker, during the first years after the establishment of the state, the position vis-à-vis the Soviet Union was the litmus test of the left camp, which was then called “the workers’ camp.” This camp viewed the centrist liberal “General Zionists” party, which was identified with European liberal and middle-class beliefs in private property and capitalism, as its chief ideological rival (and with which the heads of major cities such as Tel Aviv and Ramat Gan were affiliated). -

Yitzhak Rabin

YITZHAK RABIN: CHRONICLE OF AN ASSASSINATION FORETOLD Last year, architect-turned-filmmaker Amos Gitaï directed Rabin, the Last EN Day, an investigation into the assassination, on November 4, 1995, of the / Israeli Prime Minister, after a demonstration for peace and against violence in Tel-Aviv. The assassination cast a cold and brutal light on a dark and terrifying world—a world that made murder possible, as it suddenly became apparent to a traumatised public. For the Cour d’honneur of the Palais des papes, using the memories of Leah Rabin, the Prime Minister’s widow, as a springboard, Amos GitaI has created a “fable” devoid of formality and carried by an exceptional cast. Seven voices brought together to create a recitative, “halfway between lament and lullaby,” to travel back through History and explore the incredible violence with which the nationalist forces fought the peace project, tearing Israel apart. Seven voices caught “like in an echo chamber,” between image-documents and excerpts from classic and contemporary literature— that bank of memory that has always informed the filmmaker’s understanding of the world. For us, who let the events of this historic story travel through our minds, reality appears as a juxtaposition of fragments carved into our collective memory. AMOS GITAI In 1973, when the Yom Kippur War breaks out, Amos Gitai is an architecture student. The helicopter that carries him and his unit of emergency medics is shot down by a missile, an episode he will allude to years later in Kippur (2000). After the war, he starts directing short films for the Israeli public television, which has now gone out of business. -

The Limits of the Artistic Imagination, and the Secular Intellectual Edward W

Macalester International Volume 3 Literature, the Creative Imagination, and Article 7 Globalization Spring 5-31-1996 The Limits of the Artistic Imagination, and the Secular Intellectual Edward W. Said Columbia University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl Recommended Citation Said, Edward W. (1996) "The Limits of the Artistic Imagination, and the Secular Intellectual," Macalester International: Vol. 3, Article 7. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl/vol3/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for Global Citizenship at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Macalester International by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 04/18/96 3:53 PM 1880sai2.qxd THE LIMITS OF THE ARTISTIC IMAGINATION, AND THE SECULAR INTELLECTUAL Edward W. Said Poetry is one of the things we do to our ignorance; criticism makes us conscious of what we have done, and sometimes makes us conscious of what can be done next, or done again. R. P. Blackmur1 I. Literary Worlds In her fine new book, Writing and Being, Nadine Gordimer argues that the modern writer uses fiction to enact life, to explore worlds that are concealed in the turmoil of everyday reality, to investigate politics that are otherwise forbidden or ignored. For her, writers like Naguib Mahfouz, Chinua Achebe, and Amos Oz are witnesses to a struggle for truth and freedom, their -

Das Reich Der Seele Walther Rathenau’S Cultural Pessimism and Prussian Nationalism ~ Dieuwe Jan Beersma

Das Reich der Seele Walther Rathenau’s Cultural Pessimism and Prussian Nationalism ~ Dieuwe Jan Beersma 16 juli 2020 Master Geschiedenis – Duitslandstudies, 11053259 First supervisor: dhr. dr. A.K. (Ansgar) Mohnkern Second supervisor: dhr. dr. H.J. (Hanco) Jürgens Abstract Every year the Rathenau Stiftung awards the Walther Rathenau-Preis to international politicians to spread Rathenau’s ideas of ‘democratic values, international understanding and tolerance’. This incorrect perception of Rathenau as a democrat and a liberal is likely to have originated from the historiography. Many historians have described Rathenau as ‘contradictory’, claiming that there was a clear and problematic distinction between Rathenau’s intellectual theories and ideas and his political and business career. Upon closer inspection, however, this interpretation of Rathenau’s persona seems to be fundamentally incorrect. This thesis reassesses Walther Rathenau’s legacy profoundly by defending the central argument: Walther Rathenau’s life and motivations can first and foremost be explained by his cultural pessimism and Prussian nationalism. The first part of the thesis discusses Rathenau’s intellectual ideas through an in-depth analysis of his intellectual work and the historiography on his work. Motivated by racial theory, Rathenau dreamed of a technocratic utopian German empire led by a carefully selected Prussian elite. He did not believe in the ‘power of a common Europe’, but in the power of a common German Europe. The second part of the thesis explicates how Rathenau’s career is not contradictory to, but actually very consistent with, his cultural pessimism and Prussian nationalism. Firstly, Rathenau saw the First World War as a chance to transform the economy and to make his Volksstaat a reality. -

Princeton University Press Spring 2016 Catalog

Histories of Ornament From Global to Local EditED by GÜLRU NEcipOĞlu & AliNA PAYNE This lavishly illustrated volume is the first major global history of orna- ment from the Middle Ages to today. Crossing historical and geograph- ical boundaries in unprecedented ways and considering the role of ornament in both art and architecture, Histories of Ornament offers a nuanced examination that integrates medieval, Renaissance, baroque, and modern Euroamerican traditions with their Islamic, Indian, Chi- nese, and Mesoamerican counterparts. At a time when ornament has A groundbreaking exploration of re-emerged in architectural practice and is a topic of growing interest to art and architectural historians, the book reveals how the long his- the global significance of ornament tory of ornament illuminates its global resurgence today. in art and architectural history Organized by thematic sections on the significance, influence, and role of ornament, the book addresses ornament’s current revival in architecture, its historiography and theories, its transcontinental mobility in medieval and early modern Europe and the Middle East, “Histories of Ornament will propel art and its place in the context of industrialization and modernism. historical consideration of ornament Throughout, Histories of Ornament emphasizes the portability and to new levels. No other volume so politics of ornament, figuration versus abstraction, cross-cultural dia- clearly shows the profound relevance logues, and the constant negotiation of local and global traditions. of medieval and early modern Featuring original essays by more than two dozen scholars from ornament, and the surprising cross- around the world, this authoritative and wide-ranging book provides an cultural aspects of their histories, indispensable reference on the histories of ornament in a global context. -

Australian Politicians

Asem Judeh Melbourne 19 October 2009 The Hon Arch Bevis MP Chair Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Mr Bevis Supplementary Submission on re-listing Hamas’s Brigades and PIJ As you know the politics of Israel-Palestine issue is always attracting the international community attention and always there are important development day-to-day basis. Because of that I am writing this supplementary submission that summarises the important developments in relation to re-listing the Brigades and PIJ since I submitted my original submission to PJCIS. The recent development supports all the facts, analysis and serious allegations included in my previous submission. These recent facts and reports show clearly the root causes of the violence and terrorism in Palestine. It proves that occupation is violence and terrorism; colonization is violence and terrorism. This new evidence proves that ASIO’s assessment report is politically motivated and misleading the parliament and public. Finally, when I appear before the Committee to give oral evidence, I will present more facts and answer all clarifications and questions from the Committee members. Sincerely yours, Asem Judeh Supplementary Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security Review of the re-listing of Hamas' Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades and PIJ Page: 1 of 1 Asem Judeh’s Supplementary Submission on re-listing Hamas’s Brigades and PIJ 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 4 2. UN FACT FINDINGS MISSION ON THE GAZA CONFLICT ................ 4 WHY UN FACT FINDINGS MISSION ON THE GAZA CONFLICT REPORT IS RELATED TO PJCIS INQUIRY? .................................................................................................... 5 ISRAEL AND HAMAS RESPONSE TO UN FACT FINDING MISSION AND UNHR DECISION ENDORSING THE REPORT, OCTOBER 16. -

The German-Jewish Experience Revisited Perspectives on Jewish Texts and Contexts

The German-Jewish Experience Revisited Perspectives on Jewish Texts and Contexts Edited by Vivian Liska Editorial Board Robert Alter, Steven E. Aschheim, Richard I. Cohen, Mark H. Gelber, Moshe Halbertal, Geoffrey Hartman, Moshe Idel, Samuel Moyn, Ada Rapoport-Albert, Alvin Rosenfeld, David Ruderman, Bernd Witte Volume 3 The German-Jewish Experience Revisited Edited by Steven E. Aschheim Vivian Liska In cooperation with the Leo Baeck Institute Jerusalem In cooperation with the Leo Baeck Institute Jerusalem. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-037293-9 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-036719-5 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-039332-3 ISSN 2199-6962 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover image: bpk / Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin Typesetting: PTP-Berlin, Protago-TEX-Production GmbH, Berlin Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Preface The essays in this volume derive partially from the Robert Liberles International Summer Research Workshop of the Leo Baeck Institute Jerusalem, 11–25 July 2013. -

German Historical Institute London Bulletin Vol 23 (2001), No. 1

German Historical Institute London Bulletin Volume XXIII, No. 1 May 2001 CONTENTS Seminars 3 Review Article Raiding the Storehouse of European Art: National Socialist Art Plunder during the Second World War (Ines Schlenker) 5 Debate Stefan Berger responds to Ulrich Muhlack 21 Book Reviews I. S. Robinson, Henry IV of Germany, 1056-1106 (Hanna Vollrath) 34 Gerd Althoff, Spielregeln der Politik im Mittelalter: Kommuni- kation in Frieden und Fehde (Timothy Reuter) 40 William Gervase Clarence-Smith, Cocoa and Chocolate, 1765-1914 (Andreas Eckert) 48 L. G. Mitchell, Lord Melbourne 1779-1848 (Patrick Bahners) 53 Wolfgang Piereth, Bayerns Pressepolitik und die Neuordnung Deutschlands nach den Befreiungskriegen (Michael Rowe) 65 Margit Szöllösi-Janze, Fritz Haber 1868-1934: Eine Biographie (Raymond Stokes) 71 Gesine Krüger, Kriegsbewältigung und Geschichtsbewußtsein: Realität, Deutung und Verarbeitung des deutschen Kolonial- kriegs in Namibia 1904 bis 1907 (Tilman Dedering) 76 Contents Kurt Flasch, Die geistige Mobilmachung: Die deutschen Intellektuellen und der Erste Weltkrieg. Ein Versuch (Roger Chickering) 80 Notker Hammerstein, Die Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft in der Weimarer Republik und im Dritten Reich: Wissenschafts- politik in Republik und Diktatur; Michael Fahlbusch, Wissen- schaft im Dienst der nationalsozialistischen Politik? Die ‘Volksdeutschen Forschungsgemeinschaften’ von 1931-1945 (Paul Weindling) 83 Peter Strunk, Zensur und Zensoren: Medienkontrolle und Propagandapolitik unter sowjetischer Besatzungsherrschaft in Deutschland (Patrick Major) 89 Paul Nolte, Die Ordnung der deutschen Gesellschaft: Selbstent- wurf und Selbstbeschreibung im 20. Jahrhundert (Thomas Rohrkrämer) 93 Noticeboard 98 Library News 111 Recent Acquisitions 2 SEMINARS AT THE GHIL SUMMER 2001 15 May PROFESSOR GÜNTHER HEYDEMANN (Leipzig) The Revolution of 1989/90 in the GDR—Recent Research Günther Heydemann has published widely on European history of the nineteenth century and the twentieth-century German dictator- ships.