IST Battlefields Trip 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RENFORCEMENTS DE CHAUSSEE SUR ROUTES DEPARTEMENTALES Annexe 1 Programme 2019

RENFORCEMENTS DE CHAUSSEE SUR ROUTES DEPARTEMENTALES Annexe 1 programme 2019 Année nature Longueur Coût Montant Trafic 2017 en Canton N° RD Classe Localisation dernier revêt. PR début PR Fin Surface m2 Nature travaux Observations ml unitaire en euros TTC V/j revêt. existant ABBEVILLE 2 / MARTAINNEVILLE / TOURS-EN-VIMEU 2001 ES 5558 dont 29 1 19+807 21+027 1 220 14 000 BBSG 22,00 310 000 Arrachement des matériaux GAMACHES Echangeur A28 2002 BB 10 % de PL 950 dont Faïençage et pelade ALBERT 11 2 MARIEUX 1997 ES 23+133 23+898 765 5 000 BBSG 24,00 120 000 7 % de PL Continuité d’itinéraire 2351 dont ALBERT 42 2 MORLANCOURT 1998 ES 5+586 6+598 1 022 7 000 BBSG 20,00 140 000 Pelade localisée et faïençage 5 % de PL 2920 dont DOULLENS 925 1 FIENVILLERS 1993 ES 56+004 57+048 1 077 7 800 EME + BBSG 55,00 450 000 11 % de PL Usure du revêtement Pelade Départ de matériaux BERNAVILLE (Partie Sud) 2920 dont DOULLENS 925 1 2002 BB 51+722 52+611 898 6 500 BBSG 24,00 185 000 De la RD 99 / Direction FIENVILLERS 11 % de PL DOULLENS / 10 GB+BBSG 1316 dont 216 2 BERNEUIL / DOMART-EN-PONTHIEU 2008 ES 4+865 8+313 3 453 25 000 60,00 1 600 000 FLIXECOURT Poutres 13 % de PL Ornièrage significatif en rives Défaut d’adhérence généralisé Fissures longitudinales Carrefour RD 12 / RD 216 à la sortie Reconstruction de 1316 dont FLIXECOURT 216 2 d’agglomération de DOMART-EN- 2008 ECF 8+313 8+738 425 2 550 110,00 290 000 chaussée 13 % de PL PONTHIEU Reconstruction 1995 BB 3560 dont Ornièrage HAM 1017 1 MARCHELEPOT 25+694 26+928 1 238 9 600 partielle et 60,00 580 000 1997 -

The Western Front;

The Western Front Drawings by Muirhead Bone PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF THE WAR OFFICE FROM THE OFFICES OF "COUNTRY LIFE" LTD 20 TAVISTOCK STREET COVENT GARDEN LONDON MCMXVII GENERAL SIR DOUGLAS HAIG, GCB, GCVO, KCIE. GRAND PLACE AND RUINS OF THE CLOTH HALL, YPRES The gaunt emptiness of Ypres is expressed in this drawing, done from the doorway of a ruined church in a neighbouring square. The grass has grown long this summer on the Grand Place and is creeping up over the heaps of ruins. The only continuous sound in Ypres is that of birds, which sing in it as if it were country. A STREET IN YPRES In the distance is seen what remains of the Cloth Hall. On the right a wall long left unsupported is bending to its fall. The crash of such a fail is one of the few sounds that now break the silence of Ypres, where the visitor starts at the noise of a distant footfall in the grass-grown streets. DISTANT VIEW OF YPRES The Ypres salient is here seen from a knoll some six miles south-west of the city, which is marked, near the centre of the drawing, by the dominant ruin of the cathedral. The German front line is on the heights beyond, Hooge being a little to the spectator’s right of the city and Zillebeke slightly more to the right again. Dickebusch lies about half way between the eye and Ypres. The fields in sight are covered with crops, varied by good woodland. To a visitor coming from the Somme battlefield the landscape looks rich and almost peaceful. -

GUERRE 1914 – 1918 Mcmaster U

Sources : GUERRE 1914 – 1918 McMaster U. / Trench Maps / Albert, Bray-sur-Somme : Somme Battlefield, Fricourt & Mametz / Sheet 62D NE / Edition 2B / 25.04.1916 ; McMaster U. / Trench Maps / Albert, Bray-sur-Somme : Somme Battlefield, Fricourt & Mametz / Sheet 62D NE / Edition 2D (local) / 30.04.1918 ; 1/4 L’AMPLEUR DES TRAVAUX D’ADAPTATION DU RESEAU FERROVIAIRE IWM /Q 58527 / Unidentified22 aerial juillet photograph 1918 of the Morlancourt area dated 22nd July 1918 ; IWM / Q 915 / 12Inch Mark IX gun of the Royal Garrison Artillery on railway mounting at Méaulte / September 1916 ; IWM / Q 46929 / Dernancourt – Méaulte Line / Wreckage of bridge over River Ancre destroyed by British March 1918 / September 1918 ; Front de la Somme : La ligne nouvelle Dernancourt / Maricourt (80) IGN / Remonter le Temps / clichés du 31 août 1947. 31 août 1947 Vers Albert MEAULTE 25 avril 1916 30 avril 1918 Ligne n°272 000 Vers Amiens DERNANCOURT 1 22 juillet 1918 MORLANCOURT E. FACON / V1 / Etabli le 14.02.2020 & modifié le 21.11.2020 Dernancourt, septembre 1918 1 Méaulte, septembre 1916 Diffusable SNCF RESEAU 25 avril 1916 GUERRE 1914 – 1918 2/4 L’AMPLEUR DES TRAVAUX D’ADAPTATION DU RESEAU FERROVIAIRE Front de la Somme : La ligne nouvelle Dernancourt / Maricourt (80) 30 avril 1918 31 août 1947 E. FACON / V1 / Etabli le 14.02.2020 & modifié le 21.11.2020 28 mai 1918 Sources : McMaster U. / Trench Maps / Albert, Bray-sur-Somme : Somme Battlefield, Fricourt & Mametz / Sheet 62D NE / Edition 2B / 25.04.1916 ; McMaster U. / Trench Maps / Albert, Bray-sur-Somme : Somme Battlefield, Fricourt & Mametz / Sheet 62D NE / Edition 2D (local) / 30.04.1918 ; NLS / Trench Maps / Sheet 62D NE / Edition 2E / Published May 1918 / Trenches corrected to 28 May 1918 ; Diffusable SNCF RESEAU IGN / Remonter le Temps / clichés du 31 août 1947. -

Yorkshire and the First Day of the Somme

This is a repository copy of Yorkshire and the First Day of the Somme. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/99480/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Spiers, EM (2016) Yorkshire and the First Day of the Somme. Northern History, 53 (2). pp. 249-266. ISSN 0078-172X https://doi.org/10.1080/0078172X.2016.1195601 © 2016, University of Leeds. This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Northern History on Sep 2016, available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0078172X.2016.1195601. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 YORKSHIRE AND THE FIRST DAY OF THE SOMME EDWARD M. -

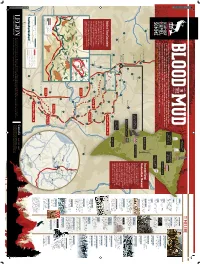

Beaumont-Hamel and the Battle of the Somme, Onwas Them, Trained a Few and Most Were Minutes Within Killed of the Assault

2015-12-18 2:03 PM Hunter’s CWGC TIMELINE Cemetery 1500s June 1916 English fishermen establish The regiment trains seasonal camps in Newfoundland in the rain and mud, waiting for the start of the Battle of the Somme 1610 The Newfoundland Company June 28, 1916 Hawthorn 51st (Highland) starts a proprietary colony at Cuper’s Cove near St. John’s The regiment is ordered A century ago, the Newfoundland Regiment suffered staggering losses at Beaumont-Hamel in France Ridge No. 2 Division under a mercantile charter to move to a forward CWGC Cemetery Monument granted by Queen Elizabeth I trench position, but later at the start of the Battle of the Somme on July 1, 1916. At the moment of their attack, the Newfoundlanders that day the order is postponed July 23-Aug. 7, 1916 were silhouetted on the horizon and the Germans could see them coming. Every German gun in the area 1795 Battle of Pozières Ridge was trained on them, and most were killed within a few minutes of the assault. German front line Newfoundland’s first military regiment is founded 9:15 p.m., June 30 September 1916 For more on the Newfoundland Regiment, Beaumont-Hamel and the Battle of the Somme, to 2 a.m., July 1, 1916 Canadian troops, moved from go to www.legionmagazine.com/BloodInTheMud. 1854 positions near Ypres, begin Newfoundland becomes a crown The regiment marches 12 kilo- arriving at the Somme battlefield Y Ravine CWGC colony of the British Empire metres to its designated trench, Cemetery dubbed St. John’s Road Sept. -

The Battle of the Somme

THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME FIRST PHASE BY JOHN BUCHAN THOMAS NELSON ft SONS, LTD., 35 & 36, PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON, E.C. EDINBURGH. NEW VORK. 4 PARIS. 1922 — THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME.* CHAPTER I. PRELIMINARIES. ROM Arras southward the Western battle- front leaves the coalpits and sour fields F of the Artois and enters the pleasant region of Picardy. The great crook of the upper Somme and the tributary vale of the Ancre intersect a rolling tableland, dotted with little towns and furrowed by a hundred shallop chalk streams. Nowhere does the land rise higher than 500 feet, but a trivial swell—such is the nature of the landscape jxfay carry the eye for thirty miles. There are few detached farms, for it is a country of peasant cultivators who cluster in villages. Not a hedge breaks the long roll of eomlands, and till the higher ground is reached the lines of tall poplars flanking the great Roman highroads are the chief landmarks. At the lift of country between Somme and Ancre copses patch tlje slopes, and the BATTLE OF THE SOMME. sometimes a church spire is seen above the trees winds iron) some woodland hamlet* The Somme faithfully in a broad valley between chalk bluffs, •dogged by a canal—a curious river which strains, “ like; the Oxus, through matted rushy isles,” and is sometimes a lake and sometimes an expanse of swamp, The Ancre is such a stream as may be found in Wiltshire, with good trout in, its pools. On a hot midsummer day the slopes are ablaze with yellow mustard, red poppies and blue cornflowers ; and to one coming from the lush flats of Flanders, or the “ black country ” of the Pas dc Calais, or the dreary levels of Champagne, or the strange melancholy Verdun hills, this land wears a habitable and cheerful air, as if remote from the oppression of war. -

Circuit Du Saillant De Fricourt Et Du Lochnagar Crater

n°20 Circuit du Saillant de Fricourt et du Lochnagar Crater. Fricourt- Bécourt (Bécordel-Bécourt) - La Boisselle (Ovillers-la-Boisselle) Durée : 3 h + 2 h Distance : 12 km (les Bretons) + 6 km (le bois français côte 110 et la citadelle) Départ : place de Fricourt En venant d’Amiens, - 5318 : www.grandnord.fr conception prendre la D929 vers Albert puis la rocade vers la D938. 1 En face du Monument aux Morts, prendre cendre jusqu’à l’église par la rue de la 34e cimetière britannique où est enterré le à droite, après la salle des fêtes, la rue du Division. Voir la pâture avec des trous de Major Raper. Continuer pour passer au Major Raper. Passer devant une fontaine mines appelés l’Îlot ou Glory Hole, lieu croisement de l’ancienne route Albert- blanche qui se trouve sur la droite. Prendre de combat du 19e R.I. Breton. Péronne, appelée Chaussée Brunehaut à gauche à la fourche. Passer devant la 3 A partir du triangle, emprunter le chemin (Soissons-Sangatte). Quitter la ferme sur boulangerie jusqu’à l’église et la mairie. de terre sur la gauche sur environ 300m la droite, puis tout droit. Le Major Raper est un officier britanni- puis à gauche et à droite en direction du 6 Tourner à droite, prendre le second que tué dans le bois de Fricourt le 2 juillet Lochnagar Crater. Ce Trou de mine est chemin à gauche jusque la D 147, puis à 1916 lors de l’offensive de la Somme. réalisé par les britanniques et a explosé droite jusqu’au rond-point. -

18) 16753 Private Arthur POPEJOY

18) 16753 Private Arthur POPEJOY Kia 3/07/16 5th Bn Royal Berkshire Regiment Awarded : British War Medal Victory Medal Date arrived in theatre of war : France, not known Born Aldermaston Enlisted Newbury It is not possible to say with certainty when Arthur Popejoy joined his unit, the 5 th Royal Berkshire, out in France. He was not awarded the 1914-15 campaign Star and thus his arrival must have taken place sometime after 1/1/1916. The battalion had been out in France since June 1915. However, January to June 1916 saw the 5 th Royal Berkshire holding the line in the Bethune sector. Following the Battle of Loos in September-October 1915, this had been a fairly quiet sector apart from trench-raiding that had become a particular feature at this period. The 5 th Royal Berkshire moved down to the Somme area (Albert) on 16 th June 1916 by train from Lillers. Here they remained in the rear areas (Franvillers) training for the large Somme offensive that would begin on 1 st July. They would miss the slaughter of the first day itself, but would be brought up to the front line within 48 hours. The sector they would be brought to would be the lines in front of the village of Ovillers la Boisselle. This and the neighbouring village of La Boisselle had been the objectives of the 34 th Division (Kitchener battalions, all from Tyneside), neither had been taken - the width of No-man’s land had been at its widest here, the line of advance had been up two valleys termed ‘Sausage’ and ‘Mash’, all the troops had advanced together in one attack. -

Dawe, Frederick

Private Frederick Dawe (Regimental Number 3334), having no known last resting-place, is commemorated on the bronze beneath the Caribou in the Newfoundland Memorial Park at Beaumont- Hamel. His occupation prior to military service recorded as that of a fisherman and miner, Frederick Dawe was a volunteer of the Eleventh Recruitment Draft. He presented himself for medical examination on December 14 of 1916 at the Church Lads Brigade Armoury* in St. John’s, capital city of the Dominion of Newfoundland. It was a procedure which was to pronounce him as…Fit for Foreign Service. *The building was to serve as the Regimental Headquarters in Newfoundland for the duration of the conflict. It was to be on the day of that medical assessment, December 14, and at the same venue, that Frederick Dawe would enlist. He was thus engaged…for the duration of the war*…at the daily private soldier’s rate of a single dollar to which was to be appended a ten-cent per diem Field Allowance. *At the outset of the War, perhaps because it was felt by the authorities that it would be a conflict of short duration, the recruits enlisted for only a single year. As the War progressed, however, this was obviously going to cause problems and the men were encouraged to re-enlist. Later recruits – as of or about May of 1916 - signed on for the ‘Duration’ at the time of their original enlistment. Only some few hours were now to follow before there then came to pass, while still at the CLB Armoury on Harvey Road, the final formality of his enlistment: attestation. -

The Durham Light Infantry and the Somme 1916 Contents

The Durham Light Infantry and The Somme 1916 Contents Part 1: Introduction and Background Notes leading up to the Battle of the Somme. 1.1: Introduction. 1.2: The background to the Battle of the Somme, 1 July – 18 November 1916. 1.3: The Organisation of the Fourth Army, including the composition of Divisions and Brigades in which the DLI Battalions served. 1.4: Battles, Tactical Incidents and Subsidiary Attacks. Part 2: The Battles and Actions in which the Sixteen Battalions of The Durham Light Infantry were involved. 2.1: 1 - 13 July 1916. The Battle of Albert and the Capture of Contalmaison. 2.2: 14 - 17 July 1916. The Battle of Bazentin Ridge. 2.3: 14 July - 3 September 1916. The Battle of Delville Wood. 2.4: 14 July - 7 August 1916. The Battle of Pozières Ridge. 2.5: 3 - 6 September 1916. The Battle of Guillemont. 2.6: 15 - 22 September 1916. The Battle of Flers-Courcelette. 2.7: 25 - 28 September 1916. The Battle of Morval. 2.8: 1 - 18 October 1916. The Battle of Le Transloy Ridges. 2.9: 23 October - 5 November 1916. Fourth Army Operations. 2.10: 13 - 18 November 1916. The Battle of the Ancre. 1 Part 3: The Awards for Distinguished Conduct and Gallantry. 3.1: Notes and analysis of Awards for gallantry on the Somme. 3.2: The Victoria Cross, the Distinguished Service Order and the Military Cross awarded to Officers of the DLI for gallantry on the Somme 1916. 3.2.1: The Victoria Cross. 3.2.2: The Distinguished Service Order. -

British 21 Infantry Division on the Western Front 1914

Centre for First World War Studies BRITISH 21ST INFANTRY DIVISION ON THE WESTERN FRONT 1914 - 1918 A CASE STUDY IN TACTICAL EVOLUTION by KATHRYN LOUISE SNOWDEN A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Modern History School of Historical Studies The University of Birmingham March 2001 i University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This MPhil thesis is a case study of the British 21st Infantry Division on the Western Front during the First World War. It examines the progress of the division, analysing the learning curve of tactical evolution that some historians maintain was experienced by the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). 21st Division was a New Army division, typical of those raised after the declaration of war, and its performance throughout the war may be regarded as indicative of the progress or otherwise of these units within the BEF. The conclusions are drawn through an assessment of 21st Division in four battles during the war. The achievements of the division are analysed using a series of performance indicators, taking into account variables such as the weather, the terrain, and the enemy. -

Première Guerre Mondiale Dans La Somme, Une Très Grande Réussite

r i n e v u o S PREMIÈRE GUERRE MONDIALE Commémorer le Centenaire dans la Somme Janvier 2014 PRÉFET DE LA SOMME Sommaire Editorial du préfet 3 Editorial du président du Conseil général 4 1. L’histoire de la Grande Guerre dans la Somme 5 Un bref rappel historique de la Grande Guerre 6 Les combats dans la Somme 7 2. Commémorer dans la Somme 10 Les enjeux de la commémoration 11 La préparation du centenaire dans la Somme 12 3. Les projets retenus dans la Somme 13 Les 27 projets retenus par le comité départemental 14 Le calendrier des événements 25 Les appels à projets 28 2 Éditorial du préfet De 2014 à 2018, le monde entier commémo - La deuxième bataille de la Somme, qui a débuté rera le centenaire de la Première Guerre le 1 er juillet 1916 pour se terminer mi-novembre de mondiale. Cette commémoration constituera la même année, a engendré des pertes considé - à l’évidence un événement majeur pour la France, et en particulier pour la Somme. rables. Mais elle a permis aux français de tenir à Verdun, et prit ainsi une importance décisive dans Dans ce département fortement marqué par la suite de ce conflit. de terribles combats, la mémoire de la Grande Guerre, sans doute plus qu’ailleurs, a La commémoration de la Grande Guerre revêt façonné les paysages et l’identité des terri - donc une importance particulière dans le dépar - toires, et imprègne encore aujourd’hui les tement de la Somme où le tourisme de mémoire, femmes et les hommes qui y vivent.