Dawe, Frederick

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Colours Part 1: the Regular Battalions

The Colours Part 1: The Regular Battalions By Lieutenant General J. P. Riley CB DSO PhD MA FRHistS 1. The Earliest Days At the time of the raising of Lord Herbert’s Regiment in March 1689,i it was usual for a regiment of foot to hold ten Colours. This number corre- sponded to the number of companies in the regiment and to the officers who commanded these companies although the initial establishment of Herbert’s Regiment was only eight companies. We have no record of the issue of any Colours to Herbert’s Regiment – and probably the Colo- nel paid for their manufacture himself as he did for much of the dress and equipment of his regiment. What we do know however is that each Colour was the rallying point for the company in battle and the symbol of its esprit. Colours were large – generally six feet square although no regulation on size yet existed – so that they could easily be seen in the smoke of a 17th Century battlefield for we must remember that before the days of smokeless powder, obscuration was a major factor in battle. So too was the ability of a company to keep its cohesion, deliver effec- tive fire and change formation rapidly either to attack, defend, or repel cavalry. A company was made up of anywhere between sixty and 100 men, with three officers and a varying number of sergeants, corporals and drummers depending on the actual strength. About one-third of the men by this time were armed with the pike, two-thirds with the match- lock musket. -

Fops Under Fire: British Drum-Majors in Action During the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleon Series Fops under Fire: British Drum-Majors in Action during the Napoleonic Wars By Eamonn O’Keeffe In the performance theatre of the early nineteenth-century British military spectacle, drum- majors took centre stage. Sporting cocked hats and silver-tipped canes, these princes of pomp and circumstance uncased and lodged the regimental colours for parade and marched at the head of the battalion during reviews and inspections. “It should never be objected”, wrote Captain Bennet Cuthbertson, that a drum-major was “too great a coxcomb”, using a contemporary synonym for a dandy. On the contrary, a drum-major’s dress should promote vanity and self-importance, for it was “absolutely necessary for him to strut, and think himself a man of consequence” when leading his drummers on parade.1 A drum-major’s appearance was a source of regimental pride. According to a 1782 satirical work, this foppish figure was “the Paris, if not the Adonis” of a battalion, for “every judge of discipline will estimate the goodness of the corps by the taste and splendor of [his] trappings.”2 Unsurprisingly, the prestige associated with well-dressed drum-majors encouraged lavish expenditure; in 1813 the 1st Devon Militia paid the eye-watering sum of seventeen pounds, six shillings and eight pence for their “drum-major’s suit”, ceremonial baldric and “fine silver-laced hat” – more than six times the cost of an ordinary drummer’s cap and coat.3 This bill excluded the price of the drum-major’s finely engraved silver-mounted staff or cane, often almost as tall or taller than its wielder.4 Yet such showy extravagance sometimes caused confusion. -

Museum's 50Th Year at Alnwick Castle St George's Day 2020 Friends Of

St George’s Friends of The Day 2020 St George’s Day Greetings from the Fusiliers Museum of Northumberland Museum’s 50th Year at Alnwick Castle Marching Orders: From Fenham Barracks to Alnwick Castle 50 years ago It's ironic to be celebrating the Museum's 50th Anniversary at Alnwick Castle while the Museum, in common with all museums, is closed for an uncertain period. But sixty years ago it looked as if the Museum might close for good. Lt Colonel Reggie Pratt, who was Honorary Curator of the Museum for twenty-five years, from 1960 to 1985, tells the story in a briefing document he wrote when he retired. He explains that the Museum was established in the Regimental Depot at Fenham Barracks, in 1929. But by 1960 it had become clear the Museum would have to leave the Barracks. 'All attempts to find a permanent home in Newcastle having failed, the Duke of Northumberland was approached and kindly made the Abbot’s Tower available at Alnwick Castle.' The Army Museums Ogilby Trust employed a professional to design and install the displays, and the Museum opened at the Castle in 1970. Behind the walls of a Regimental Depot is not an easy location for visitor access. However Colonel Pratt writes that Alnwick Castle is 'a major attraction for visitors'; at the Museum 'Some 5,000 visitors are expected during the year'. He would be astounded to know that in 2019 the Museum had 91,214 visitors, in normal times a typical year. But he has a warning: 'There is a danger that MOD funding might be withdrawn at some time in the future'; it was, finally, over thirty years later, in 2017. -

RENFORCEMENTS DE CHAUSSEE SUR ROUTES DEPARTEMENTALES Annexe 1 Programme 2019

RENFORCEMENTS DE CHAUSSEE SUR ROUTES DEPARTEMENTALES Annexe 1 programme 2019 Année nature Longueur Coût Montant Trafic 2017 en Canton N° RD Classe Localisation dernier revêt. PR début PR Fin Surface m2 Nature travaux Observations ml unitaire en euros TTC V/j revêt. existant ABBEVILLE 2 / MARTAINNEVILLE / TOURS-EN-VIMEU 2001 ES 5558 dont 29 1 19+807 21+027 1 220 14 000 BBSG 22,00 310 000 Arrachement des matériaux GAMACHES Echangeur A28 2002 BB 10 % de PL 950 dont Faïençage et pelade ALBERT 11 2 MARIEUX 1997 ES 23+133 23+898 765 5 000 BBSG 24,00 120 000 7 % de PL Continuité d’itinéraire 2351 dont ALBERT 42 2 MORLANCOURT 1998 ES 5+586 6+598 1 022 7 000 BBSG 20,00 140 000 Pelade localisée et faïençage 5 % de PL 2920 dont DOULLENS 925 1 FIENVILLERS 1993 ES 56+004 57+048 1 077 7 800 EME + BBSG 55,00 450 000 11 % de PL Usure du revêtement Pelade Départ de matériaux BERNAVILLE (Partie Sud) 2920 dont DOULLENS 925 1 2002 BB 51+722 52+611 898 6 500 BBSG 24,00 185 000 De la RD 99 / Direction FIENVILLERS 11 % de PL DOULLENS / 10 GB+BBSG 1316 dont 216 2 BERNEUIL / DOMART-EN-PONTHIEU 2008 ES 4+865 8+313 3 453 25 000 60,00 1 600 000 FLIXECOURT Poutres 13 % de PL Ornièrage significatif en rives Défaut d’adhérence généralisé Fissures longitudinales Carrefour RD 12 / RD 216 à la sortie Reconstruction de 1316 dont FLIXECOURT 216 2 d’agglomération de DOMART-EN- 2008 ECF 8+313 8+738 425 2 550 110,00 290 000 chaussée 13 % de PL PONTHIEU Reconstruction 1995 BB 3560 dont Ornièrage HAM 1017 1 MARCHELEPOT 25+694 26+928 1 238 9 600 partielle et 60,00 580 000 1997 -

The Western Front;

The Western Front Drawings by Muirhead Bone PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF THE WAR OFFICE FROM THE OFFICES OF "COUNTRY LIFE" LTD 20 TAVISTOCK STREET COVENT GARDEN LONDON MCMXVII GENERAL SIR DOUGLAS HAIG, GCB, GCVO, KCIE. GRAND PLACE AND RUINS OF THE CLOTH HALL, YPRES The gaunt emptiness of Ypres is expressed in this drawing, done from the doorway of a ruined church in a neighbouring square. The grass has grown long this summer on the Grand Place and is creeping up over the heaps of ruins. The only continuous sound in Ypres is that of birds, which sing in it as if it were country. A STREET IN YPRES In the distance is seen what remains of the Cloth Hall. On the right a wall long left unsupported is bending to its fall. The crash of such a fail is one of the few sounds that now break the silence of Ypres, where the visitor starts at the noise of a distant footfall in the grass-grown streets. DISTANT VIEW OF YPRES The Ypres salient is here seen from a knoll some six miles south-west of the city, which is marked, near the centre of the drawing, by the dominant ruin of the cathedral. The German front line is on the heights beyond, Hooge being a little to the spectator’s right of the city and Zillebeke slightly more to the right again. Dickebusch lies about half way between the eye and Ypres. The fields in sight are covered with crops, varied by good woodland. To a visitor coming from the Somme battlefield the landscape looks rich and almost peaceful. -

Tolkien and the Zeppelins

Journal of Tolkien Research Volume 11 Issue 1 Article 1 2020 Tolkien and the Zeppelins Seamus Hamill-Keays none, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Hamill-Keays, Seamus (2020) "Tolkien and the Zeppelins," Journal of Tolkien Research: Vol. 11 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/vol11/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Christopher Center Library at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Tolkien Research by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Tolkien and the Zeppelins Cover Page Footnote I am immensely grateful to those who have helped in the preparation of this article: Dr Nancy Bunting for her encouragement to write it, Ruth Lacon for her extensive knowledge of RNAS airships, Ian Castle for permission to include an extract from his website, Helen Clark of East Riding Archives, Dr Rebecca Harding of the Imperial War Museum Duxford, Willis Ainley for the photograph of Roos Post Office and the many others whose diligent research listed in the references provided me with details that support this article. This article is available in Journal of Tolkien Research: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/vol11/iss1/ 1 Hamill-Keays: Tolkien and the Zeppelins TOLKIEN AND THE ZEPPELINS Seamus Hamill-Keays Squadron Leader, Royal Air Force (Retired) 1.Introduction The tumults in the killing fields of the Great War died away over one hundred years ago, yet the Western Front still echoes in memories in Britain and Ireland. -

GUERRE 1914 – 1918 Mcmaster U

Sources : GUERRE 1914 – 1918 McMaster U. / Trench Maps / Albert, Bray-sur-Somme : Somme Battlefield, Fricourt & Mametz / Sheet 62D NE / Edition 2B / 25.04.1916 ; McMaster U. / Trench Maps / Albert, Bray-sur-Somme : Somme Battlefield, Fricourt & Mametz / Sheet 62D NE / Edition 2D (local) / 30.04.1918 ; 1/4 L’AMPLEUR DES TRAVAUX D’ADAPTATION DU RESEAU FERROVIAIRE IWM /Q 58527 / Unidentified22 aerial juillet photograph 1918 of the Morlancourt area dated 22nd July 1918 ; IWM / Q 915 / 12Inch Mark IX gun of the Royal Garrison Artillery on railway mounting at Méaulte / September 1916 ; IWM / Q 46929 / Dernancourt – Méaulte Line / Wreckage of bridge over River Ancre destroyed by British March 1918 / September 1918 ; Front de la Somme : La ligne nouvelle Dernancourt / Maricourt (80) IGN / Remonter le Temps / clichés du 31 août 1947. 31 août 1947 Vers Albert MEAULTE 25 avril 1916 30 avril 1918 Ligne n°272 000 Vers Amiens DERNANCOURT 1 22 juillet 1918 MORLANCOURT E. FACON / V1 / Etabli le 14.02.2020 & modifié le 21.11.2020 Dernancourt, septembre 1918 1 Méaulte, septembre 1916 Diffusable SNCF RESEAU 25 avril 1916 GUERRE 1914 – 1918 2/4 L’AMPLEUR DES TRAVAUX D’ADAPTATION DU RESEAU FERROVIAIRE Front de la Somme : La ligne nouvelle Dernancourt / Maricourt (80) 30 avril 1918 31 août 1947 E. FACON / V1 / Etabli le 14.02.2020 & modifié le 21.11.2020 28 mai 1918 Sources : McMaster U. / Trench Maps / Albert, Bray-sur-Somme : Somme Battlefield, Fricourt & Mametz / Sheet 62D NE / Edition 2B / 25.04.1916 ; McMaster U. / Trench Maps / Albert, Bray-sur-Somme : Somme Battlefield, Fricourt & Mametz / Sheet 62D NE / Edition 2D (local) / 30.04.1918 ; NLS / Trench Maps / Sheet 62D NE / Edition 2E / Published May 1918 / Trenches corrected to 28 May 1918 ; Diffusable SNCF RESEAU IGN / Remonter le Temps / clichés du 31 août 1947. -

Yorkshire and the First Day of the Somme

This is a repository copy of Yorkshire and the First Day of the Somme. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/99480/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Spiers, EM (2016) Yorkshire and the First Day of the Somme. Northern History, 53 (2). pp. 249-266. ISSN 0078-172X https://doi.org/10.1080/0078172X.2016.1195601 © 2016, University of Leeds. This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Northern History on Sep 2016, available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0078172X.2016.1195601. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 YORKSHIRE AND THE FIRST DAY OF THE SOMME EDWARD M. -

Border Regiment in the Great War by Col. HC Wylly

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Border Regiment In The Great War by Col. H. C. Wylly Border Regiment in the Great War [Col. H. C. Wylly] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. Border Regiment in the Great War5/5(3)Publish Year: 2006Author: H. C WyllyAuthor: Col. H. C. WyllyH. C. Wylly - Wikipediahttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H._C._WyllyOverviewWorksLife• Davis, John, and H. C. Wylly (1895) The History of the Second, Queen's Royal Regiment, Now the Queen's (Royal West Surrey) Regiment: From 1715 to 1799. (R.Bentley & son).• Davis, John; Wylly, Harold Carmichael; Foster, R. C. G. (1906). The History of the Second Queen's Royal Regiment. Vol. 5. R. Bentley & Son. Col. H. C. Wylly Tightly written regimental history of the Border Regiment in the Great War, which blends the story of its 13 battalions in six theatres of war into one continuous narrative. lllustrated by 14 photographic plates and seven maps. The Border Regiment in the Great War: Author: Harold Carmichael Wylly: Publisher: Gale & Polden, 1924: Original from: the University of Michigan: Digitized: Dec 1, 2008: Length: 272 pages : Export Citation: BiBTeX EndNote RefMan border regiment in the great war Tightly written regimental history of the Border Regiment in the Great War, which blends the story of its 13 battalions in six theatres of war into one continuous narrative. Wylly, Col H. C. (1924). The Border regiment in the great war. Gale & Polden.. http://books.google.com/books?id=thPFAAAAMAAJ. Wylly, Col H. C. (1926). History of the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry Vol I, from 1755 to 1914. -

The Green Howards Regimental History

The Friends of the Green Howards Bill Cheall's Story Alexandra, Princess of Wales's Own Yorkshire Regiment (19th Foot) The North York Militia, The North York Local Militia & North York Rifle Volunteers The War of a Green Howard, 1939 - 1945. Bill Cheall's Story INTRODUCTION With the 50th Anniversary of D-Day in 1994, the Second World War will be on a lot of peoples' minds, particularly those who were a part of it. This is the true story of an ordinary soldier in the Green Howards during the Second World War. The story includes, amongst others, my experiences at Dunkirk, D-Day, a voyage on the Queen Mary and being wounded in action. It should be remembered that many of the events described in these pages have been taken from notes written soon after the events took place. The remainder has been compiled from my memoirs which I set down more than forty years ago while they were still fresh in my mind, and, more recently, I was given the inspiration to write everything down in book form so that other ex-servicemen may share some of the memories I have of that period in our lives. The 1939-45 Second World War. Bill Cheall May 1994 Before you start to read the book read A Personal Message from the Commander in Chief (this was read out to all the troops). Index 1 I AM CALLED UP 13 SICILY 2 WE JOIN THE B.E.F. 14 OUR RETURN TO ENGLAND 3 DUNKIRK 15 INTENSIVE TRAINING 4 THE AFTERMATH 16 TIME FOR ACTION 5 WE REORGANISE 17 D-5 TO D-DAY 6 TRAINING BEGINS 18 GRIM DETERMINATION 7 I AM CALLED UP 19 D+1 TO D+30 8 TO THE MIDDLE EAST 20 MY REST CURE 9 THE DESERT 21 BACK TO DUTY 10 BACK TO THE GREEN HOWARDS 22 THE EAST LANCS 11 INTO BATTLE (AT WADI AKARIT) 23 OBERHAUSEN 12 PREPARING 24 THE END OF MY WAR EPILOGUE NAMES I WILL NEVER FORGET PHOTOGRAPHS OF THE AUTHOR "Bill Cheall's War" has been provided for use on the Green Howards website by Paul Cheall, his son. -

Beaumont-Hamel and the Battle of the Somme, Onwas Them, Trained a Few and Most Were Minutes Within Killed of the Assault

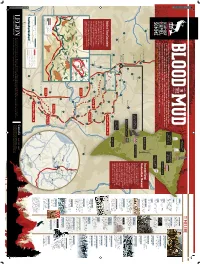

2015-12-18 2:03 PM Hunter’s CWGC TIMELINE Cemetery 1500s June 1916 English fishermen establish The regiment trains seasonal camps in Newfoundland in the rain and mud, waiting for the start of the Battle of the Somme 1610 The Newfoundland Company June 28, 1916 Hawthorn 51st (Highland) starts a proprietary colony at Cuper’s Cove near St. John’s The regiment is ordered A century ago, the Newfoundland Regiment suffered staggering losses at Beaumont-Hamel in France Ridge No. 2 Division under a mercantile charter to move to a forward CWGC Cemetery Monument granted by Queen Elizabeth I trench position, but later at the start of the Battle of the Somme on July 1, 1916. At the moment of their attack, the Newfoundlanders that day the order is postponed July 23-Aug. 7, 1916 were silhouetted on the horizon and the Germans could see them coming. Every German gun in the area 1795 Battle of Pozières Ridge was trained on them, and most were killed within a few minutes of the assault. German front line Newfoundland’s first military regiment is founded 9:15 p.m., June 30 September 1916 For more on the Newfoundland Regiment, Beaumont-Hamel and the Battle of the Somme, to 2 a.m., July 1, 1916 Canadian troops, moved from go to www.legionmagazine.com/BloodInTheMud. 1854 positions near Ypres, begin Newfoundland becomes a crown The regiment marches 12 kilo- arriving at the Somme battlefield Y Ravine CWGC colony of the British Empire metres to its designated trench, Cemetery dubbed St. John’s Road Sept. -

The Battle of the Somme

THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME FIRST PHASE BY JOHN BUCHAN THOMAS NELSON ft SONS, LTD., 35 & 36, PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON, E.C. EDINBURGH. NEW VORK. 4 PARIS. 1922 — THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME.* CHAPTER I. PRELIMINARIES. ROM Arras southward the Western battle- front leaves the coalpits and sour fields F of the Artois and enters the pleasant region of Picardy. The great crook of the upper Somme and the tributary vale of the Ancre intersect a rolling tableland, dotted with little towns and furrowed by a hundred shallop chalk streams. Nowhere does the land rise higher than 500 feet, but a trivial swell—such is the nature of the landscape jxfay carry the eye for thirty miles. There are few detached farms, for it is a country of peasant cultivators who cluster in villages. Not a hedge breaks the long roll of eomlands, and till the higher ground is reached the lines of tall poplars flanking the great Roman highroads are the chief landmarks. At the lift of country between Somme and Ancre copses patch tlje slopes, and the BATTLE OF THE SOMME. sometimes a church spire is seen above the trees winds iron) some woodland hamlet* The Somme faithfully in a broad valley between chalk bluffs, •dogged by a canal—a curious river which strains, “ like; the Oxus, through matted rushy isles,” and is sometimes a lake and sometimes an expanse of swamp, The Ancre is such a stream as may be found in Wiltshire, with good trout in, its pools. On a hot midsummer day the slopes are ablaze with yellow mustard, red poppies and blue cornflowers ; and to one coming from the lush flats of Flanders, or the “ black country ” of the Pas dc Calais, or the dreary levels of Champagne, or the strange melancholy Verdun hills, this land wears a habitable and cheerful air, as if remote from the oppression of war.