18) 16753 Private Arthur POPEJOY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorial at Contalmaison, France

Item no Report no CPC/ I b )03-ClVke *€DINBVRGH + THE CITY OF EDINBURGH COUNCIL Hearts Great War Memorial Fund - Memorial at Contalmaison, France The City of Edinburgh Council 29 April 2004 Purpose of report 1 This report provides information on the work being undertaken by the Hearts Great War Memorial Fund towards the establishment of a memorial at Contalmaison, France, and seeks approval of a financial contribution from the Council. Main report 2 The Hearts Great War Memorial Committee aims to establish and maintain a physical commemoration in Contalmaison, France, in November this year, of the participation of the Edinburgh l!jthand 16th Battalions of the Royal Scots at the Battle of the Somme. 3 Members of the Regiment had planned the memorial as far back as 1919 but, for a variety of reasons, this was not progressed and the scheme foundered because of a lack of funds. 4 There is currently no formal civic acknowledgement of the two City of Edinburgh Battalions, Hearts Great War Memorial Committee has, therefore, revived the plan to establish, within sight of the graves of those who died in the Battle of the Somme, a memorial to commemorate the sacrifice made by Sir George McCrae's Battalion and the specific role of the players and members of the Heart of Midlothian Football Club and others from Edinburgh and the su rround i ng a reas. 5 It is hoped that the memorial cairn will be erected in the town of Contalmaison, to where the 16thRoyal Scots advanced on the first day of the battle of the 1 Somme in 1916. -

1 Private Henry Charles Crane (Regimental Number 1405) Is

Private Henry Charles Crane (Regimental Number 1405) is buried in Doullens Communal Cemetery Extension Number 1 – Grave reference: I. B. 7. His occupation prior to military service recorded as that of a railroad worker and earning a monthly one-hundred dollars, Henry Charles Crane presented himself for medical examination in the Conception Bay community of Harbour Grace on April 7, 1915. It was a procedure which was to pronounce his as…Fit for Foreign Service. (continued) 1 Having by that time travelled to St. John’s, capital city of the Dominion of Newfoundland, he enlisted two days following his medical assessment, on April 9, at the Church Lads Brigade Armoury on Harvey Road where he was engaged at the daily private soldier’s rate a single dollar plus a ten-cent per diem Field Allowance. It was now to be a further ten days, the date April 19, before he was to undergo his attestation, to swear his Oath of Allegiance, the concluding official formality. At that moment Henry Charles Crane became…a soldier of the King. *A second source has him attesting on the day of his enlistment. There was now to be a lengthy waiting period of nine weeks less a day before Private Crane, Regimental Number 1405, was to embark onto His Majesty’s Transport Calgarian on June 20 in St. John’s Harbour and sail (almost*) directly to the United Kingdom. He was one of the two-hundred forty-two men of ‘F’ Company and eighty-five naval reservists to take passage on that day. (Right above: Naval reservists from Newfoundland, during the early days of the Great War, before their departure for the United Kingdom - from The War Illustrated) Where Private Crane was to spend the interim between his attestation and his departure on…overseas service…is not clear – and is not documented among his papers. -

Tour Sheets Final04-05

Great War Battlefields Study Tour Briefing Notes & Activity Sheets Students Name briefing notes one Introduction The First World War or Great War was a truly terrible conflict. Ignored for many years by schools, the advent of the National Curriculum and the GCSE system reignited interest in the period. Now, thousands of pupils across the United Kingdom study the 1914-18 era and many pupils visit the battlefield sites in Belgium and France. Redevelopment and urban spread are slowly covering up these historic sites. The Mons battlefields disappeared many years ago, very little remains on the Ypres Salient and now even the Somme sites are under the threat of redevelopment. In 25 years time it is difficult to predict how much of what you see over the next few days will remain. The consequences of the Great War are still being felt today, in particular in such trouble spots as the Middle East, Northern Ireland and Bosnia.Many commentators in 1919 believed that the so-called war to end all wars was nothing of the sort and would inevitably lead to another conflict. So it did, in 1939. You will see the impact the war had on a local and personal level. Communities such as Grimsby, Hull, Accrington, Barnsley and Bradford felt the impact of war particularly sharply as their Pals or Chums Battalions were cut to pieces in minutes during the Battle of the Somme. We will be focusing on the impact on an even smaller community, our school. We will do this not so as to glorify war or the part oldmillhillians played in it but so as to use these men’s experiences to connect with events on the Western Front. -

Amiens

Amiens < Somme < Picardie < France Amiens Amiens Metropolitan Tourist Office greets you Monday to Saturday 9.30 a.m. to 6.30 p.m. (6 p.m. October 1 to March 31) - Focus on the city Sunday 10 a.m. to 12 noon and 2 to 5 p.m. Amiens Metropolitan Tourist Office aison, L.Rousselin, Parc zoologique - Amiens Métropole, A.S. Flament, zoologique - Amiens Métropole, aison, L.Rousselin, Parc Information desk : 40, Notre-Dame square BP 11018 - F - 80010 Amiens cedex 1 Tél.: +33(0)322716050 • Fax: +33(0)322716051 www.visit-amiens.com [email protected] ACCUEIL ET INFORMATION DES OFFICES DE TOURISME ET SYNDICAT D’INITIATIVE Cette marque prouve la conformité à la norme NF X 50-730 et aux règles 5284 2010 03 22 80 50 20 Crédit photosM B. © www.tibo.org. : © SKERTZÒ. de certification NF 237. Elle garantit que l’accueil et l’information des clients, la promotion et la communication, la production et la commercialisation, la boutique, l’évaluation et l’amélioration de la qualité de service sont contrôlés régulièrement par AFNOR CERTIFICATION 11, rue Francis de Préssensé – 93571 SAINT DENIS LA PLAINE Cedex – France – www.marque-nf.com www.grandnord.fr Amiens Tours of Amiens Visits Notre-Dame cathedral and surrounding areas • The Cathedral is open all year • round ; guided visits, audio- • Amiens Notre-Dame Cathedral has been For more information about Starting in front of the Cathedral, from April to September, the Samarobriva barou- guides and access to the described in the following terms: light, the Somme department, ches will take you on a discovery ride of towers throughout the year perfection… built to harmonious proportions. -

The Earliest Evidence of Acheulian Occupation in Northwest

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The earliest evidence of Acheulian occupation in Northwest Europe and the rediscovery of the Moulin Received: 5 December 2017 Accepted: 19 August 2019 Quignon site, Somme valley, France Published: xx xx xxxx Pierre Antoine1, Marie-Hélène Moncel2, Pierre Voinchet2, Jean-Luc Locht1,3, Daniel Amselem2, David Hérisson 4, Arnaud Hurel2 & Jean-Jacques Bahain2 The dispersal of hominin groups with an Acheulian technology and associated bifacial tools into northern latitudes is central to the debate over the timing of the oldest human occupation of Europe. New evidence resulting from the rediscovery and the dating of the historic site of Moulin Quignon demonstrates that the frst Acheulian occupation north of 50°N occurred around 670–650 ka ago. The new archaeological assemblage was discovered in a sequence of fuvial sands and gravels overlying the chalk bedrock at a relative height of 40 m above the present-day maximal incision of the Somme River and dated by ESR on quartz to early MIS 16. More than 260 fint artefacts were recovered, including large fakes, cores and fve bifaces. This discovery pushes back the age of the oldest Acheulian occupation of north-western Europe by more than 100 ka and bridges the gap between the archaeological records of northern France and England. It also challenges hominin dispersal models in Europe showing that hominins using bifacial technology, such as Homo heidelbergensis, were probably able to overcome cold climate conditions as early as 670–650 ka ago and reasserts the importance of the Somme valley, where Prehistory was born at the end of the 19th century. -

RENFORCEMENTS DE CHAUSSEE SUR ROUTES DEPARTEMENTALES Annexe 1 Programme 2019

RENFORCEMENTS DE CHAUSSEE SUR ROUTES DEPARTEMENTALES Annexe 1 programme 2019 Année nature Longueur Coût Montant Trafic 2017 en Canton N° RD Classe Localisation dernier revêt. PR début PR Fin Surface m2 Nature travaux Observations ml unitaire en euros TTC V/j revêt. existant ABBEVILLE 2 / MARTAINNEVILLE / TOURS-EN-VIMEU 2001 ES 5558 dont 29 1 19+807 21+027 1 220 14 000 BBSG 22,00 310 000 Arrachement des matériaux GAMACHES Echangeur A28 2002 BB 10 % de PL 950 dont Faïençage et pelade ALBERT 11 2 MARIEUX 1997 ES 23+133 23+898 765 5 000 BBSG 24,00 120 000 7 % de PL Continuité d’itinéraire 2351 dont ALBERT 42 2 MORLANCOURT 1998 ES 5+586 6+598 1 022 7 000 BBSG 20,00 140 000 Pelade localisée et faïençage 5 % de PL 2920 dont DOULLENS 925 1 FIENVILLERS 1993 ES 56+004 57+048 1 077 7 800 EME + BBSG 55,00 450 000 11 % de PL Usure du revêtement Pelade Départ de matériaux BERNAVILLE (Partie Sud) 2920 dont DOULLENS 925 1 2002 BB 51+722 52+611 898 6 500 BBSG 24,00 185 000 De la RD 99 / Direction FIENVILLERS 11 % de PL DOULLENS / 10 GB+BBSG 1316 dont 216 2 BERNEUIL / DOMART-EN-PONTHIEU 2008 ES 4+865 8+313 3 453 25 000 60,00 1 600 000 FLIXECOURT Poutres 13 % de PL Ornièrage significatif en rives Défaut d’adhérence généralisé Fissures longitudinales Carrefour RD 12 / RD 216 à la sortie Reconstruction de 1316 dont FLIXECOURT 216 2 d’agglomération de DOMART-EN- 2008 ECF 8+313 8+738 425 2 550 110,00 290 000 chaussée 13 % de PL PONTHIEU Reconstruction 1995 BB 3560 dont Ornièrage HAM 1017 1 MARCHELEPOT 25+694 26+928 1 238 9 600 partielle et 60,00 580 000 1997 -

The Western Front;

The Western Front Drawings by Muirhead Bone PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF THE WAR OFFICE FROM THE OFFICES OF "COUNTRY LIFE" LTD 20 TAVISTOCK STREET COVENT GARDEN LONDON MCMXVII GENERAL SIR DOUGLAS HAIG, GCB, GCVO, KCIE. GRAND PLACE AND RUINS OF THE CLOTH HALL, YPRES The gaunt emptiness of Ypres is expressed in this drawing, done from the doorway of a ruined church in a neighbouring square. The grass has grown long this summer on the Grand Place and is creeping up over the heaps of ruins. The only continuous sound in Ypres is that of birds, which sing in it as if it were country. A STREET IN YPRES In the distance is seen what remains of the Cloth Hall. On the right a wall long left unsupported is bending to its fall. The crash of such a fail is one of the few sounds that now break the silence of Ypres, where the visitor starts at the noise of a distant footfall in the grass-grown streets. DISTANT VIEW OF YPRES The Ypres salient is here seen from a knoll some six miles south-west of the city, which is marked, near the centre of the drawing, by the dominant ruin of the cathedral. The German front line is on the heights beyond, Hooge being a little to the spectator’s right of the city and Zillebeke slightly more to the right again. Dickebusch lies about half way between the eye and Ypres. The fields in sight are covered with crops, varied by good woodland. To a visitor coming from the Somme battlefield the landscape looks rich and almost peaceful. -

Memorials to Scots Who Fought on the Western Front in World War One

Memorials to Scots who fought on the Western Front in World War One Across Flanders and France there are many memorials to those of all nations Finding the memorials who fell in World War One. This map is intended to assist in identifying those for The map on the next page shows the general location on the the Scots who made the ultimate sacrifice during the conflict. Western Front of the memorials for Scottish regiments or Before we move to France and Flanders, let’s take a look at Scotland’s National battalions. If the memorial is in a Commonwealth War Graves War Memorial. Built following World War One, the memorial stands at the Commission Cemetery then that website will give you directions. highest point in Edinburgh Castle. Designed by Sir Robert Lorimer and funded by donations, the memorial is an iconic building. Inside are recorded the names of all Scots who fell in World War One and all subsequent For other memorials and for road maps you could use an conflicts while serving in the armed forces of the United online map such as ViaMichelin. Kingdom and the Empire, in the Merchant Navy, women’s and nursing services, as well as civilians killed at home and overseas. What the memorials commemorate The descriptions of the memorials in this list are designed to give you a brief outline of what and who is being commemorated. By using the QR code provided you will be taken to a website that will tell you a bit more. Don’t forget there are likely to be many more websites in various formats that will provide similar information and by doing a simple search you may find one that is more suitable for your interest. -

The Marshlands of Méricourt-Sur-Somme

Boisement Water Chipilly Belvedere (viewpoint) Prairie-Pâture Agricultural land Larris Wooded areas Espace urbanisé Wetlands at the bottom of the valley Somme Canal Reed Beds Lock-keeper’s House Départ Eglise de Le-Quesne Wooden foot-bridge me Un des points de vue les m plus hauts de la Somme o Starting Point S D Lock-keeper’s house at d l Méricourt-sur-Somme O Préservons la nature Vous participez à la conservation de la richesse P Car Park de ce site fragile : . en empruntant les sentiers, . en refermant les passe-clôtures après votre passage, ! Be careful: . en respectant sa faune et sa flore, Hunting is carried out on . en emportant vos déchets en quittant le site. this site during the official P Rannou © S. hunting period. Please be careful during this period. Starting at: Car park at Protect the natural The Marshlands of the lock-keeper’s house at Méricourt-sur-Somme Méricour environment D To help with the conservation of the rich natural habitats of this fragile Méricourt-sur-Somme t-sur site, please: Time: 30 mins Méricourt-sur-Somme, By visiting the marshlands of -Somme . Always use the marked trails . Keep gates and stiles closed 8km from Bray-sur-Somme, Méricourt, nature will reveal all of its . Respect the fauna and flora 31km from Amiens beauty. Hiking, hunting, fishing, and nature Distance: 1,5km . Take your litter away with you discovery activities - something N 0 50 100m for everyone. This trail is maintained by Route: easy the Poppy Country Sign posts Route continues Wrong direction Change of direction For more information: -

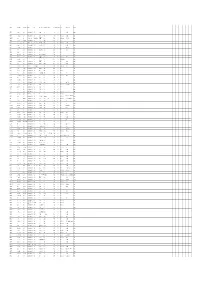

738 Albert – Bray/Somme – Peronne Horaires Valables Du 2 Sept

738 ALBERT – BRAY/SOMME – PERONNE HORAIRES VALABLES DU 2 SEPT. 2021 AU 6 JUIL. 2022 PERIODE SCOLAIRE PETITES VACANCES Jours de circulation > LMmJVS mS mS LMmJVS LMmJVS mS mS LMmJVS 38131 38531 38616 38600 38176 38576 38616 38600 ALBERT Gare SNCF Café du Départ 1 06:45 13:40 18:15 19:20 1 06:45 13:15 18:15 19:20 1 MEAULTE Aérospatiale 2 06:50 13:45 18:22 19:27 2 06:50 13:20 18:22 19:27 2 BRAY SUR SOMME Eglise 3 06:57 13:52 18:31 19:36 3 06:57 13:27 18:31 19:36 3 CAPPY Ecluse 4 07:01 13:56 18:36 19:41 4 07:01 13:31 18:36 19:41 4 CHUIGNES Rue de Cappy 5 07:05 14:00 (2) (2) 5 07:05 13:35 (2) (2) 5 DOMPIERRE BECQUINCOURT Sucrerie 6 07:08 14:03 (2) (2) 6 07:08 13:38 (2) (2) 6 DOMPIERRE BECQUINCOURT Place Thellier 7 07:09 14:04 18:41 19:46 7 07:09 13:39 18:41 19:46 7 DOMPIERRE BECQUINCOURT Becquincourt 8 07:10 14:05 18:42 19:47 8 07:10 13:40 18:42 19:47 8 FRISE Le Four Banal 9 07:16 14:11 (2) (2) 9 07:16 13:46 (2) (2) 9 HERBECOURT Place publique 10 07:22 14:17 18:45 19:50 10 07:22 13:52 18:45 19:50 10 FLAUCOURT Carrefour RD1 11 07:25 14:20 18:46 19:51 11 07:25 13:55 18:46 19:51 11 BIACHES Rue de Péronne 12 07:30 14:25 18:49 19:54 12 07:30 14:00 18:49 19:54 12 PERONNE Rue de l'Industrie (La Chapelette) 13 07:32 14:27 18:52 19:57 13 07:32 14:02 18:52 19:57 13 PERONNE Sacré Coeur 14 07:37 I I I 14 IIII 14 PERONNE Rue Saint Sauveur 15 07:40 14:30 18:55 20:00 15 07:35 14:05 18:55 20:00 15 PERONNE Cité Scolaire 16 07:45 16 16 Jours de circulation : L " Lundi ; M " Mardi ; m " Mercredi ; J " Jeudi ; V " Vendredi ; S " Samedi Attention : Les cars ne circulent pas les jours fériés (lundi de Pentecôte compris). -

Article Aims at Answering the Following Derstand the 2001 flooding (Hubert, 2001; Pointet Et Al., Questions: 2003; Negrel´ and Petelet-Giraud´ , 2005)

Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 14, 99–117, 2010 www.hydrol-earth-syst-sci.net/14/99/2010/ Hydrology and © Author(s) 2010. This work is distributed under Earth System the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Sciences Multi-model comparison of a major flood in the groundwater-fed basin of the Somme River (France) F. Habets1,2, S. Gascoin2, S. Korkmaz3, D. Thiery´ 4, M. Zribi5, N. Amraoui4, M. Carli2, A. Ducharne2, E. Leblois6, E. Ledoux3, E. Martin1, J. Noilhan1, C. Ottle´5,7, and P. Viennot3 1GAME/CNRM (Met´ eo-France/CNRS),´ URA 1357, Toulouse, France 2UMR-Sisyphe, UMR 7619, Sisyphe, CNRS UPMC, Paris, France 3Centre de Geosciences/Mines-Paristech,´ Fontainebleau, France 4BRGM, Orleans,´ France 5CETP, Velizy,´ France 6CEMAGREF, Lyon, France 7LSCE, Gif-sur-Yvette, France Received: 4 September 2009 – Published in Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss.: 28 September 2009 Revised: 24 December 2009 – Accepted: 6 January 2010 – Published: 18 January 2010 Abstract. The Somme River Basin is located above a chalk the flooding of 2001 was characterized by an increase in the aquifer and the discharge of the somme River is highly in- quantity of the overflow and not much by a spreading of fluenced by groundwater inflow (90% of river discharge is the overflow areas. Inconsistencies between river discharge baseflow). In 2001, the Somme River Basin suffered from a and piezometric levels suggest that further investigation are major flood causing damages estimated to 100 million euro needed to estimate the relative influence of unsaturated and (Deneux and Martin, 2001). The purpose of the present re- saturated zones on the hydrodynamics of the Somme River search is to evaluate the ability of four hydrologic models Basin. -

Wfdwa-Rsl-181112

SURNAME FIRST NAMES RANK at Death REGIMENT UNIT WHERE BORN BORN STATE HONOURS DOD (DD MMM) YOD (YYYY) COD PLACE OF DEATH COUNTRY A'HEARN Edward John Private Australian Infantry, AIF 44th Bn Wilcannia NSW 4 Oct 1917 KIA In the field Belgium AARONS John Fullarton Private Australian Infantry, AIF 16th Bn Hillston NSW 11 Jul 1917 DOW (Wounds) In the field France Manchester, ABBERTON Edmund Sapper Australian Engineers 3rd Div Signal Coy England 6 Nov 1918 DOI (Illness, acute) 1 AAH, Harefield England Lancashire ABBOTT Charles Edgar Lance Corporal Australian Infantry, AIF 11th Bn Avoca Victoria 30 May 1916 KIA - France ABBOTT Charles Henry Sapper Australian Engineers 3rd Tunnelling Coy Maryborough Victoria 26 May 1917 DOW (Wounds) In the field France ABBOTT Henry Edgar Private Australian Army Medical Corp10th AFA Burra or Hoylton SA 12 Oct 1917 KIA In the field Belgium ABBOTT Oliver Oswald Private Australian Infantry, AIF 11th Bn Hoyleton SA 22 Aug 1916 KIA Mouquet Farm France ABBOTT Robert Private Australian Infantry, AIF 11th Bn Malton, Yorkshire England 25 Jul 1916 KIA France France ABOLIN Martin Private Australian Infantry, AIF 44th Bn Riga Russia 10 Jun 1917 KIA - Belgium ABRAHAM William Strong Private Australian Infantry, AIF 11th Bn Mepunga, WarnnamboVictoria 25 Jul 1916 KIA - France Southport, ABRAM Richard Private Australian Infantry, AIF 28th Bn England 29 Jul 1916 Declared KIA Pozieres France Lancashire ACKLAND George Henry Private Royal Warwickshireshire Reg14th Bn N/A N/A 8 Feb 1919 DOI (Illness, acute) - England Manchester, ACKROYD