Wodehouse and the First World War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Little Nugget

WODEHOUSE THE LITTLE NUGGET NY PUBLIC LIBRARY THE BRANCH LIBRARIES 3 3333 11794 7081 I 1 Lr W Wodehouse, P. G. The 1 ittle nugget / 874858 TheNe Public Aator, Lenox and 1 Penguin Books The Little Nugget P. G. Wodehouse was born in Guildford in 1881 and educated at Dulwich College. After working for the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank for two years, he left to earn his living as a journalist and storywriter, writing the 'By the Way* column in the old Globe. He also contributed a series of school stories to a magazine for boys, the Captain, in one of which Psmith made his first appearance. Going to America before the First World War, he sold a serial to the Saturday Evening Post and for the next twenty-five years almost all his books appeared first in this magazine. He was part author and writer of the lyrics of eighteen musical comedies including Kissing Time; he married in 1914 and in 1955 took American citizenship. He wrote over ninety books and his work has won world-wide acclaim, being translated into many languages. The Times hailed him as 'a comic genius recognized in his lifetime as a classic and an old master of farce'. P. G. Wodehouse said, *I believe there are two ways of writing novels. One is mine, making a sort of musical comedy without music and ignoring real life altogether; the other is going right deep down into life and not caring a damn . .' He was created a Knight of the British Empire in the New Year's Honours List in 1975. -

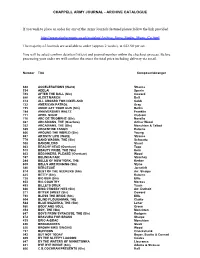

Chappell Army Journals

CHAPPELL ARMY JOURNAL - ARCHIVE CATALOGUE If you wish to place an order for any of the Army Journals featured please follow the link provided. http://www.studio-music.co.uk/acatalog/Archive_Items_Studio_Music_Co.html The majority of Journals are available to order (approx 2 weeks), at £42.50 per set. You will be asked confirm details of title(s) and journal number within the checkout process. Before processing your order we will confirm the exact the total price including delivery via email. Number Title Composer/Arranger 688 ACCELERATIONS (Waltz) Strauss 534 ADELAI Spurin 783 AFTER THE BALL (SIn) Coward 686 ALERT MARCH Bell 414 ALL ABOARD FOR DIXIELAND Cobb 722 AMERICAN PATROL Gray 735 ANNIE GET YOUR GUN (SIn) Berlin 744 ANNIVERSARY WALTZ Franklin 711 APRIL NIGHT Clutsam 710 ARC DE TRIOMPHE (SIn) Novello 467 ARCADIANS, THE (Overture) Arthur Wood 352 ARCADIANS, THE (SIn) Monckton & Talbot 389 ARGENTINE TANGO Rubens 806 AROUND THE WORLD (SIn) Young 697 ARTISTS' LIFE (Waltz) Strauss 779 BAND WAGON, THE (SIn) Schwartz 308 BANDOLERO Stuart 663 BEACHY HEAD (Overture) Tapp 513 BEAUTY PRIZE, THE (SIn) Kern 603 BEGINNERS, PLEASE! (Overture) Wood 747 BELINDA FAIR Strachey 244 BELLE OF NEW YORK, THE Kerker 809 BELLS ARE RINGING (SIn) Styne 540 BERCEUSE Jarnefelt 874 BEST OF THE SEEKERS (SIn) Arr. Sharpe 425 BETTY (SIn) Rubens 728 BIG BEN (SIn) Ellis 853 BIG COUNTRY Moross 493 BILLETS DOUX Yuain 666 BING CROSBY HITS (SIn) Arr. Duthoit 571 BITTER SWEET (SIn) Coward 733 BLESS THE BRIDE (SIn) Ellis 504 BLIND PLOUGHMAN, THE Clarke 544 BLUE MAZURKA, -

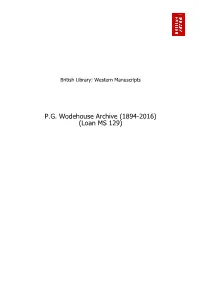

PG Wodehouse Archive

British Library: Western Manuscripts P.G. Wodehouse Archive (1894-2016) (Loan MS 129) Table of Contents P.G. Wodehouse Archive (1894–2016) Key Details........................................................................................................................................ 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................................... 1 Provenance........................................................................................................................................ 2 Related Resources.............................................................................................................................. 2 Loan MS 129/1 P.G. Wodehouse Archive: Manuscript Material (1900–2004)........................................... 2 Loan MS 129/2 P.G. Wodehouse Archive: Wartime Material (1939–2015)............................................... 86 Loan MS 129/3 P.G. Wodehouse Archive: Theatrical and Cinematic Work (1905–2008)........................... 97 Loan MS 129/4 P.G. Wodehouse Archive: Correspondence (1899–2010)................................................ 111 Loan MS 129/5 P.G. Wodehouse Archive: Published Material (1899–2003)............................................. 187 Loan MS 129/6 P.G. Wodehouse Archive: Biographical Material (1894–2001)......................................... 210 Loan MS 129/7 P.G. Wodehouse Archive: Posthumous Material (1929–2016)......................................... 218 Loan MS 129/8 P.G. Wodehouse -

Guide to the Donald J. Stubblebine Collection of Theater and Motion Picture Music and Ephemera

Guide to the Donald J. Stubblebine Collection of Theater and Motion Picture Music and Ephemera NMAH.AC.1211 Franklin A. Robinson, Jr. 2019 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Stage Musicals and Vaudeville, 1866-2007, undated............................... 4 Series 2: Motion Pictures, 1912-2007, undated................................................... 327 Series 3: Television, 1933-2003, undated............................................................ 783 Series 4: Big Bands and Radio, 1925-1998, -

Appendix 1 Number of Individuals out of Every 1000 Who Could Not Sign Their Name on a Marriage Register: 1896–1907

Appendix 1 Number of individuals out of every 1000 who could not sign their name on a marriage register: 1896–1907 Male Female Total 1896–1900 32 37 69 1901–1905 20 24 44 1905–1907 27 27 54 236 Appendix 2 Extract from Beatrice Harraden, ‘What Our Soldiers Read’, Cornhill Magazine, vol. XLI (Nov. 1916) Turning aside from technical subjects to literature in general, I would like to say that although we have not ever attempted to force good books on our soldiers, we have of course taken great care to place them within their reach. And it is not an illusion to say that when the men once begin on a better class of book, they do not as a rule return to the old stuff which formerly constituted their whole range of reading. My own impression is that they read rubbish because they have had no one to tell them what to read. Stevenson, for instance, has lifted many a young soldier in our hospital on to a higher plane of reading whence he has looked down with something like scorn – which is really very funny – on his former favourites. For that group of readers, ‘Treasure Island’ has been a discovery in more senses than one, and to the librarians a boon unspeakable. We have had, however, a large number of men who in any case care for good literature, and indeed would read nothing else. Needless to say, we have had special pleasure in trying to find them some book which they would be sure to like and which was already in our collection, or else in buying it, and thus adding to our stock. -

The Cambridge Companion to the Musical Edited by William A

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-11474-6 — The Cambridge Companion to the Musical Edited by William A. Everett , Paul R. Laird Index More Information Index ABBA, 291, 293, 361 Allen, Peter, 361 Abbott, Emma, 41–42, 50 Allyson, June, 148 Abbott, George, 136, 155, 198, 208, 212, 217, Alt Heidelberg (play), 104 237–39, 265–68, 270, 273, 276, 279, 372 Altar Boyz, 377 ABC Stage 67, 426 Altman, Robert, 162 Abyssinia, 124, 127 Amberg, Gustav, 70 Ace of Clubs, 162, 174 Ambler, Scott, 370 Acheson, Dean, 176 Amen Corner, 362 Acito, Marc, 364 ‘America’, 240, 261, 380 Act, The, 273 ‘American Dream, The’, 303 Adam, Adolphe, 34 American Idiot, 296, 300, 361 Adamini, Arturo, 71 American Idol, 320, 410, 424, 431–32 Adams, Lee, 220, 282 American in Paris, An (film), 371, 387, 392 ‘Adelaide’, 413 American in Paris, An (show), 340, 352, 371 Adamson, Samuel, 335 American Psycho, 329, 335 Adler, Jacob P., 66 Amerikaner Shadkhn,75 Adler, Richard, 217 Amos, Tori, 335 Adolf Philipp Theatre, 65 Amour, 350 Adolf Philipp, Adoph, 65–69, 77, 445 ‘American Women’, 271 Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, ‘Amores chicanos’,74 The, 372 Anderson, Carl, 309 Africaine, L’, 118 Anderson, Maxwell, 132, 136–37, 232, 236–37, After the Ball (show), 129, 162, 165 242–43 ‘After the Ball’, 129 Andersson, Benny, 291 Agee, James, 239 Andrews Sisters, 238 ‘Agony’, 254 Andrews, Julie, 1, 199, 215, 223, 320, 412–13, Aguglia, 72 418, 425 ‘Ah! Sweet Mystery of Life’,91 Androcles and the Lion, 201 Aida (show), 293, 320, 359, 376 ‘Angel of Music’, 315 Aimée, Marie, 43 ‘Ankunft -

Wodehouse and the Comic Concussion

The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 30 Number 2 Summer 2009 See pages 16–19 for some last-minute convention news. We hope to see you in St. Paul on June 12–14! Wodehouse and the Comic Concussion by David Landman Who would these swings and parries take When he might a quietus make With a bare knuckle? —Willie “The Shaker” Shakespeare nce, when reconnecting a loose wire under the dash Oof my Hudson Hornet, I stretched out on my back the length of the front seat. Made aware that the open door was blocking traffic, I reached back to the armrest and, forgetting that it extended a good three inches beyond the plane of the door, slammed it shut. When I regained consciousness my first thought was that Stumpf, who spoke of the “falscher Schmuck und nutzloser Plunder” of feudalism, was talking through his Kaiser Bill pickelhaube. After that, I thought no more for a week as I wandered aimlessly along Slaphappy Street. A concussion is not a funny thing. Except in Wodehouse. Setting aside the sagas of professional bruisers like Kid Brady, I speak here only of the collateral havoc wreaked upon itself by the civilian population. It is remarkable how many of them are flattened and how readily they bounce up off the canvas, not much the worse for wear, in that martial arts academy known as the English country house. I do not complain. It is mostly the deserving who get their comeuppance. I remark only how smoothly the scorched-earth policy goes David Landman, fully recovered (we think) from his down thanks to the effervescence of the Wodehouse touch. -

Wodehouse on the Arno

The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 31 Number 3 Autumn 2010 Wodehouse on the Arno by Bob (Oily Carlisle) Rains n The Luck of the Bodkins, the Master speaks of “the shifty, hangdog look which Iannounces that an Englishman is about to talk French.” Fortunately for Plum, he was never subjected to the modern-day Carlisles (Sweetie & me) mangling l’Italiano while we stroll from gelateria to gelateria in la bella Firenze, the capital of Toscana. Likewise lucky is Dante, the father of modern Italian. It is well known that in World War II the U.S. Marines fooled our Asian foe by using Navajos to translate our coded messages into their native tongue. Those impenetrable Navajo code talkers had nothing on Sweetie and me. Not only can no American understand our Carlislian version of Italian, but—as repeatedly demonstrated in various negozi (shops)—neither can the most clever Italian. Oily and Sweetie Carlisle (Bob Since the four-week summer course I teach in Florence, whenever I wangle it, Rains and Andrea Jacobsen) at meets at most two hours a day, I can find myself with time on my hands and only so the 2009 St. Paul convention, much pizza and pasta that I can mange (eat) without serious physical consequences. prior to their “career” as Knowing this, I had brought along on our Florence junket this year my well- il traduttori di Plum thumbed Vintage Wodehouse (edited by Richard Usborne) to help me while away the moments between meals. Then, to add panna (whipped cream) to gelato (no translation necessary, I trust), one day at the Libreria Martinelli on via Cavour, I found a whole shelf of Wodehouse in Italiano! I was molto contento! Naturally, I bought Il Meglio di P. -

The Cambridge Companion to the Musical Edited by William A

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-68084-4 — The Cambridge Companion to the Musical Edited by William A. Everett , Paul R. Laird Index More Information Index Shows, sources of shows, songs, and dances are listed by title, not under author’s names. Titles in italics with no parenthetical identification are staged musicals or operas. Song titles are in single quotation marks. ‘A Woman’s Touch’, 122 Allegro,156–7,160,169,189,223,337 ABBA, 244, 246, 289 Allen, Frederick Lewis, 103 Abbott, Emma, 22 Allen, Peter, 288 Abbott, George, 107, 160, 169, 173, 178, 197–8, Allyson, June, 118 221–4, 226, 229, 232 Alt Heidelberg (play), 77 Abyssinia, 96, 99 Altar Boyz,299 Ace of Clubs,129,139 Altman, Robert, 129 Acheson, Dean, 141 Amberg, Gustav, 45 Act, The,229 Ambros, Wolfgang, 277 Adam, Adolphe, 15 Amen Corner,289 Adamini, Arturo, 48 ‘America’, 200, 218 Adams, Lee, 181–2, 236 ‘American Dream, The’, 251–2 ‘Adelaide’, 332 American in Paris, An (film), 309, 314 Adenberg, Wolfgang, 277 ‘American Women’, 226–8 Adler, Jacob P., 43 Amerikaner Shadkhn,51 Adler, Richard, 173, 178 America’s Sweetheart,106 Adventures of Harlequin and Scaramouche, ‘Amores chicanos’, 50 The,4 Amour,281 Adventures of Priscilla, The (film), 295 Anderson, Carl, 257 Adventures of Priscilla, The (show), 295 Anderson, Maxwell, 103, 107–8, 192–3, 196–7 Africaine, L’,90 Andersson, Benny, 244 After the Ball (show), 129, 132 Andrews, Julie, 160, 176, 183, 268, 331, 336 ‘After the Ball’, 100 Androcles and the Lion,162 Agee, James, 199 ‘Angel of Music’, 263–4 ‘Agony’, 212 ‘Ankunft der Grunhorner,¨ -

MUSICAL THEATRE a History

MUSICAL THEATRE A History John Kenrick This book is dedicated to Mary Pinizzotto Kenrick Marotta and Frank Crosio. Neither my life nor this book would be possible without their unfailing support. CONTENTS Acknowledgments 9 Introduction “Let’s Start at the Very Beginning . .” 11 1 Ancient Times to 1850—“Playgoers, I Bid You Welcome!” 18 2 Continental Operetta (1840–1900)— “Typical of France” 35 3 American Explorations (1624–1880)— “The Music of Something Beginning” 50 4 Gilbert and Sullivan (1880–1900)— “Object All Sublime” 75 5 The Birth of Musical Comedy (1880–1899)— “It Belong’d to My Father Before I Was Born” 95 6 A New Century (1900–1913)—“Whisper of How I’m Yearning” 111 7 American Ascendance (1914–1919)—“In a Class Beyond Compare” 134 8 Al Jolson—“The World’s Greatest Entertainer” 156 9 The Jazz Age (1920–1929)—“I Want to Be Happy” 168 10 Depression Era Miracles (1930–1940)— “Trouble’s Just a Bubble” 207 11 A New Beginning (1940–1950)—“They Couldn’t Pick a Better Time” 238 8 CONTENTS 12 Broadway Takes Stage (1950–1963)— “The Street Where You Live” 265 13 Rock Rolls In (1960–1970)—“Soon It’s Gonna Rain” 298 14 New Directions (1970–1979)—“Vary My Days” 318 15 Spectacles and Boardrooms—“As If We Never Said Goodbye” 342 16 Musical Comedy Returns (The 2000s)— “Where Did We Go Right?” 370 Suggested Reading: An Annotated Bibliography 383 Recommended Web Resources 394 Index 395 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It would be impossible for me to thank all the people who have inspired, assisted, and cajoled me in the process of creating this book, but a few curtain calls are in order. -

By the Way March 11.Qxd

Number 43 March 2011 The Ladies of the Grossmith Company Notes written by Eddie Grabham about five of the most important female actors who appeared in musical comedies from 1919 at the Winter Garden Theatre, London, under George Grossmith Jr’s management. Yvonne Arnaud (1895–1958) Phyllis Dare (1890–1975) French-born Yvonne Arnaud became a popular Edwardian beauty Phyllis Dare graced the London actress in England. She shone in light and musical stage for half a century following her debut in comedy following her success in The Girl in the Taxi pantomime with older sister Zena in 1899. Seymour (Lyric Theatre, 1912). Hicks cast her as Mab in Bluebell in Fairyland at the She played Georgette St Pol in Kissing Time (1919), Vaudeville (1901). She played Eileen Cavanagh in the English version of Wodehouse, Bolton and Robert Courtneidge’s production of The Arcadians composer Ivan Caryll’s The Girl Behind the Gun , (1909) for over a year until her role was taken over which ran for 160 performances on Broadway. by Courtneidge’s daughter Cicely. Wodehouse and Bolton’s book was based on Madam When George Edwardes was looking for a and her Godson by Maurice Hennequin and Pierre replacement for his great star Gertie Millar at the Weber, and was the only show Plum wrote which Gaiety, he gave Phyllis Dare the title role in Peggy reflected the First World War. The London version (1911). She then played Prudence in the Paris nearly trebled the length of the Broadway run with production of The Quaker Girl before Edwardes 430 performances at the new Winter Garden. -

Musical Comedies with Lyrics Written By

The P G Wodehouse Society (UK) Information Sheet Number 5 Revised December 2018 Musical Comedies with Lyrics Written by P G Wodehouse The difficulties which arise in trying to prepare a comprehensive list of productions to which Wodehouse contributed lyrics come mainly in deciding whether to include shows in which a lyric appeared almost by chance, ie a lyric which had not been written for that show. His best-known song, Bill, falls into that category, its second appearance (in Showboat) being far more memorable than its first, in the pre-Broadway try-out of Oh, Lady! Lady!!. On the other hand, the mere appearance of one of his lyrics in a post-war production not having any specific connection with an accepted Wodehouse-related show barely warrants inclusion. This list is essentially restricted to shows in which new, or substantially revised, Wodehouse lyrics appear for the first time. Because of the relevance of the original production of Very Good, Eddie to Wodehouse’s first involvement with American musical theatre, its successful 1970s revival, which included two Wodehouse interpolations, has also been included. P G Wodehouse personally preferred the term ‘lyrist’ to the more common ‘lyricist’. SHOWS TO WHICH PGW CONTRIBUTED VIRTUALLY ALL THE LYRICS Year Title Composer(s) 1917 Have a Heart Jerome Kern 1917 Oh, Boy! Jerome Kern 1917 Leave It To Jane Jerome Kern 1917 Miss 1917 Jerome Kern 1918 Oh, Lady! Lady!! Jerome Kern 1918 See You Later Jean Schwartz & William F Peters 1918 The Girl Behind the Gun Ivan Caryll 1918 Oh, My Dear! Louis