MUSICAL THEATRE a History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fences Study Guide

Pacific Conservatory Theatre Student Matinee Program Presents August Wilson’s Fences Generously sponsored by Franca Bongi-Lockard Nancy K. Johnson A Study Guide for Educators Welcome to the Pacific Conservatory Theatre A NOTE TO THE TEACHER Thank you for bringing your students to PCPA at Allan Hancock College. Here are some helpful hints for your visit to the Marian Theatre. The top priority of our staff is to provide an enjoyable day of live theatre for you and your students. We offer you this study guide as a tool to prepare your students prior to the performance. SUGGESTIONS FOR STUDENT ETIQUETTE Note-able behavior is a vital part of theater for youth. Going to the theater is not a casual event. It is a special occasion. If students are prepared properly, it will be a memorable, educational experience they will remember for years. 1. Have students enter the theater in a single file. Chaperones should be one adult for every ten students. Our ushers will assist you with locating your seats. Please wait until the usher has seated your party before any rearranging of seats to avoid injury and confusion. While seated, teachers should space themselves so they are visible, between every groups of ten students. Teachers and adults must remain with their group during the entire performance. 2. Once seated in the theater, students may go to the bathroom in small groups and with the teacher's permission. Please chaperone younger students. Once the show is over, please remain seated until the House Manager dismisses your school. 3. Please remind your students that we do not permit: - food, gum, drinks, smoking, hats, backpacks or large purses - disruptive talking. -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

Spirit of Ame Rica Chee Rle a D E Rs

*schedule subject to change SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY MORNING MORNING MORNING MORNING MORNING MORNING MORNING Arrive at New York Hilton 7 am 8 am 6 am 8 am 5:30 am Shuttle Service Midtown for Event Check-in Coupon Breakfast Coupon Breakfast TODAY Show Coupon Breakfast Uniform Check Assemble/Depart Final Run Through Rhinelander 10 am–5 pm 8–11 am 9 am 8:30 am 9 am Grand Ballroom Gallery Luggage Drop-off Rehearsal Spectators and Performers Check out with Dress Rehearsal Rhinelander Gallery America’s Hall I Assemble/Check-out Spectator America’s Hall I 6 am America’s Hall I America’s Hall I Depart Hilton for Parade Event Check-in Spectators Return to hotel by 10:30 am America’s Hall I 8 am • Statue of Liberty Room Check. Move to Grand Ballroom 9 am–12 pm Assemble in • Harbor Cruise 92nd Macy’s Thanksgiving • Orientation Rhinelander Gallery for • 9/11 Memorial 9 am Spectators Day Parade!® • Packet Pick-up Big Apple Tour • One World Observatory Coupon Breakfast 10:30 am • Hotel Check-in Tour ends in Times Square View from 4th Floor Balcony 10 am–12 pm at 11 am 12:30 pm • Times Square Check out with • Central Park Spectator Return to hotel by Room Check. AFTERNOON AFTERNOON AFTERNOON AFTERNOON AFTERNOON AFTERNOON 10 am–5 pm 11:30 am Coupon Lunch 12 pm 1 pm 12 pm • If rooms are not available, Coupon Lunch Coupon Lunch Coupon Lunch Coupon Lunch Continue Activities Have a you may wait in safe America’s Hall II 1 pm 2 pm 2-6 pm TBD Aladdin journey Radio City Music Hall Macy’s / Empire State Building Check out with • Report to our New Amsterdam Theatre Christmas Spectacular Spectator home! Information Desk 214 W. -

Program Notes

“Come on along, you can’t go wrong Kicking the clouds away!” Broadway was booming in the 1920s with the energy of youth and new ideas roaring across the nation. In New York City, immigrants such as George Gershwin were infusing American music with their own indigenous traditions. The melting pot was cooking up a completely new sound and jazz was a key ingredient. At the time, radio and the phonograph weren’t widely available; sheet music and live performances remained the popular ways to enjoy the latest hits. In fact, New York City’s Tin Pan Alley was overflowing with "song pluggers" like George Gershwin who demonstrated new tunes to promote the sale of sheet music. George and his brother Ira Gershwin composed music and lyrics for the 1927 Broadway musical Funny Face. It was the second musical they had written as a vehicle for Fred and Adele Astaire. As such, Funny Face enabled the tap-dancing duo to feature new and well-loved routines. During a number entitled “High Hat,” Fred sported evening clothes and a top hat while tapping in front of an enormous male chorus. The image of Fred during that song became iconic and versions of the routine appeared in later years. The unforgettable score featured such gems as “’S Wonderful,” “My One And Only,” “He Loves and She Loves,” and “The Babbitt and the Bromide.” The plot concerned a girl named Frankie (Adele Astaire), who persuaded her boyfriend Peter (Allen Kearns) to help retrieve her stolen diary from Jimmie Reeve (Fred Astaire). However, Peter pilfered a piece of jewelry and a wild chase ensued. -

Meeting Planner's Guide 2019

AN ADVERTISING SUPPLEMENT TO CRAin’S NEW YORK BUSINESS MEETING Planner’S GUIDE 2019 YOUR RESOURCE FOR SUCCESSFUL MEETINGS AND EVENTS IF YOU ARE A MEETING or event hotels in the New York City area. than other channels. A lot of that a trend toward “bleisure,” the walk the line between creating planner you are part of an elite, Our goal is to keep you ahead value comes from networking in combining of business travel and experiences that resonate with multi-talented group. Being a of the curve and one up on the person. One-on-one meetings leisure. Today’s event attendees the whole audience, as well as planner calls for a wide range of competition in 2019. have become a hot commodity; expect event planners to be equal with individual attendees. expert skills and qualifications, To that end, here are some research has shown that, after parts manager and travel agent. such as managing, budgeting and of the meeting and event trends content, networking is the sec- Everything from programming to GIVE THEM execution, knowledge of tech- to consider when planning ond biggest motivator for event catering is likely to reference the A SHOW nology, creative talent—not to this year: attendees today. And the term locality and culture of the desti- 2019 also sees a trend for the mention leadership, adaptability, “networking” covers everything nation both on-site and off. “festivalization” of meetings and people skills, patience and energy IN YOUR FACE from spontaneous conversations events. A growing number of (to name just a few). When you “Face time” is the buzzword to huddle rooms and meet-and- TAKE IT PERSONAlly gatherings are adding perfor- possess all of these qualities you in meetings and events for greets. -

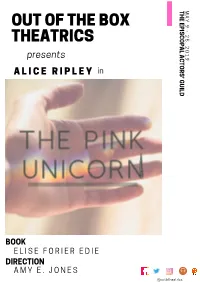

Pink Unicorn Program

M T H A E Y E OUT OF THE BOX 9 P I - S 2 C 5 THEATRICS O , P 2 A 0 L 1 A presents 9 C T O R A L I C E R I P L E Y in S ' G U I L D MUSIC & LYRICS BY STEPHEN SONDHEIM BOOK BY JAMES LAPINE BOOK E L I S E F O R I E R E D I E DIRECTION A M Y E . J O N E S @ootbtheatrics Opening Night: May 15, 2019 The Episcopal Actors' Guild 1 East 29th Street Elizabeth Flemming Ethan Paulini Producing Artistic Director Associate Artistic Director present Alice Ripley* in Out of the Box Theatrics' production of By Elise Forier Edie Technical Design Dialect Coach Costume Design Frank Hartley Rena Cook Hunter Dowell Board Operator Wardrobe Supervisor Joshua Christensen Carrie Greenberg Graphic Design General Management Asst. General Management Gabriella Garcia Maggie Snyder Cara Feuer Press Representative Production Stage Management Ron Lasko Theresa S. Carroll* Directed by AMY E. JONES+ * Actors' Equity OOTB is proud to hire members of + Stage Directors and Association Choreographers Society AUTHOR'S NOTE ELISE FORIER EDIE People often ask me “how much of this play is true?” The answer is, “All of it.” Also, “None of it.” All the events in this play happened to somebody. High school students across the country have been forbidden to start Gay and Straight Alliance clubs. The school picture event mentioned in this play really did happen to a child in Florida. Families across the country are being shunned, harassed and threatened by neighbors, and they suffer for allowing their transgender children to freely express their identities. -

New York Clipper (Jul 1923)

"* V J'l Mr f^^apfeff\^ "#c/x<7^ JNEW TvaRiv ^ j ^ THE QLpgST THEA1:R1CA1^ lu Hi it i ivi III ii ii tij lii ^11 in Iff fjfs ^» wr-m '' - 2 THE NEW YORK CLIPPER July 4, 1923 FOREIGN NEWS NEAR RIOT AT THOMPSON OPENING CUTTING VARIETY PRICES "AREN'T WE ALL" CLOSING REVWINC WAGNER OPERAS London, July 2.—A small-sized riot London', July 2.—Various provincial London July Z—"Aren't We All," Berlin, Jul/ 2.—The Wagner Festival witnessed the opemnK of "Phanis, the theatre centers are seriously thinking of Frederick Lonsdale's comedy will close here Committee has reached a dennite decision Egyptian," known in America as "Tbomp- lowering the prices of admission of varie^ shortly. It is not a big success here and to revive thi< great musical event next son. the Egyptian," at the Palladimn shows in an effort to stimulate more busi- theatregoers are surprised at the enthusias- year with the presentation of "Parsifal," theatre here. "Pharos" pifesents an offer- ness for the houses, which is admittedly at tic reports received from the United States "Lohengrin," and the "Meistersinger," and ing exploiting "nerve-therapy," by which a very low ebb. If the quality of the where at the Gaiety Theatre^ New York; the singers- started rehearsals today at he dauns to relieve pain by means of shows in question are kept up the move Cyril Maude is scoring one of the biggest Bayreuth. The Festival will be held from simple nerve-pressure, without the use ot is believed to be a good one for the in- hits of his entire career. -

Oscar Hammerstein II Collection

Oscar Hammerstein II Collection Guides to Special Collections in the Music Division of the Library of Congress Music Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2018 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/perform.contact Catalog Record: https://lccn.loc.gov/2014565649 Additional search options available at: https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/eadmus.mu018003 Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Music Division, 2018 Collection Summary Title: Oscar Hammerstein II Collection Span Dates: 1847-2000 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1920-1960) Call No.: ML31.H364 Creator: Hammerstein, Oscar, II, 1895-1960 Extent: 35,051 items Extent: 160 containers Extent: 72.65 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. LC Catalog record: https://lccn.loc.gov/2014565649 Summary: Oscar Hammerstein II was an American librettist, lyricist, theatrical producer and director, and grandson of the impresario Oscar Hammerstein I. The collection, which contains materials relating to Hammerstein's life and career, includes correspondence, lyric sheets and sketches, music, scripts and screenplays, production materials, speeches and writings, photographs, programs, promotional materials, printed matter, scrapbooks, clippings, memorabilia, business and financial papers, awards, and realia. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the LC Catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically. People Brill, Leighton K.--Correspondence. Buck, Pearl S. (Pearl Sydenstricker), 1892-1973--Correspondence. Buck, Pearl S. (Pearl Sydenstricker), 1892-1973. Crouse, Russel, 1893-1966. -

In Scena Tv Mercoledì 12 Dicembre 2001

Colore: Composite ----- Stampata: 11/12/01 20.29 ----- Pagina: UNITA - NAZIONALE - 26 - 12/12/01 26 in scena tv mercoledì 12 dicembre 2001 Rete4 15.45 Italia1 21.00 Raiuno 2.20 Rete4 1.15 10.000 CAMERE DA LETTO IL FUGGITIVO GORKY PARK IN QUESTA NOSTRA VITA Regia di Richard Thorpe - con Dean Mar- Con Tim Daly, Mykelti Williamson. Regia di Michael Apted - con William Hurt, Regia di John Huston - con Bette Davis, tin, Eva Bartok, Anna Maria Alberghetti. Dal mito televisivo anni ‘60 al Lee Marvin, Joanna Pacula. Usa 1983. 125 Olivia De Havilland, George Brent. Usa da non perdere Usa 1957. 114 minuti. Commedia. film con Harrison Ford, il Dot- minuti. Thriller. 1942. 97 minuti. Drammatico. Roy Hunter, re degli alberghi e tor Kimble è ancora in fuga. Ita- In una gelida mattina d'inver- Stanley lascia il promesso sposo miliardario americano, arrivato lia 1 manda in onda il remake no, nel parco Gorky di Mosca, per fuggire con un uomo che è a Roma per l’acquisto del anni 2000 del serial-cult che eb- vengono ritrovati tre cadaveri: stato sposato con sua sorella; la da vedere Grand Hotel, finisce per lasciar- be enorme successo negli anni due uomini e una donna, sfigu- loro felicità è di breve durata si coinvolgere dai capricci senti- ‘60. Rispetto alla precedente se- rati e con i polpastrelli abrasi poiché l'uomo, disilluso, si toglie mentali di quattro bellissime so- rie e al film del ‘93, la nuova per impedirne l'identificazione. la vita. La donna ritorna in fa- relle. -

Asides Magazine

2014|2015 SEASON Issue 5 TABLE OF Dear Friend, Queridos amigos: CONTENTS Welcome to Sidney Harman Bienvenidos al Sidney Harman Hall y a la producción Hall and to this evening’s de esta noche de El hombre de La Mancha. Personalmente, production of Man of La Mancha. 2 Title page The opening line of Don esta obra ocupa un espacio cálido pero enreversado en I have a personally warm and mi corazón al haber sido testigo de su nacimiento. Era 3 Musical Numbers complicated spot in my heart Quixote is as resonant in el año 1965 en la Casa de Opera Goodspeed en East for this show, since I was a Latino cultures as Dickens, Haddam, Connecticut. Estaban montando la premier 5 Cast witness to its birth. It was in 1965, at the Goodspeed Twain, or Austen might mundial, dirigida por Albert Marre. Se suponía que Opera House in East Haddam, CT. They were Albert iba a dirigir otra premier para ellos, la cual iba 7 About the Author mounting the world premiere, directed by Albert be in English literature. a presentarse en repertorio con La Mancha, pero Albert Marre. Now, Albert was supposed to direct another 10 Director’s Words world premiere for them, which was going to run In recognition of consiguió un trabajo importante en Hollywood y les recomendó a otro director: a mí. 12 The Impossible Musical in repertory with La Mancha, but he got a big job in Cervantes’ legacy, we at Hollywood, and he recommended another director. by Drew Lichtenberg That was me. STC want to extend our Así que fui a Goodspeed y dirigí la otra obra. -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability. -

Shubert Theatre Rose-Marie Program

Shubert Theatre Shubert Hoidmg Co., Lessees MESSPIS. LEE and J. J. SHUBERT Managing Directors Matinees Wednesday and Saturday ARTHUR HAMMERSTEIN Presents “ROSE-MARIE” A Musical Play with DESIREE ELLINGER And a Brilliant Cast, Including SAM ASH Book and Lyrics by Otto Harbach and -Oscar Hammerstein, 2nd Music by Rudolf Friml and Herbert Stothart Book Staged by Paul Dickey Dances Arranged by David Bennett Gowns and Costumes Designed by Charles Le Maire Settings by Gates and Morange Production Under Personal Supervision of Arthur Hammerstein Orchestra Under Direction of Charles Ruddy THE CAST (Characters as They Appear) Sergeant Malone Charles Meakins Lady Jane Beatrice Kay Black Eagle William 0. Skavlan Edward Hawley Byron Russell Emile La Flamme Paul Donah Wanda Phebe Brune Hard-Boiled Herman Houston Richards Jim Kenyon Sam Ash Rose-Marie La Flamme Desiree Ellinger Ethel Brander Cora Frye Ladies of the Ensemble—Olive Bond, Ann Ju Rika, Lillian Lyndon, Carol Andrews, Ellen de Vany, Lillian Arnold, Dorothy M. Sipley, Irene Mayo, Beatrice Fox, Ruth Scofield, Gertrude Waldon, Betty Weber, Lovey Silver, Rose W. Gray, Sophia Ross, Ursula Murray, Laurie Green, Rita Miles, Pauline Maxwell, Thea Thompson, Phoebe Hughes, Peggy McCarthy, Maude Neul, Sylvia Seville, Dolores Suarez, Vlora Fay, Dorothy Forbes, Rose Miles, Winnie Dunn, Trilby Grenet. Gentlemen of the Ensemble—Tom Chadwick, Charles Angle, Russell Griswold, John Duncan, Homer D. Wallen, Frank Dobert, Clinton Corwin, Ernest Ehler, Edward Williams, Stanley Johnson, Thomas Rider, Thomas Brady. SYNOPSIS OF SCENES Act 1. Scene 1—Lady Jane’s Hotel, Fond du Lac, Saskatchewan, Canada. Scene 2—Black Eagle’s Cabin, one hour later.