Common Primary Tumors of Bone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Osteoderm Microstructure in Doswelliids and Proterochampsids and Its Implications for Palaeobiology of Stem Archosaurs

The osteoderm microstructure in doswelliids and proterochampsids and its implications for palaeobiology of stem archosaurs DENIS A. PONCE, IGNACIO A. CERDA, JULIA B. DESOJO, and STERLING J. NESBITT Ponce, D.A., Cerda, I.A., Desojo, J.B., and Nesbitt, S.J. 2017. The osteoderm microstructure in doswelliids and proter- ochampsids and its implications for palaeobiology of stem archosaurs. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 62 (4): 819–831. Osteoderms are common in most archosauriform lineages, including basal forms, such as doswelliids and proterochamp- sids. In this survey, osteoderms of the doswelliids Doswellia kaltenbachi and Vancleavea campi, and proterochampsid Chanaresuchus bonapartei are examined to infer their palaeobiology, such as histogenesis, age estimation at death, development of external sculpturing, and palaeoecology. Doswelliid osteoderms have a trilaminar structure: two corti- ces of compact bone (external and basal) that enclose an internal core of cancellous bone. In contrast, Chanaresuchus bonapartei osteoderms are composed of entirely compact bone. The external ornamentation of Doswellia kaltenbachi is primarily formed and maintained by preferential bone growth. Conversely, a complex pattern of resorption and redepo- sition process is inferred in Archeopelta arborensis and Tarjadia ruthae. Vancleavea campi exhibits the highest degree of variation among doswelliids in its histogenesis (metaplasia), density and arrangement of vascularization and lack of sculpturing. The relatively high degree of compactness in the osteoderms of all the examined taxa is congruent with an aquatic or semi-aquatic lifestyle. In general, the osteoderm histology of doswelliids more closely resembles that of phytosaurs and pseudosuchians than that of proterochampsids. Key words: Archosauria, Doswelliidae, Protero champ sidae, palaeoecology, microanatomy, histology, Triassic, USA. -

Malignant Bone Tumors (Other Than Ewing’S): Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up by Spanish Group for Research on Sarcomas (GEIS)

Cancer Chemother Pharmacol DOI 10.1007/s00280-017-3436-0 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Malignant bone tumors (other than Ewing’s): clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up by Spanish Group for Research on Sarcomas (GEIS) Andrés Redondo1 · Silvia Bagué2 · Daniel Bernabeu1 · Eduardo Ortiz-Cruz1 · Claudia Valverde3 · Rosa Alvarez4 · Javier Martinez-Trufero5 · Jose A. Lopez-Martin6 · Raquel Correa7 · Josefina Cruz8 · Antonio Lopez-Pousa9 · Aurelio Santos10 · Xavier García del Muro11 · Javier Martin-Broto10 Received: 7 July 2017 / Accepted: 15 September 2017 © The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Primary malignant bone tumors are uncommon of a localized bone tumor, with various techniques available and heterogeneous malignancies. This document is a guide- depending on the histologic type, grade and location of the line developed by the Spanish Group for Research on Sar- tumor. Chemotherapy plays an important role in some che- coma with the participation of different specialists involved mosensitive subtypes (such as high-grade osteosarcoma). in the diagnosis and treatment of bone sarcomas. The aim is In other subtypes, historically considered chemoresistant to provide practical recommendations with the intention of (such as chordoma or giant cell tumor of bone), new targeted helping in the clinical decision-making process. The diag- therapies have emerged recently, with a very significant effi- nosis and treatment of bone tumors requires a multidiscipli- cacy in the case of denosumab. Radiation therapy is usually nary approach, involving as a minimum pathologists, radi- necessary in the treatment of chordoma and sometimes of ologists, surgeons, and radiation and medical oncologists. other bone tumors. Early referral to a specialist center could improve patients’ survival. -

Nomina Histologica Veterinaria, First Edition

NOMINA HISTOLOGICA VETERINARIA Submitted by the International Committee on Veterinary Histological Nomenclature (ICVHN) to the World Association of Veterinary Anatomists Published on the website of the World Association of Veterinary Anatomists www.wava-amav.org 2017 CONTENTS Introduction i Principles of term construction in N.H.V. iii Cytologia – Cytology 1 Textus epithelialis – Epithelial tissue 10 Textus connectivus – Connective tissue 13 Sanguis et Lympha – Blood and Lymph 17 Textus muscularis – Muscle tissue 19 Textus nervosus – Nerve tissue 20 Splanchnologia – Viscera 23 Systema digestorium – Digestive system 24 Systema respiratorium – Respiratory system 32 Systema urinarium – Urinary system 35 Organa genitalia masculina – Male genital system 38 Organa genitalia feminina – Female genital system 42 Systema endocrinum – Endocrine system 45 Systema cardiovasculare et lymphaticum [Angiologia] – Cardiovascular and lymphatic system 47 Systema nervosum – Nervous system 52 Receptores sensorii et Organa sensuum – Sensory receptors and Sense organs 58 Integumentum – Integument 64 INTRODUCTION The preparations leading to the publication of the present first edition of the Nomina Histologica Veterinaria has a long history spanning more than 50 years. Under the auspices of the World Association of Veterinary Anatomists (W.A.V.A.), the International Committee on Veterinary Anatomical Nomenclature (I.C.V.A.N.) appointed in Giessen, 1965, a Subcommittee on Histology and Embryology which started a working relation with the Subcommittee on Histology of the former International Anatomical Nomenclature Committee. In Mexico City, 1971, this Subcommittee presented a document entitled Nomina Histologica Veterinaria: A Working Draft as a basis for the continued work of the newly-appointed Subcommittee on Histological Nomenclature. This resulted in the editing of the Nomina Histologica Veterinaria: A Working Draft II (Toulouse, 1974), followed by preparations for publication of a Nomina Histologica Veterinaria. -

Biology of Bone Repair

Biology of Bone Repair J. Scott Broderick, MD Original Author: Timothy McHenry, MD; March 2004 New Author: J. Scott Broderick, MD; Revised November 2005 Types of Bone • Lamellar Bone – Collagen fibers arranged in parallel layers – Normal adult bone • Woven Bone (non-lamellar) – Randomly oriented collagen fibers – In adults, seen at sites of fracture healing, tendon or ligament attachment and in pathological conditions Lamellar Bone • Cortical bone – Comprised of osteons (Haversian systems) – Osteons communicate with medullary cavity by Volkmann’s canals Picture courtesy Gwen Childs, PhD. Haversian System osteocyte osteon Picture courtesy Gwen Childs, PhD. Haversian Volkmann’s canal canal Lamellar Bone • Cancellous bone (trabecular or spongy bone) – Bony struts (trabeculae) that are oriented in direction of the greatest stress Woven Bone • Coarse with random orientation • Weaker than lamellar bone • Normally remodeled to lamellar bone Figure from Rockwood and Green’s: Fractures in Adults, 4th ed Bone Composition • Cells – Osteocytes – Osteoblasts – Osteoclasts • Extracellular Matrix – Organic (35%) • Collagen (type I) 90% • Osteocalcin, osteonectin, proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans, lipids (ground substance) – Inorganic (65%) • Primarily hydroxyapatite Ca5(PO4)3(OH)2 Osteoblasts • Derived from mesenchymal stem cells • Line the surface of the bone and produce osteoid • Immediate precursor is fibroblast-like Picture courtesy Gwen Childs, PhD. preosteoblasts Osteocytes • Osteoblasts surrounded by bone matrix – trapped in lacunae • Function -

Sclerostin Inhibition Alleviates Breast Cancer–Induced Bone Metastases and Muscle Weakness

Sclerostin inhibition alleviates breast cancer–induced bone metastases and muscle weakness Eric Hesse, … , Hiroaki Saito, Hanna Taipaleenmäki JCI Insight. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.125543. Research In-Press Preview Bone biology Oncology Breast cancer bone metastases often cause a debilitating non-curable condition with osteolytic lesions, muscle weakness and a high mortality. Current treatment comprises chemotherapy, irradiation, surgery and anti-resorptive drugs that restrict but do not revert bone destruction. In metastatic breast cancer cells, we determined the expression of sclerostin, a soluble Wnt inhibitor that represses osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. In mice with breast cancer bone metastases, pharmacological inhibition of sclerostin using an anti-sclerostin antibody (Scl-Ab) reduced metastases without tumor cell dissemination to other distant sites. Sclerostin inhibition prevented the cancer-induced bone destruction by augmenting osteoblast-mediated bone formation and reducing osteoclast-dependent bone resorption. During advanced disease, NF-κB and p38 signaling was increased in muscles in a TGF-β1-dependent manner, causing muscle fiber atrophy, muscle weakness and tissue regeneration with an increase in Pax7-positive satellite cells. Scl-Ab treatment restored NF-κB and p38 signaling, the abundance of Pax7-positive cells and ultimately muscle function. These effects improved the overall health condition and expanded the life span of cancer-bearing mice. Together, these results demonstrate that pharmacological -

Primary Bone Cancer a Guide for People Affected by Cancer

Cancer information fact sheet Understanding Primary Bone Cancer A guide for people affected by cancer This fact sheet has been prepared What is bone cancer? to help you understand more about Bone cancer can develop as either a primary or primary bone cancer, also known as secondary cancer. The two types are different and bone sarcoma. In this fact sheet we this fact sheet is only about primary bone cancer. use the term bone cancer, and include general information about how bone • Primary bone cancer – means that the cancer cancer is diagnosed and treated. starts in a bone. It may develop on the surface, in the outer layer or from the centre of the bone. As a tumour grows, cancer cells multiply and destroy The bones the bone. If left untreated, primary bone cancer A typical healthy person has over 200 bones, which: can spread to other parts of the body. • support and protect internal organs • are attached to muscles to allow movement • Secondary (metastatic) bone cancer – means • contain bone marrow, which produces that the cancer started in another part of the body and stores new blood cells (e.g. breast or lung) and has spread to the bones. • store proteins, minerals and nutrients, such See our fact sheet on secondary bone cancer. as calcium. Bones are made up of different parts, including How common is bone cancer? a hard outer layer (known as cortical or compact Bone cancer is rare. About 250 Australians are bone) and a spongy inner core (known as trabecular diagnosed with primary bone cancer each year.1 or cancellous bone). -

What Is Bone Cancer?

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 About Bone Cancer Overview and Types If you have been diagnosed with bone cancer or are worried about it, you likely have a lot of questions. Learning some basics is a good place to start. ● What Is Bone Cancer? Research and Statistics See the latest estimates for new cases of bone cancer and deaths in the US and what research is currently being done. ● Key Statistics About Bone Cancer ● What’s New in Bone Cancer Research? What Is Bone Cancer? The information here focuses on primary bone cancers (cancers that start in bones) that most often are seen in adults. Information on Osteosarcoma1, Ewing Tumors (Ewing sarcomas)2, and Bone Metastases3 is covered separately. Cancer starts when cells begin to grow out of control. Cells in nearly any part of the body can become cancer, and can then spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body. To learn more about cancer and how it starts and spreads, see What Is Cancer?4 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Bone cancer is an uncommon type of cancer that begins when cells in the bone start to grow out of control. To understand bone cancer, it helps to know a little about normal bone tissue. Bone is the supporting framework for your body. The hard, outer layer of bones is made of compact (cortical) bone, which covers the lighter spongy (trabecular) bone inside. The outside of the bone is covered with fibrous tissue called periosteum. Some bones have a space inside called the medullary cavity, which contains the soft, spongy tissue called bone marrow(discussed below). -

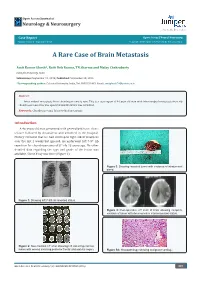

A Rare Case of Brain Metastasis

Open Access Journal of Neurology & Neurosurgery . key to the Researchers Case Report Open Access J Neurol Neurosurg Volume 1 Issue 2 - September 2016 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Katarina Matic A Rare Case of Brain Metastasis Amit Kumar Ghosh*, Rafit Deb Barma, TN Sharma and Malay Chakrabarty Calcutta University, India Submission: September 19, 2016; Published: September 28, 2016 *Corresponding author: Calcutta University, India, Tel: ; Email: Abstract Intracerebral metastasis from chondrosarcoma is rare. This is a case report of 46 year old man with intracerebral metastasis from rib chondrosarcoma who was operated and literature was reviewed. Keywords: Chondrosarcoma; Intracerebral metastasis Introduction A 46 years old man presented with generalised tonic clonic seizure followed by drowsiness and admitted in the hospital. History revealed that he had developed right sided weakness over the last 2 weeks but ignored. He underwent left 7-9th rib resection for chondrosarcoma of 8th rib 13 years ago. No other detailed data regarding the type and grade of the lesion was available. Chest X-ray was done (Figure 1). Figure 3: Showing resected tumor with evidence of intratumoral bleed. Figure 1: Showing left 7-9th rib resected status. Figure 4: Post-operative CT scan of brain showing complete excision of tumor with decompresive craniectomised status. Figure 2: Non-contrast CT scan showing left sided hyperdense lesion with edema involving posterior frontal and parietal region. Figure 5A: Histopathology showing malignant cartilage. Open Access J Neurol Neurosurg 1(2): OAJNN.MS.ID.55560 (2016) 001 Open Access Journal of Neurology & Neurosurgery differentiated chondrosarcoma (Figure 5A, 5B, 5C, 5D, 5E). -

Bone & Soft Tissue

14A ANNUAL MEETING ABSTRACTS and testicular atrophy with aspermatogenia (negative OCT3/OCT4 stain). There was 47 Comparison of Autopsy Findings of 2009 Pandemic Influenza evidence of acute multifocal bronchopneumonia and congestive heart failure. He carried A (H1N1) with Seasonal Influenza in Four Pediatric Patients two heterozygous mutations in ALMS1: 11316_11319delAGAG; R3772fs in exon 16 B Xu, JJ Woytash, D Vertes. State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY; Erie and 8164C>T ter; R2722X in exon 10. County Medical Examiner’s Office, Buffalo, NY. Conclusions: This report describes previously undefined cardiac abnormalities in this Background: The swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus that emerged in humans rare multisystem disorder. Myofibrillar disarray is probably directly linked to ALMS1 in early 2009 has reached pandemic proportions and cause over 120 pediatric deaths mutation, while fibrosis in multiple organs may be a secondary phenomenon to gene nationwide. Studies in animal models have shown that the 2009 H1N1 influenza virus alteration. Whether and how intracellular trafficking or related signals lead to cardiac is more pathogenic than seasonal A virus, with more extensive virus replication and dysfunction is a subject for further research. shedding occurring the respiratory tract. Design: We report four cases of influenza A-associated deaths (two pandemic and two 45 Sudden Cardiac Death in Young Adults: An Audit of Coronial seasonal) in persons less than fifteen years of age who had no underlying health issues. Autopsy Findings Autopsy finding on isolation of virus from various tissue specimen, cocurrent bacterial A Treacy, A Roy, R Margey, JC O’Keane, J Galvin, A Fabre. -

Osteosarcoma

disease • canine lymphoma • brain tumor • congestive heart failure • feline lymphoma • primary lung tumor • mast cell tumor • kidney disease • transitional cell carcinoma • degenerative myelopathy • cognitive dysfunction syndrome • liver disease • seizures • osteosarcoma • hemangiosarcoma • nasal tumorsdiabetes • Common Signs of Pain • hyperadrenocorticism • hyperthyroidism • osteoarthritis • vestibular disease • canine lymphoma • brain tumor • congestive heart failure • feline lymphoma • Panting • Licking sore spot • primary lung tumor • mast cell tumor • kidney disease • transitional cell • Lameness • Muscle atrophy carcinoma • degenerative myelopathy • cognitive dysfunction syndrome • liver • Difficulty sleeping • Decreased appetite disease • seizures • osteosarcoma • hemangiosarcoma • nasal tumorsdiabetes • • Pacing • Vocalizing/yowling • hyperadrenocorticism • hyperthyroidism • osteoarthritis • vestibular disease • canine lymphoma • brain tumor • congestive heart failure • feline lymphoma • Abnormal posture • Reclusive Behavior • primary lung tumor • mast cell tumor • kidney disease • transitional cell • Body tensing • Aggressive Behavior carcinoma • degenerative myelopathy • cognitive dysfunction syndrome • liver • Poor grooming habits • Avoiding stairs/jumping disease • seizures • osteosarcoma • hemangiosarcoma • nasal tumorsdiabetes • • Tucked tail • Depressed • hyperadrenocorticism • hyperthyroidism • osteoarthritis • vestibular disease • Dilated Pupils • Unable to stand • canine lymphoma • brain tumor • congestive heart failure -

MSK News Summer 2021 Download

SUMMER 2021 SPECIAL ISSUE MSKNewsMEMORIAL SLOAN KETTERING CANCER CENTER Defeating Cancer’s Spread On the 50th anniversary of the War on Cancer, this SPECIAL ISSUE focuses on metastasis: What’s available now — and on the horizon — for patients like Ilene Thompson facing advanced disease. ALSO INSIDE: A Major Advance for Prostate Cancer Patients Seed and Soil: A Cancer Cell’s Journey How to Outsmart Tumor Evolution TABLE OF Dear MSK Community, These are the four most frightening words for a patient to hear: “Your cancer is back.” CONTENTS As we mark the 50th year of the War on Cancer and look to the future, our mission at Memorial Sloan Kettering is nothing less than conquering the most urgent challenge: preventing cancer’s spread. Also called metastasis, it causes 90 percent of cancer deaths. It’s why we are devoting this entire issue to reporting on how we offer hope and help to patients whose cancer has spread. 12 Metastasis: A Roadmap In the clinic, we are developing more targeted drugs, more precise radiation, and more sophisticated See the journey of a cancer cell as it transforms surgical techniques to treat our patients. In the lab, we are learning more every day about why and travels through the body. cancer cells metastasize and how to stop them. Our vision to save more lives requires a commitment to hire and train the brightest minds Multiplying the Army and a significant investment in four key areas of technology, which are already bringing about 17 astonishing advances: of Cancer-Fighting Immune Cells • Better models to study cancer: Conducting research in mice is time-consuming and doesn’t Learn about a new technology taking necessarily reflect cancer biology in humans. -

Current Overview of Treatment for Metastatic Bone Disease

Review Current Overview of Treatment for Metastatic Bone Disease Shinji Tsukamoto 1,* , Akira Kido 2, Yasuhito Tanaka 1 , Giancarlo Facchini 3 , Giuliano Peta 3 , Giuseppe Rossi 3 and Andreas F. Mavrogenis 4 1 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Nara Medical University, 840, Shijo-cho, Kashihara 634-8521, Nara, Japan; [email protected] 2 Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Nara Medical University, 840, Shijo-cho, Kashihara 634-8521, Nara, Japan; [email protected] 3 Department of Radiology and Interventional Radiology, IRCCS Istituto Ortopedico Rizzoli, Via Pupilli 1, 40136 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] (G.F.); [email protected] (G.P.); [email protected] (G.R.) 4 First Department of Orthopaedics, School of Medicine, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, 41 Ventouri Street, 15562 Athens, Greece; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-744-22-3051 Abstract: The number of patients with bone metastasis increases as medical management and surgery improve the overall survival of patients with cancer. Bone metastasis can cause skeletal complications, including bone pain, pathological fractures, spinal cord or nerve root compression, and hypercalcemia. Before initiation of treatment for bone metastasis, it is important to exclude primary bone malignancy, which would require a completely different therapeutic approach. It is essential to select surgical methods considering the patient’s prognosis, quality of life, postoperative function, and risk of postoperative complications.