Orienteering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites Street Address Index

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA INVENTORY OF HISTORIC SITES STREET ADDRESS INDEX UPDATED TO OCTOBER 31, 2014 NUMBERED STREETS Half Street, SW 1360 ........................................................................................ Syphax School 1st Street, NE between East Capitol Street and Maryland Avenue ................ Supreme Court 100 block ................................................................................. Capitol Hill HD between Constitution Avenue and C Street, west side ............ Senate Office Building and M Street, southeast corner ................................................ Woodward & Lothrop Warehouse 1st Street, NW 320 .......................................................................................... Federal Home Loan Bank Board 2122 ........................................................................................ Samuel Gompers House 2400 ........................................................................................ Fire Alarm Headquarters between Bryant Street and Michigan Avenue ......................... McMillan Park Reservoir 1st Street, SE between East Capitol Street and Independence Avenue .......... Library of Congress between Independence Avenue and C Street, west side .......... House Office Building 300 block, even numbers ......................................................... Capitol Hill HD 400 through 500 blocks ........................................................... Capitol Hill HD 1st Street, SW 734 ......................................................................................... -

Waiver and Release, Ver: 9-28-07, Page 1 of 2 WAIVER and RELEASE Auburn Ski Club Associates, Inc. Auburn Ski Club, Inc. Traini

Family Form WAIVER AND RELEASE Auburn Ski Club Associates, Inc. Auburn Ski Club, Inc. Training Center I/We, the undersigned, and/or parent or legal guardian of a minor, desiring to participate in the Alpine and Nordic programs of the Auburn Ski Club Associates, Inc. (“Associates”) hereby acknowledge that the use by myself (each undersigned adult participant) or my/our minor child(ren) of the facilities, equipment or programs of Associates at the Auburn Ski Club Training Center, Boreal Mountain Resort, Alpine Meadows Ski Area, Northstar at Tahoe and other ski areas is permissive only and is subject to the terms of this Release. The facility and other properties utilized by the Associates are owned by a separate corporation, namely Auburn Ski Club, Inc. (“ASC”), and the waivers and releases given pursuant to this Agreement extend to, and are for the benefit of, the Associates, ASC and the other Released Parties that are identified below. This Agreement contains the entire agreement and understanding between the Released Parties and the undersigned concerning the subject matter of this Agreement and supersedes all prior agreements, terms, understandings, conditions, representations and warranties, whether written or oral. I/We acknowledge that the sport of skiing, both Nordic and Alpine, biathlon, snowboarding, orienteering, ski jumping, ski racing, terrain park activities and other related events and activities hosted by Associates, ASC, and/or the Training Center (including, without limitation, weight training, off-snow physical fitness conditioning, fitness testing and the discharge of firearms in connection with biathlon programs) are action sports and related activities which carry a significant risk of personal injury and even death. -

OUTDOOR EDUCATION (OUT) Credits: 4 Voluntary Pursuits in the Outdoors Have Defined American Culture Since # Course Numbers with the # Symbol Included (E.G

University of New Hampshire 1 OUT 515 - History of Outdoor Pursuits in North America OUTDOOR EDUCATION (OUT) Credits: 4 Voluntary pursuits in the outdoors have defined American culture since # Course numbers with the # symbol included (e.g. #400) have not the early 17th century. Over the past 400 years, activities in outdoor been taught in the last 3 years. recreation an education have reflected Americans' spiritual aspirations, imperial ambitions, social concerns, and demographic changes. This OUT 407B - Introduction to Outdoor Education & Leadership - Three course will give students the opportunity to learn how Americans' Season Experiences experiences in the outdoors have influenced and been influenced by Credits: 2 major historical developments of the 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th, and early An exploration of three-season adventure programs and career 21st centuries. This course is cross-listed with RMP 515. opportunities in the outdoor field. Students will be introduced to a variety Attributes: Historical Perspectives(Disc) of on-campus outdoor pursuits programming in spring, summer, and fall, Equivalent(s): KIN 515, RMP 515 including hiking, orienteering, climbing, and watersports. An emphasis on Grade Mode: Letter Grade experiential teaching and learning will help students understand essential OUT 539 - Artificial Climbing Wall Management elements in program planning, administration and risk management. You Credits: 2 will examine current trends in public participation in three-season outdoor The primary purpose of this course is an introduction -

2018 Basic Alpine Climbing Course Student Handbook

Mountaineers Basic Alpine Climbing Course 2018 Student Handbook 2018 Basic Alpine Climbing Course Student Handbook Allison Swanson [Basic Course Chair] Cebe Wallace [Meet and Greet, Reunion] Diane Gaddis [SIG Organization] Glenn Eades [Graduation] Jan Abendroth [Field Trips] Jeneca Bowe [Lectures] Jared Bowe [Student Tracking] Jim Nelson [Alpine Fashionista, North Cascades Connoisseur] Liana Robertshaw [Basic Climbs] Vineeth Madhusudanan [Enrollment] Fred Beckey, photograph in High Adventure, by Ira Spring, 1951 In loving memory Fred Page Beckey 1 [January 14, 1923 – October 30, 2017] Mountaineers Basic Alpine Climbing Course 2018 Student Handbook 2018 BASIC ALPINE CLIMBING COURSE STUDENT HANDBOOK COURSE OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................................ 3 Class Meetings ............................................................................................................................ 3 Field Trips ................................................................................................................................... 4 Small Instructional Group (SIG) ................................................................................................. 5 Skills Practice Nights .................................................................................................................. 5 References ................................................................................................................................... 6 Three additional -

An Introduction to Trail Orienteering for Organisers, Planners and Participants

IntrO Paralympic class and Open class competitors at WTOC 2013 in France An introduction to trail orienteering for organisers, planners and participants. Sept 2013 1. Introduction This manual is for organisers, planners and participants unfamiliar with trail orienteering or wishing to refresh their understanding of it. It deals with IntrO, which is the name given to a simplified introductory form of trail orienteering. Those reading this manual are almost certainly familiar with orienteering, as generally practised, and may have some idea about trail orienteering. But there can be misconceptions, so the essential elements of the discipline are re-stated here. Trail orienteering is a world sport FootO MTBO SkiO TrailO TrailO is one of the four disciplines of orienteering, governed by the International Orienteering Federation, based in Helsinki, Finland. All four disciples have annual world championships. TrailO is not yet as widespread as FootO but extends from the USA to Japan (via Europe). Trail orienteering is a sport for all Do not misinterpret the official trailO logo. Although the discipline was specially designed as a non-athletic, intellectual version of orienteering, in order that those in wheelchairs and others with mobility difficulties can take full part in competition, so can the able-bodied. TrailO events are always open to all without regard to age, gender or mobility impairment, but may also have a closed ‘Paralympic’ class, usually on the same course. The popularity of trailO is such that the majority of participants are able-bodied including world champion foot orienteers. It is particularly attractive to those orienteers who, for whatever reason, find foot orienteering becoming too physical but wish to continue participating in orienteering. -

Silva Manual- Mirror Sighting Compasses

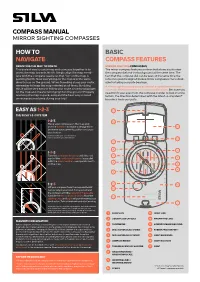

COMPASSHOW MANUAL TO MIRROR SIGHTING COMPASSES NAVIGATEHOW TO BASIC NAVIGATE COMPASS FEATURES HOWORIENTING TO THE MAP TO NORTH MIRROR SIGHTING COMPASSES EASYThe easiest way to use a map and compass AS together is to The mirror compass features a mirror that allows you to view orient the map towards North. Simply align the map merid- the compass dial and the background at the same time. The ians with the compass needle so that “up” on the map is fact that the compass dial can be seen at the same time the pointing North. Now everything on the map is in the same reference point is aligned makes mirror compasses more desir- NAVIGATEdirection as on the ground. When travelling along your route, able for taking accurate bearings. remember to keep the map oriented at all times. By doing A mirror-sighting compass is at its best in open terrain where 1-2-3this it will be very easy to follow your route since turning right you must determine direction over long distances. Because you on the map also means turning right on the ground! Properly needn’t lift your eyes from the compass in order to look into the orienting1-2-3 the map is quick, easy1-2 and-3 the best way to avoid1-2- 3 terrain, the direction determined with the Silva 1-2-3 System® HOW TOunnecessaryPlace your compass mistakes on the map duringTurn your the compass trip! housing until the Lift your compass frombecomes the map more accurate. and use the baseline to make a red part of the north/south arrow and hold it horizontally in your EASYstraight line between AS your current is parallel with the map meridians, hand. -

Environmental Geocaching: Learning Through Nature and Technology

WSFNR-20-67A September 2020 ENVIRONMENTAL GEOCACHING: LEARNING THROUGH NATURE AND TECHNOLOGY Brady Self, Associate Extension Professor, Department of Forestry, Mississippi State University Jason Gordon, Assistant Professor, Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia Parents, natural resource professionals and enthusiasts, and youth coordinators often find themselves at a loss when trying to encour- age younger generations to take up outdoor pastimes. The allure of electronic technology, team sports, combined with time availability of parents sometimes limits overall involve- ment of today’s youth in more traditional outdoor activities. In this fast-paced world, learning about nature and what occurs in the forest seems to be losing ground when competing for adolescents’ interest and time. The good news is that there are still many op- portunities to involve youth in the outdoors. The game of geocaching provides one of these opportunities. Geocaching offers learning and fun while spending time in nature. Geocaching is an outdoor treasure hunting game that operates much like the scavenger hunting that many parents and grandparents remember from their youth. The game adds the use of GPS technology (either a dedi- cated receiver unit, or more commonly, a GPS-enabled smartphone) to guide players to locations where individual geocaches are hidden. Clues are then used to search for the geocache. Geocaches can be selected or created with a theme focused on learning about forests, wildlife, and other natural resources. These experiences are then shared online in the geocaching community. The overall objective of the activity is to guide participants to places of significance where they have the opportu- nity to learn something about that particular location or geocache topic. -

Orienteering at Brighton Woods

ORIENTEERING AT BRIGHTON WOODS • There are eight numbered posts (controls) for the orienteering course at Brighton Woods. Each has a number that corresponds to the number on the Brighton Woods Orienteering Map, but they may be found in any order. • It is easier to go directly from control to control when there is less ground cover: late fall, winter, and early spring. Long pants are recommended because of the poison ivy and ticks. 1. NUMBERED CONTROL DESCRIPTIONS 1. Sports Field 2. Southwest End of Pipeline Clearing 3. Amphitheater 4. The Bridge 5. Head of Trail 6. Rock Outcropping 7. River 8. Northeast End of Pipeline Clearing 2. PLOTTING THE COURSE • Find control #1 on the map.(The Sports Field.) • On the map, line up one edge of the compass from where you are (Control #1: Sports Field) to where you want to go, (Control # 2: Southwest End of Pipeline Clearing) making sure the direction-of-travel arrow faces your destination point. (This is the first secret of orienteering.) • Rotate the housing of the compassso that the gridlines are parallel to the North - South gridlines on the orienteering map. The cardinal point N must be at the North side of your map. (This is the second secret to orienteering.) • Readyour bearing in degrees at the Bearing Index. (At the Direction-of- Travel line, or the "Read Bearing Here" mark.) The number of degrees is * • Do not rotate the housing again until you need a new bearing! 3. FINDING THE FIXED CONTROLS • Stand directly in front of the control #1 and hold your compass level and squarely in front of your body. -

IOF Control Descriptions 2018

International Specifi cation for Control Descriptions INTERNATIONAL ORIENTEERING FEDERATION 2018 INTERNATIONAL ORIENTEERING FEDERATION International Orienteering Federation Drottninggatan 47, 3 1/2 tr. SE-65225 Karlstad Sweden http://www.orienteering.org IOF RULES COMMISSION: David Rosen (chairman), Barry McCrae, Felix Büchi Editor: Barry Elkington Artwork based on the 1990 edition with additional drawings by Matthew Cook (2004, 2018). Map sections by Jukka Liikari. Layout: Martin Hammarberg, Adshape AB. IOF Control Descriptions Major Changes to the 2004 version: 1) Optional extra line showing the distance to the start triangle from the timed start. 2) New symbols introduced for Trench, Out of Bounds Area. 3) Bend moved from Column G to Column F. 4) Removal of symbol for Radio or TV control. 5) Names and descriptions brought into line with the ISOM 2017 terminology where appro- priate. 6) Renumbering of symbols to cater for additions and deletions. 7) A number of minor changes throughout the text in order to provide further clarification as to the use of specific symbols. 2 International Specification for Control Descriptions - 2018 Introduction Orienteering is a worldwide sport. It is the aim of the IOF control description symbols to provide a standard means for orienteers from all countries to be able to understand control descriptions without ambiguity or the need for language translation. This booklet shows how the symbols can be used to do this. How IOF control descriptions work The purpose of a control description is to give greater precision to the picture given by the map of the control feature, and to indicate the location of the control flag in relation to this feature, thereby helping the competitor to better visualise the control site. -

Through the Years: the History of the Harmon Choral Associates

The HistoryThrough of the George Washington the University Years: Choral Program Please note: An index of pictures begins on page 48 Introduction One Saturday evening in the spring of 1986, Winfield Weitzel stood before a group of dinner guests assembled at the Marvin Center and told of the night The George Washington University Glee Club won first place in the National Intercollegiate Glee Club Contest held at Carnegie Hall. That year was 1930 and, yes, GW surpassed the glee clubs of Yale and Princeton, Columbia and Dartmouth in the competi- tion... a night to remember! The 1930 concert program had never been placed in the University Archives, but Weitzels copy occupied a prominent place in the evenings exhibit of choral memorabilia. The event at which Weitzel was speaking was the March 1986 Harmon Choral Reunion. Drawn by a camaraderie developed in the tradition of choral singing and wishing to honor their leader of more than 40 years, Dr. Robert Howe Harmon, GW choristers traveled long distances to the reunion. There were 239 guests in attendance at the banquet and more than 500 crowded the Dorothy Betts Marvin Theatre later that evening to hear student and alumni voices join together in a rousing Its A Grand Night For Singing. They were celebrating a grand tradition at GW the tradition of choral singing which dates to the turn of the century and has taken the Universitys name to the far corners of the earth. One of those places was the South Pacific, where Traveling Troubadours members Dick Hedges, Steve Andersen, Dave Lum, John Parker, Wade Currier, Dick Randall, Sue Farquharson Law, Joan Haag Osborne and Rosemary Glenn found themselves in 1950. -

NPS Form 10-900 (Rev

NPS Form 10-900 (Rev. 11-90) OMB No. 10024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties or districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to compete all items. 1. Name of Property Historic name: MUNSON HALL APARTMENT BUILDING Other names/site number: MUNSON HALL 2. Location Street & Number: 2212 I Street, N.W. [ ] Not for Publication City or town: Washington [ ] Vicinity State: D.C. Code: 001 County Code: Zip Code: 20037 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this [ ] nomination [ ] request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property [ ] meets [ ] does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant [ ] nationally [ ] statewide [ ] locally. ([ ] See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of certifying official/Title Date State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property [ ] meets [ ] does not meet the National Register criteria. -

District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites Street Address Index

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA INVENTORY OF HISTORIC SITES STREET ADDRESS INDEX UPDATED TO JANUARY 31, 2015 NUMBERED STREETS Half Street, SW 1360 ........................................................................................ Syphax School 1st Street, NE between East Capitol Street and Maryland Avenue ................ Supreme Court 100 block ................................................................................. Capitol Hill HD between Constitution Avenue and C Street, west side ............ Senate Office Building and M Street, southeast corner ................................................ Woodward & Lothrop Warehouse 1st Street, NW 320 .......................................................................................... Federal Home Loan Bank Board 2122 ........................................................................................ Samuel Gompers House 2400 ........................................................................................ Fire Alarm Headquarters between Bryant Street and Michigan Avenue ......................... McMillan Park Reservoir 1st Street, SE between East Capitol Street and Independence Avenue .......... Library of Congress between Independence Avenue and C Street, west side .......... House Office Building 300 block, even numbers ......................................................... Capitol Hill HD 400 through 500 blocks ........................................................... Capitol Hill HD 1st Street, SW 734 .........................................................................................