Land Navigation, Compass Skills & Orienteering = Pathfinding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beacon Hill Trail System Master Plan

Beacon Hill Trail System Draft Concept Plan May 2009 Beacon Hill Trail System Draft Concept Plan • February 2009 Acknowledgments Lead Organization Northeast Community Fat Tire Trail Riders Club Center Land Managers and Owners Spokane City Parks and Recreation Avista Department Matt and Cory Collin Spokane City Bicycle Pete Rayner Advisory Board Spokane Parks and Recreation Department Spokane County - Engineering Spokane County Parks, Recreation and Golf Department Spokane County Parks, Recreation and Golf Brian Walker, Tomlinson NAI Spokane Mountaineers Molly and Phil Zammit Spokane Regional Health District Beacon Hill Advisory Group Washington State University Avista Washington State Department of Transportation Beacon Hill Events Center, Pete Rayner West Valley School District Fat Tire Trail Riders Club Spokane Police Inland Northwest Trails Coalition Charrette Sponsors International Mountain Bicycling Association Safeway Minnehaha Neighborhood Council Starbucks Mountain Gear Northeast Community Center Fitness Fanatics REI Dr. Ed Jones Spokane Parks & Recreation Department Bicycle Butler Spokane County Parks, Recreation and Golf Department Instant Benefits Spokane Regional Health District Cache Advance WheelSport East Out There Monthly Winterport Ski Shop Mountain Gear Molly and Phil Zammit, Private Landowners REI Organizations that Participated in the Wheel Sport East & Wheel Sport South Charrette Vince Poff, Specialized Bikes American Society of Landscape Architects (Washington North Division Bike and Ski Chapter) Technical Assistance -

Waiver and Release, Ver: 9-28-07, Page 1 of 2 WAIVER and RELEASE Auburn Ski Club Associates, Inc. Auburn Ski Club, Inc. Traini

Family Form WAIVER AND RELEASE Auburn Ski Club Associates, Inc. Auburn Ski Club, Inc. Training Center I/We, the undersigned, and/or parent or legal guardian of a minor, desiring to participate in the Alpine and Nordic programs of the Auburn Ski Club Associates, Inc. (“Associates”) hereby acknowledge that the use by myself (each undersigned adult participant) or my/our minor child(ren) of the facilities, equipment or programs of Associates at the Auburn Ski Club Training Center, Boreal Mountain Resort, Alpine Meadows Ski Area, Northstar at Tahoe and other ski areas is permissive only and is subject to the terms of this Release. The facility and other properties utilized by the Associates are owned by a separate corporation, namely Auburn Ski Club, Inc. (“ASC”), and the waivers and releases given pursuant to this Agreement extend to, and are for the benefit of, the Associates, ASC and the other Released Parties that are identified below. This Agreement contains the entire agreement and understanding between the Released Parties and the undersigned concerning the subject matter of this Agreement and supersedes all prior agreements, terms, understandings, conditions, representations and warranties, whether written or oral. I/We acknowledge that the sport of skiing, both Nordic and Alpine, biathlon, snowboarding, orienteering, ski jumping, ski racing, terrain park activities and other related events and activities hosted by Associates, ASC, and/or the Training Center (including, without limitation, weight training, off-snow physical fitness conditioning, fitness testing and the discharge of firearms in connection with biathlon programs) are action sports and related activities which carry a significant risk of personal injury and even death. -

The Auckland

The Auckland March 2009 The Auckland Orienteer March 2009 2 Editorial Note the info for the OY competition will be provided in the April edition – I hope. The exercise below refers to the control descriptions on the front cover Answers follow later in the newsletter. 1. What is the climb of this course? 2. On what feature is the start triangle? 3. What information is provided in the finish box? 4. Give the English language description for each of controls 1 to 7. John Editorial Bits Next Issue: April 2009 Contributions to this newsletter are welcome – opinions, information, images, anecdotes and cartoons. Please email contributions to John Powell at [email protected] or mail to 11 Cathcart Close, Pukekohe, by March 20. Contributions may be edited or abridged by the editor. Distribution If you change your address please contact your club membership officer or Stephen Reynolds at 09 358 854 or [email protected] Sender Auckland Orienteering Association, 132 Waikoukou Valley Road, RD2, Waimauku The Auckland Orienteer is the monthly magazine of the Auckland Orienteering Association. It is produced monthly, except January, and is available online from www.nworienteering.org.nz. Other orienteering related publications are welcome to draw material from the magazine although credit is asked for both the author, if stated, and the magazine. AOA newsletters are available on the NW website along with an index to articles. Some of these articles are particularly relevant to novice orienteers and experienced orienteers who are new to orienteering in the Auckland region. Notices World Games Trials To be held in Chinese Taipei on July 16-26, 2009. -

OUTDOOR EDUCATION (OUT) Credits: 4 Voluntary Pursuits in the Outdoors Have Defined American Culture Since # Course Numbers with the # Symbol Included (E.G

University of New Hampshire 1 OUT 515 - History of Outdoor Pursuits in North America OUTDOOR EDUCATION (OUT) Credits: 4 Voluntary pursuits in the outdoors have defined American culture since # Course numbers with the # symbol included (e.g. #400) have not the early 17th century. Over the past 400 years, activities in outdoor been taught in the last 3 years. recreation an education have reflected Americans' spiritual aspirations, imperial ambitions, social concerns, and demographic changes. This OUT 407B - Introduction to Outdoor Education & Leadership - Three course will give students the opportunity to learn how Americans' Season Experiences experiences in the outdoors have influenced and been influenced by Credits: 2 major historical developments of the 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th, and early An exploration of three-season adventure programs and career 21st centuries. This course is cross-listed with RMP 515. opportunities in the outdoor field. Students will be introduced to a variety Attributes: Historical Perspectives(Disc) of on-campus outdoor pursuits programming in spring, summer, and fall, Equivalent(s): KIN 515, RMP 515 including hiking, orienteering, climbing, and watersports. An emphasis on Grade Mode: Letter Grade experiential teaching and learning will help students understand essential OUT 539 - Artificial Climbing Wall Management elements in program planning, administration and risk management. You Credits: 2 will examine current trends in public participation in three-season outdoor The primary purpose of this course is an introduction -

BLAZING YOUR TRAIL Grades 5-12 2 Hours

BLAZING YOUR TRAIL Grades 5-12 2 Hours Thank you for booking our “Blazing Your Trail” program at Fort Whyte Alive. This program is designed to help your students learn the skills necessary to conduct basic land navigation, such that they feel comfortable in an outdoor school, work, or recreational setting. One of the most significant barriers to people feeling comfortable in nature is the fear of getting lost. This program will teach skills to help students feel confident in nature. Appropriate Dress for Your Field Trip To ensure that students get the most out of their FortWhyte experience, we ask that they be appropriately dressed for a 2-hour outdoor excursion. All of our programs include time outdoors, regardless of weather. Comfort and safety are key in making this an enjoyable and memorable experience. PLEASE NOTE: We STRONGLY encourage students to come to this program with a watch, or some other way of telling the correct time. Please try to see that your group is equipped! Suggestions for Outdoor Dress Layering of clothing is very important in maintaining body temperature and in remaining dry. Four thin garments may offer the same degree of warmth as one thick overcoat, but the four layers allow much greater flexibility. Layers can be shed or added as temperature, wind, exertion, or other variables dictate. Waterproof outer layers are also important. Rain may get us wet but so will dew on grass, melting snow on pants and puddles in the spring. Boots in the winter are always important to keep moisture out and heat in. -

2018 Basic Alpine Climbing Course Student Handbook

Mountaineers Basic Alpine Climbing Course 2018 Student Handbook 2018 Basic Alpine Climbing Course Student Handbook Allison Swanson [Basic Course Chair] Cebe Wallace [Meet and Greet, Reunion] Diane Gaddis [SIG Organization] Glenn Eades [Graduation] Jan Abendroth [Field Trips] Jeneca Bowe [Lectures] Jared Bowe [Student Tracking] Jim Nelson [Alpine Fashionista, North Cascades Connoisseur] Liana Robertshaw [Basic Climbs] Vineeth Madhusudanan [Enrollment] Fred Beckey, photograph in High Adventure, by Ira Spring, 1951 In loving memory Fred Page Beckey 1 [January 14, 1923 – October 30, 2017] Mountaineers Basic Alpine Climbing Course 2018 Student Handbook 2018 BASIC ALPINE CLIMBING COURSE STUDENT HANDBOOK COURSE OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................................ 3 Class Meetings ............................................................................................................................ 3 Field Trips ................................................................................................................................... 4 Small Instructional Group (SIG) ................................................................................................. 5 Skills Practice Nights .................................................................................................................. 5 References ................................................................................................................................... 6 Three additional -

An Introduction to Trail Orienteering for Organisers, Planners and Participants

IntrO Paralympic class and Open class competitors at WTOC 2013 in France An introduction to trail orienteering for organisers, planners and participants. Sept 2013 1. Introduction This manual is for organisers, planners and participants unfamiliar with trail orienteering or wishing to refresh their understanding of it. It deals with IntrO, which is the name given to a simplified introductory form of trail orienteering. Those reading this manual are almost certainly familiar with orienteering, as generally practised, and may have some idea about trail orienteering. But there can be misconceptions, so the essential elements of the discipline are re-stated here. Trail orienteering is a world sport FootO MTBO SkiO TrailO TrailO is one of the four disciplines of orienteering, governed by the International Orienteering Federation, based in Helsinki, Finland. All four disciples have annual world championships. TrailO is not yet as widespread as FootO but extends from the USA to Japan (via Europe). Trail orienteering is a sport for all Do not misinterpret the official trailO logo. Although the discipline was specially designed as a non-athletic, intellectual version of orienteering, in order that those in wheelchairs and others with mobility difficulties can take full part in competition, so can the able-bodied. TrailO events are always open to all without regard to age, gender or mobility impairment, but may also have a closed ‘Paralympic’ class, usually on the same course. The popularity of trailO is such that the majority of participants are able-bodied including world champion foot orienteers. It is particularly attractive to those orienteers who, for whatever reason, find foot orienteering becoming too physical but wish to continue participating in orienteering. -

Navigating on Web Maps: Route Characteristics and Performance

Navigating on web maps: Route characteristics and performance Stefan Fuest Rui Li Angela Schwering Institute for Geoinformatics Department of Institute for Geoinformatics University of Muenster Geography and Planning University of Muenster Heisenbergstraße 2 University at Albany, SUNY Heisenbergstraße 2 Muenster, Germany 1400 Washington Ave Muenster, Germany [email protected] Albany, NY, USA [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Providing spatial information by using maps has been developed into a widely accepted means for supporting wayfinding. While most studies focus on the effects of actual wayfinding performance, this study investigates how different route characteristics affect the interactions and wayfinding on online maps. These characteristics are assessed by constructing verbal route descriptions in three different conditions: 1) allocentric, 2) egocentric, and 3) landmark-based. In total 22 participants were randomly assigned to navigate using all three conditions of instructions to find waypoints on routes with the similar complexity and length. Preliminary results reveal that participants with lower spatial abilities took significantly longer time to complete the navigation tasks than those with higher spatial ability. Furthermore, using allocentric route instructions, participants took less time in finding the waypoints than those using landmark-based instructions. Additionally, interactions such as zooming were found associated with the instruction type. In particular, these findings are slightly different from previous studies carried out in actual environment indicating that landmark-based route instructions are most supportive for actual wayfinding and spatial orientation. When using and interacting directly with maps, however, instructions provided through an egocentric or landmark-based frame, require participants to transfer their acquired egocentric frame of reference to an allocentric frame as represented in maps. -

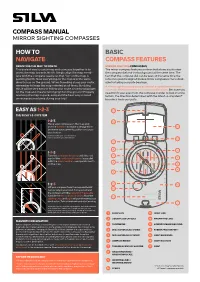

Silva Manual- Mirror Sighting Compasses

COMPASSHOW MANUAL TO MIRROR SIGHTING COMPASSES NAVIGATEHOW TO BASIC NAVIGATE COMPASS FEATURES HOWORIENTING TO THE MAP TO NORTH MIRROR SIGHTING COMPASSES EASYThe easiest way to use a map and compass AS together is to The mirror compass features a mirror that allows you to view orient the map towards North. Simply align the map merid- the compass dial and the background at the same time. The ians with the compass needle so that “up” on the map is fact that the compass dial can be seen at the same time the pointing North. Now everything on the map is in the same reference point is aligned makes mirror compasses more desir- NAVIGATEdirection as on the ground. When travelling along your route, able for taking accurate bearings. remember to keep the map oriented at all times. By doing A mirror-sighting compass is at its best in open terrain where 1-2-3this it will be very easy to follow your route since turning right you must determine direction over long distances. Because you on the map also means turning right on the ground! Properly needn’t lift your eyes from the compass in order to look into the orienting1-2-3 the map is quick, easy1-2 and-3 the best way to avoid1-2- 3 terrain, the direction determined with the Silva 1-2-3 System® HOW TOunnecessaryPlace your compass mistakes on the map duringTurn your the compass trip! housing until the Lift your compass frombecomes the map more accurate. and use the baseline to make a red part of the north/south arrow and hold it horizontally in your EASYstraight line between AS your current is parallel with the map meridians, hand. -

Environmental Geocaching: Learning Through Nature and Technology

WSFNR-20-67A September 2020 ENVIRONMENTAL GEOCACHING: LEARNING THROUGH NATURE AND TECHNOLOGY Brady Self, Associate Extension Professor, Department of Forestry, Mississippi State University Jason Gordon, Assistant Professor, Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia Parents, natural resource professionals and enthusiasts, and youth coordinators often find themselves at a loss when trying to encour- age younger generations to take up outdoor pastimes. The allure of electronic technology, team sports, combined with time availability of parents sometimes limits overall involve- ment of today’s youth in more traditional outdoor activities. In this fast-paced world, learning about nature and what occurs in the forest seems to be losing ground when competing for adolescents’ interest and time. The good news is that there are still many op- portunities to involve youth in the outdoors. The game of geocaching provides one of these opportunities. Geocaching offers learning and fun while spending time in nature. Geocaching is an outdoor treasure hunting game that operates much like the scavenger hunting that many parents and grandparents remember from their youth. The game adds the use of GPS technology (either a dedi- cated receiver unit, or more commonly, a GPS-enabled smartphone) to guide players to locations where individual geocaches are hidden. Clues are then used to search for the geocache. Geocaches can be selected or created with a theme focused on learning about forests, wildlife, and other natural resources. These experiences are then shared online in the geocaching community. The overall objective of the activity is to guide participants to places of significance where they have the opportu- nity to learn something about that particular location or geocache topic. -

Orienteering at Brighton Woods

ORIENTEERING AT BRIGHTON WOODS • There are eight numbered posts (controls) for the orienteering course at Brighton Woods. Each has a number that corresponds to the number on the Brighton Woods Orienteering Map, but they may be found in any order. • It is easier to go directly from control to control when there is less ground cover: late fall, winter, and early spring. Long pants are recommended because of the poison ivy and ticks. 1. NUMBERED CONTROL DESCRIPTIONS 1. Sports Field 2. Southwest End of Pipeline Clearing 3. Amphitheater 4. The Bridge 5. Head of Trail 6. Rock Outcropping 7. River 8. Northeast End of Pipeline Clearing 2. PLOTTING THE COURSE • Find control #1 on the map.(The Sports Field.) • On the map, line up one edge of the compass from where you are (Control #1: Sports Field) to where you want to go, (Control # 2: Southwest End of Pipeline Clearing) making sure the direction-of-travel arrow faces your destination point. (This is the first secret of orienteering.) • Rotate the housing of the compassso that the gridlines are parallel to the North - South gridlines on the orienteering map. The cardinal point N must be at the North side of your map. (This is the second secret to orienteering.) • Readyour bearing in degrees at the Bearing Index. (At the Direction-of- Travel line, or the "Read Bearing Here" mark.) The number of degrees is * • Do not rotate the housing again until you need a new bearing! 3. FINDING THE FIXED CONTROLS • Stand directly in front of the control #1 and hold your compass level and squarely in front of your body. -

INTERNATIONAL ROGAINING FEDERATION Inc. A0040409P ~1976-2006 30 Years of ROGAINING~

INTERNATIONAL ROGAINING FEDERATION Inc. A0040409P ~1976-2006 30 years of ROGAINING~ Box 3, Central Park, 3145 Australia Newsletter No. 128 www.rogaining.com March 2007 IRF Team annual twenty-four hour event and this was to prove the first of a long line of achievements over the next decade. President: Neil Phillips With remarkable diversity, the crew and its members World Rogaining Championships Manager: Peter Taylor pioneered the introduction of females into the scouting Promotions and Development: Brad Hunt movement in Victoria, set up a rock climbing club that Secretary/Treasurer: Rod Phillips Technical Manager: vacant taught climbing leaders from all over Victoria, opened up several new climbing areas, provided leaders for a Czech Republic: Miroslav Seidl, Jan Tojnar number of scout troops and rover crews, went on regular Finland: Iiro Kakko caving and canoeing expeditions, organized hiking, New Zealand: Pete Squires rafting, climbing, flying and camping trips all over Canada: Murray Foubister south-eastern Australia and founded the world’s first United States of America: Brad Hunt, Bob Reddick, rogaining association. The authors of this book were Eric Smith fortunate to share many of the experiences that STR Australia: Rod Phillips, Neil Phillips, Peter Taylor provided. Observer status At the first Surrey Thomas Rovers twenty-four Brazil: José Nilton Silva Vargas hour hike in 1972, forty starters, mostly from scouting, Canada: Francis Falardeau, Alan Stradeski set off from Gembrook, Victoria, and circled the hash Estonia: Andres Käär house at Basan’s Corner via a series of loops along forest Germany: Marko Rößler roads. True cross-country navigation was minimal, but Hong Kong: Patrick Ng the publicity from the event and the emphasis placed on Ireland: Sean Hassett quality hash house service and a friendly atmosphere Israel: Dan Chissick paved the way for similar events over the next two years Japan: Kazuhiro Takashima at Labertouche and Kinglake.