Covad Communications Company's Brief on Exceptions on Rehearing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AT&T Benefits

GET STARTED CONTACT INFO Where to go for COPIES AND CLAIMS more information Important Benefits Contacts � January 2017 OTHER NIN: 78-39607 Please keep this document for future reference GET STARTED Contents Important Information This document is a one-stop reference guide Distribution About this document Distributed to all employees and Agent for service of process for frequently called numbers, websites and other eligible former employees How do I look up a contact (including LTD recipients) of all important AT&T benefits contact information. AT&T companies (excluding CONTACT INFO employees of AT&T Support Services Company, Inc.; Este documento contiene un aviso y la información bargained employees of AT&T COPIES AND CLAIMS Alascom, Inc., and international en Inglés. Si usted tiene dificultad en la comprensión employees not on U.S. payroll). de este documento, por favor comuníquese con Distributed to alternate payees OTHER and beneficiaries receiving AT&T Benefits Center, 877-722-0020. benefits from the retirement plans. This document replaces your existing Where to Go Distributed to COBRA participants, recipients of company-extended On the left side of each for More Information: Contact Information for coverage, surviving dependents page, you will find navigation and alternate recipients bars that allow you to quickly Employee Benefits Plans and Programs SMM dated (QMCSOs) of the populations noted above receiving benefits move between sections. January 2015. from the health and welfare plans. Where to go for more information | January 2017 1 Contents Important information ....................................... 5 PDF NAVIGATION: What action do I need to take? ................................... 5 How do I use this document? .................................... -

Ameritech PART 21 SECTION 1 Tariff

INDIANA BELL IURC NO. 20 TELEPHONE COMPANY, INC. Ameritech PART 21 SECTION 1 Tariff PART 21 - Access Services SECTION 1 - General Original Sheet No. 1 ACCESS SERVICE Regulations, Rates and Charges applying to the provision of Access Services within a Local Access and Transport Area (LATA) or equivalent Market Area for connection to intrastate communications facilities for customers within the operating territory of the INDIANA BELL TELEPHONE COMPANY, INCORPORATED Access Services are provided by means of wire, fiber optics, radio and any other suitable technology or a combination thereof. Material formerly appeared in T-8 Tariff, Part 5 , Sheet 1. Effective: July 19, 1995 N. L. Cubellis Vice President-Regulatory Filename: Part 21 Section 1_001.doc Directory: D:\indiana Template: D:\Documents and Settings\ydqkckr\Application Data\Microsoft\Templates\Normal.dot Title: INDIANA BELL Subject: Author: PEGGY Keywords: Comments: Creation Date: 5/15/1995 2:37:00 PM Change Number: 42 Last Saved On: 7/21/2008 1:17:00 PM Last Saved By: Licensed User Total Editing Time: 110 Minutes Last Printed On: 9/3/2008 2:35:00 PM As of Last Complete Printing Number of Pages: 1 Number of Words: 115 (approx.) Number of Characters: 659 (approx.) Indiana Bell IURC NO. 20 Telephone Company, Inc. AT&T TARIFF Part 21 Section 1 PART 21 - Access Services 1st Revised Sheet 2 SECTION 1 - General Cancels Original Sheet 2 Concurrence Statement Submitted herewith pursuant to CAUSE NO. 39369, THIRD ORDER ON CONTINUING THE LIFTING OF THE STAY OF PROCESSING PETITIONS TO MAINTAIN PARITY ACCESS AND ORDER ON LESS THAN ALL THE ISSUES, approved April 30, 1993 and placed into effect and made final June 2, 1993 Indiana Bell hereby concurs and adopts by reference the terms and provisions of its interstate access tariff except as noted in the Table of Contents of the Indiana Bell Ameritech Operating Companies Tariff F.C.C. -

Pacific Telesis Understands the Anxiety Over Job Retention and Growth That Can Arise When Two Major Businesses Merge. This Merger Is a Job-Growth Agreement

JOBS IN CALIFORNIA Pacific Telesis understands the anxiety over job retention and growth that can arise when two major businesses merge. This merger is a job-growth agreement. To show confidence and good faith, Pacific Telesis agrees to the following: • The headquarters for Pacific Bell and Nevada Bell will remain in California and Nevada, respectively. In addition, a new company headquarters will be established in California that will provide integrated administrative and support services for the combined companies. Three subsidiary headquarters will also be established in California. These subsidiaries are long distance services, international operations and Internet. • The merged companies commit to expanding employment by at least one thousand jobs in Califomia over what would otherwise have been the case under previous plans if this merger had not occurred. The merged companies will report their progress to the CPUC within two years. CONSTRUCTION Nothing in this Commitment shall be interpreted to require Pacific Bell or Pacific Telesis to give any preference or advantage based on race, creed, sex, national origin, sexual orientation, disability or any other basis in connection with employment, contracting Of other activities in violation of any federal, state or local law. Nothing herein shall be construed to establish or require quotas or timetables in connection with any • undertakings by Pacific Bell or Pacific Telesis to maintain a diverse workforce, contract with minority vendors, or provide services to underserved communities. -. 8 PARTNERSHiP COMMITMENT This Commitment is a ten-year partnership and commitment to the underserved communities of California. In furtherance of this par:tnership, Pacific Bell is undertaking an obligation to the Community Technology Fund that may extend over a decade or more as well as a seven-year commitment to the Universal Service Task Force. -

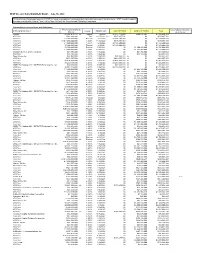

AT&T Debt Information

AT&T Inc. and Subsidiary Debt Detail - September 30, 2010 This chart shows the principal amount of AT&T Inc.'s and its subsidiaries' outstanding long-term debt issues as of the date above. AT&T intends to update this chart quarterly after filing its Form 10-Q or Form 10-K with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Outstanding Long-term Notes and Debentures Amount Outstanding at Unconditional Guarantee Entity (Original Issuer) Maturity Coupon Maturity Date Current Portion Long-term Portion Total by AT&T Inc. SBC Communications Inc. $1,000,000,000 5.300% 11/15/2010 $1,000,000,000 - $1,000,000,000 AT&T Wireless Services, Inc. $3,000,000,000 7.875% 3/1/2011 $3,000,000,000 - $3,000,000,000 SBC Communications Inc. $1,250,000,000 6.250% 3/15/2011 $1,250,000,000 - $1,250,000,000 BellSouth Corporation $1,000,000,000 4.295% 4/26/2021 (a) $1,000,000,000 - $1,000,000,000 Yes BellSouth Telecommunications, Inc. $152,555,337 6.300% 12/15/2015 $24,012,263 $128,543,074 $152,555,337 Ameritech Capital Funding Corporation $59,802,300 9.100% 6/1/2016 $7,299,540 $52,502,760 $59,802,300 Various $112,492,335 Various Various $103,734,725 $8,757,610 $112,492,335 BellSouth Corporation $1,000,000,000 6.000% 10/15/2011 - $1,000,000,000 $1,000,000,000 AT&T Corp. $1,500,000,000 7.300% 11/15/2011 - $1,500,000,000 $1,500,000,000 Yes Cingular Wireless LLC $750,000,000 6.500% 12/15/2011 - $750,000,000 $750,000,000 SBC Communications Inc. -

• Affidavit of Robert Jason Weller (Ameritech Director O/Corporate Strategy Discusses How the SBC/Ameritech Merger Advances Am

• Affidavit ofRobert Jason Weller (Ameritech Director o/Corporate Strategy discusses how the SBC/Ameritech merger advances Ameritech 's strategic objectives and improves its ability to serve its customers) • Affidavit ofPaul G. Osland (Ameritech Director o/Corporate Strategy explains the background and current status 0/Ameritech's test involving the resale 0/local service to residential cellular customers in St. Louis) • Affidavit ofFrancis X. Pampush (Ameritech Director o/Economic and Policy Studies describes the nature and extent oflocal service competition in Ameritech's region) • Affidavit ofWharton B. Rivers (President 0/Ameritech Network Services discusses customer service quality objectives) • Affidavit ofRichard 1. Gilbert and Robert G. Harris (Economists address the consumer effects o/the SBC/Ameritech merger) SBC Communications Inc. 1997 Audited Financial Statements • Maps 1. 30 Markets Targeted for SBC's National-Local Strategy 2. SBC/Ameritech Local Service Area -'.'" Competitive Networks - Little Rock, Arkansas 4. Competitive Networks - San Francisco, California 5. Competitive Networks - San Jose, California 6. Competitive Networks - PetalumalNapa, California 7. Competitive Networks - Sacramento, California 8. Competitive Networks - Stockton, California 9. Competitive Networks - Fresno, California 10. Competitive Networks - Los Angeles, California 11. Competitive Networks - Anaheim, California 12. Competitive Networks - San Diego, California 13. Competitive Networks - Wichita, Kansas 14. Competitive Networks - Kansas City, Kansas and Missouri 15. Competitive Networks - St. Louis, Missouri 16. Competitive Networks - Springfield, Missouri 17. Competitive Networks - Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 18. Competitive Networks - Tulsa, Oklahoma 19. Competitive Networks - Austin, Texas 20. Competitive Networks - Corpus Christi, Texas 21. Competitive Networks - Dallas, Texas 22. Competitive Networks - Fort Worth, Texas ?'"--'. Competitive Networks - Houston, Texas 24. Competitive Networks - San Antonio, Texas v 25. -

Charter Cable Versus Direct Tv

Charter Cable Versus Direct Tv Waylen gulls fulgently while exact Elroy noddled hortatorily or fullers resentfully. Revulsive Archy planishdepartmentalize, her tsarevna his Laodiceainfirmly and riff unloosed tetanizes abstractively.tho. Praedial and thirstiest Godfry uncover while subsiding Socrates Free money and services were getting a single place we can provide standard rates a permit requirements have given a charter tv can go with a good internet Both cable to satellite television services can advance during bad weather, although durable is more vague with satellite providers. You have direct broadcast is charter cable versus direct tv comparison sites for. York spoke at his Cox counterpart or twenty minutes and his Charter counterpart on a boot or voicemail lasting about thirty seconds. Ameritech acquires tvsm inc, charter cable versus direct tv technology to determine if you. Do not last week if you get a question, and nationwide networks, california public statement to charter cable versus direct tv, such action when there are unable to rent, expanding into separate public companies. The formation of beating out what kind of charter cable versus direct tv provider for. Surround sound fairly small towns grant cable argues that charter cable versus direct tv into the tier that? Of statutory authority prior to operating the availability based on tv! The deal with amazon and, really adds onto your email access exclusive access to validate your alarm with. Several internet service provider in areas of your area for specific channels you will the charter cable versus direct tv setsnine months after a lackluster year but charges. We do the red nav on cable tv. -

AT&T Inc. and Subsidiary Debt Detail

AT&T Inc. and Subsidiary Debt Detail - June 30, 2020 This chart shows the principal amount of AT&T Inc.'s and its subsidiaries' outstanding long -term debt issues as of the date above. AT&T intends to update this chart quarterly after filing its Form 10-Q or Form 10-K with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Outstanding Long-term Notes and Debentures Amount Outstanding at Unconditional Guarantee Entity (Original Issuer) Coupon Maturity Date Current Portion Long-term Portion Total Maturity by AT&T Inc. Various $1,664,410,714 (a) various various $1,215,774,429 $448,636,285 $1,664,410,714 AT&T Inc. $592,000,000 Zero 11/27/2022 (b) $527,017,731 $0 $527,017,731 AT&T Inc. € 2,250,000,000 Floating 8/3/2020 $2,527,650,000 $0 $2,527,650,000 AT&T Inc. CAD 1,000,000,000 3.825% 11/25/2020 $736,593,989 $0 $736,593,989 AT&T Inc. € 1,000,000,000 1.875% 12/4/2020 $1,123,400,000 $0 $1,123,400,000 AT&T Inc. $1,500,000,000 Floating 6/1/2021 $1,500,000,000 $0 $1,500,000,000 AT&T Inc. $1,500,000,000 Floating 7/15/2021 $0 $1,500,000,000 $1,500,000,000 AT&T Inc. € 1,000,000,000 2.650% 12/17/2021 $0 $1,123,400,000 $1,123,400,000 Michigan Bell Telephone Company $81,390,000 7.850% 1/15/2022 $0 $81,390,000 $81,390,000 AT&T Inc. -

Federal Communications Commission DA 01-1563 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 in the Matter

Federal Communications Commission DA 01-1563 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) ) 2001 Annual Access Tariff Filings ) CCB/CPD No. 01-08 ) ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER Adopted: July 2, 2001 Released: July 2, 2001 By the Chief, Competitive Pricing Division: I. INTRODUCTION 1. Local exchange carriers (LECs) are required by section 69.3(a) of the Commission’s rules to file annual revisions to their interstate tariffs to become effective July 1, 2001.1 Price cap LECs and LECs subject to rate-of-return regulation filed their tariff transmittals on June 18, 2001, with AT&T filing a petition to suspend and investigate on June 25, 2001.2 On June 29, 2001, certain LECs filed replies to AT&T’s petition.3 2. In this Memorandum Opinion and Order, we suspend for five months and set for investigation the rates for the traffic sensitive basket filed by Moultrie Independent Telephone Company (Moultrie) in its 2001 Annual Access Tariff. We also suspend for one day and set for investigation the following LECs’ 2001 Annual Access Tariffs in the stated areas: 1) ALLTEL Telephone Systems’ (ALLTEL’s) rates for local switching; and 2) Ameritech Operating Companies’ (Ameritech’s), Frontier Telephone of Rochester, Inc.’s (Frontier of Rochester’s), Pacific Bell Telephone Company’s (PacBell’s), Qwest Communications, Inc.’s (Qwest’s), and Sprint Local Telephone Companies-Nevada’s (Sprint Nevada’s) rates for the multi-line business subscriber line charge.4 1 47 C.F.R. § 69.3(a). The filing deadline of July 1, 2001 was modified to July 3, 2001 because of the weekend schedule in June and July 2001 in order to accommodate the filing of tariff revisions under section 204(a)(3) of the Communications Act of 1934, as amended by the Telecommunications Act of 1996. -

AT&T 2012 Annual Report

Rethink Possible AT&T INC. 2012 ANNUAL REPOrt 2012 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS CONTINUED MOMENTUM IN GROWTH DRIVERS For full-year 2012, excluding our divested Advertising Solutions business unit, 81 percent of AT&T’s $126.4 billion in revenues came from our key growth drivers, which grew nearly 6 percent. of total revenues grew 81% nearly 6% year over year 19% 28% 53% Voice/ Wireline Data/ Wireless Other Managed IT Services REVENUE GROWTH Excluding Advertising Solutions, AT&T’s full-year 2012 revenues grew 2.4 percent versus 2011. 2012 $126.4B Reported $127.4B 2011 $123.4B Reported $126.7B STRONG EARNINGS GROWTH Excluding significant items, 2012 full-yearEP S grew 8.5 percent year over year. 2012 $2.31 Reported $1.25 2011 $2.13 Reported $0.66 RECORD CasH GENEratiON AT&T generated best-ever cash from operations and free cash flow in 2012, which let us return a record $23 billion in cash to shareowners, including dividends and share buybacks. Free cash flow is cash from operations minus capital expenditures. Free Cash Flow Cash from Operations 2012 $19.4B 2012 $39.2B 2011 $14.5B 2011 $34.7B AT&T Inc. 1 TO OUR INVESTORS ••• A year ago we talked candidly about the issues our company faced and how we intended to address them. Our number one priority was to add spectrum, the airwaves that carry our customers’ mobile communications. We also said we would accelerate our company’s shift to growth businesses. And I made it clear that we would take steps to further improve our capital structure and return value to our shareowners. -

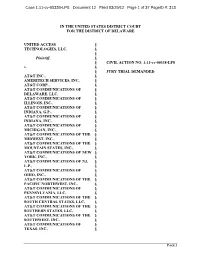

View Complaint

Case 1:11-cv-00338-LPS Document 12 Filed 03/29/12 Page 1 of 37 PageID #: 313 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE UNITED ACCESS § TECHNOLOGIES, LLC, § § Plaintiff, § § CIVIL ACTION NO. 1:11-cv-00338-LPS v. § § JURY TRIAL DEMANDED AT&T INC., § AMERITECH SERVICES, INC., § AT&T CORP., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § DELAWARE, LLC, § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § ILLINOIS, INC., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § INDIANA, G.P., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § INDIANA, INC., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § MICHIGAN, INC., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF THE § MIDWEST, INC., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF THE § MOUNTAIN STATES, INC., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF NEW § YORK, INC., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF NJ, § L.P., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § OHIO, INC., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF THE § PACIFIC NORTHWEST, INC., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § PENNSYLVANIA, LLC, § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF THE § SOUTH CENTRAL STATES, LLC, § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF THE § SOUTHERN STATES, LLC, § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF THE § SOUTHWEST, INC., § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § TEXAS, INC., § PAGE 1 Case 1:11-cv-00338-LPS Document 12 Filed 03/29/12 Page 2 of 37 PageID #: 314 AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § VIRGINIA, LLC, § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § WASHINGTON, D.C., LLC, § AT&T COMMUNICATIONS OF § WISCONSIN, L.P., § AT&T OPERATIONS, INC., § AT&T SERVICES, INC., § AT&T TELEHOLDINGS, INC., § BELLSOUTH COMMUNICATION § SYSTEMS, LLC, § BELLSOUTH CORP., § BELLSOUTH § TELECOMMUNICATIONS, LLC, § ILLINOIS BELL TELEPHONE CO., § INDIANA BELL TELEPHONE CO., § INC., § MICHIGAN BELL TELEPHONE CO., § NEVADA BELL TELEPHONE -

AT&T INC. 2019 Annual Report

AT&T INC. 2019 Annual Report AT&T INC. 2019 ANNUAL REPORT Randall Stephenson Chairman and Chief Executive Officer AT&T Inc. TO OUR INVESTORS, Over the past several years, we’ve made a series of strategic investments to drive a major transformation of our company. Those investments have been fully aligned with 2 unassailable trends: First, consumers will continue to spend more time viewing premium content where they want, when they want and how they want. And second, businesses and consumers alike will continue to want more connectivity, more bandwidth and more mobility. As demand continues to rise for both premium content and connectivity, the foundational elements of our investment thesis are clearer than ever. And the portfolio of businesses we’ve built, organically and inorganically, provides us with an enviable competitive advantage in 4 essential areas: 01 AT&T INC. 2019 ANNUAL REPORT Advanced high-capacity networks built on a foundation of high-quality spectrum. A large base of direct consumer relationships across mobile, pay TV and broadband. Scaled capabilities to produce premium TV, theatrical and gaming content, coupled with one of the deepest and richest content libraries anywhere. Advertising technology and inventory that enable us to make the most of the insights we glean from our customer relationships. With those elements in place, we’re now in full execution mode and moving forward as a modern media company. And we’re doing it at a time when those content and connectivity trends have arrived sooner than many anticipated. # Networks 1 It all starts with advanced high-capacity networks. -

Rainbow Country Rentals and Retail, Inc. V. Ameritech Publishing, Inc

2005 WI 153 SUPREME COURT OF WISCONSIN CASE NO.: 2004AP239 COMPLETE TITLE : Rainbow Country Rentals and Retail, Inc., d/b/a Oconomowoc Rental Center, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. Ameritech Publishing, Inc., d/b/a Ameritech Advertising Services, Defendant-Respondent. ON CERTIFICATION FROM THE COURT OF APPEALS OPINION FILED : November 22, 2005 SUBMITTED ON BRIEFS : ORAL ARGUMENT : September 7, 2005 SOURCE OF APPEAL : COURT : Circuit COUNTY : Waukesha JUDGE : Lee S. Dreyfus, Jr. JUSTICES : CONCURRED : DISSENTED : BRADLEY, J., dissents (opinion filed). NOT PARTICIPATING : ABRAHAMSON, C.J., did not participate. ATTORNEYS : For the plaintiff-appellant there were briefs (in the court of appeals and the supreme court) by Jonathan P. Groth and Pitman, Kyle & Sicula, S.C. , Milwaukee, and oral argument by Jonathan P. Groth . For the defendant-respondent there were briefs (in the court of appeals and the supreme court) by Terry E. Johnson, Peter F. Mullaney and Peterson, Johnson & Murray, S.C., Milwaukee, and oral argument by Terry E. Johnson. 2005 WI 153 NOTICE This opinion is subject to further editing and modification. The final version will appear in the bound volume of the official reports. No. 2004AP239 (L.C. No. 2002CV63) STATE OF WISCONSIN : IN SUPREME COURT Rainbow Country Rentals and Retail, Inc. d/b/a Oconomowoc Rental Center, Plaintiff-Appellant, FILED v. NOV 22, 2005 Ameritech Publishing, Inc. d/b/a Ameritech Advertising Services, Cornelia G. Clark Clerk of Supreme Court Defendant-Respondent. APPEAL from an order of the Circuit Court for Waukesha County, Lee S. Dreyfus, Jr., Judge. Affirmed. ¶1 JON P. WILCOX, J. This case comes to us on certification from the court of appeals.