Northwestern University “Mise En Vie” and Intra-Culturalism: Performing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Donatella Feat. Rettore

DONATELLA FEAT. RETTORE: Giovedì 25 giugno 2015 – ore 00.00 GAY VILLAGE 2015 Dal 18 giugno al 12 settembre 2015 Ingresso gratuito dalle 19.00 alle 21.00 Roma Eur - Parco del Ninfeo - Via delle Tre Fontane www.gayvillage.it 22/06/2015 Giovedì 25 giugno 2015 – ore 00.00 Dopo la vittoria de L'Isola dei Famosi Le DONATELLA dedicano a tutti i fan e al pubblico Gay Village DONATELLA FEAT. RETTORE produced and arranged by Tommy Vee, Mauro Ferrucci, Keller & Crossfingers supervised and realized by Mattia Guerra for Agidi srl IN TUTTI I DIGITAL STORE E DOPO IL SINGOLO ARRIVA LA DONADANCE: Chissà come sarebbe andata se fossero rimaste le Provs Destination. Non lo sapremo mai perché nella sesta edizione del talent show X Factor, l'allora giudice Arisa aveva intuito che le giovanissime sorelle gemelle Giulia e Silvia Provvedi avevano non solo un innato talento per il mondo dello spettacolo, ma anche un punto di riferimento nel firmamento musicale italiano: Donatella Rettore. Da quel momento le allora 18enni modenesi divennero le Donatella. Vincitrici dell'ultima trionfale edizione de L'Isola dei Famosi, le Donatella si lanciano con il loro incontenibile entusiasmo in questo nuovo progetto, il brano Donatella: "Non lo vediamo come un singolo vero e proprio ma come un divertimento in musica, un regalo a tutti i nostri fan in perfetto stile Donatella: energico, pieno di vita e travolgente!" Con questa scelta vogliono naturalmente rendere omaggio alla regina del synth pop anni '80 che ha ispirato il loro nome d'arte: Donatella Rettore. "Per noi si realizza un sogno -? dichiarano: abbiamo sempre desiderato conoscere Donatella Rettore e finalmente ce l'abbiamo fatta! Questo progetto ci riempie di orgoglio: una rivisitazione moderna in chiave dance del famoso brano del 1981, che abbiamo sempre amato moltissimo per la sua ironia e sregolatezza. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Calendrical Calculations: the Millennium Edition Edward M

Errata and Notes for Calendrical Calculations: The Millennium Edition Edward M. Reingold and Nachum Dershowitz Cambridge University Press, 2001 4:45pm, December 7, 2006 Do I contradict myself ? Very well then I contradict myself. (I am large, I contain multitudes.) —Walt Whitman: Song of Myself All those complaints that they mutter about. are on account of many places I have corrected. The Creator knows that in most cases I was misled by following. others whom I will spare the embarrassment of mention. But even were I at fault, I do not claim that I reached my ultimate perfection from the outset, nor that I never erred. Just the opposite, I always retract anything the contrary of which becomes clear to me, whether in my writings or my nature. —Maimonides: Letter to his student Joseph ben Yehuda (circa 1190), Iggerot HaRambam, I. Shilat, Maaliyot, Maaleh Adumim, 1987, volume 1, page 295 [in Judeo-Arabic] If you find errors not given below or can suggest improvements to the book, please send us the details (email to [email protected] or hard copy to Edward M. Reingold, Department of Computer Science, Illinois Institute of Technology, 10 West 31st Street, Suite 236, Chicago, IL 60616-3729 U.S.A.). If you have occasion to refer to errors below in corresponding with the authors, please refer to the item by page and line numbers in the book, not by item number. Unless otherwise indicated, line counts used in describing the errata are positive counting down from the first line of text on the page, excluding the header, and negative counting up from the last line of text on the page including footnote lines. -

1614598183048 Newsrai

SANREMO “70 + 1” Il Festival 2021, ancora più musica Musica, sempre di più. E con tutte le sfumature proposte dai 26 Campioni in gara, ai quali si aggiungo- no le 8 Nuove Proposte. Il 71° Festival di Sanremo (anzi, il “70 + 1”) firmato dal Direttore Artistico Ama- deus va in scena: cinque appuntamenti, dal 2 al 6 marzo in prima serata su Rai1, Radio2 e RaiPlay, in diretta da un Teatro Ariston completamente trasformato dalla scenografia di Gaetano e Chiara Ca- stelli, mentre la regia – tra tradizione e sperimentazione - è firmata da Stefano Vicario. Ad affiancare Amadeus sul palco dell’Ariston, ci saranno Fiorello, Zlatan Ibrahimovic, Achille Lauro, Matilda De An- gelis, Elodie, Vittoria Ceretti, Barbara Palombelli e altri grandi ospiti dal mondo della musica e non solo. Come sempre, i cantanti saranno accompagnati dall’Orchestra del Festival - composta da musicisti professionisti in parte scelti dalla Rai e in parte messi a disposizione dalla Fondazione Orchestra Sin- fonica di Sanremo – e dai coristi. “Io, Fiorello e tutte le persone che lavorano con noi – dice Amadeus - siamo sicuri che sarà un San- remo da ricordare, in un anno tra i più difficili della nostra vita, con la voglia di ripartire e di regalare al pubblico a casa qualcosa di unico. Il Festival di Sanremo ci appartiene, appartiene al costume e alla musica di questo Paese. Anche tra mille difficoltà: ‘La musica non si ferma mai‘. Lo spettacolo sta per iniziare!”. I 26 Campioni parteciperanno ciascuno con una canzone inedita e si esibiranno a gruppi di 13 nella prima e nella seconda serata del Festival. -

A/W/Visual A/W 4

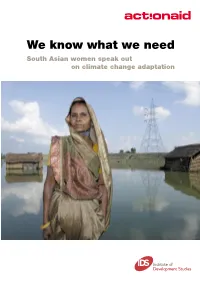

We know what we need South Asian women speak out on climate change adaptation Acknowledgements This report was written by Tom Mitchell, Thomas Tanner and Kattie Lussier (Institute of Development Studies (IDS) at the University of Sussex, UK). Many thanks are due to numerous people who helped with field work, advised on the analysis or commented on drafts, including: Bangladesh: Wahida Bashar Ahmed, Naureen Fatema, Ferhana Ferdous and ActionAid Bangladesh team India: Neha Aishwarya, , Sharad Kumari, Mona, Raman Mehta and Jyoti Prasad and ActionAid India team Nepal: Ambika Amatya, Dhruba Gautam, Rajesh Hamal, Shyam Jnavaly, Amrita Sharma and ActionAid Nepal team Ennie Chipembere, Tony Durham, Sarah Gillam, Anne Jellema, Marion Khamis, Akanksha Marphatia, Yasmin McDonnell, Colm O’Cuanachain, Shashanka Saadi, Ilana Solomon, Tom Sharman, Harjeet Singh, Annie Street and Roger Yates Khurshid Alam (consultant) Most importantly, special thanks go to This report was edited by Angela Burton, Marion Khamis the many women who contributed and and Stephanie Ross and designed by Sandra Clarke. participated in the research from the Photographers: Pabna and Faridpur districts in Bangladesh, Bangladesh: Emdadul Islam Bitu the Muzaffarpur district in India and India: Sanjit Das the Banke and Bardiya districts in Nepal. Nepal: Binod Timilsena Front cover photograph: Sanjit Das / ActionAid November 2007 Contents Executive summary 4 1 Introduction 6 2 The rationale: women and climate change adaptation in the Ganga river basin 10 3 The evidence: women’s livelihood adaptation priorities 14 4 The policy gap: women’s rights in adaptation financing 17 5 The lessons: recommendations for adaptation finance 20 Notes 22 Sanjit Das / ActionAid page 3 Executive summary I am 60 years old and I have never experienced so much flooding, droughts, hot winds and hailstones as in recent years… “I am surprised how often we have these problems. -

Baby Girl Names Registered in 2018

Page 1 of 46 Baby Girl Names Registered in 2018 Frequency Name Frequency Name Frequency Name 8 Aadhya 1 Aayza 1 Adalaide 1 Aadi 1 Abaani 2 Adalee 1 Aaeesha 1 Abagale 1 Adaleia 1 Aafiyah 1 Abaigeal 1 Adaleigh 4 Aahana 1 Abayoo 1 Adalia 1 Aahna 2 Abbey 13 Adaline 1 Aaila 4 Abbie 1 Adallynn 3 Aaima 1 Abbigail 22 Adalyn 3 Aaira 17 Abby 1 Adalynd 1 Aaiza 1 Abbyanna 1 Adalyne 1 Aaliah 1 Abegail 19 Adalynn 1 Aalina 1 Abelaket 1 Adalynne 33 Aaliyah 2 Abella 1 Adan 1 Aaliyah-Jade 2 Abi 1 Adan-Rehman 1 Aalizah 1 Abiageal 1 Adara 1 Aalyiah 1 Abiela 3 Addalyn 1 Aamber 153 Abigail 2 Addalynn 1 Aamilah 1 Abigaille 1 Addalynne 1 Aamina 1 Abigail-Yonas 1 Addeline 1 Aaminah 3 Abigale 2 Addelynn 1 Aanvi 1 Abigayle 3 Addilyn 2 Aanya 1 Abiha 1 Addilynn 1 Aara 1 Abilene 66 Addison 1 Aaradhya 1 Abisha 3 Addisyn 1 Aaral 1 Abisola 1 Addy 1 Aaralyn 1 Abla 9 Addyson 1 Aaralynn 1 Abraj 1 Addyzen-Jerynne 1 Aarao 1 Abree 1 Adea 2 Aaravi 1 Abrianna 1 Adedoyin 1 Aarcy 4 Abrielle 1 Adela 2 Aaria 1 Abrienne 25 Adelaide 2 Aariah 1 Abril 1 Adelaya 1 Aarinya 1 Abrish 5 Adele 1 Aarmi 2 Absalat 1 Adeleine 2 Aarna 1 Abuk 1 Adelena 1 Aarnavi 1 Abyan 2 Adelin 1 Aaro 1 Acacia 5 Adelina 1 Aarohi 1 Acadia 35 Adeline 1 Aarshi 1 Acelee 1 Adéline 2 Aarushi 1 Acelyn 1 Adelita 1 Aarvi 2 Acelynn 1 Adeljine 8 Aarya 1 Aceshana 1 Adelle 2 Aaryahi 1 Achai 21 Adelyn 1 Aashvi 1 Achan 2 Adelyne 1 Aasiyah 1 Achankeng 12 Adelynn 1 Aavani 1 Achel 1 Aderinsola 1 Aaverie 1 Achok 1 Adetoni 4 Aavya 1 Achol 1 Adeyomola 1 Aayana 16 Ada 1 Adhel 2 Aayat 1 Adah 1 Adhvaytha 1 Aayath 1 Adahlia 1 Adilee 1 -

Bengali English Calendar 2018 Pdf

Bengali english calendar 2018 pdf Continue Bengali Calendar 1425 (Eng: 2018-2019) Baisakh- 13/14. Joystha -10/18. Jordi. Sharaban - 13.Vadra - 4/14. Aswin - 3. Kartik -1/2/4/9/12. Agrahan - 11/14. Wells -1/8/11 . Magh - 1/4. Falgun -9/12. Chaitra - 1. USK: All agesBengali Calendar PanjikaBengali Calendar is also known as the Bangla Calendar or Bong Calendar. The current Bengali year is the Bengali calendar 1425 BS or Bengali Sambat. The Bengali calendar is based on the solar calendar. There are two types of Bengali calendar. One is used as an offical calendar in Bangladesh (BD) and another used in the Indian states (IN) of West Bengal (WB), Tripura and Assam. * - Easy scrolling view* - Vertical view* - Updated by Bengali Year ১৪২৫ (1425)* - Bengal calendar 2018* - best calendar application* - calendar application 2018* - 2019 calendar application* - Bengal calendar 2018* - Bengali calendar 2018bengali calendar 1425bengalicalendar1425bengali panjikabengali panjika 2018bengali panjika marriage datesbang English calendar today and calendar appsbangla datebengali calendar new year calendar bengali calendar online bangladesh calendar bangladesh calendars bangladesh calendarbengali and english calendarbengali full panjikapanjikaBangla date of marriage Date MarchNew Bangladesh panjika2018 Bangladesh panjikaBangla panjika 2018 West Bengal Festivals 321 Contains Ads Calendar Bangla 2019 application is useful for people from West Bengal and Bengali speaking to people all over the world. This application intends to bring you information about Calendar -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Festival Di Sanremo 2021, La Classifica Generale Dopo I Duetti E Le Cover

1 Festival di Sanremo 2021, la classifica generale dopo i duetti e le cover della terza serata di Giulia Novello – 05 Marzo 2021 – 8:36 Sanremo. Sono stati i musicisti dell’orchestra del 71° Festival di Sanremo a decretare la classifica dei Big dopo la terza serata della kermesse, dedicata a cover e duetti. Si riconferma primo Ermal Meta, già sul gradino più alto del podio per la giuria demoscopica con la sua “Un milione di cose da dirti“. Ecco la classifica completa della terza serata: 1. Ermal Meta – “Caruso” (Lucio Dalla) con Napoli Mandolin Orchestra 2. Orietta Berti – “Io che amo solo te” (Sergio Endrigo) con Le Deva 3. Extraliscio feat. Davide Toffolo – Medley “Rosamunda” (Gabriella Ferri) con Peter Pichler 4. Willie Peyote – “Giudizi universali” (Samuele Bersani) con Samuele Bersani 5. Arisa – “Quando” (Pino Daniele) con Michele Bravi 6. Maneskin – “Amandoti” (Cccp Di Giovanni Lindo Ferretti) con Manuel Agnelli 7. Annalisa – “La musica è finita” (Ornella Vanoni) con Federico Poggipollini 8. Max Gazzè – “Del mondo” (Csi Di Giovanni Lindo Ferretti) con Daniele Silvestri e The Magical Mistery Band 9. La Rappresentante di Lista – “Splendido splendente” (Donatella Rettore) con Donatella Rettore 10. Ghemon – Medley “Le ragazze”, “Donne”, “Acqua e sapone”, “La canzone del sole” con i Neri Per Caso 11. Lo Stato Sociale – “Non è per sempre” (Afterhours) con Emanuela Fanelli e Francesco Riviera24 - 1 / 2 - 01.10.2021 2 Pannofino 12. Gaia – “Mi sono innamorato di te” (Luigi Tenco) con Lous And The Yakuza 13. Irama – “Cyrano” (Francesco Guccini) 14. Colapesce e Dimartino – “Povera patria” (Franco Battiato) 15. Fulminacci – “Penso positivo” (Jovanotti) con Valerio Lundini e Roy Paci 16. -

Saremo2021, Le Pagelle Della Terza Serata

1 Saremo2021, le pagelle della terza serata di Alice Spagnolo – 05 Marzo 2021 – 10:27 Sanremo. Pubblichiamo anche oggi la pagella della lunghissima terza serata del Festival di Sanremo. Una vera e propria prova di resistenza, visto che le serate finiscono sempre più tardi. Peccato, perché molti artisti meritavano di essere ascoltati. Negramaro. Nella serata delle cover, a 50 anni da quando nel 1971 il grande Lucio Dalla portò a Sanremo “4 marzo 1943”, sua data di nascita, i Negramaro regalano ai telespettatori un momento emozionante per celebrare la canzone d’autore, il compleanno del compianto Lucio, e la libertà della creazione di ogni artista. Giuliano Sangiorgi, il leader della band presenta un testo inedito sulla canzone d’autore, per poi intonare lo storico brano di Domenico Modugno, Meraviglioso, nella versione più rock della sua band. Sembrerà un gioco di parole, ma l’inizio della terza serata del Festival2021 è semplicemente MERAVIGLIOSO. Voto: 9 Noemi con Neffa. “Prima di andare via”. Alla coppia spetta il difficile compito di esibirsi dopo i Negramaro. E ci riescono pure piuttosto bene. Voto: 7 Fulminacci con Valerio Lundini e Roy Paci. “Penso positivo” di Jovanotti non è mai stata così “viva”, per parafrasarne il testo. Fantastici. Voto: 8 Vittoria Ceretti. La top model è sicuramente bellissima, ma se avesse smesso un attimo di dondolare sarebbe stato meglio. Voto: 5 Francesco Renga e Casadilego interpretano “Una ragione di più”. E non si capisce se prima l’avessero provata insieme o meno. Alza la media della performance il coraggio di Riviera24 - 1 / 3 - 29.09.2021 2 Casadilego che arriva sul palco vestita da fata-folletto con i suoi immancabili capelli turchini. -

I Måneskin Conquistano L'europa

RadiocorriereTv SETTIMANALE DELLA RAI RADIOTELEVISIONE ITALIANA numero 21 - anno 90 24 maggio 2021 Reg. Trib. n. 673 del 16 dicembre 1997 Il rock non morirà mai foto: NPO/NOS/AVROTROS NATHAN REINDS NATHAN foto: NPO/NOS/AVROTROS I Måneskin conquistano l’Europa Nelle librerie Nelle librerie e store digitali e store digitali 2 TV RADIOCORRIERE 3 SONO VACCINATO Nelle librerie Non vi nascondo che mentre mi recavo all’Outlet di Valmontone un pizzico di tensione si poteva scorgere sul e store digitali mio volto, ma una volta arrivato nell’area dedicata alla somministrazione dei vaccini mi sono potuto rendere conto di persona che se le cose si vogliono fare, si possono fare e bene. L’ennesima dimostrazione di un Paese che se ha voglia di funzionare, funziona. Una sanità pubblica che invece di perdersi in inutili chiacchiere si è messa a disposizione dei cittadini. Sarà per quella disperazione che ormai ci attanaglia dopo quindici mesi passati tra clausura, cautele e mascherine, ma arrivare ed essere accolti in modo a dir poco perfetto rende il tutto più semplice. Tutto facile, dalla registrazione alla somministrazione del vaccino. Un percorso che fai in auto, senza scendere, con l’infermiere che ti inietta l’adenovirus che innescherà la reazione degli anticorpi. Tornato a casa, dopo qualche ora, sono comparse alcune linee di febbre, un leggero mal di testa, e poi tutto è tornato come prima, nella consapevolezza di aver fatto la cosa giusta. Forse dovevano pensarci prima. È vero, mancavano i vaccini, ma anche quando c’erano si è perso del tempo in inutili quanto patetici progetti che da sempre ottengono come principale risultato quello di paralizzare la sanità del nostro Paese. -

Catalogo Completo Mp3 - 22/09/2021

M-LIVE CATALOGO COMPLETO MP3 - 22/09/2021 ZIBALDONE POPOLARE - ERAVAMO IN CENTOMILA RICOMINCIAMO ALEANDRO BALDI - ALEX BRITTI 2 VOL.2 FASCINO AEROSMITH FRANCESCA ALOTTA 7000 CAFFÈ FIORI 2 EIVISSA ABBA I DON'T WANT TO MISS A NON AMARMI BACIAMI E PORTAMI A CHIQUITITA FRESCO (LATIN THING BALLARE OH LA LA LA ALEJANDRO SANZ FT. DOES YOUR MOTHER REGGAETON) AFTERHOURS BENE COSÌ 24KGOLDN FT. IANN DIOR FUMO NEGLI OCCHI ZUCCHERO KNOW BIANCA BUONA FORTUNA MOOD UN ZOMBIE A LA FERNANDO (SMOKE GETS IN YOUR CINQUE PETALI DI ROSA AIELLO INTEMPERIE HONEY HONEY EYES) FORTUNA CHE NON ERA ORA 4 I HAVE A DREAM GELOSIA ALESSANDRA AMOROSO NIENTE VIENIMI A BALLARE 4 NON BLONDES KNOWING ME KNOWING GRAZIE PREGO SCUSI AMA CHI TI VUOL BENE L'ATTIMO PER SEMPRE HAI BUCATO LA MIA VITA AKA 7EVEN AMORE PURO WHAT'S UP YOU LA VASCA LOCA MONEY MONEY MONEY I PASSI CHE FACCIAMO ARRIVI TU LA VITA SOGNATA MI MANCHI TAKE A CHANCE ON ME IL FORESTIERO BELLEZZA INCANTO LO ZINGARO FELICE A MILLE PAROLE THE NAME OF THE GAME IL RAGAZZO DELLA VIA NOSTALGIA MILANO A-HA THE WINNER TAKES IT ALL GLUCK AL CORLEY BELLISSIMO OGGI SONO IO STAY ON THESE ROADS WATERLOO IL RAGAZZO DELLA VIA SQUARE ROOMS CIAO PERCHÈ TAKE ON ME ABBA - MERYL STREEP GLUCK (LIVE) AL JARREAU COMUNQUE ANDARE PIOVE IL TANGACCIO DIFENDIMI PER SEMPRE AA.VV. MAMMA MIA AFTER ALL QUANTO TI AMO IL TEMPO SE NE VA È ORA DI TE (FIND A WAY) 'O SOLE MIO SOS AL STEWART SE NON CI SEI IL TUO BACIO È COME UN È VERO CHE VUOI AUTUMN LEAVES (PIANO AC/DC YEAR OF THE CAT SENZA CHIEDERCI DI PIÙ JAZZ) ROCK RESTARE SOLO CON TE BACK IN BLACK