SAJAE 2009 Vol 38

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ramotshere Moiloa Local Municipality at a Glance

RAMOTSHERE MOILOA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY Integrated Development Plan 2020/2021 Table of Contents Mayor’s Foreword i Mayor Cllr.P K Mothoagae ............................................................................. Error! Bookmark not defined. Acting Municipal Manager’s Overview iv 1. CHAPTER 1: Executive Summary 1 1.1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Ramotshere Moiloa Local Municipality at a Glance ............................................................................ 1 1.3 The 2017-2022 IDP ............................................................................................................................. 2 1.4 The IDP Process ................................................................................................................................. 3 1.4.2 Phase 1 Analysis .......................................................................................................................................... 3 1.4.3 Phase 2: Strategies ...................................................................................................................................... 3 1.4.4 Phase 3: Projects ......................................................................................................................................... 4 1.4.5 Phase 4: Integration .................................................................................................................................... 5 -

Delareyville Main Seat of Tswaing Magisterial District

# # !C # # ### !C^ !.C# # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # # # # # ^ # # ^ # # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # !C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # #!C# # # # # # !C ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # !C # !C # #^ # # # # # # ## # #!C # # # # # # ## !C# # # # # # # !C# ## # # # # !C # !C # # # ## # # # ^ # # # # # # # # #!C# # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # # # ## #!C # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # ## # # ## # # # # # # !C # # # ## ## # ## # # # # !C # # # # ## # # !C# !C # #^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # #!C # ## # ##^ # !C #!C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # ## # # # !C# ## # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # ## # ## # # !C # # #!C # # # # # # # !C# # # # # !C # # # # !C## # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # ## ## ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # # ## # # #!C # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # ^ # # # ## # # # # # # # # # ## #!C # # # # # # # #!C # !C # # # # !C # #!C # # # # # # # # ## # # !C # ### # ## # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # ## # # # # # # !C # #### !C## # # # !C # # ## !C !C # # # # # # # # !.# # # # # # # ## # #!C# # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # ### # #^ # # # # # # # ## # # # # ^ # !C# ## # # # # # # !C## # # # # # # # ## # # # ## # !C ## # # # # # ## !C# # !C# ### # !C### # # ^ # # # !C ### # # # !C# ##!C # !C # # # ^ !C ## # # #!C ## # # # # # # # # # # ## !C## ## # # ## # ## # # # # # #!C # ## # # # # # # # ## # # !C # ^ # # ## # # # # # !.!C # # # # # # # !C # # !C# # ### # # # # # # # # # # ## !C # # # # ## !C -

Magistrates' Courts Act: Definition of Local Limits of Districts Created In

STAATSKOERANT, 31 OKTOBER 2014 No. 38170 3 GOVERNMENT NOTICE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT No. 861 31 October 2014 MAGISTRATES' COURTS ACT, 1944 (ACT NO. 32 OF 1944): DEFINITION OF LOCAL LIMITS OF DISTRICTS CREATED IN RESPECT OF THE GAUTENG AND NORTH WEST PROVINCES I,Tshililo Michael Masutha, Minister of Justice and Correctional Services, acting under section 2 1(a) of the Magistrates' Courts Act, 1944 (Act No. 32 of 1944), hereby, with effect from 1 December 2014, in respect of the magisterial districts created in terms of Government Notice No. 43 of 24 January 2014, define the local limits of each such district as indicated in Schedules 1 and 2 respectively. Any amendment to the name of the district, sub-district or place of sitting under this Notice shall be applicable to the place appointed for the holding of a court for each regional division and all seats mentioned in the Schedule to Government Notice No. 219 of 27 February 2004. Given under my hand at on this the4")-\day of 0100 Qe Two Thousand and Fourteen. TM MASUTHA, MP (ADV) MINISTER OF JUSTICE AND CORRECTIONAL SERVICES This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 4 Column Acreatedin CourtsColumnestablished B SCHEDULEfor 1: GAUTENG PROVINCEPoint-to-pointCo lum descriptions C No. 38170 2014 GAZETTE,31OCTOBER GOVERNMENT termsEkurhuleniNo.43Magisterial ofof 24 Central JanuaryGovernmentDistrict 2014GazettethePalm districts Ridge Startingproceed from in an the easterly intersection direction of the along N12 the Motorway N12 motorway, with the easternuntilit intersectsboundary ofwith Busoni the eastern Rock, This gazette isalsoavailable freeonline at boundary of Linmeyer Township. -

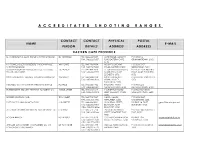

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

“Preview Copy Only”

TRANSNET FREIGHT RAIL a Division of TRANSNET SOC LIMITED (Registration No. 1990/000900/30) REQUEST FOR QUOTATION (“RFQ”) RFQ NUMBER CRAC- KGG-8786 SUPPLY AND DELIVERY OF SIGN BOARDS AT VARIOUS LEVEL CROSSING SITES (FROM KRUGERSDORP TO MAFIKENG). ISSUE DATE : 19 JUNE 2012 CLOSING DATE : 03 JULY 2012 CLOSING TIME : 10H00 A.M OPTION DATE : 30 OCTOBER 2012 CONTACT PERSON AARON MARINGA (083 689 5653) TENDER BOX ALLOCATED AT THE CHAIRPERSON TRANSNET FREIGHT RAIL ACQUISITION COUNCIL, GROUND FLOOR, INYANDA HOUSE 1, 21 WELLINGTON ROAD, PARKTOWN, JOHANNESBURG. Please note that late responses and those delivered or posted “PREVIEWto the wrong address COPY will be disqualified. ONLY” _____________________ ________________ Respondent’s signature 1 Date and company stamp RFQ NUMBER CRAC- KGG-8786 SUPPLY AND DELIVERY OF SIGN BOARDS AT VARIOUS LEVEL CROSSINGS. SCHEDULE OF DOCUMENTS 1. Notice to Bidders 2. Requisition for quotation 3. Scope of Work and General specification 4. Returnable Schedules / Documents 5. Supplier Declaration Form 6. General Tender Conditions (CSS5 – Services) 7. Standard Terms and Conditions of Contract (US7 - Services) 8. Non-Disclosure Agreement 9. Suppliers Code of Conduct “PREVIEW COPY ONLY” 2 _____________________ ________________ Respondent’s signature 2 Date and company stamp SECTION 1 RFQ NUMBER CRAC- KGG-8786 SUPPLY AND DELIVERY OF SIGN BOARDS AT VARIOUS LEVEL CROSSINGS. Quotations are requested from interested Respondents to supply the above-mentioned requirement to TRANSNET FREIGHT RAIL. On or after 19/06/2012 the RFQ documents may be inspected at, and are obtainable from the office of TRANSNET Freight Rail Tender Advice Centre, Inyanda 1, Ground Floor, 21 Wellington Road, and Parktown. -

Worldwide Soaring Turnpoint Exchange Unofficial

Worldwide Soaring Turnpoint Exchange Unofficial Coordinates for the Potchefstroom, South Africa Control Points Contest: South African Nationals, 2021 - 15m, 2 Seater and Club Class Courtesy of Oscar Goudriaan via Richard Glennie Dated: 20 September 2021 Magnetic Variation: 18.4W Printed Tuesday,21September 2021 at 13:44 GMT UNOFFICIAL, USE ATYOUR OWN RISK Do not use for navigation, for flight verification only. Always consult the relevant publications for current and correct information. This service is provided free of charge with no warrantees, expressed or implied. User assumes all risk of use. Number Name Latitude Longitude Latitude Longitude Elevation Codes* Comment Distance Bearing °’" °’" °’ °’ FEET Km 1Welkom 28 00 00 S 26 40 00 E 28 00.000 S 26 40.000 E 4528 AT153 214 2Control North 27 54 11 S 26 42 35 E 27 54.183 S 26 42.583 E 4528 T 141 213 3Control NW 27 54 42 S 26 36 00 E 27 54.700 S 26 36.000 E 4350 T Road Junction 146 217 4Welkom Start 27 59 46 S 26 32 41 E 27 59.767 S 26 32.683 E 4528 T 156 218 5Control South 28 06 32 S 26 42 58 E 28 06.533 S 26 42.967 E 4528 T 164 211 10 Riebeeckstad 27 54 58 S 26 47 35 E 27 54.967 S 26 47.583 E 4528 T 141 210 11 Odendaalsrus 27 51 10 S 26 44 06 E 27 51.167 S 26 44.100 E 4524 T 135 213 12 Virginia 28 07 44 S 26 53 36 E 28 07.733 S 26 53.600 E 4524 T 163 205 13 Allanridge 27 45 18 S 26 39 18 E 27 45.300 S 26 39.300 E 4528 T 127 218 14 Beatrix 28 14 01 S 26 46 01 E 28 14.017 S 26 46.017 E 4524 T 176 208 15 Welgelee 28 12 40 S 26 49 10 E 28 12.667 S 26 49.167 E 4524 T 173 207 16 Kalkvlakte -

37787 4-7 Roadcarrierp

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA July Vol. 589 Pretoria, 4 2014 Julie No. 37787 PART 1 OF 3 N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 402520—A 37787—1 2 No. 37787 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 4 JULY 2014 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the sender’s respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. CONTENTS INHOUD Page Gazette Bladsy Koerant No. No. No. No. No. No. Transport, Department of Vervoer, Departement van Cross Border Road Transport Agency: Oorgrenspadvervoeragentskap aansoek- Applications for permits:.......................... permitte: .................................................. Menlyn..................................................... 3 37787 Menlyn..................................................... 3 37787 Applications concerning Operating Aansoeke aangaande -

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC of SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA October Vol. 592 Pretoria, 31 Oktober 2014 No. 38170 N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 404749—A 38170—1 2 No. 38170 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 31 OCTOBER 2014 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the sender’s respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. CONTENTS • INHOUD Page Gazette No. No. No. GOVERNMENT NOTICE Justice and Constitutional Development, Department of Government Notice 861 Magistrate’s Courts Act (32/1944): Definition of local limits of districts created in respect of the Gauteng and North West Provinces .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 38170 This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za STAATSKOERANT, 31 OKTOBER 2014 No. 38170 3 GOVERNMENT NOTICE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT No. 861 31 October 2014 MAGISTRATES' COURTS ACT, 1944 (ACT NO. 32 OF 1944): DEFINITION OF LOCAL LIMITS OF DISTRICTS CREATED IN RESPECT OF THE GAUTENG AND NORTH WEST PROVINCES I,Tshililo Michael Masutha, Minister of Justice and Correctional Services, acting under section 2 1(a) of the Magistrates' Courts Act, 1944 (Act No. -

Proposed Main Seat / Sub District Within the Proposed Magisterial

# # !C # # ### ^ !.!C# #!C# # !C # # # # # # # # # ^!C# # # # # # # # ^ # # ^ # !C # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # !C # # # # # # ## # #!C # # # # # # #!C# # # # !C# ^ ## # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # #!C # # # # #!C^ # # # # # # ## # # #!C # # # # # # !C# # # # # # !C# # # # ## # # #!C # # #!C## # # # ^ # # # # # # ## # # # # # !C # # # # ## # # # # # # # ##!C # ## # # # # ## # # ## # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # ## ## # # #!C# # # # # !C # # # # ## # # ## # # # # !C# # # !C# # ^ # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## ## # !C #^# # !C #!C## ## # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # !C# ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # ## # ## # # # !C # #!C # # # # # # ## # # # # !C# # # # # # #!C # # # # !C## # # # # # # # # ## # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # !C # ## ## # # ## # # # # # ## ## # # #!C # ## # # # ^ # # ^ # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # ## # #!C # # !C # # !C # # !C## #!C # # # # # # # # # ## # ## # # !C# # # ## # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ### !C### # # # # !C !C# # # # # !C# # # # # # #!C ## !C# # !.# # # # # # ## ## # # #!C# # # # # # # # # ## # # ## # ## ##^ ## # # # # # # ## ## # # # # ^ # !C# ## # # # # # # !C## ## # # # # # # ## # # # !C## ##!C# # # ## !C# # !C### # ^ # # # !C ### # # # !C# ##!C # # !C ## # # ^ !C # # # #!C# # # ## # # # # ## # # # # # ## # !C # # # # # #!C # # # ## ## # # # # # !C # # # ## # # # !C^## ## # ## ## # # # !C !.# # !C# # #### # # # # # ## # # # ## !C ## # # # # # ## !C # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # -

Map Marking Information for Welkom, South Africa Courtesy of Oscar Goudriaan Via Carol Clifford

Map marking information for Welkom, South Africa Courtesy of Oscar Goudriaan via Carol Clifford Latitude range: -30 34.1 to -24 48.5 Longitude range: 22 3.2 to 28 59.5 File created Friday,04December 2020 at 23:33 GMT UNOFFICIAL, USE ATYOUR OWN RISK Do not use for navigation, for flight verification only. Always consult the relevant publications for current and correct information. This service is provided free of charge with no warrantees, expressed or implied. User assumes all risk of use. WayPoint Latitude Longitude Distance Bearing Description 227 Gariep Dam 30 34.1 S 25 32.0 E 306 201 Airfield 233 Philipstown 30 26.6 S 24 28.9 E 345 217 To wnCentre 200 Springfontein 30 16.1 S 25 43.1 E 269 200 Rail Station 209 Philippolis 30 13.0 S 25 13.0 E 284 209 231 Petrusville 30 6.9 S2431.0 E 315 221 177 Trompsburg301.6 S 25 46.1 E 242 201 Rail Station 221 PixleyKaLeRoux 29 59.7 S 24 43.8 E 291 220 Damwall 162 Jagerfontein 29 46.0 S 25 23.0 E 233 212 201 Luckhoff2944.9 S 24 45.4 E 269 223 Road X 178 Kestel 29 42.3 S 28 12.4 E 242 142 RailwayStation 152 Kalkfontein 29 30.0 S 25 13.1 E 219 220 Damwall 157 Koffiefontein 29 24.7 S 25 0.7 E225 225 Rail Station 135 Brulfontein 29 7.0 S256.0 E 197 231 Road X 112 Petrusburg297.0 S 25 25.0 E 174 224 88 Westpoint 28 56.0 S 25 45.7 E 136 220 87 Clocolaan 28 55.0 S 27 35.1 E 136 139 74 Krugersdrift 28 52.9 S 25 57.4 E 120 215 Damwall 101 Ficksburg2849.5 S 27 54.5 E 152 127 Airfield Map marking information for Welkom, South Africa, page 2 WayPoint Latitude Longitude Distance Bearing Description 71 Monte Carlo -

Copy of Privately Owned Dams

Capacity No of dam Name of dam Town nearest Province (1000 m³) A211/40 ASH TAILINGS DAM NO.2 MODDERFONTEIN GT 80 A211/41 ASH TAILINGS DAM NO.5 MODDERFONTEIN GT 68 A211/42 KNOPJESLAAGTE DAM 3 VERWOERDBURG GT 142 A211/43 NORTH DAM KEMPTON PARK GT 245 A211/44 SOUTH DAM KEMPTON PARK GT 124 A211/45 MOOIPLAAS SLIK DAM ERASMIA PRETORIA GT 281 A211/46 OLIFANTSPRUIT-ONDERSTE DAM OLIFANTSFONTEIN GT 220 A211/47 OLIFANTSPRUIT-BOONSTE DAM OLIFANTSFONTEIN NW 450 A211/49 LEWIS VERWOERDBURG GT 69 A211/51 BRAKFONTEIN RESERVOIR CENTURION GT 423 A211/52 KLIPFONTEIN NO1 RESERVOIR KEMPTON PARK GT 199 A211/53 KLIPFONTEIN NO2 RESERVOIR KEMPTON PARK GT 259 A211/55 ZONKIZIZWE DAM JOHANNESBURG GT 150 A211/57 ESKOM CONVENTION CENTRE DAM JOHANNESBURG GT 80 A211/59 AALWYNE DAM BAPSFONTEIN GT 132 A211/60 RIETSPRUIT DAM CENTURION GT 51 A211/61 REHABILITATION DAM 1 BIRCHLEIGH NW 2857 A212/40 BRUMA LAKE DAM JOHANNESBURG GT 120 A212/54 JUKSKEI SLIMES DAM HALFWAY HOUSE GT 52 A212/55 KYNOCH KUNSMIS LTD GIPS AFVAL DAM KEMPTON PARK GT 3000 A212/56 MODDERFONTEIN FACTORY DAM NO. 1 EDENVALE GT 550 A212/57 MODDERFONTEIN FACTORY DAM NO.2 MODDERFONTEIN GT 28 A212/58 MODDERFONTEIN FACTORY DAM NO. 3 EDENVALE GT 290 A212/59 MODDERFONTEIN FACTORY DAM NO. 4 EDENVALE GT 571 A212/60 MODDERFONTEIN FACTORY DAM NO.5 MODDERFONTEIN GT 30 A212/65 DOORN RANDJIES DAM PRETORIA GT 102 A212/69 DARREN WOOD JOHANNESBURG GT 21 A212/70 ZEVENFONTEIN DAM 1 DAINFERN GT 72 A212/71 ZEVENFONTEIN DAM 2 DAIRNFERN GT 64 A212/72 ZEVENFONTEIN DAM 3 MiDRAND GT 58 A212/73 BCC DAM AT SECOND JOHANNESBURG GT 39 A212/74 DW6 LEOPARD DAM LANSERIA NW 180 A212/75 RIVERSANDS DAM DIEPSLOOT GT 62 A213/40 WEST RAND CONS. -

Evaluating Use of Satellite Imagery in Mapping Differences in Geological Fertility in the Mahikeng - Ramotshere Moiloa Local Municipalities Based on Vegetation Cover

1tlll ·WEST UNIVERS YUN IIIESITI YA. 00K . E-BOPl-t lRIMA fltOOIIOWE •UN flJERSIT IT MAFIIKE'NG CAMPUS EVALUATING USE OF SATELLITE IMAGERY IN MAPPING DIFFERENCES IN GEOLOGICAL FERTILITY IN THE MAHIKENG - RAMOTSHERE MOILOA LOCAL MUNICIPALITIES BASED ON VEGETATION COVER M0600714g111 -7 Tf'-· •"'Y r: 9 J\Fr~,: ·,, , ... - ·i·]' .~ ?r; Gil!.Lrs0 -- .. -· -- - ·- . ::: - - ACC.•1- ·,. : -H--• ~" '-' ·-. i ; ~: . ~ .. Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requ iremen ts for the degree of Master of Science in Geography by FLORA MAJUNIA MAKGALE Supervisor: PROF. C. MUNYATI February 2014 SOLEMN DECLARATION I, Flora Majunia Makgale, declare that this thesis which I hereby submit to the North West University as completion of the requirements set for the Master's degree in Geography is my own work and has not already been submitted to any university. Further, I declare that I have duly acknowledged all my sources of information. SIGNED: ajunia Makgale DATE: DEDICATION I dedicate this research to my dear God for the divine enablement upon the completion. It 's not by might nor by power, but by the Spirit of the living God. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge North West University, Mafikeng Campus, Department of Geography and Environmental Sciences by giving me the opportunity to pursue this research under its directive. Most importantly, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my Supervisor Prof C. Munyati who was willingly assisting and stewarding for long difficult hours both in the office and in the field to make this study a success. His remarkable mentoring and encouraging spirit will remain a permanent mark to this achievement.