2. Adivasi Land Rights and Dispossession

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Participation of Women in the Freedom Struggle During the Gandhian Era: a Comparative Study Between Odisha and Andhra Pradesh

Odisha Review August - 2013 Participation of Women in the Freedom Struggle during the Gandhian Era: A Comparative Study between Odisha and Andhra Pradesh A. Sobha Rani S.C. Padhy Participation of women in the freedom struggle Role of Odia women in the Freedom forms an important and interesting aspect of the Movement: The Non-Cooperation History of Modern India. It is of great significance Movement: because it brought mass participation for the Women were more enthusiastic and political independence of the country. On Gandhi’s active in the Non-Cooperation movement in call large number of women joined the National Odisha. During his visit to Odisha, Gandhiji Congress and acted upon the advice by attended a meeting at Binod Behari. It was participating in the Movement. Gandhi opined that attended by forty women. Gandhi made a direct women were most suited to fight with the new 1 appeal to Odia women to join in the Non- weapons of non-violence and truth. When we 2 go through the history of freedom movement we Cooperation Movement. His speech had so see that his faith in women was true. They lived much inspired the Odia women present there that up to his expectation by actively participating in in response to his appeal many of them had the Non-Cooperation Movement, Civil donated their golden ornaments to the Swaraj Disobedience Movement and the Quit India Fund for freedom struggle. It may be worthwhile Movement. to note that after the speech many Oriya women had decided to join the national movement. One In the present study the two states of of them was Ramadevi, the wife of Gopabandhu Odisha and Andhra Pradesh are taken into Choudhury. -

Syllabus HISTORY (UG Course) Admitted Batch 2008 - 2009

Syllabus HISTORY (UG Course) Admitted Batch 2008 - 2009 May 2008 A.P. State Council of Higher Education SUBJECT COMMITTEE 1. Prof. A Bobbili Coordinator Kakatiya University 2. Prof A. Satyanarayana Osmania University 3. Prof M. Krishna Kumari Andhra University 4. Prof K. Reddappa Sri Venkateswara University 5. Prof (Mrs) P Hymavathi Acharya Nagarjuna University 6. Prof P Ramalakshmi Acharya Nagarjuna University 7. Prof K. Krishna Naik Sri Krishnadevaraya University 8. Dr R. Prasada Reddy Silver Jubilee Govt. College Kurnool 9. Dr G Sambasiva Reddy Govt. Degree College, Badvel, Kadapa Dist. B.A. Course (Structure) First year: S.No. Subject Hrs per Week 1. English language including communication 6 skills 2. Second language 4 3. Core l-1 6 4. Core 2-1 6 5. Core 3-1 6 6. Foundation course 3 7. Computer Skills 2 Total 33 Second year: S.No. Subject Hrs per week 1. English language including communication 6 skills 2. Second language 4 3. Core 1-II 6 4. Core 2-II 6 5. Core 3-II 6 6. Environmental studies 4 7. Computer skills 2 Total 34 Third year: S.No. Subject Hrs per week 1. Core 1-III 5 2. Core 1 – IV 5 3. Core 2 – III 5 4. Core 2 – IV 5 5. Core 3-III 5 6. Core 3 – IV 5 7. Foundation course 3 Total 33 ANDHRA UNIVERSITY HISTORY SYLLABUS ADMITTED BATCH 2008-09 B.A. History New Curriculum Paper – I History and culture of Indian up to AD 1526 Paper Unit I: Influence of Geography on History – Survey of the Sources – pre-historic period Paleolithic. -

Implications of Cinema's Politics for the Study of Urban Spaces

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ZENODO REVIEW OF URBAN AFFAIRS Three-Town Revolution: Implications of Cinema’s Politics for the Study of Urban Spaces S V Srinivas The point of convergence between cinema and iscussions on the commons tend to stress the use value of constituents of the urban commons is the crowd and common pool resources (CPRs) and their management, and balancing access and subtractability (depletion, ex- everything that the crowd connotes at any given point D haustion) of the resources in question, whether they be natural or of time and in any discourse. Popular Telugu cinema is human made.1 For example, Ostrom (1990) offers various models replete with examples of the crowd and what cinema for “governing the commons”. Hess (2008: 3) notes that recent does with it. This phenomenon of constituting and literature on the “new commons”, human-made, technologically driven resources, is marked by the perception that “the commons naming social formations and the misrecognitions it is a movement” whose concern is “what is shared or should be gives rise to are most instructive in a discussion of the shared” through cooperation and collective action. In some urban commons. This paper analyses Eenadu, a 1982 sense, the commons is increasingly sought to be the new site of Telugu film that is centrally concerned with crowds, to good politics. Does cinema have any relevance to these dis- cussions, particularly given the growing assault on common illustrate how cinema brings the mass gathered before resources in cities? the screen face-to-face with a version of itself on the Over the past three decades, writings on cinema in India and screen, framing a new mode of political participation elsewhere have made a persuasive case of its social and political pivoted on the popular appeal of larger-than-life significance. -

State City Hospital Name Address Pin Code Phone K.M

STATE CITY HOSPITAL NAME ADDRESS PIN CODE PHONE K.M. Memorial Hospital And Research Center, Bye Pass Jharkhand Bokaro NEPHROPLUS DIALYSIS CENTER - BOKARO 827013 9234342627 Road, Bokaro, National Highway23, Chas D.No.29-14-45, Sri Guru Residency, Prakasam Road, Andhra Pradesh Achanta AMARAVATI EYE HOSPITAL 520002 0866-2437111 Suryaraopet, Pushpa Hotel Centre, Vijayawada Telangana Adilabad SRI SAI MATERNITY & GENERAL HOSPITAL Near Railway Gate, Gunj Road, Bhoktapur 504002 08732-230777 Uttar Pradesh Agra AMIT JAGGI MEMORIAL HOSPITAL Sector-1, Vibhav Nagar 282001 0562-2330600 Uttar Pradesh Agra UPADHYAY HOSPITAL Shaheed Nagar Crossing 282001 0562-2230344 Uttar Pradesh Agra RAVI HOSPITAL No.1/55, Delhi Gate 282002 0562-2521511 Uttar Pradesh Agra PUSHPANJALI HOSPTIAL & RESEARCH CENTRE Pushpanjali Palace, Delhi Gate 282002 0562-2527566 Uttar Pradesh Agra VOHRA NURSING HOME #4, Laxman Nagar, Kheria Road 282001 0562-2303221 Ashoka Plaza, 1St & 2Nd Floor, Jawahar Nagar, Nh – 2, Uttar Pradesh Agra CENTRE FOR SIGHT (AGRA) 282002 011-26513723 Bypass Road, Near Omax Srk Mall Uttar Pradesh Agra IIMT HOSPITAL & RESEARCH CENTRE Ganesh Nagar Lawyers Colony, Bye Pass Road 282005 9927818000 Uttar Pradesh Agra JEEVAN JYOTHI HOSPITAL & RESEARCH CENTER Sector-1, Awas Vikas, Bodla 282007 0562-2275030 Uttar Pradesh Agra DR.KAMLESH TANDON HOSPITALS & TEST TUBE BABY CENTRE 4/48, Lajpat Kunj, Agra 282002 0562-2525369 Uttar Pradesh Agra JAVITRI DEVI MEMORIAL HOSPITAL 51/10-J /19, West Arjun Nagar 282001 0562-2400069 Pushpanjali Hospital, 2Nd Floor, Pushpanjali Palace, -

Dictionary of Martyrs: India's Freedom Struggle

DICTIONARY OF MARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala ii Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 DICTIONARY OF MARTYRSMARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala General Editor Arvind P. Jamkhedkar Chairman, ICHR Executive Editor Rajaneesh Kumar Shukla Member Secretary, ICHR Research Consultant Amit Kumar Gupta Research and Editorial Team Ashfaque Ali Md. Naushad Ali Md. Shakeeb Athar Muhammad Niyas A. Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF IDNIA AND INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH iv Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH First Edition 2018 Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE Government of India and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH 35, Ferozeshah Road, New Delhi - 110 001 © ICHR & Ministry of Culture, GoI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 978-81-938176-1-2 Printed in India by MANAK PUBLICATIONS PVT. LTD B-7, Saraswati Complex, Subhash Chowk, Laxmi Nagar, New Delhi 110092 INDIA Phone: 22453894, 22042529 [email protected] State Co-ordinators and their Researchers Andhra Pradesh & Telangana Karnataka (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) V. Ramakrishna B. Surendra Rao S.K. Aruni Research Assistants Research Assistants V. Ramakrishna Reddy A.B. Vaggar I. Sudarshan Rao Ravindranath B.Venkataiah Tamil Nadu Kerala (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) N. -

Brief Industrial Profile of Kalahandi District

Contents S. No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 3 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 3 1.2 Topography 3 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 4 1.4 Forest 5 1.5 Administrative set up 5 2. District at a glance 6 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area in the District of Kalahandi 9 3. Industrial Scenario Of Kalahandi 10 3.1 Industry at a Glance 9 3.2 Year Wise Trend Of Units Registered 11 3.3 Details Of Existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan Units In The 10 District 3.4 Large Scale Industries / Public Sector undertakings 11 3.5 Major Exportable Item 12 3.6 Growth Trend 12 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 12 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 12 3.8.1 List of the units in Kalahandi & near by Area 11 3.8.2 Major Exportable Item 12 3.9 Service Enterprises 12 3.9.1 Potentials areas for service industry 13 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 13 4. Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 14 4.1 Detail Of Major Clusters 14 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 14 4.1.2 Service Sector 14 4.2 Details of Identified cluster 14 5. General issues raised by industry association during the course of 14 meeting 6 Steps to set up MSMEs 15 2 Brief Industrial Profile of Kalahandi District 1. General Characteristics of the District The present district of Kalahandi was in ancient times a part of South Kosala. It was a princely state. After independence of the country, merger of princely states took place on 1st January, 1948. -

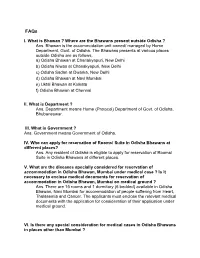

Ans. Bhawan Is the Accommodation Unit Owned/ Managed by Home Department, Govt

FAQs I. What is Bhawan ? Where are the Bhawans present outside Odisha ? Ans. Bhawan is the accommodation unit owned/ managed by Home Department, Govt. of Odisha. The Bhawans presents at various places outside Odisha are as follows, a) Odisha Bhawan at Chanakyapuri, New Delhi b) Odisha Niwas at Chanakyapuri, New Delhi c) Odisha Sadan at Dwarka, New Delhi d) Odisha Bhawan at Navi Mumbai e) Uktal Bhawan at Kolkata f) Odisha Bhawan at Chennai II. What is Department ? Ans. Department means Home (Protocol) Department of Govt. of Odisha, Bhubaneswar. III. What is Government ? Ans. Government means Government of Odisha. IV. Who can apply for reservation of Rooms/ Suite in Odisha Bhawans at different places? Ans. Any resident of Odisha is eligible to apply for reservation of Rooms/ Suite in Odisha Bhawans at different places. V. What are the diseases specially considered for reservation of accommodation in Odisha Bhawan, Mumbai under medical case ? Is it necessary to enclose medical documents for reservation of accommodation in Odisha Bhawan, Mumbai on medical ground ? Ans. There are 16 rooms and 1 dormitory (6 bedded) available in Odisha Bhawan, Navi Mumbai for accommodation of people suffering from Heart, Thalasemia and Cancer. The applicants must enclose the relevant medical documents with the application for consideration of their application under medical ground. VI. Is there any special consideration for medical cases in Odisha Bhawans in places other than Mumbai ? Ans. No. VII. When should I apply for reservation of accommodation in Bhawans ? Ans. The applications for reservation of accommodation in Bhawans must be sent with in 7 days but not later than 3 days of intended date of check in. -

Stamps of India - Commemorative by Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890

E-Book - 26. Checklist - Stamps of India - Commemorative By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 26. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 1st May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 76 Nos. YEAR PRICE NAME Mint FDC B. 1 2 3 1947 1 21-Nov-47 31/2a National Flag 2 15-Dec-47 11/2a Ashoka Lion Capital 3 15-Dec-47 12a Aircraft 1948 4 29-May-48 12a Air India International 5 15-Aug-48 11/2a Mahatma Gandhi 6 15-Aug-48 31/2a Mahatma Gandhi 7 15-Aug-48 12a Mahatma Gandhi 8 15-Aug-48 10r Mahatma Gandhi 1949 9 10-Oct-49 9 Pies 75th Anni. of Universal Postal Union 10 10-Oct-49 2a -do- 11 10-Oct-49 31/2a -do- 12 10-Oct-49 12a -do- 1950 13 26-Jan-50 2a Inauguration of Republic of India- Rejoicing crowds 14 26-Jan-50 31/2a Quill, Ink-well & Verse 15 26-Jan-50 4a Corn and plough 16 26-Jan-50 12a Charkha and cloth 1951 17 13-Jan-51 2a Geological Survey of India 18 04-Mar-51 2a First Asian Games 19 04-Mar-51 12a -do- 1952 20 01-Oct-52 9 Pies Saints and poets - Kabir 21 01-Oct-52 1a Saints and poets - Tulsidas 22 01-Oct-52 2a Saints and poets - MiraBai 23 01-Oct-52 4a Saints and poets - Surdas 24 01-Oct-52 41/2a Saints and poets - Mirza Galib 25 01-Oct-52 12a Saints and poets - Rabindranath Tagore 1953 26 16-Apr-53 2a Railway Centenary 27 02-Oct-53 2a Conquest of Everest 28 02-Oct-53 14a -do- 29 01-Nov-53 2a Telegraph Centenary 30 01-Nov-53 12a -do- 1954 31 01-Oct-54 1a Stamp Centenary - Runner, Camel and Bullock Cart 32 01-Oct-54 2a Stamp Centenary -

03 1. Why Did Gandhiji Organise Satyagraha in 1917 in Kheda District of Gujarat?

CLASS:-10TH, HISTORY, MCQ QUESTIONS ,CHAPTER:-03 NATIONALISM IN INDIA 1. Why did Gandhiji organise Satyagraha in 1917 in Kheda district of Gujarat? (a) To support the plantation workers (b) To protest against high revenue demand (c) To support the mill workers to fulfil their demand (d) To demand loans for the farmers Answer: b 2. Why was Satyagraha organised in Champaran in 1916? (a) To oppose the British laws (b) To oppose the plantation system (c) To oppose high land revenue (d) To protest against the oppression of the mill workers Answer:-b 2. Why was the Simon Commission sent to India? (a) To look into the Indian constitutional matter and suggest reform (b) To choose members of Indian Council (c) To settle disputes between the government and the Congress leaders (d) To set up a government organisation Answer: a 4. Why was Alluri Sitarama Raju well known? (a) He led the militant movement of tribal peasants in Andhra Pradesh. (b) He led a peasant movement in Avadh. (c) He led a satyagraha movement in Bardoli. (d) He set up an organisation for the uplifment of the dalits. Answer: a 5. Why did General Dyer open fire on peaceful crowd in Jallianwalla Bagh? Mark the most important factor. (a) To punish the Indians (b) To take revenge for breaking martial laws (c) To create a feeling of terror and awe in the mind of Indians (d) To disperse the crowd Answer: c 6. What kind of movement was launched by the tribal peasants of Gudem Hills in Andhra Pradesh? (a) Satyagraha Movement (b) Militant Guerrilla Movement (c) Non-Violent Movement (d) None of the above Answer: b 7. -

Director, Export Promotion & Marketing, Odisha, Raptani Bhawan, 1"T Floor, Near Lndradhanu Market, Nayapalli, Bhubaneswar-751015, Tel

MSME DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA DIRECTORATE OF EXPORT PROMOTION & MARKETING EXTENSION OF DATE FOR SUBMISSION OF APPLICATION FOR STATE EXPORT AWARD 2018.19 Applications are invited from the Exporters of Odisha for consideration of State Export Award for the year 2018-19. (1) Eligibility : All exporters of Odisha including Micro, Small, Medium and Large scale Enterprises, Export Houses, Merchant Exporters, Government of lndia undertakings based in Odisha as well as State Government undertakings are eligible to participate in the above competition furnishing the required information in the prescribed format in duplicate. (2) lnterested exporters are required to fill up the prescribed application form in all respect and submit to the Director, Export Promotion & Marketing, Odisha, Raptani Bhawan, 1"t Floor, Near lndradhanu Market, Nayapalli, Bhubaneswar-751015, Tel. No.0674-2552675, E-mail : [email protected] in duplicate. (3) The application form and State Export Award Scheme are available in the website www.odisha.gov.in / All Advertisement and "www.depmodisha.nic.in". (a) The application form can also be received from the office of the undersigned during the office hours on any working day. (5) The last date of deposit of applications for State Export Award 2018-19 is dt.31.12.2019. Application received after the due date shall not be entertained. Sd/- S.K. Jena, DIRECTOR, Export Promotion & Marketing, Odisha, Bhubaneswar GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA MSME DEPARTMENT >F ,r {< i< {< NOTIFICATION NO.II-MSME(DEPM)-125I13-350044SME, dated the 4th July, 2013. After creation of the separate Department of MSME and in supersession of Industries Department Notification No.4666l1, d1.09.03.1999, No.7801/1, dt.30.03.2001 and No.9939/1, dt.12.07 .2010 Government have been pleased to approve the revised State Export Award Scheme for the exporters of Odisha for their outstanding export performance in different product groups as mentioned in Para - 2 of this Scheme. -

District Statistical Hand Book-Subarnapur, 2011

GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA DISTRICT STATISTICAL HANDBOOK SUBARNAPUR 2011 DISTRICT PLANNING AND MONITORING UNIT SUBARNAPUR ( Price : Rs.25.00 ) CONTENTS Table No. SUBJECT PAGE ( 1 ) ( 2 ) ( 3 ) Socio-Economic Profile : Subarnapur … 1 Administrative set up … 4 I POSITION OF DISTRICT IN THE STATE 1.01 Geographical Area … 5 District wise Population with Rural & Urban and their proportion of 1.02 … 6 Odisha. District-wise SC & ST Population with percentage to total population of 1.03 … 8 Odisha. 1.04 Population by Sex, Density & Growth rate … 10 1.05 District wise sex ratio among all category, SC & ST by residence of Odisha. … 11 1.06 District wise Literacy rate, 2011 Census … 12 Child population in the age Group 0-6 in different district of Odisha. 1.07 … 13 II AREA AND POPULATION Geographical Area, Households and Number of Census Villages in different 2.01 … 14 Blocks and ULBs of the District. 2.02 Classification of workers (Main+ Marginal) … 15 2.03 Total workers and work participation by residence … 17 III CLIMATE 3.01 Month wise Actual Rainfall in different Rain gauge Stations in the District. … 18 3.02 Month wise Temperature and Relative Humidity of the district. … 20 IV AGRICULTURE 4.01 Block wise Land Utilisation pattern of the district. … 21 Season wise Estimated Area, Yield rate and Production of Paddy in 4.02 … 23 different Blocks and ULBs of the district. Estimated Area, Yield rate and Production of different Major crops in the 4.03 … 25 district. 4.04 Source- wise Irrigation Potential Created in different Blocks of the district … 26 Achievement of Pani Panchayat programme of different Blocks of the 4.05 … 27 district 4.06 Consumption of Chemical Fertiliser in different Blocks of the district. -

LOK SABHA ___ SYNOPSIS of DEBATES (Proceedings Other Than

LOK SABHA ___ SYNOPSIS OF DEBATES* (Proceedings other than Questions & Answers) ______ Friday, August 2, 2019 / Shravana 11, 1941 (Saka) ______ ANNOUNCEMENT BY THE SPEAKER Re: Emphasizing upon Janbhagidari on Food Nutrition Programme and involvement of Members in this regard. HON. SPEAKER: Our Prime Minister has taken a decision that all of us are obliged to associate ourselves with public participation to eradicate malnutrition from the country. This move will not only protect the mother from malnutrition but would ensure fairly healthy posterity. I urge upon all of you to create a mass movement on this count. _______ * Hon. Members may kindly let us know immediately the choice of language (Hindi or English) for obtaining Synopsis of Lok Sabha Debates. THE JALLIANWALA BAGH NATIONAL MEMORIAL (AMENDMENT) BILL, 2019 THE MINISTER OF STATE OF THE MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND MINISTER OF STATE OF THE MINISTRY OF TOURISM (SHRI PRAHLAD SINGH PATEL) moving the motion for consideration of the Bill, said: Jallianwala Bagh massacre took place on April 13, 1919. It occurs to me that Sadar Udham Singh was just five at that time and did harbour a kind of revolutionary flame in within which remained suppressed in his heart for a period of 21 years. Thereafter, he could not resist firing at General Dyre. Two days back was marked with death anniversary of martyr Udham Singh Ji and I pay tribute to him. This is the centenary year of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. I express my deep sense of gratitude and feel beholden to the Prime Minister of the country for rolling out a nation-wise celebration in the fond memory of the valiant heros of uprisings martyred in massacre.