Revision of the Inyo National Forest Land Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revised January 19, 2018 Updated June 19, 2018

BIOLOGICAL EVALUATION / BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT FOR TERRESTRIAL AND AQUATIC WILDLIFE YUBA PROJECT YUBA RIVER RANGER DISTRICT TAHOE NATIONAL FOREST REVISED JANUARY 19, 2018 UPDATED JUNE 19, 2018 PREPARED BY: MARILYN TIERNEY DISTRICT WILDLIFE BIOLOGIST 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... 3 II. INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................... 4 III. CONSULTATION TO DATE ...................................................................................................... 4 IV. CURRENT MANAGEMENT DIRECTION ............................................................................... 5 V. DESCRIPTION OF THE PROPOSED PROJECT AND ALTERNATIVES ......................... 6 VI. EXISTING ENVIRONMENT, EFFECTS OF THE PROPOSED ACTION AND ALTERNATIVES, AND DETERMINATION ......................................................................... 41 SPECIES-SPECIFIC ANALYSIS AND DETERMINATION ........................................................... 54 TERRESTRIAL SPECIES ........................................................................................................................ 55 WESTERN BUMBLE BEE ............................................................................................................. 55 BALD EAGLE ............................................................................................................................... -

Federal Register/Vol. 65, No. 233/Monday, December 4, 2000

Federal Register / Vol. 65, No. 233 / Monday, December 4, 2000 / Notices 75771 2 departures. No more than one slot DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION In notice document 00±29918 exemption time may be selected in any appearing in the issue of Wednesday, hour. In this round each carrier may Federal Aviation Administration November 22, 2000, under select one slot exemption time in each SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION, in the first RTCA Future Flight Data Collection hour without regard to whether a slot is column, in the fifteenth line, the date Committee available in that hour. the FAA will approve or disapprove the application, in whole or part, no later d. In the second and third rounds, Pursuant to section 10(a)(2) of the than should read ``March 15, 2001''. only carriers providing service to small Federal Advisory Committee Act (Pub. hub and nonhub airports may L. 92±463, 5 U.S.C., Appendix 2), notice FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: participate. Each carrier may select up is hereby given for the Future Flight Patrick Vaught, Program Manager, FAA/ to 2 slot exemption times, one arrival Data Collection Committee meeting to Airports District Office, 100 West Cross and one departure in each round. No be held January 11, 2000, starting at 9 Street, Suite B, Jackson, MS 39208± carrier may select more than 4 a.m. This meeting will be held at RTCA, 2307, 601±664±9885. exemption slot times in rounds 2 and 3. 1140 Connecticut Avenue, NW., Suite Issued in Jackson, Mississippi on 1020, Washington, DC, 20036. November 24, 2000. e. Beginning with the fourth round, The agenda will include: (1) Welcome all eligible carriers may participate. -

Rationales for Animal Species Considered for Species of Conservation Concern, Sequoia National Forest

Rationales for Animal Species Considered for Species of Conservation Concern Sequoia National Forest Prepared by: Wildlife Biologists and Biologist Planner Regional Office, Sequoia National Forest and Washington Office Enterprise Program For: Sequoia National Forest June 2019 In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. -

Publications Files/2011 Vila Et Al Beringia Supplmat.Pdf

Electronic supplementary material Phylogeny and paleoecology of Polyommatus blue butterflies show Beringia was a climate-regulated gateway to the New World Roger Vila, Charles D. Bell, Richard Macniven, Benjamin Goldman-Huertas, Richard H. Ree, Charles R. Marshall, Zsolt Bálint, Kurt Johnson, Dubi Benyamini, Naomi E. Pierce Contents Supplementary Methods. 2 Taxon sampling. 2 DNA extraction and sequencing . 2 Sequence alignments and characteristics. 3 Phylogenetic analyses. 4 Ancestral area reconstruction . 5 Ancestral hostplant reconstruction. 6 Ancestral temperature tolerance reconstruction . 6 Divergence time estimation . 7 Supplementary Results and Discussion. .8 Phylogenetic analyses. 8 Ancestral area reconstruction . 9 Ancestral hostplant reconstruction. 10 Ancestral temperature tolerance reconstruction . 10 Supplementary systematic discussion. 10 Interesting Nabokov citations. 13 List of Figures Supplementary Figure S1. Biogeographical model. 14 Supplementary Figure S2. Bayesian cladogram of the Polyommatini tribe. 15 Supplementary Figure S3. Polyommatini tribe node numbers. 16 Supplementary Figure S4. Polyommatus section node numbers . 17 Supplementary Figure S5. DIVA ancestral area reconstruction . 18 Supplementary Figure S6. Lagrange ancestral area reconstruction. 19 Supplementary Figure S7. Ancestral hostplant reconstruction . 20 Supplementary Figure S8. Ancestral and current thermal range tolerances. 21 List of Tables Supplementary Table S1. Samples used in this study . 22 Supplementary Table S2. Primer sequences . 25 Supplementary -

Preliminary Insect (Butterfly) Survey at Griffith Park, Los Angeles, California

Kathy Keane October 30, 2003 Keane Biological Consulting 5546 Parkcrest Street Long Beach, CA 90808 Subject: Preliminary Insect (Butterfly) Survey at Griffith Park, Los Angeles, California. Dear Kathy: Introduction At the request of Keane Biological Consulting (KBC), Guy P. Bruyea (GPB) conducted a reconnaissance-level survey for the butterfly and insect inhabitants of Griffith Park in northwestern Los Angeles County, California. This report presents findings of our survey conducted to assess butterfly and other insect diversity within Griffith Park, and briefly describes the vegetation, topography, and present land use throughout the survey area in an effort to assess the overall quality of the habitat currently present. Additionally, this report describes the butterfly species observed or detected, and identifies butterfly species with potential for occurrence that were not detected during the present survey. All observations were made by GPB during two visits to Griffith Park in June and July 2003. Site Description Griffith Park is generally located at the east end of the Santa Monica Mountains northwest of the City of Los Angeles within Los Angeles County, California. The ± 4100-acre Griffith Park is situated within extensive commercial and residential developments associated with the City of Los Angeles and surrounding areas, and is the largest municipal park and urban wilderness area within the United States. Specifically, Griffith Park is bounded as follows: to the east by the Golden State Freeway (Interstate Highway 5) and the -

One-Note Samba: the Biogeographical History of the Relict Brazilian Butterfly

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2015) ORIGINAL One-note samba: the biogeographical ARTICLE history of the relict Brazilian butterfly Elkalyce cogina Gerard Talavera1,2,3*, Lucas A. Kaminski1,4, Andre V. L. Freitas4 and Roger Vila1 1Institut de Biologia Evolutiva (CSIC- ABSTRACT Universitat Pompeu Fabra), 08003 Barcelona, Aim Biogeographically puzzling taxa represent an opportunity to understand Spain, 2Department of Organismic and the processes that have shaped current species distributions. The systematic Evolutionary Biology and Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, placement and biogeographical history of Elkalyce cogina, a small lycaenid but- Cambridge, MA 02138, USA, 3Faculty of terfly endemic to Brazil and neighbouring Argentina, are long-standing puzzles. Biology and Soil Science, St Petersburg State We use molecular tools and novel biogeographical and life history data to clar- University, 199034 St Petersburg, Russia, ify the taxonomy and distribution of this butterfly. 4 Departamento de Biologia Animal, Instituto Location South America, with emphasis on the Atlantic Rain Forest and Cer- de Biologia, Universidade Estadual de rado biomes (Brazil and Argentina). Campinas, 13083-970 Campinas, SP, Brazil Methods We gathered a data set of 71 Polyommatini (Lycaenidae) samples, including representatives of all described subtribes and/or sections. Among these, we contributed new sequences for E. cogina and four additional relevant taxa in the target subtribes Everina, Lycaenopsina and Polyommatina. We inferred a molecular phylogeny based on three mitochondrial genes and four nuclear markers to assess the systematic position and time of divergence of E. cogina. Ancestral geographical ranges were estimated with the R package BioGeoBEARS. To investigate heterogeneity in clade diversification rates, we used Bayesian analysis of macroevolutionary mixtures (bamm). -

Rationales for Animal Species Considered for Designation As Species of Conservation Concern Inyo National Forest

Rationales for Animal Species Considered for Designation as Species of Conservation Concern Inyo National Forest Prepared by: Wildlife Biologists and Natural Resources Specialist Regional Office, Inyo National Forest, and Washington Office Enterprise Program for: Inyo National Forest August 2018 1 In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. -

October 3, 2013 Minutes

MINUTES OF THE BOARD OF CHURCHILL COUNTY COMMISSIONERS 155 No. Taylor Street, Fallon, NV Fallon, Nevada October 3, 2013 CALL TO ORDER The regular meeting of the Churchill County Board of Commissioners was called to order at 8: 15 a.m. on the above date by Chairman Erquiaga. PRESENT: Carl Erquiaga, Chairman Pete Olsen, Vice-Chair Harry Scharmann, Commissioner Ben Shawcroft, Civil Deputy District Attorney Wade Carner, Civil Deputy District Attorney Eleanor Lockwood, County Manager Alan Kalt, Comptroller Kelly G. Helton, Clerk of the Board Pamela D. Moore, Deputy Clerk of the Board ABSENT: N/A PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE: The Pledge of Allegiance was recited by the board and public. VERIFICATION OF POSTING OF AGENDA: It was verified by Deputy Clerk Moore that the Agenda for this meeting was posted in accordance with NRS 241 . ACTION ITEMS: AGENDA: Commissioner Scharmann made a motion to approve the Agenda as submitted. Commissioner Olsen seconded the motion, which carried by unanimous vote. MINUTES: Commissioner Olsen made a motion to approve the Minutes of the special meeting held on September 26, 2011; the regular meeting held on September 5, 2013; and the regular meeting held on September 18, 2013 as submitted. Commissioner Scharmann seconded the motion, which carried by unanimous vote. PUBLIC COMMENTS : Chairman Erquiaga inquired if there were any public comments on issues that were not listed on the Agenda. Michelle Ippolito said she is here as President of the Fallon Animal Welfare Group. She had a prepared handout that explained more about what she is talking about today, which was distributed to the board and public and which included a brochure for the group. -

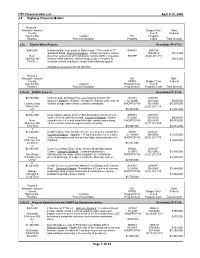

2.5 Highway Financial Matters

CTC Financial Vote List April 9-10, 2008 2.5 Highway Financial Matters Project # Allocation Amount Budget Year State County Item # Federal Dist-Co-Rte Location EA Program Postmile Project Description Program Codes Total Amount 2.5a. District Minor Projects Resolution FP-07-63 1 $943,000 In Bakersfield, from south of State Route 119 to north of 7th 0H4001 2007-08 Standard Road. Outcome/Outputs: Install microwave vehicle 302-0042 $943,000 Kern detection systems at 20 locations to monitor traffic congestion, SHOPP 20.20.201.315 06S-Ker-99 analyze traffic patterns, and develop computer models to $943,000 17.0/31.1 evaluate current and future needs of the highway system. (Substitute for project EA 06-0A5701) Project # Allocation Amount EA State County PPNO Budget Year Federal Dist-Co-Rte Location Program/Year Item # Postmile Project Description Prog Amount Program Code Total Amount 2.5b.(1) SHOPP Projects Resolution FP-07-64 1 $7,205,000 In Richmond, at Hilltop Drive overcrossing #28-0113R. 1A2501 2007-08 Outcome/Outputs: Replace 1 bridge to conform to the current 04-0248B 302-0042 $608,000 Contra Costa seismic design and vertical clearance standards. SHOPP/07-08 302-0890 $6,597,000 04N-CC-80 20.20.201.113 6.0 $8,800,000 $7,205,000 2 $6,082,000 Near Johannesburg, north of San Bernardino County line to 0E6901 2007-08 south of China Lake Boulevard. Outcome/Outputs: Widen 04-6266 302-0042 $609,000 Kern shoulders to 8 feet and install shoulder rumble strips along SHOPP/07-08 302-0890 $5,473,000 06S-Ker-395 14.5 centerline miles to improve motorist safety. -

Acceptance of Lotus Scoparius (Fabaceae) by Larvae of Lycaenidae

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 45(3). 1991. 188-196 ACCEPTANCE OF LOTUS SCOPARIUS (FABACEAE) BY LARVAE OF LYCAENIDAE GORDON F. PRATT Entomology and Applied Ecology Department, University of Delaware, Newark, Delaware 19716 AND GREGORY R. BALLMER Entomology Department, University of California, Riverside, California 92521 ABSTRACT. Larvae of 49 species of Lycaenidae were fed Lotus scoparius (Nutt. in T. & G.) Ottley (Fabaceae). Twentyseven species grew normally and pupated; six others fed but exhibited retarded development. Sixteen species refused to feed, or fed but exhibited no growth. Fourteen of the species reared to adults on L. scoparius are not known to use food plants in the Fabaceae in nature. Additional key words: coevolution, food plant, host shift. The larvae of most butterfly genera feed specifically on either a single genus or family of plants (Ehrlich & Raven 1964, Ackery 1988). The host range of some genera of Lycaenidae is comparatively broad. For example, members of the genus Callophrys Billberg feed on a wide range of plants in the families Convolvulaceae, Crassulaceae, Cupres saceae, Ericaceae, Fabaceae, Agavaceae, Pinaceae, Polygonaceae, Rhamnaceae, Rosaceae, and Viscaceae (Powell 1968, Emmel & Emmel 1973, Scott 1986, Ballmer & Pratt 1989b). Some lycaenid species, such as Strymon melinus Hubner, are also extremely polyphagous, whereas others are monophagous or oligophagous. One of us (GFP) observed that Callophrys mcfarlandi (Ehrlich & Clench) which, in nature, is monophagous on Nolina texana var com pacta (Trel.) (Agavaceae), could be reared in the laboratory on Lotus scoparius with little or no retardation in development. This plasticity in larval feeding capacity could indicate a broader ancestral host range and might support the theory that ancestral butterflies fed on Fabaceae (Scott 1984). -

Vila Et Al 10 ESM 5

Electronic supplementary material Phylogeny and paleoecology of Polyommatus blue butterflies show Beringia was a climate-regulated gateway to the New World Roger Vila, Charles D. Bell, Richard Macniven, Benjamin Goldman-Huertas, Richard H. Ree, Charles R. Marshall, Zsolt Bálint, Kurt Johnson, Dubi Benyamini, Naomi E. Pierce Contents Supplementary Methods. 2 Taxon sampling. 2 DNA extraction and sequencing . 2 Sequence alignments and characteristics. 3 Phylogenetic analyses. 4 Ancestral area reconstruction . 5 Ancestral hostplant reconstruction. 6 Ancestral temperature tolerance reconstruction . 6 Divergence time estimation . 7 Supplementary Results and Discussion. .8 Phylogenetic analyses. 8 Ancestral area reconstruction . 9 Ancestral hostplant reconstruction. 10 Ancestral temperature tolerance reconstruction . 10 Supplementary systematic discussion. 10 Interesting Nabokov citations. 13 List of Figures Supplementary Figure S1. Biogeographical model. 14 Supplementary Figure S2. Bayesian cladogram of the Polyommatini tribe. 15 Supplementary Figure S3. Polyommatini tribe node numbers. 16 Supplementary Figure S4. Polyommatus section node numbers . 17 Supplementary Figure S5. DIVA ancestral area reconstruction . 18 Supplementary Figure S6. Lagrange ancestral area reconstruction. 19 Supplementary Figure S7. Ancestral hostplant reconstruction . 20 Supplementary Figure S8. Ancestral and current thermal range tolerances. 21 List of Tables Supplementary Table S1. Samples used in this study . 22 Supplementary Table S2. Primer sequences . 25 Supplementary -

The Systematics of Polyommatus Blue Butterflies (Lepi

Cladistics Cladistics (2012) 1–27 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2012.00421.x Establishing criteria for higher-level classification using molecular data: the systematics of Polyommatus blue butterflies (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae) Gerard Talaveraa,b, Vladimir A. Lukhtanovc,d, Naomi E. Piercee and Roger Vilaa,* aInstitut de Biologia Evolutiva (CSIC-UPF), Passeig Marı´tim de la Barceloneta, 37, 08003 Barcelona, Spain; bDepartament de Gene`tica i Microbiologia, Universitat Auto`noma de Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra (Barcelona), Spain; cDepartment of Karyosystematics, Zoological Institute of Russian Academy of Science, Universitetskaya nab. 1, 199034 St Petersburg, Russia; dDepartment of Entomology, St Petersburg State University, Universitetskaya nab. 7 ⁄ 9, 199034 St Petersburg, Russia; eDepartment of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, 26 Oxford Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA Accepted 11 June 2012 Abstract Most taxonomists agree on the need to adapt current classifications to recognize monophyletic units. However, delineations between higher taxonomic units can be based on the relative ages of different lineages and ⁄or the level of morphological differentiation. In this paper, we address these issues in considering the species-rich Polyommatus section, a group of butterflies whose taxonomy has been highly controversial. We propose a taxonomy-friendly, flexible temporal scheme for higher-level classification. Using molecular data from nine markers (6666 bp) for 104 representatives of the Polyommatus section, representing all but two of the 81 described genera ⁄ subgenera and five outgroups, we obtained a complete and well resolved phylogeny for this clade. We use this to revise the systematics of the Polyommatus blues, and to define criteria that best accommodate the described genera within a phylogenetic framework.