Indigenous Resurgence and Everyday Practices of Farming in Okinawa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Kahala Hotel & Resort Hosts First Ever Ramen At

NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 26, 2019 Media Contacts: Dara Lum Amy Higa The Kahala Hotel & Resort iQ 360 for Sun Noodle [email protected] [email protected] (808) 739-8854 (808) 386-6790 THE KAHALA HOTEL & RESORT HOSTS FIRST EVER RAMEN AT THE BEACH EVENT WITH SUN NOODLE HONOLULU – The Kahala Hotel & Resort has partnered with Sun Noodle to host Ramen at the Beach, a three-night culinary event featuring world-renowned Ramen restaurateur, Chef Shigetoshi Nakamura at the Plumeria Beach House. Nakamura will serve his specialties – Torigara Shoyu Ramen and Steak Mazemen – as part of the Seafood Buffet at the oceanfront restaurant on April 5 and 6 from 5:30 to 10 p.m. The Buffets featuring Chef Nakamura’s dishes are $68 for adults and $34 for children (ages 6-12). Plumeria Beach House will also serve A la Carte Lunch and Dinner Sets featuring Nakamura’s Torigara Shoyu Ramen or Steak Mazemen with a cold Mapo Tofu side dish starting Sunday, April 7 and ending with Lunch on Friday, April 12. The Lunch Set costs $27 for Ramen or $31 for Mazemen. The Dinner Set costs $37 for Ramen or $42 for Mazemen and includes a choice of Beer, Wine, Sake or Dessert. Nakamura will make his final appearance for a “Pop-Up” Dinner service on Sunday, April 7 from 5:30 to 9 p.m. Reservations are required and the Ramen & Mazemen quantities are limited. To make reservations, please call The Kahala’s Dining Reservations at (808) 739-8760. “We are excited to partner with Sun Noodle, a local business with a long history of attention to quality and care,” said Gerald Glennon, general manager of the Kahala Hotel & Resort. -

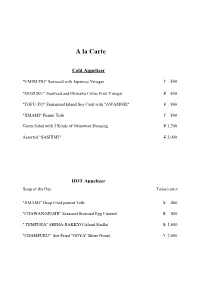

Muku Dinner Menu

A la Carte Cold Appetizer "UMIBUDO" Seaweed with Japanese Vinegar ¥ 800 "MOZUKU" Seaweed and Okinawa Citrus Fruit Vinegar ¥ 800 "TOFU-YO" Fermented Island Soy Curd with "AWAMORI" ¥ 800 "JIMAMI" Peanut Tofu ¥ 800 Green Salad with 3 Kinds of Okinawan Dressing ¥ 1,200 Assorted "SASHIMI" ¥ 3,000 HOT Appetizer Soup of the Day Today's price "JIMAMI" Deep Fried peanut Tofu ¥ 800 "CHAWAN-MUSHI" Seasonal Steamed Egg Custard ¥ 800 " TEMPURA" SHIMA-RAKKYO Island Shallot ¥ 1,000 "CHAMPURU" Stir-Fried "GOYA" Bitter Gourd ¥ 2,000 Chef's Special Dish ¥ 10,000 "Yakimono-Hassun" (Assorted small dishes) 11 kinds of Okinawan special small dishes on a big plate Grilled Ise Robster with butter Grilled Ishigaki beef Grilled Yambaru chicken with Ishigaki island salt Turban shell salad Deep-fried big-eye scad fish Tofu with oil bean paste and ishigaki beef Eel Sushi Shimeji mashrooms with soy sauce Jimami peanut Tofu Pickled roselle with sweet vinegar Various cracker Meat "YAMBARU-WAKADORI" Grilled Chicken with Teriyaki Sauce ¥ 2,500 "RAFTEA" Broil Stewed Cubes of Pork ¥ 3,000 "AGU SOKI ABURI" stewed pork spair ribs ¥ 3,500 Roasted Island "ISHIGAKI" Beef 80g ¥ 4,500 Roasted Island "ISHIGAKI" Beef 160g ¥ 9,000 "SHABU-SHABU SET" AGU Pork for two people ¥ 6,500 Extra AGU Pork 200g +¥2,500 Extra Okinawa Beef 200g +¥4,000 Seafood "TEMPURA" MOZUKU Seaweed ¥ 1,000 "GURUKUN KARAAGE" Deep-fried Black-tip fusilier fish Grilled Fish of the Day in butter ¥ 2,500 "TEMPURA" Island Shrimps and Vegetables ¥ 3,000 Rice & Noodles "JU-SHI" Okinawa Style Mixed Rice ¥ 800 Cold "ALOE" Udon Noodle ¥ 1,500 Hot Okinawa "SOBA" Noodles with "RAFTEA" ¥ 1,500 5 pieces of SUSHI ¥ 2,500 Dessert Ice Cream ¥ 500 Seasonal Dessert ¥ 800 Kid's Course ¥ 3,500 "DURUWAKASHI" Deep Fried TAIMO "SASHIMI" 2 Kinds of Islandfish "CHAWAN-MUSHI" Seasonal Egg Custard Grilled "AGU" Island Pork "JU-SHI" Okinawa Style Mixed Rice Dessert Kid's Plate ¥ 2,000 Humburg Steak / Fried Chicken Fried Shrimp / Fried Potato Salad Ice Cream. -

Ramen Kameya and Marugame Seimen Udon

totalokinawaTM www.totalokinawa.com October & November 2013 for 2 www.totalokinawa.com Totalokinawa Magazine October 2013 Magazine Totalokinawa totalokinawa CONTENTS OCTOBER & NOVEMBER In the Mood 2013 for Noodles Issue 18 The Noodle Issue ove over, fried rice. In our cover story, Mwe explore the beloved Japanese noodle, in its many forms and lavors. Plus, don’t miss our detailed reviews of noodle restaurants Ramen Kameya and Marugame Seimen Udon. Also, check out our review on www.totalokinawa.mobi the Okinawa YOHO honey store; you’ll “bee” Need a QR reader? craving a bottle or two for your own sweet stash. And, we’ve Check out our got our latest dive report and issue of Weird & Wonderful. magazine page on Also view the magazine online at: www.totalokinawa.com Totalokinawa.com 1 0 FEATURE IN THE MOOD FOR NOODLES Noodles p. 10 Okinawa YOHO Honey 4 Dive Report 6 Weird & Wonderful 9 In the Mood for Noodles 10 Ramen Kameya 13 Marugame Seimen Udon 17 Published in Okinawa by Totalokinawa.com by in Okinawa Published 2013. All Reserved Rights Copyright is All content - www.totalokinawa.com information advertising For the for responsible not partners are it’s and Totalokinawa external advertising. any of content 3 Totalokinawa Magazine October 2013 to Local Shop Review by Melissa Nazario YOHO Okinawa YOHO-ho! And a bottle of honey--Local shop ofers sweet selections. umans’ use of honey for medicinal reasons dates back thousands Hof years. Egyptians used it to dress wounds and embalm bodies. Today, there are lots of claims that honey can do much more, from talokinawa.com preventing diseases to being a “better” sugar for diabetics (it’s not—it to packs more calories and carbs and has the same efect as table sugar). -

2011 Okinawan Festival Chair's Message

www.huoa.org July/August 2011 Issue #133 Circulation 11,000 2011 Okinawan Festival Chair’s Message By Cyrus Tamashiro watchiya Masaasandoo! Great officers of the Okinawa Hawaii entertainment! Excitement! Kyokai. Entertainment will also K Pageantry! The months of feature the top Okinawan music, planning and anticipation will bear dance and taiko groups from Oahu, fruit on September 3 and 4, when the Maui and the Big Island. inspired members of clubs that comprise Be sure to visit Heiwa Dori, named the Hawaii United Okinawa Association after the famous marketplace in will present the 29th Okinawan Festival Naha, to pick up imported food at Kapiolani Park. products. Machiya-Gwa (Country At the first meeting of the 2011 Store) will carry new items including Okinawan Festival Committee, club sweet potato lavosh, green tea representatives were asked to come up with suggestions for our pretzels, yudofu and tsukemono. annual event. Brainstorming resulted in great ideas, including Hanagi Machiya-Gwa will be some that we are happy to introduce at this year’s Festival. Norman stocked with plants to purchase and Nakasone and Geno Oshiro independently came up with Taco take home. Stop in at the bustling Rice, a dish invented in Okinawa, which combines the main Ti Jukuishina-Mishimun tent where ingredients of the Tex-Mex taco, but layered on a bed of rice. Taco Rice is served in artisans and crafters will present their designs. Don’t forget to buy an Okinawan izakaya, independent restaurants, and fast food chains throughout Okinawa, and in Festival T-shirt at the T-shirt tent! Buy an exciting new cookbook in the Capital certain areas of mainland Japan. -

Make It a Date at SAM's!

A Taste of 8-page pullout Okinawa The 3 ‘R’s to good eating – Restaurants, Reviews & Recipes Make it a date at SAM’S! Satisfy your seafood and steak cravings at Sam’s by the Sea, the popular restaurant with a nautical- themed interior and exotic Hawaiian and Polynesian décor that was elected “Best Date Night Restaurant” in Stripes Best of the Pacific 2019. Take in the view of the ocean as you and someone special enjoy a tasty full- course dinner by candlelight. Delight your taste buds with our fresh lobster, King Crab, prawns, red snapper, mahi mahi, swordfish and oysters. And our top-quality juicy steaks will leave your mouth watering and your stomach satisfied. Our friendly staff promises to make it a memorable dinner. STRIPES OKINAWA E OF OK DECEMBER 12 – DECEMBER 25, 2019 AST INAW A T 2 A Try Kadena’s newest star – Seaside Restaurant One of the hidden gems of Kadena Air Base is the Seaside Restaurant. Recently renovated to offer a comfortable atmosphere and accompanied by a delicious new menu, the old Ristorante is GONE! The newest star of the menu is a 20-ounce Tennessee whiskey-glazed pork chop, which is cooked over an open flame grill and then topped with the succulent glaze. The fire perfectly chars the exterior, giving it classic grill marks and caramelized edges. This treat is sure to hit the spot for even the most discerning palate. Come taste it for yourself, we are sure you will agree! Gen a real gem on Okinawa Offering authentic Japanese and Okinawan cuisine at a reasonable price, Gen was recognized in Stripes’ Best of the Pacific 2013 as the best restaurant to expe- rience the local culture on Okinawa. -

Closed Thursday T E L 0980-47-2449

Closed Thursday T E L 0980-47-2449 ~~ SSoobbaa ~~ Gristle sparerib soba Medium \680 Large \750 The broth is made using Yanbaru pork called “Aguu” that are grown in Yanbaru, the northern part of Okinawa Popular soba with tender, boiled gristle spareribs on top!! Broiled gristle sparerib soba Medium \730 Large \800 Broth made using Yanbaru pork “Aguu”. Broiled gristle spareribs on top for added flavor! Okinawa Soba Medium \680 Large \750 Broth made using Yanbaru pork “Aguu”. Standard Okinawa soba with sliced pork belly and “kamaboko” fish cake on top!! Motobu Soba Medium \680 Large \750 Broth made using Yanbaru pork “Aguu”. Our signature soba with sliced pork belly, gristle spareribs and “kamaboko” fish cake on top!! Yushi Dofu(soft tohu)Soba ※limited availability \680 Broth made using Yanbaru pork “Aguu”. Soft tofu (yushi dofu) on top of soba noodles. Good match, broth and tohu. Plain Okinawa Soba \450 Simple Okinawa soba without pork; just chopped green onion and pickled ginger. Juicee ・ ・ ・ ・ ・ ・ ・ ・ \250 Okinawan mixed rice. Truly delicious!! Kuzukuzu meat on rice \250 Rice topped with pork belly and gristle sparerib flavored minced meat with plenty of sauce! ~~ KKiiddss’’mmeennuu ~~ Kids’Soba ・ ・ ・ ・ ・ ・ ¥450 Kids’Curry ・ ・ ・ ・ ・ ・ ¥450 ~~ SSeett mmeennuu ~~ Fried chicken set \800 (Chicken only ¥600) Standard popular fried chicken Pieces of marinated chicken; crispy outside and juicy inside! Okinawa pork loin cutlet set \1200 (Cutlet only ¥1000) Delicious pork loin cutlet. Brand pork grown in Yanbaru, surrounded with plenty of nature, and called Yanbaru pork. ~~ BBeesstt ddeeaall sseett mmeennuuss ~~ Fried chicken & Okinawa soba set ¥980 Okinawa pork loin cutlet & Okinawa soba set ¥1380 ~~ CCuurrrryy RRiiccee ~~ (including salad) Curry Rice ・ ・ ・ ・ \750 Curry with cutlet ・ \850 ~~ BBoowwll mmeennuu ~~ Sanso Don ・ ・ ・ ・ ・ ・ \850 Bowl of rice topped with sliced of pork belly and gristle spareribs. -

View the Full Menu

Donburi Chicken Curry 12.50 Japanese curry with chicken Chicken Teriyaki Donburi 10.50 Gyu Donburi 12.50 Sukiyaki beef clear noodles with soft boiled eggs and mixed veggies Katsu Donburi 10.50 Lunch Bento Box Breaded pork cooked with onions and egg in light broth 11.00 Oyako Donburi 10.50 Choose any two dishes from below Chicken cooked with onions and egg in light broth Served with soup, salad and rice Shrimp & Veggie Tempura Donburi 10.50 (Excluding the noodles) *Spicy Salmon Donburi 12.50 Chopped salmon mixed with sesame seed oil and Japanese pepper Sushi Bar *Tataki Donburi 12.50 3 PC Sushi 3PC Sashimi Chopped tuna mixed with sesame seed oil and Japanese pepper 6PC Calif Roll 6PC Cucumber Roll *Tekka Donburi 18.50 6PC Tuna Roll (extra $1.50 for spicy tuna) Medley of fresh tuna on a bed of sushi rice Unagi Donburi 19.50 Kitchen BBQ Eel with Teriyaki sauce Chicken Teriyaki Tonkatsu Oyako Don Katsu Don Entrees Okinawa Soba Miso Ramen Lunch Dinner Shoyu Ramen Kyushu Ramen Traditional Tempura Sansai or Tempura with Soba/Udon Shrimp & Veggie Tempura 10.50 13.50 Shrimp & Veggie Tempura Vegetable Tempura 8.50 9.50 Seafood Tempura 18.50 18.50 Super Lunch Teriyaki Grilled to perfection with our original homemade sauce 14.00 Chicken Teriyaki 10.50 11.95 Includes all dishes below Salmon Filet 15.50 15.50 Served with soup, salad and rice fn New York Steak 15.50 15.50 Sushi Bar Tonkatsu 12.95 6PC California Roll Deep fried crispy pork cutlet served with tonkatsu sauce Kitchen * Chirashi Deluxe 23.50 Chef’s selection of today’s best sashimi arranged -

OKINAWAN FESTIVALS GALORE!!! Summer 2002 Will Be Remembered As the Okinawan Festivals: the Hawaii United Okinawa the Last Two Decades

Uchinanchu The Voice of the Hawaii United Okinawa Association August/SeptemberU 2002 Issue #88 Circulation 10,200 OKINAWAN FESTIVALS GALORE!!! Summer 2002 will be remembered as the Okinawan festivals: the Hawaii United Okinawa the last two decades. “Summer of the Okinawan Festivals.” Association’s festival in Honolulu, a Labor Day A lively bon dance featuring both Okinawan and From Hilo’s wet and wild Haari Boat Festival at weekend tradition since 1982. For 20 years now, mainland Japan dance styles will close the Festival Wailoa State Park, to Maui‘s wowee of a festival HUOA members have pulled together to share on Saturday. The bon dance, which promises to be at the Rinzai Zen Mission in P¯a‘ia, to Oahu’s their culture with residents and visitors alike. one of the season’s biggest and best, will begin at celebration marking two decades of Okinawan (Uchinanchu takes a look back at the first 6 p.m. and wrap up at 9. If you plan to participate Festivals—and don’t forget Kaua‘i, which held its Okinawan Festival in 1982 on page 10.) Previous in the bon dance, keep in mind that the last shut- Okinawan Dance Festival earlier in the year— festivals have attracted more than 50,000 people tle bus bound for Kapi‘olani Community College there’s no question about it: the Uchinanchu spirit during its two-day run. will leave the park at 9:30 p.m. is alive and well in Hawai‘i! As in previous years, Festival-goers can avoid “Spirit of Okinawa” was the theme of the Maui the anticipated traffic congestion around Okinawa Kenjin Kai’s (MOKK) second annual Kapi‘olani Park by parking free of charge at Okinawan Festival, which was held Aug. -

Japan's Tasty Secrets

Japan's tasty secrets Local food that satisfies the world's most demanding eaters Think you've already tried the best that Japan has to offer? It appreciation of Japanese ingredients and their applications. might be time to think again. And one or two delicacies may strike you as extreme cuisine: enjoyable only by those whose palate is completely attuned to Japan is packed with delicious dishes. All over the country the full range of tastes and textures found in Japan, surely the people are constantly cooking up new ways to satisfy a nation's world's most diverse culinary culture. hunger for culinary perfection. Hundreds of gourmet treats come and go, some starting out as a local favorite and then That easy-to-extreme diversity is evident even in our initial sweeping the land. Occasionally a food fad will last, or maybe selection of local cuisines loved all over Japan—but you the nation grows to love a local delicacy over a period of years. probably won't have to read long before something gets your The greatest success stories are rewarded with a place in the mouth watering. Our second selection focuses on food that nation's heart. has won a loyal local following in the region where it originated. Here, too, you will find many dishes that can be— While various dishes are popular for showcasing local ingredi- or already are—cherished across regional or national boundar- ents, many others succeed for the most basic reason of all: they ies. And even if occasionally you catch yourself thinking, "I'm taste great! And once a local food becomes established at the not sure I could eat that," remind yourself that each dish is a national level, it's made it. -

Soba À La Okinawa You’Ve Never Had Noodles Like This Before

A Taste of Okinawa The 3 ‘R’s to good eating – Restaurants, Reviews & Recipes 4-page pullout STRIPES OKINAWA E OF OK AUGUST 20 – SEPTEMBER 2, 2020 AST INAW A T 2 A Your new favorite lunchtime go-to! Fore Fathers Food Truck serves up perfectly cooked specialty burgers, hearty hotdogs, and mouth-watering BBQ. Indulge in your midday cravings with any one of the delicious burgers on the vast menu. Or, bring your friends and chow down on all your other BBQ grill favorites like the tender pulled pork sandwich! Locations change daily so make sure to follow @forefathersfoodtruck on Facebook. Visit during lunch hours Monday – Friday or look for them at events across Kadena Air Base and Okinawa. One bite and you’ll know you found your new go-to for the best lunch on the island! Taste the Hawaiian vibe at Hale Noa Café Owned by a chef in Hawaii, Hale Noa Café has been attracting a wide-range of foreign customers. With its Hawaiian vibe, Hale Noa serves up the some of the best of the 50th state’s favorite foods. We choose the fresh- est ingredients for the best taste made from scratch. Enjoy Macadamia Nut Pancakes, Hawaiian Bowl, Fresh Poke Bowl and more! Hale Noa’s fluffy French Toast with berries and crème brulee sauce is to die for! Afterwards, wash it all down with one of our healthy and home- made smoothies. Start your day with a superior break- fast at Hale Noa Café. AUGUST 20 – SEPTEMBER 2, 2020 E OF OK STRIPES OKINAWA AST INAW A T 3 A Soba à la Okinawa You’ve never had noodles like this before STRIPES OKINAWA n Japan, everybody loves noodles, and Okinawans are no different. -

The Okinawan Festival

www.huoa.org July/August 2015 Issue #157 Circulation 9,820 The Okinawan Festival: ‘Hawaii’s Best of 2015’! By Tom Yamamoto, 33rd Okinawan Festival Chair aisai! Come one, come all to the “best cultur- sanshin, eisa, koto, taiko, shishimai, and karate. We are delighted to have Radio Hal festival in town”! That’s absolutely Okinawa’s Miuta Taisho Grand Prix winner Ritsuko Shibahiki, Okinawa correct! The Hawaii United Okinawa Association Yui Buyo with their contemporary Okinawan Line dances, and Nakagusuku is extremely proud to host its 33rd Okinawan Gosamaru Daiko, an award-winning eisa group from Nakagusuku Village. Festival on September 5 and 6. Recently named Performing for the first time is the collaboration of three dynamiceisa by the Honolulu Star Advertiser’s Hawaii’s Best groups: Chinagu Eisa Hawaii, Tokyo’s Nankuru Eisa and members of Naha of 2015 as the “Best Cultural Festival in Hawaii,” Daiko, who bring flair and intensity to the stage! Returning to our festival this recognition would not have been possible is “Hizuki” who was with us two years ago. Updates and details on festival if not for the multitude of HUOA club mem- entertainment schedules can be found on the HUOA website at huoa.org. bers, various organizations and individuals Also, tune in to Radio KZOO during the “Kariyushi Hour” on Sundays at 5:30 p.m. who drive this two-day long event. The months for announcements and updates on the festival. of planning, weeklong set-up prior to the festival and breakdown after the Last month, we celebrated a sister-state relationship that has been flour- festival all go unseen to the many festival goers who come to enjoy the per- ishing for the past 30 years. -

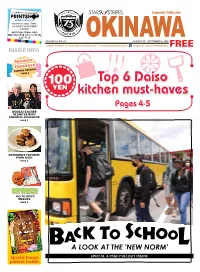

Okinawa Soba Is Some 3

Business cards, flyers, invitations and more! Contact printshop.stripes.com 042-552-2510 (extension77315) 227-7315 VOLUME 14 NO. 25 AUGUST 20 − SEPTEMBER 2, 2020 SUBMIT STORIES TO: [email protected] STRIPESOKINAWA.COM FACEBOOK.COM/STRIPESPACIFIC FREE INSIDE INFO Speakin’ Japanese SCHOOL SAYINGS PAGE 2 Top 6 Daiso kitchen must-haves Pages 4-5 DODEA TEACHER REUNITES WITH FAVORITE EDUCATOR PAGE 3 OKINAWA’S FAVORITE PORK DISH PAGE 6 GO-TO SPICY SNACKS PAGE 8 MY FAVES BACK TO SCHOOL A LOOK AT THE 'NEW NORM' Special 4-page SPECIAL 4-PAGE PULLOUT INSIDE pullout inside! 2 STRIPES OKINAWA A STARS AND STRIPES COMMUNITY PUBLICATION 75 YEARS IN THE PACIFIC AUGUST 20 − SEPTEMBER 2, 2020 Pronunciation key: “A” is short (like “ah”); “E” is short (like “get”); “I” is short (like “it”); “O” is long (like “old”); “U” is long (like “tube”); and “AI” is a long “I” (like “hike”). Most words are pro- nounced with equal emphasis on each syllable, but “OU” is a long Speakin’ “O” with emphasis on that syllable. Max D. Lederer Jr. Publisher Lt. Col. Richard E. McClintic Commander Joshua M Lashbrook Chief of Staff Japanese Chris Verigan Engagement Director “Isshoni gakko ni iki masho.” = Let’s go to the school Marie Woods School sayings Publishing and Media Design Director together. Once again our military children are back in school. And Japanese Chris Carlson (“isshoni” = together, “iki masho” = let’s go) Publishing and Media Design Manager kids are headed back after summer break (their school year begins “Chikoku shinai de kudasai.” = Please do not be late.