The Fall of Humanity (Genesis 2 and 3)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sin. Systematic Theology.Wayne Grudem

Systematic Theology Wayne Grudem Chapter 24! SIN What is sin? Where did it come from? Do we inherit a sinful nature from Adam? Do we inherit guilt from Adam? EXPLANATION AND SCRIPTURAL BASIS A. The Definition of Sin The history of the human race as presented in Scripture is primarily a history of man in a state of sin and rebellion against God and of God’s plan of redemption to bring man back to himself. Therefore, it is appropriate now to consider the nature of the sin that separates man from God. We may define sin as follows: Sin is any failure to conform to the moral law of God in act, attitude, or nature. Sin is here defined in relation to God and his moral law. Sin includes not only individual acts such as stealing or lying or committing murder, but also attitudes that are contrary to the attitudes God requires of us. We see this already in the Ten Commandments, which not only prohibit sinful actions but also wrong attitudes: “You shall not covet your neighbor’s house. You shall not covet your neighbor’s wife, or his manservant or maidservant, his ox or donkey, or anything that belongs to your neighbor” (Ex. 20:17 NIV). Here God specifies that a desire to steal or to commit adultery is also sin in his sight. The Sermon on the Mount also prohibits sinful attitudes such as anger (Matt. 5:22) or lust (Matt. 5:28). Paul lists attitudes such as jealousy, anger, and selfishness (Gal. 5:20) as things that are works of the flesh opposed to the desires of the Spirit (Gal. -

The Fall of Satan in the Thought of St. Ephrem and John Milton

Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies, Vol. 3.1, 3–27 © 2000 [2010] by Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Institute and Gorgias Press THE FALL OF SATAN IN THE THOUGHT OF ST. EPHREM AND JOHN MILTON GARY A. ANDERSON HARVARD DIVINITY SCHOOL CAMBRIDGE, MA USA ABSTRACT In the Life of Adam and Eve, Satan “the first-born” refused to venerate Adam, the “latter-born.” Later writers had difficulty with the tale because it granted Adam honors that were proper to Christ (Philippians 2:10, “at the name of Jesus, every knee should bend.”) The tale of Satan’s fall was then altered to reflect this Christological sensibility. Milton created a story of Christ’s elevation prior to the creation of man. Ephrem, on the other hand, moved the story to Holy Saturday. In Hades, Death acknowledged Christ as the true first- born whereas Satan rejected any such acclamation. [1] For some time I have pondered the problem of Satan’s fall in early Jewish and Christian sources. My point of origin has been the justly famous account found in the Life of Adam and Eve (hereafter: Life).1 1 See G. Anderson, “The Exaltation of Adam and the Fall of Satan,” Journal of Jewish Thought and Philosophy, 6 (1997): 105–34. 3 4 Gary A. Anderson I say justly famous because the Life itself existed in six versions- Greek, Latin, Armenian, Georgian, Slavonic, and Coptic (now extant only in fragments)-yet the tradition that the Life drew on is present in numerous other documents from Late Antiquity.2 And one should mention its surprising prominence in Islam-the story was told and retold some seven times in the Koran and was subsequently subject to further elaboration among Muslim exegetes and storytellers.3 My purpose in this essay is to carry forward work I have already done on this text to the figures of St. -

Beginnings Lesson Plans

Outline of Lessons WEEK #1—Introduction to God’s Word Sunday Overview of Timeline Study What We Expect Wednesday “Who’s Who? and What’s What?” God, The Bible, Satan and Man WEEK #2—“In the Beginning” Sunday “Let Us”—God and Creation “Where Are You?”—Man Sins Wednesday Prophecy of Christ—God Makes Atonement Brothers: Cain, Abel and Seth WEEK #3—God’s Judgment and Mercy Sunday The Ark—God’s Design The Flood—God’s Judgment The Deliverance—God’s Mercy Wednesday The Rainbow—God’s Covenant Noah’s Three Sons—Shem, Ham and Japheth Tower of Babel—God Scatters the People 1 Essential Knowledge Lesson 1a 1. SW become familiar with the TIMELINE UNIT of study: • 12 TIMELINE sections • BIBLE HISTORY HIGHWAY • TIMELINE TALK 2. SW know how to use their TIMELINE booklet and what is inside. 3. SW learn something about their teachers. 4. SW know what their personal and spiritual responsibilities are in studying the BIBLE TIMELINE. Lesson 1b 1. God is the author of the Bible, and that the Bible is perfect. 2. Satan is real and is the author of sin. 3. Man is free to choose his master. Lesson 2a 1. God had Others with Him during creation. 2. God was pleased with His creation. 3. God is Great and man is small. 4. Man cannot hide from God. 5. Man must choose whom he will obey. Lesson 2b 1. Christ was in existence before man. 2. All who sin suffer consequences and sin separates man from God. 3. Some offerings to God are not respected by God. -

HNA April 11 Cover-Final.Indd

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 28, No. 1 April 2011 Jacob Cats (1741-1799), Summer Landscape, pen and brown ink and wash, 270-359 mm. Hamburger Kunsthalle. Photo: Christoph Irrgang Exhibited in “Bruegel, Rembrandt & Co. Niederländische Zeichnungen 1450-1850”, June 17 – September 11, 2011, on the occasion of the publication of Annemarie Stefes, Niederländische Zeichnungen 1450-1850, Kupferstichkabinett der Hamburger Kunsthalle (see under New Titles) HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone/Fax: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President - Stephanie Dickey (2009–2013) Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art Queen’s University Kingston ON K7L 3N6 Canada Vice-President - Amy Golahny (2009–2013) Lycoming College Williamsport, PA 17701 Treasurer - Rebecca Brienen University of Miami Art & Art History Department PO Box 248106 Coral Gables FL 33124-2618 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Board Members Contents Dagmar Eichberger (2008–2012) HNA News ............................................................................1 Wayne Franits (2009–2013) Matt Kavaler (2008–2012) Personalia ............................................................................... 2 Henry Luttikhuizen (2009 and 2010–2014) Exhibitions -

Janson. History of Art. Chapter 16: The

16_CH16_P556-589.qxp 12/10/09 09:16 Page 556 16_CH16_P556-589.qxp 12/10/09 09:16 Page 557 CHAPTER 16 CHAPTER The High Renaissance in Italy, 1495 1520 OOKINGBACKATTHEARTISTSOFTHEFIFTEENTHCENTURY , THE artist and art historian Giorgio Vasari wrote in 1550, Truly great was the advancement conferred on the arts of architecture, painting, and L sculpture by those excellent masters. From Vasari s perspective, the earlier generation had provided the groundwork that enabled sixteenth-century artists to surpass the age of the ancients. Later artists and critics agreed Leonardo, Bramante, Michelangelo, Raphael, Giorgione, and with Vasari s judgment that the artists who worked in the decades Titian were all sought after in early sixteenth-century Italy, and just before and after 1500 attained a perfection in their art worthy the two who lived beyond 1520, Michelangelo and Titian, were of admiration and emulation. internationally celebrated during their lifetimes. This fame was For Vasari, the artists of this generation were paragons of their part of a wholesale change in the status of artists that had been profession. Following Vasari, artists and art teachers of subse- occurring gradually during the course of the fifteenth century and quent centuries have used the works of this 25-year period which gained strength with these artists. Despite the qualities of between 1495 and 1520, known as the High Renaissance, as a their births, or the differences in their styles and personalities, benchmark against which to measure their own. Yet the idea of a these artists were given the respect due to intellectuals and High Renaissance presupposes that it follows something humanists. -

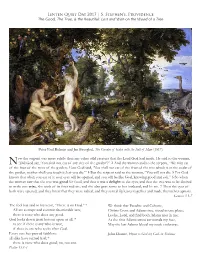

Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel, the Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man (1617)

Lenten Quiet Day 2017 | S. Stephen’s, Providence The Good, The True, & the Beautiful: Lost and Won on the Wood of a Tree Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel, The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man (1617) ow the serpent was more subtle than any other wild creature that the Lord God had made. He said to the woman, N“Did God say, ‘You shall not eat of any tree of the garden’?” 2 And the woman said to the serpent, “We may eat of the fruit of the trees of the garden; 3 but God said, ‘You shall not eat of the fruit of the tree which is in the midst of the garden, neither shall you touch it, lest you die.’” 4 But the serpent said to the woman, “You will not die. 5 For God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.” 6 So when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate; and she also gave some to her husband, and he ate. 7 Then the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together and made themselves aprons. Genesis 3.1-7 The fool has said in his heart, “There is no God.” * We think that Paradise and Calvarie, All are corrupt and commit abominable acts; Christs Cross and Adams tree, stood in one place; there is none who does any good. -

Ribera's Drunken Silenusand Saint Jerome

99 NAPLES IN FLESH AND BONES: RIBERA’S DRUNKEN SILENUS AND SAINT JEROME Edward Payne Abstract Jusepe de Ribera did not begin to sign his paintings consistently until 1626, the year in which he executed two monumental works: the Drunken Silenus and Saint Jerome and the Angel of Judgement (Museo di Capodimonte, Naples). Both paintings include elaborate Latin inscriptions stating that they were executed in Naples, the city in which the artist had resided for the past decade and where he ultimately remained for the rest of his life. Taking each in turn, this essay explores the nature and implications of these inscriptions, and offers new interpretations of the paintings. I argue that these complex representations of mythological and religious subjects – that were destined, respectively, for a private collection and a Neapolitan church – may be read as incarnations of the city of Naples. Naming the paintings’ place of production and the artist’s city of residence in the signature formulae was thus not coincidental or marginal, but rather indicative of Ribera inscribing himself textually, pictorially and corporeally in the fabric of the city. Keywords: allegory, inscription, Naples, realism, Jusepe de Ribera, Saint Jerome, satire, senses, Silenus Full text: http://openartsjournal.org/issue-6/article-5 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5456/issn.2050-3679/2018w05 Biographical note Edward Payne is Head Curator of Spanish Art at The Auckland Project and an Honorary Fellow at Durham University. He previously served as the inaugural Meadows/Mellon/Prado Curatorial Fellow at the Meadows Museum (2014–16) and as the Moore Curatorial Fellow in Drawings and Prints at the Morgan Library & Museum (2012–14). -

Transcendence of God

TRANSCENDENCE OF GOD A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE OLD TESTAMENT AND THE QUR’AN BY STEPHEN MYONGSU KIM A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (PhD) IN BIBLICAL AND RELIGIOUS STUDIES IN THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA SUPERVISOR: PROF. DJ HUMAN CO-SUPERVISOR: PROF. PGJ MEIRING JUNE 2009 © University of Pretoria DEDICATION To my love, Miae our children Yein, Stephen, and David and the Peacemakers around the world. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I thank God for the opportunity and privilege to study the subject of divinity. Without acknowledging God’s grace, this study would be futile. I would like to thank my family for their outstanding tolerance of my late studies which takes away our family time. Without their support and kind endurance, I could not have completed this prolonged task. I am grateful to the staffs of University of Pretoria who have provided all the essential process of official matter. Without their kind help, my studies would have been difficult. Many thanks go to my fellow teachers in the Nairobi International School of Theology. I thank David and Sarah O’Brien for their painstaking proofreading of my thesis. Furthermore, I appreciate Dr Wayne Johnson and Dr Paul Mumo for their suggestions in my early stage of thesis writing. I also thank my students with whom I discussed and developed many insights of God’s relationship with mankind during the Hebrew Exegesis lectures. I also remember my former teachers from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, especially from the OT Department who have shaped my academic stand and inspired to pursue the subject of this thesis. -

June 23, 2006 for IMMEDIATE RELEASE PREMIERE PRESENTATION

DATE: Friday, June 23, 2006 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PREMIERE PRESENTATION EXHIBITION EXPLORES THE PROFESSIONAL EXCHANGES AND CLOSE FRIENDSHIP BETWEEN TWO GREAT 17th-CENTURY MASTERS Rubens and Brueghel: A Working Friendship At the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577-1640) and Jan Brueghel the Elder Center, July 5–September 24, 2006 (Flemish, 1568-1625) The Return from War: Mars Disarmed by Venus, about 1610–1612 Oil on panel 127.3 x 163.5 cm (50 1/8 x 64 3/8 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California, acquired in honor of John Walsh. 2000.68 LOS ANGELES—One of the greatest artistic partnerships in history—between Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) and Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568–1625)—will be explored in Rubens and Brueghel: A Working Friendship, at the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Center, July 5–September 24, 2006. This Premiere Presentation is the first major international loan exhibition devoted to the collaborative works of Rubens and Brueghel, and is one of the J. Paul Getty Museum’s most important shows of the year. It will feature the largest group of paintings by the two 17th-century masters ever seen together, examining their professional partnership, personal friendship, and unique collaborative process. Rubens and Brueghel: A Working Friendship has been organized by the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis. Following its showing at -more- Page 2 the Getty Center in Los Angeles, the exhibition will be presented at the Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands, from October 21, 2006–January 28, 2007. -

Mark Twain and the Bible

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Kentucky University of Kentucky UKnowledge American Literature American Studies 1969 Mark Twain and the Bible Allison Ensor University of Tennessee - Knoxville Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Ensor, Allison, "Mark Twain and the Bible" (1969). American Literature. 4. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_american_literature/4 Mark Twain & The Bible This page intentionally left blank MARK TWAIN & THE JBIJBLE Allison Ensor UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY PRESS Copyright (c) I 969 UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY PRESS, LEXINGTON Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 76-80092 Standard Book NU11lber 8131-1181-1 TO Anne & Beth This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgments THis BOOK could not have been what it is without the assistance of several persons whose help I gratefully acknowledge: Professor Edwin H. Cady, Indiana Uni versity, guided me through the preliminaries of this study; Professor Nathalia Wright, University of Ten nessee, whose study of Melville and the Bible is still a standard work, read my manuscript and made valuable suggestions; Professor Henry Nash Smith, University of California at Berkeley, former editor of the Mark Twain Papers, read an earlier version of the book and encouraged and directed me by his comments on it; the Graduate School of the University of Tennessee awarded me a summer grant, releasing me from teach ing responsibilities for a term so that I might revise the manuscript; and my wife, Anne Lovell Ensor, was will ing to accept Mark Twain as a member of the family for some five years. -

Dryden's the State of Innocence and Fall of Man, an Operatic Version of Paradise Lost

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2006 Forbidden Fruit: Dryden's The State of Innocence And Fall of Man, An Operatic Version of Paradise Lost Devane King Middleton Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Recommended Citation Middleton, Devane King, "Forbidden Fruit: Dryden's The State of Innocence And Fall of Man, An Operatic Version of Paradise Lost" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 167. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/167 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FORBIDDEN FRUIT: DRYDEN’S THE STATE OF INNOCENCE AND FALL OF MAN , AN OPERATIC VERSION OF PARADISE LOST by DEVANE KING MIDDLETON (Under the Direction of Candy B. K. Schille) ABSTRACT Ever since Dryden published his opera The State of Innocence , critics have speculated about his reasons for making a stage adaptation of Milton’s Paradise Lost . The fact that Dryden worked for Milton in Cromwell’s government may have been a factor. Dryden’s Puritan indoctrination during childhood, followed by influences from a royalist schoolmaster in his teenage years, makes the answer to the question somewhat more complex, as does the fact that the play, its source a Puritan epic adapted by an Anglican royalist poet, is dedicated to the Catholic bride of James, Duke of York and brother to Charles II. -

Using Scriptural Data to Calculate a Range-Qualified Chronology from Adam to Abraham

Using Scriptural Data to Calculate a Range-Qualified Chronology from Adam to Abraham With Comments on Why the "Open"-or-"Closed" Genealogy Question Is Chronometrically Irrelevant By: Thomas D. Ice, Th.M., Ph.D. Director, Pre-Trib Research Center Adjunct Professor, Tyndale Theological Seminary James J. Scofield Johnson, Th.D., D.C.Ed. Master Faculty, LeTourneau University Biblical Languages Instructor, Cross Timbers Institute Presented at the Southwest Regional Meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society at The Criswell College in Dallas, Texas on March 1, 2002. And God said, "Let there be lights in the firmament of the heaven to divide the day from the night; and let them be for signs, and for seasons, and for days, and for years...." (Genesis 1:14) I. Introductory Overview God intended that His human creatures would be able to use the sun to calculate time on Earth, in years.1 The regular amount of time used when the Earth orbits around the sun is called a "year."2 Because earthly sun-orbits recur on a regular3 basis (and that is reliable and true because God made it to be so), years are a reliable and true time-unit for quantifying time on the Earth.4 The physical universe exists in space, time, and matter-energy (the latter category being a more technical name for "stuff"). God made time "in the beginning," at the same time when He made space and matter-energy. God works in time, not because He must but because He wanted to. God made mankind to live, on Earth, inside time (and space and stuff).